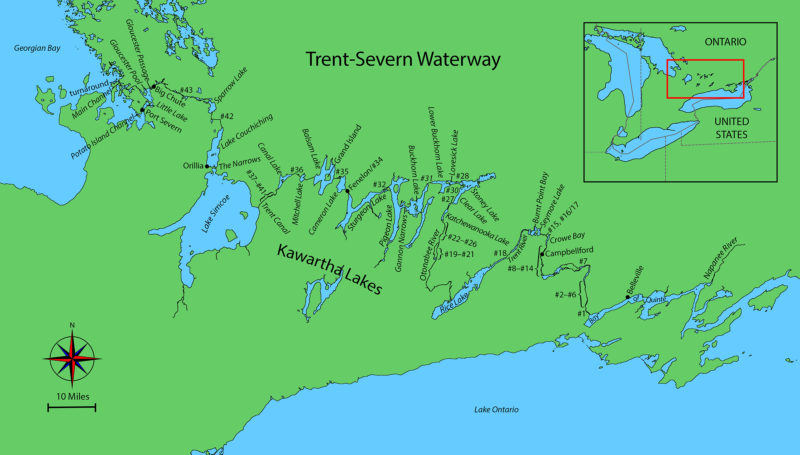

As the wakes of passing powerboats slapped SOUL CAT’s port side, she rocked gently. I was in a secluded part of Georgian Bay; the nearby island’s black and red granite outcrops had been smoothed and rounded by ice-age polishing. White pines and brush partially concealed a pair of plain, two-story cottages. These were new to me, but otherwise the low 1⁄5-mile-long island, unnamed on the charts, was much as I remembered from a 1960 camping trip with my dad, brother, and cousin. On this day, August 13, 2022, I had reached the turnaround point in a voyage from my home in Napanee, Ontario, up the Trent-Severn Waterway—a 240-mile chain of rivers, lakes, locks, and canals from Lake Ontario to Lake Huron— and back again. I was 290 miles and 11-1⁄2 days from home.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThis island at the entrance to the Main Channel from Georgian Bay marked the beginning of SOUL CAT’s homeward-bound journey.

Four solely solar-powered electric boats had previously made the east-to-west journey along the Trent-Severn: in 2017 the American boat, RA, was the first, coming this way during its Great Loop adventure; in 2018 I followed in SOL CANADA; in 2021 a catamaran yacht named THE HARVEST followed the waterway from Trenton, Ontario, to Georgian Bay but then looped back to Lake Ontario via Lake Huron and Lake Erie. Now, in SOUL CAT, I had become the fourth to make the trip and I hoped to become the first to make the 580-mile round trip on the Trent-Severn under solar power.

Inspired by a Small Boats review of Bernd Kohler’s gas-outboard-powered Eco Cat, I built SOUL CAT, a modified version of Kohler’s 18′ x 8′ plywood-on-frame catamaran. I had been using her for a year and thus far she had met my expectations. I had a Torqeedo electric motor, the equivalent of a 5-hp gas-fueled outboard, that pushed the boat up to a top speed of 6 knots.

SOUL CAT is propelled by a Torqeedo Cruise 2.0 electric outboard set in a well and powered by a bank of batteries housed beneath the forward bench. The sixteen 3.5-volt lithium-ion phosphate batteries are configured to provide 24 volts with a capacity of 10kW. The boat is capable of a top speed of 11 mph but cruises at an average speed of 5.3 mph. The batteries are charged by eight flexible solar panels in two arrays on the canopy. They have a rated output of 660 watts for the first string of three and 900 watts for the second string of five, giving a total theoretical capacity of 1,560 watts, which is rarely, if ever, achieved because of adverse conditions: the angle of the sun, the hour of the day, cloud cover, etc. The canopy is supported by four motorized struts that can lower the canopy 30″ to rest on the bulwarks for trailering and control the port-to-starboard tilt of the canopy to maximize solar performance.

I turned SOUL CAT from the unnamed island and retraced my route along the crooked 4 miles of the Main Channel toward my overnight destination, Port Severn, 15 miles to the southeast and the site of Lock 45, the most north-westerly lock of the Trent-Severn Waterway’s 45 locks. I cruised in the shadow of high pine-topped granite cliffs along a channel well-marked with buoys as well as day markers on posts and low rock prominences. This midsummer Saturday, boats were flying back and forth, heedless of the speed limit and oblivious to the cresting wakes they dragged behind them. As slow and as light as SOUL CAT was, I felt like I was riding a scooter on the freeway and motored cautiously through the the chaotic intersecting wakes. After a few hours I reached Port Severn and settled in for the evening at the public dock just around the corner of the upstream end of the lock.

