The catboat is a beamy, monohulled sailboat descended from a line of working watercraft. No one is sure of the origin of the name “catboat.” Some said the boat was as fleet as a cat. Or, the name might have been inspired by dock cats that greeted returning fishermen. Catboats fished, hauled freight, and ferried passengers along the U.S. Eastern Seaboard as early as 1850. Their spiritual home is Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where generations of the Crosby family built catboats, determining their shapes with hand-carved models.

The beam of a catboat is typically half its length. Such generous beam afforded room for a fisherman to work. A single mast, stepped far forward, has a forestay but generally no shrouds. The rig is a single sail, often a gaffer. Fishermen made headroom by furling the rig then hiking it high overhead with one of the halyards. Because catboats worked in shallow waters, most have shoal draft and a centerboard. Catboats have a characteristic barn-door rudder, hung proud of the stern and steered with a tiller.

Working watermen eventually adopted steam and gasoline. But a new kind of sailor, the pleasure boater, adopted the catboat, which retains a loyal following to this day.

Naval architect Charles W. Wittholz of Silver Spring, Maryland, designed boats ranging from 11’ dinghies to 85′ replica ships. In his career, Wittholz designed several catboats, but it was the 17-footer that he himself sailed on the Potomac River. Built in 1967, he named his boat GOOD OMEN and sailed her for more than 20 years.

Monte Copeland

Monte CopelandThe keel version of the Wittholz 17 catboat has its greatest draft 13-1/2′ back from the stem, so it can be brought fairly close to shore. The bundled boom and gaff have been hiked up by the peak halyard to provide more headroom in the cockpit.

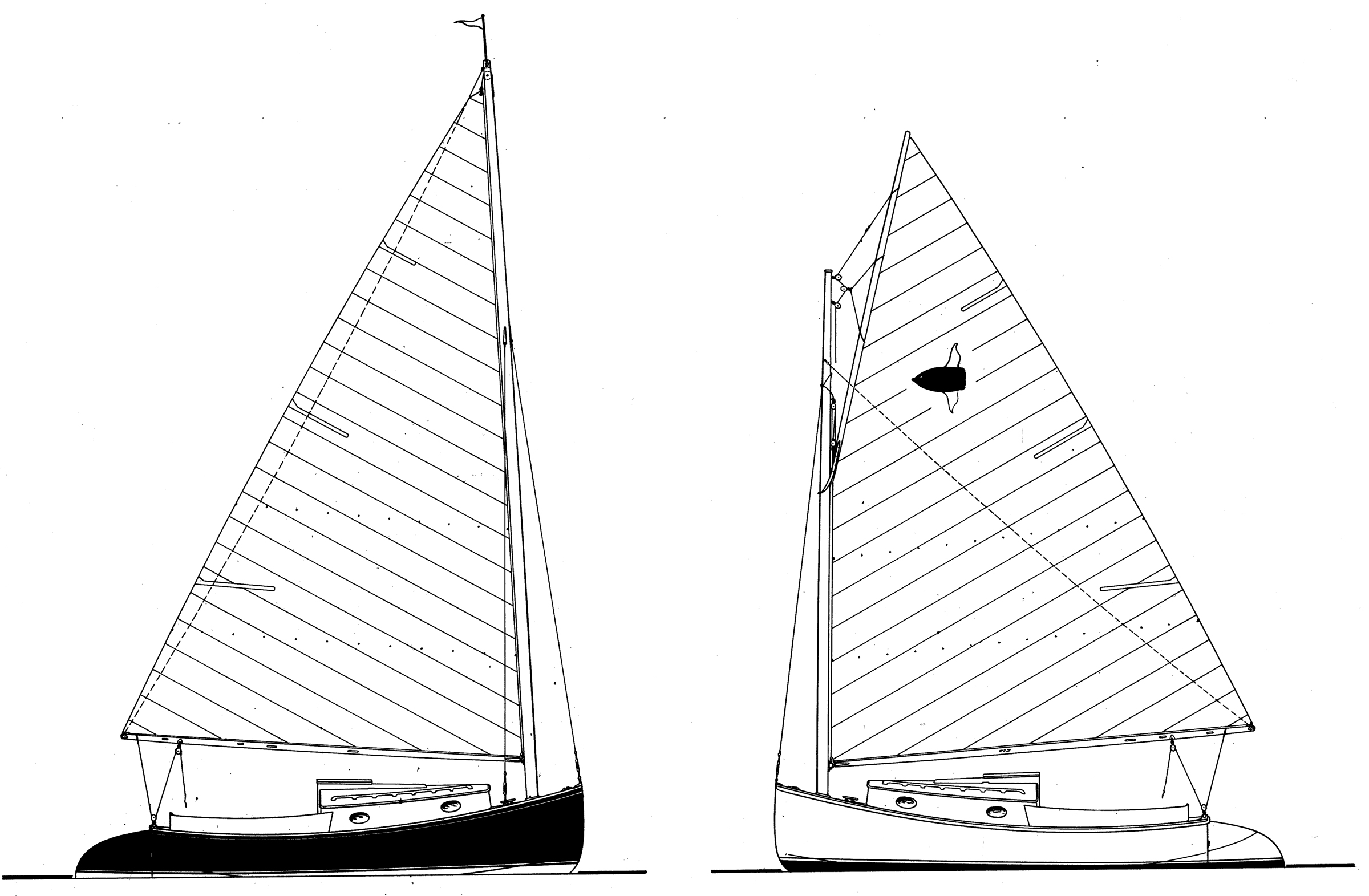

The plans for the 17′ 1″ plywood catboat include 11 sheets with good construction detail: materials, dimensions, fastening schedules, notes, and comments. Several alternatives are included: self-bailer instead of deep cockpit, lead-ballasted full keel instead of a centerboard, open cockpit instead of a cabin, gaff or marconi sailing rig, optional anchor-handling bowsprit, and an optional inboard engine. The plans date to the early 1960s, so some of the suppliers mentioned have long been out of business.

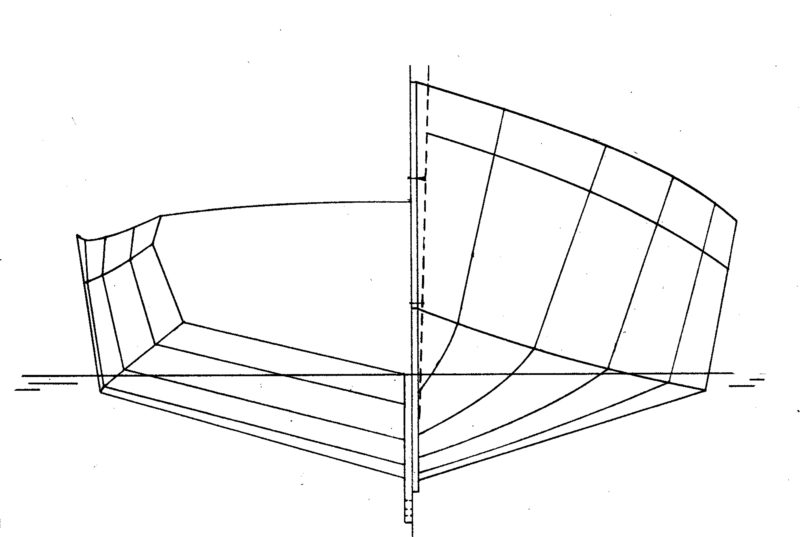

The Wittholz 17 requires lofting from the plan’s offsets. Drawing the body plan (the end-on view) requires a 6′ x 10′ drawing surface and is critical to loft accurately as it provides the full-sized patterns for the frames. The 6′ x 6′ side-view lofting of the stem provides patterns for the stem/forefoot assembly. The lofting for this catboat is not complicated; Greg Rössel’s book, Building Small Boats, covers lofting nicely.

Hull construction is straightforward: assemble the oak stem, the 1/2″ plywood transom, and the nine frames of mahogany or oak with 1/2″ plywood gussets. Set those elements on a level building jig, upside down, with the frames 22″ apart. Fit the mahogany or fir sheer stringers and chines, and the mahogany keelson to the frames.

The hull sides and bottom are 3/8″ plywood. The plans suggest a layer of fiberglass cloth on the ply for extra durability. I know from personal experience that if you get the catboat sideways to the wind and ram the dock, you can crack some plywood along the sides. The most vulnerable areas are between the frames forward of amidships, aft of the forward bulkhead. I suggest adding oak blocking between frames about 12″ above the waterline and heavy-duty fiberglass-epoxy on the inside of the plywood in these areas.