SOUL CAT settled in for the night with the side tarps rolled down for shelter and privacy. The cockpit has an aft bench seat and two forward bench seats that fold down for sleeping. A small sink, countertop with hinged table leaf, and a double-burner propane stove serve as the galley. There are two coolers, one for refrigerated food and one for fresh produce. Up forward beneath the ’midship benches, there is plenty of storage space for clothes and tools. The canopy is canvas over an aluminum frame, while the roll-down sides are made from an inexpensive tarp attached, fore and aft, to large bug screens.

The next day dawned shrouded in cool mist so thick that I could not see across the harbor. I took my time over a cup of coffee and tidied the boat while the sun slowly burned off the mist until there were only smoke-like wisps above the barely rippled water. I cast off and ventured into Little Lake with its dark clear water and banks of granite, peppered with maple, birch, and pine that veiled the dozens of cottages crowded along its shore.

Most of the lakes along the waterway are natural, although a few were created as the canal was built and surrounding land was flooded. Construction of the Trent-Severn began in 1833. Linking natural lakes, rivers, and streams across 240 miles, it was hoped that the waterway would open Ontario’s interior and promote agriculture, the lumber industry, and general commerce. It was almost 100 years in the making, and by the time the waterway was completed it was no longer viable—cargo ships on the Great Lakes had grown too large for the canal, and the railways had expanded and were now taking freight overland. From the day the waterway was opened it became a route for pleasure craft, now operated by Parks Canada and open to navigation from May to October.

At the far end of Little Lake, the channel wove through a maze of tree-crowned islands. The channel markers guided me around a northward bend to Gloucester Pool, a 3-1⁄2-mile-long lake where cottages perched on the steep sides of the lakeshore and on the offshore islands were often obscured from view by the trees; long docks extended from the wooded slopes out into the lake.

At the eastern end of the lake is Gloucester Passage, a zigzagging channel that narrows to 25 yards where the swirling Severn River current flowed so fast that I worried my motor, capable of only 6 mph on still water, wouldn’t have enough power to maintain steerage. I made it through, slowly, and without having to contend with any fast-moving boats squeezing through the narrows. Less than a mile farther upstream I reached the Big Chute Marine Railway.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

As early as 1914 there were plans to build a lock to bypass the Big Chute rapids, but construction was interrupted by the World War. The first railway, intended as temporary, was built in 1917 and has been replaced twice. Today, there is a flat-bed carriage 100′ long and 24′ wide. It is the only railway of its type still in regular use in North America. The carriage descends into the water so that a boat can be driven on over its submerged platform. Once the boats are secured, cables pull the carriage up the 60′-high granite slope and down the other side back into the water. The front and rear wheels of the car ride on separate tracks set at different levels so the carriage stays level as it traverses the hill.

As I approached the railway, a single boat was departing, and I motored straight on and had the carriage to myself. In barely 10 minutes SOUL CAT was floating off and I head for Swift Rapids, Lock 43, just 8 miles upstream.

There was a light headwind and the sun shone down from a clear sky, ideal for solar-powered travel the panels generated almost as much energy as the motor was drawing. I arrived at the Swift Rapids Lock along with about a dozen boats ranging from cutters to personal watercraft and we all crowded into the 120′-long lock. There once was a marine railway like the one at Big Chute, but it was replaced in 1964 by what became known as the Giant Lock, the deepest single-chamber lock on the Trent-Severn, which carries boats through an average lift of 47′. When the lock gates opened at the top of the ascent, the other boats all took off and I was soon left behind, once more in peace and quiet.

On SOUL CAT’s port side, is the pop-up cabinet that encloses the head. When the head is in use the upper section of the cabinet is raised; at all other times it is lowered to this height and provides a useful work surface.

The landscape was now flatter, and the channel wound maze-like through inlets and outcroppings. For the first 1-1⁄2 miles there was only a single cottage, snug on an island scarcely larger than it was. Traveling upstream into a headwind and plowing through mats of weeds made for slow going. After a 2-mile crossing of Sparrow Lake, I entered a narrow stretch of river where the flat banks on either side were again crowded with cottages. The powerboats here traveled slowly, providing welcome relief from their wakes. At points along this 4-mile run, the river was so narrow, and the buildings so tightly spaced that neighbors on either side of the waterway could converse with one another while standing on their docks.