In my experience, fir and Aquatek plywoods check and crack if painted only, so they must be covered on both sides with fiberglass cloth set in epoxy. If you do cover plywood in fiberglass, do it after cutting pieces to shape, before installation, while they are still flat. This is so much easier than fiberglassing an assembled boat. High-quality okoume plywood is nice stuff: no voids, many plies. Okoume, when used for parts of the boat other than the hull, benefits from a barrier coat of unthickened epoxy on both sides, but it does not require fiberglass cloth.

This boat will always have a little water in the deepest part of the bilge. Seal this area with several coats of epoxy resin.

Get the sides from 5′ x 20′ panels (two sheets 5′ x 10′ scarfed). Attach the sides first. Get the bottoms from 4′ x 20′ panels (4′ x 8′ sheets scarfed). The bottom panels overlap the side panels most of the way then transition to a butt seam forward. Fit the keel to the keelson before turning the hull over.

The sail plans include both marconi and gaff rigs. The gaff-rig mast I built is solid spruce: 5-1/4″ in diameter, 25′ long. The gaffer requires a single forestay but no shrouds. The hardware called out in the plans is all from Merriman Yacht Specialties, a company no longer in business. Most parts have readily available equivalents, but if gooseneck hardware is hard to find, try wooden jaws. See William Garden’s article, “The Right Jaws for your Gaff and Boom,” in WoodenBoat No.59.

The gaff rig’s solid mast is too heavy and awkward to step handling it solely from the foredeck. Lacking a crane, it requires a person on a low bridge or atop a neighboring houseboat to steady the mast while a crew of two lifts/lowers on deck. Spare halyards from two neighboring sloops would also work to step this mast.

Those wanting a trailer-sailer will look to the marconi rig then make modifications for folding. The builder will have to design the modifications, because the plans say nothing about folding. The marconi mast is a 5-1/4″ x 4-1/4″ hollow rectangle, 32′ 3″ long. This mast requires a forestay and two shrouds that belay aft of the mast partner.

The gaff rig peaks up higher than is usual for a center of effort similar to the marconi. Build either sail with two sets of reefpoints as shown on the plans. The second reefpoint has a calming effect in 40-knot winds.

The optional bowsprit is not for a jib, as a jib of any kind would unbalance the boat. The bowsprit is for anchor handling, equipped with a chock to guide the chain and rode.

The Wittholz catboat has a centerboard, as catboats commonly do. Draft with centerboard up is 21″, down 4′ 3″. The centerboard case is 6′ long, most of it in the cabin, with 19″ extending aft into the cockpit. The centerboard itself is 3/8″ galvanized steel. There are 500 lbs of movable ballast in the form of lead pigs under the cabin and cockpit floorboards.

Monte Copeland

Monte Copeland The trailer for this keelboat version of the catboat is fitted with screw pads to steady the hull while the weight of the boat is supported beneath the keel. The centerboard version could slide onto a trailer equipped with bunks.

The plans include an option for a full ballast keel, as seen in the catboat pictured here. The draft of the full-keel version is 28″. The builder must make a mold to pour 600 lbs of lead shaped to fair with the deadwood in the keel. The mold requires lofting, too; refer to the Bud McIntosh book, How to Build a Wooden Boat, for a simple explanation.

Either model weighs about 2,200 lbs, including the ballast. The trailer for it could be a bunkboard arrangement, but a trailer with boat stands is better. When trailering, the boat must rest on its keel, not its garboards.

Monte Copeland

Monte Copeland With the tiller swung to port, there’s room for the stove when the cockpit is pressed into service as the galley. The plans call for an engine box, which would occupy the center of the cockpit. A transom-mounted outboard motor frees up that space for the crew.

The cockpit is seriously spacious. Sloop sailors often walk by and exclaim, “Look at all that room!” The cockpit can easily accommodate six people. The seats have a comfortable slope, and the coamings are tilted as backrests should be. The footwell is deep but not self-bailing. Water will sump to the deepest part of the bilge where a reliable pump awaits. For a self-bailing cockpit, see the plans; there is a sheet for that. The high sheer up forward keeps the cockpit dry in most conditions.

At anchor, it is a fine thing to hike up the sailing rig for standing headroom in the cockpit. On the gaffer, do this by furling the sail, lashing boom to gaff, and hauling on the peak halyard. For the marconi rig, modify the wire topping lift. Its upper end is fixed to the top of the mast, so modify the bottom end with 1/4″ rope, blocks, and a cleat on the boom to adjust it.

Monte Copeland

Monte CopelandThe plans for the cabin include two berths and cabinets aft of them, one equipped with a sink, the other a two-burner stove. The keelboat version, seen here, leaves the space between the berths unobstructed by a centerboard trunk.

In the cabin, there is sitting headroom on berths port and starboard. The two lockers amidships are sure to be customized by the builder. At anchor, a Coleman stove works well in the cockpit aft, so the two-burner alcohol stove in the cabin shown in the plans may not be required. The drawings show a head up forward, but it flushes straight into the sea. Better find a place for a porta-potty, either forward or perhaps amidships port or starboard. When it comes to building the cabin, How to Build a Wooden Boat is again a good companion to the plans.

The plans show where to fit a small inboard engine, but a 5-hp, four-stroke, long-shaft outboard motor serves well as an auxiliary. The plans also show an option for stowing an outboard under a hatch set in the cockpit floor. On smooth water, the outboard will push the boat at 6 knots. Mount the outboard to a bracket on the transom, but keep it clear of the big rudder. Add framing in the transom for attaching the bracket to the boat. The bracket should be adjustable up and down to keep the propeller in the right amount of water, no matter where the passengers are. Most 5-hp outboards come with a propeller suitable for light craft or inflatable dinghies. For a boat of this size and weight, select a propeller with less pitch so that engine rpms are high enough to avoid lugging the engine.

Sheila Harnett

Sheila HarnettThe 220-sq-ft sail here is held to the mast by hoops and lashed to the gaff and boom. The plans not using sail track along the boom.

In good conditions, expect this boat to sail to windward at 45 degrees off the wind. A sloop, with its two sails and narrower beam, might sail closer, but the catboat sailor specializes in his one mainsail and strives to get the most from it. The peak and throat halyards of the gaff rig provide control over sail shape. A three-part boom outhaul for either rig is useful to control the belly of the sail. The position of the crew greatly affects overall trim. Move crew aft or to windward to reduce weather helm, something catboats have in abundance. On this boat in particular, moving crew leeward can help push the hard chine underwater, so the side acts like a leeboard.

It is best not to oversheet a catboat. When hauled hard, the boom should be over the stern quarter of the boat. Hauled any harder, the boat slows down and crabs to leeward. Best to let out the sheet, find the wind, then adjust by looking for the sweet spot. On gusty days, do not cleat off the sheet; instead, wrap just enough turns around so it will slip when hit by a strong gust. On a reach, 15 knots of wind will move this boat at 6 knots. In stronger winds, reef the sail to match, preferably sooner than later.

At the helm, keep the tiller in one hand and the sheet in the other. One can sense immediately how the combination affects boat speed and trim.

This boat is built for comfort, not speed. What appeals most to me is how the Wittholz catboat provides so much space for its 17′ length. It’s a sailboat with berths for overnighting, and yet is buildable in a 20′-deep two-car garage. Over the years, I have come to appreciate its comfort, safety, good looks, and ease of sailing singlehanded. If I could add one thing to the plans? Fishing rod holders just aft of those stern cleats.![]()

Monte Copeland grew up in a lumberyard along the Ohio River, but never connected wood with water until after moving to Austin, Texas. Now retired from computer programming, Monte and his wife Sheila sail on Lake Travis. In his shop is an old Shellback dinghy getting ready for new paint.

Wittholz Catboat Particulars

Length/17′ 1″

Load waterline/16′ 6.6″

Beam/7′ 9.5″

Centerboarder draft, hull/21″

Centerboarder draft, board down/4′ 3″

Keelboat draft/28″

Displacement/3,080 lbs

Gaff sail area/220 sq ft

Plans for the Wittholz 17′ catboat are available in print and digital format from The WoodenBoat Store for $90.

Plans for the Wittholz 17′ catboat are available in print and digital format from The WoodenBoat Store for $90.

Thanks to reader Dick Lafferty for suggesting we review the Wittholz catboat—Ed.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Monte,

Thank you very much for this article. I’ve built 2 wooden boats so far, one clinker and one stitch-and -glue plywood. I’ve looked many times at the lines of the Wittholz 17 and admired her beauty. You’ve brought her to life for me and provided a lot of food for thought.