I arrived at Couchiching, Lock 42, made the 20′ lift, and moored for the night on the upstream side at the last vacant spot on the low wooden dock. The tall pines on the high banks blocked any wind there might have been. Next to the ash-gray cement wall, a faded-green picket fence lined the gravel trail that led into the woods.

I was awake and up by 6:15 the next morning and rolled up the side tarps. The morning mist was thick and hung over mirror-still water that reflected the surrounding pine, balsam, blue-beech, and maple trees. There was not a whisper of sound.

An hour later, I headed upstream on what seemed to be the river’s natural course with both sides thick in forest right to the edge of the low-lying shore but was a 1.6-mile-long canal that had been cut by hand a century ago to bypass the last stretch of the Severn River en route to Lake Couchiching. The lake is 10 miles long and up to 3 miles wide with a well-marked channel to keep clear of its shoals. I was pleased with the gentle following breeze and the bright sunlight shining on the solar panels. When I first attempted this round trip four years ago, the end of sunny weather had forced me to stop at Lake Couchiching after 377 miles in 16 days. Now, four years later, I was breaking my distance record and was two days ahead of the 2018 schedule.

There is typically little solar benefit to be gained when cruising in the early morning and at 8:15 a.m. the panel was producing only 250 watts while the motor was drawing 800 watts to maintain 5 mph. My battery budget was to draw no more than 600 watt hours from the 10-kilowatt battery bank so I could travel all day and finish the day on a full charge. As the day lengthened, the solar energy increased and the panels produced more and more so that, at times, I could be traveling at 5 mph and yet have a trickle charge into the battery. The power management game was to balance speed and draw—on an overcast day, I would drop the speed and exponentially drop the draw.

At its southern end, Lake Couchiching leads to the city of Orillia and Atherley Narrows, a 50-yard-wide marina-flanked passage that flows beneath a busy highway bridge and on to Lake Simcoe. At 15 miles wide and about 22 miles long, it’s largest lake on the Trent-Severn Waterway. Like Lake Couchiching, its waters are shallow, and a strong wind can swiftly build rollers into large breakingwaves . During the crossing from the east side of the lake in 2018, I had had to slow to 3-3⁄4 mph to keep whitecaps from washing over the bow of SOL CANADA. This time I was in luck, the day was calm and sunny and as I crossed the northeast section of the lake from Orillia to the canal, I was struck by the vast expanse of the blue-green water. I could see no land on the horizon, and seagulls and cormorants flying over were the only signs of life. The marked channel never more than 3 miles from shore, the wind remained light and at my back, and I made good progress.

At the top of Couchiching, Lock 42, SOUL CAT is nestled between two yachts. In the center of the cabin space, the portable toilet enclosure is in its raised position, which provides plenty of seated headroom.

Exactly 5-1⁄4 hours after leaving the dock at Lock 42, I rounded Mara Point, a blunt headland on the eastern shore, and approached the two limestone-rock breakwaters that jutted 250 yards into the lake to protect the canal’s 45′-wide entrance. I looped SOUL CAT around to steer north into the entrance then northeast along the still waters flanked by 6′-high concrete walls that were equipped with mooring bits and iron ladders. On the landward end of the breakwaters, I passed through a blue-painted steel swing bridge and waved at the lone Parks Canada operator. Steering clear of the weeds in the shallows close to the banks, I headed northeast along a narrow 1-1/8-mile straight stretch of canal up to Gamebridge, Lock 41. Instead of the granite rock formations and tall pines of the Severn River and its lakes, layers of limestone, overgrown with scrub brush, cedar, and small white pines, lined the banks, making it impossible to pull into shore. The weeds were thick, and the propeller snagged some that grew from the canal bottom as well as those ripped up by passing boats that gathered into floating islands.

When storms kick up swells on Lake Simcoe, the breakwaters at the narrow dogleg entrance to the Trent Canal give shelter to boats waiting to head out.

On both sides of Gamebridge Lock the walls were painted with a blue stripe, which is standard for all manned locks on the waterway: a boat moored in the blue area waits to pass through. A boat in an area not painted blue is there for a short stop or overnight. The walls leading to and from the lock were again 6′ high— a protective measure in case of a storm surge from Lake Simcoe—so I had to climb a ladder to reach the bollard at the top. I was alone passing through the lock and glad I chose to travel in late August when there is a lot less boat traffic than in July.

Beyond Gamebridge, a series of four locks is separated by as little as 1⁄2- to 1-1⁄2 miles. The shortest stretch, 2⁄3 mile, from Gamebridge to Thorah, Lock 40, was little more than a straight ditch, bordered by flat fields and banks devoid of vegetation, shored up by large limestone rocks. The canal was almost choked by weeds in some sections, and I was forced to stop and clear them from the motor’s shaft. As I got underway again, I saw two cabin cruisers waiting to enter Lock 39 and hurried to catch up to them. The lock tenders contact one another about how many boats are coming their way so that they can lock a group of boats through together. I didn’t want to be the slow poke holding all the others up, so I throttled SOUL CAT up to a blazing 6 mph. SOUL CAT and the other two boats passed together through Locks 39, 38, and 37—Portage, Talbot, and Bolsover.

Leaving Bolsover, I let the cabin cruisers pull ahead of SOUL CAT—Lock 36 was 7-1/2 miles away and she wouldn’t be able to keep up. The canal widened, and the shoreline became a series of small irregular inlets and bends crowded with cottages. I had to wait only a minute for a swing bridge to open before entering the 5-mile-long Canal Lake. I was pleased to have come this far, but the weather was no longer in my favor: a 4-mph headwind was slowing me down and the sky had become overcast, making it difficult to get a good charge.

Canal Lake was manmade after the canal was built and the area flooded. A wide, grassy body of water, the lake is at the western end of the Kawartha Lakes, chain that forms the upper watershed of the Trent River. The channel was well-marked but narrow between shoals and areas of dense weed. I worked my way along the well-marked channel between shoals and areas of dense weed, into the building headwind. The lake was divided by three islands connected to one another and to the lake shores by highway bridges. The channel took me to the concrete arch bridge on the south side of the lake: its 60′-wide semicircular arch, mirrored in the breeze-rippled water, looked like a hole in the wall leading to the second half of the lake. I passed through with fanciful expectations, but it was more of the same: a 3⁄4-mile-wide, grassy lake with weeds that stopped me several times to clear the motor.

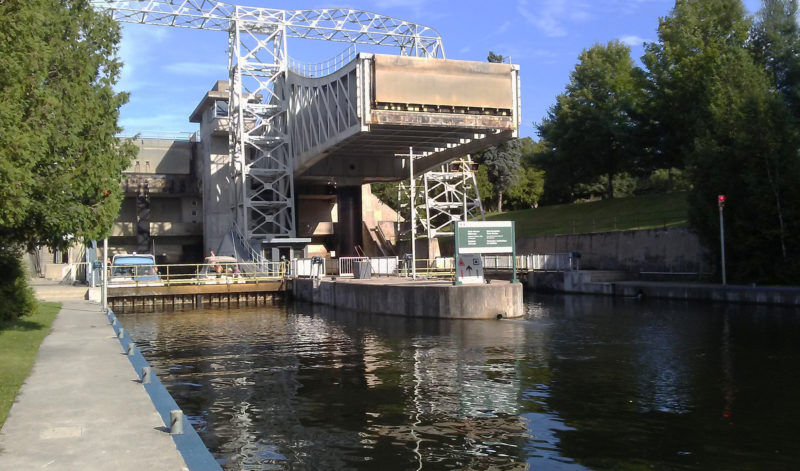

At the northeast end of the lake, I entered a narrow channel that led to Kirkfield, Lock 36, one of two hydraulic-ram lift locks on the Trent-Severn Waterway. It raises eastbound boats 49’ to the highest point on the waterway—840′ above sea level. I motored into what looked like a big bathtub, the sides and overhead a web of white-painted steel. The gate closed behind me, and up SOUL CAT and I went. The counter-balancing tub to my right was descending without carrying any boats, but the weight of the water in it was creating the hydraulic pressure that was raising me. Since there was no water flowing in or out of either tub as in a lock chamber, there was no turbulence. It was just a quick elevator ride up. At the top, I left the lift and decided to call it a day. It was 5:30, the lock was closed for the day, I had traveled more than 40 miles in just under 10 hours since leaving Couchiching, and I had the entire upstream half of the lock site to myself. The mooring wall extended along the channel for 1,200 feet on both sides and I stopped about a third of the way along—if anyone else showed up they would have plenty of room to tie up in seclusion. The only downside to my chosen spot was the long walk back to the lift lock, down the multiple flights of stairs and across the road to get to the washroom. Even so, I was content and after some supper and a quick swim in the cool water, I rolled the tarps down for the night.