Cheers,

-Dick-

Mr Wittholz knew how to make a graceful boat! My first new boat, purchased in 1967, was a Chrysler Marine Lone Star 13. I had owned a $300 Philip Rhodes Penguin for just a month and sailed on White Rock Lake in Dallas. I quickly fell in love with the Lone Star 13s. What hooked me were two things: 1) their graceful, perfectly drawn sheer, and 2) the curling bow wave that the hollow in their forward section formed. I was sailing the Penguin one day when an LS13 came alongside and the skipper told me he had a customer who was looking for a Penguin and asked if I’d be interested in trading mine for an LS13. I (foolishly) assumed he meant a straight-up trade and gave him my phone number. He called that night and offered me $300 for the Penguin, but also offered to help me finance the LS for $30/month. I took him up on it and my only regret is that I didn’t keep that little Lone Star.

Great article. The Wittholz 17 has been on the top of my “someday” projects for a long time.

Re Fiberglassing flat plywood panels. Be aware that plywood with fiberglass is a lot stiffer than a bare piece of plywood. Some designs feature significant conical development and a fiberglassed panel will resist the conical bend. If you find yourself with this problem, the only solution is to remove the fiberglass with a heat gun, install the panel, and then fiberglass in place.

A lot of amateur boatbuilding is figuring out how to correct mistakes!

You raise a good point about flexibility of a fiberglassed panel. Other drawbacks to applying fiberglass to panels before use are that you miss the opportunity to span seams for reenforcement and cutting and planning the edges is hard on tools.

It’s with great interest that I read the article on the Charles Wittholz 17-1/2′ catboat. I own a fiberglass version of this boat, built in 1974 by Cape Cod Shipbuilding, in Wareham, Massachusetts, in 1974.

Sailing the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia is beautiful, but demanding territory for a small craft, but this design is totally up to the task! In the four years I’ve owned this boat, I’ve come to trust its ability to handle open water, and its ability to gunkhole in and around bays and islands, with its shoal draft, and retractable centerboard.

My boat has the original gaff-rigged mainsail, with two sets of reef points. I have rigged single-line reefing system, as I single hand the boat, and led the lines back to the cockpit. I have added a boom gallows in place of the removable boom crutch. This also allows for tackle to be rigged to help raise and lower the 6-hp four-stroke outboard on its folding bracket.

Other upgrades include cabin-top hatch for ventilation, bulkhead-mounted compass, and marine head. Planned future upgrades include installation of a tabernacle to enhance the trailer-ability of the boat. I would love to hear from readers with plans/photos of how to do this.

I would encourage your readers to consider this time-proven design, as a salty, capable, pocket cruiser that’s well worth the time and effort to build!

I also have a CCC 17’ Whittholz design, purchased in 1978 by my father. I went with him to Wareham, Massachusetts, to pick it up when I was 18. He sailed her mostly in Ohio and Florida. Fast forward 40 years, we moved him and the boat to Oregon in 2008 where he lived out his final years. We sail on a wonderful inland lake not far from home and enjoy sailing April through September. This boat has been my pride and joy and is always complimented when we sail by other boats.

I live in Portland Oregon, turned 80 in November and own a 17ft. Whitholz/Herman Cat. It needs some small attention anyone wanting to share information or look at my little project feel free to contact me*. Just read the article about Whitholz. I just saw the photo of Sandy Shaffer’s boat in your magazine and it would be nice to talk to her.

*Leave a comment here. We’ll forward it.

—Ed.

The article about the Wittholz 17′ Catboat naturally interested me. In my opinion, it is the best looking and most useful of any 17’ boat I have ever seen. It is just good to look at; Wittholz had the nautical eye. To achieve a good-looking boat in something so short and squatty is a miracle. It is the mark of a real artist. I think his little 17-footer answers all of the desiderata. And for me, it even satisfies my love of engines, in having an inboard diesel. But it is also my eye that is pleased. I love the perfection of his retroussé bow. It is just right.

I met Charles W. Wittholz. He was unpretentious, just a boat guy who had great talent. Conversation was easy with him. My buddy Tony used to have a catalog of his steel boat plans. Sadly, Tony threw that catalog away. I wish I had it. The catboat would not have been included in those plans. And because I had seen that catalog long before I had seen my own catboat and long before I met Wittholz, I associated him with steel yachts.

Tony loved his 42’ketch. He thought of building it or having it built by Dennis Schreiber. We were visiting Schreiber in St. Augustine at the time when Wittholz just happened to stop by to talk with Schreiber, who was building one of his steel boat designs at that time. Wittholz was a normal-sized man, wearing shorts and just a plain short sleeved shirt and looking like an everyday guy. He wore glasses. His hair was dirty blond. You could see how much he loved boats in every word he said. He quizzed Shreiber on whether his plans needed any reworking. He asked questions on some technical issues of construction. What was obvious is that Wittholz not only wanted his plans to produce a beautiful boat, he wanted the technicalities of construction to be good. Strength, convenience, maintainability, and practicality of construction, were all concerns of his. You could see he did not approach boat designing casually. The very construction of the boat was a matter of importance. I can’t remember for sure, but it is possible that Schreiber told him of some small little tricks he had come up with to deal with a special aspect of the construction.

Working with steel, of course, is a lot different than working with wood. And oddly, many of Wittholz’s designs could be built out of wood as well as steel. For example, my friend Tony has both the wood plans and the steel plans for Wittholz’s 42-footer Cutter/Ketch yacht. This babe is everything a man could want in a yacht. It was Wittholz’s answer to the SPRAY. Want to sail the Magellan Strait? It could do it.

Until meeting Wittholz, I had always imagined a naval architect as being a very formal man, on the order of Phillip Rhodes or Nat Herreshoff. But in Wittholz, I was seeing a man who could be out there in the boat yard painting his boat. But once he started to talk, you knew you were dealing with the real thing. Surely, he is among the truly talented boat designers. I do value it highly that I met Charles W. Wittholz.

Great advice about reefing. Sailing a Herreshoff America 18 in Florida’s intracoastal, I would take in one reef before leaving the somewhat sheltered dock and shake it out when I reached open water if the breeze was light. That was much easier, single handed, than the other way around.

A beautiful boat, a true pocket cruiser. Excellent write up. I, too, have pored over the plans for many an hour; now, if we did not already own two catboats….

I would offer this as a possible approach to hinging your mast: you may wish to read Dave McCulloch’s article in which he uses three 1/4” SS plates with bolts and pins on his 4” diameter Marsh Cat mast. He has a similar system on his Kingston Lobsterboat. See WoodenBoat #237 M/A 2014 page 38 “A Simple In-Mast Hinge.” Note that he added side stays. I have seen his installation; it is clean and neat. He brought the boat to a Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival to much acclaim. You may wish to check with David regarding plate size for taller masts. I have a set of plates all cut out but can’t bring myself to saw my mast in half.

Bill Rutherford

CACTUS WREN

Could Bill Rutherford put me on to Bill McCulloch? I am building a Marsh Cat and plan to use a tabernacle for the mast.

After much noodling, l’ve reinforced the deck from underneath using a piece of an old 4″D bird’s-mouth mast perched on the oak mast step and an oak deck pad. The tabernacle design is still in the works.

Cheers,

Robert Hale

PS: I cruised on a steel Wittholz Departure 35 from Guatemala to Gulfport, Miss. Good sea boat.

I recently got an early Ted Herman version of the Wittholz 17, with the Marconi rig.

I recently restored my ’71 Herman 17 with a Marconi rig. I’m concerned with the mast bend I get in the upper portion at the diamond shrouds when close hauled under full sail. Being a sloop sailer for years, I am not familiar with tuning this setup. Diamand shrouds are not adjustable but possibly have stretched?

I am in the process of buying a 1973 Wittholz/Cape Cod Shipbuilding Catboat, so Monte Copeland’s article is very valuable. As a fellow Austinite, I would love to meet or speak with him.

Chris, I always look forward to the 1st of each month and the new issue of Small Boats Magazine. The ARCHIVE feature is an incredible bonus, especially for those of us of a “certain age,” since we can read again those articles of a few years back that seem as new as the latest issue!

I’m looking to build the 14′ or 17′ Wittholz cat boat and wondering what would be involved in using cedar strip and instead of plywood to get the rounded lines?

I built a Wittholz 17′ cat at around the same time as Monte Copeland and have been sailing it in Belfast Lough (the original one in Northern Ireland) for some 14 years now. I was able to exchange a few emails with Monte at the time we were building, which helped a lot to encourage me to keep going! I also had great advice from Dan Whiteneck who was building one near Boston, but I have unfortunately lost touch with him.

The boat attracts admiring looks and compliments from all who see her and has become part of my life. Looking forward now to the summer for leisurely and surprisingly quick sailing in my unique Wittholz cat.