Kirkfield, Lock 36, is the larger of the two counterbalanced hydraulic lift locks on the Trent-Severn Waterway. Its caissons are each 140′ long and 33′ wide. The rising caisson stops when its water level is about 1’ below that of the canal on the upstream side of the lock. When the lock gate opens, water flows into the caisson, increasing its weight by many tons. Simultaneously, the lower caisson stops when its water level is about 1′ above that of the canal on the downstream side. When its gate is opened, water flows out of the caisson, reducing its weight by several tons. Finally, when the valve between the cylinders of the pistons that support the locks is opened, the heavier upper caisson descends, forcing the lighter one to rise. Just 18 days after SOUL CAT passed through the lock on the homeward-bound leg, one of the gates at the top of the lock failed and the lock was closed. Kirkfield is expected to reopen in time for the 2023 boating season.

It was 7:20 a.m. when I left Kirkfield and puttered up the straight canal between the cement walls and walkway. About 1⁄4 mile from the lock I entered an equally narrow canal that took a sharp curve to the southeast for an arrow-straight 2 miles. Walls of intertwined cedars leaned out from both banks, their lowest boughs just inches above the water. In places, loose layers of limestone rose 10′ to 15′ above me and shrubs had grown in the fissured banks. Glass-smooth water reflected the trees and limestone making the canal appear even narrower and SOUL CAT seemed to be floating on a pathway of sky and clouds. It was a stark contrast to the granite landscape from just the day before.

I motored the canal slowly. The battery bank was still low and overcast skies and thunderstorms were forecast for the afternoon. The only sound was the gentle turbulence trailing each hull. The canal led into manmade Mitchell Lake. On one shore I could see wetlands with green weed beds and cattails. It was still early morning and there was not a soul to be seen except a leggy great blue heron perched motionless on a “No Wake” sign. Another straight and narrow 2-1/4-mile-long canal led to the 19 square miles of Balsam Lake, the top of the watershed. From here on I would be traveling downstream, the channel buoys switched from reds to my left to reds to my right, and all the locks—draining instead of filling—would be less turbulent.

The northeast breeze in the late morning was still light as I headed due east and then dipped south to round Grand Island’s rocky shores and sand beaches surrounded by yet more weed beds. It was a 5-mile crossing to the inlet at Rosedale that would lead to Lock 35. From the lock I continued through a marshy channel into and across Cameron Lake, and within less than 3 miles reached the village of Fenelon Falls at the mouth of the Fenelon River. There is wall space for mooring above Lock 34 and when I arrived, the upper mooring area was taken up by motoryachts, so I locked through and tied up at the concrete downstream wharf.

It was only 11:30 in the morning but since sun was scarce and storms were forecast, I decided to stop here for a rest day to allow the batteries to charge. From my tie-up I could see the long spillway where the river tumbled in an endless rumble of falling water which I hoped would lull me to sleep when I turned in. Downstream, the low concrete canal sides gave way to higher rocky banks of sediment limestone topped by pine, fir, cherry, and maple trees obscuring the view of simple cottages and two-story condos.

I wandered past the yachts, stopped to chat with one or two boaters, and strolled into town where the streets of Fenelon were bustling with traffic and shoppers. The sky soon turned dark, so I circled back to the boat and as I rolled down SOUL CAT’s nighttime tarps the skies opened and a torrent of rain came pouring down. I had made the right decision to stay in Fenelon. Within an hour, the rain stopped and my boat, once all alone in a quiet spot on the pier, had been joined by several other craft; the noise of the rain was replaced by the sounds of chattering neighbors.

Evening came and I went ashore for dinner at an eatery just a block away. Returning to the boat, the roar of the falls was drowned out by the sound of portable gas-powered generators as the yachts charged up their battery banks. The light breeze blew the exhaust fumes from one generator about 10′ away, straight at me and, rather than sit and choke on the fumes, I left to spend the evening at a pub. When I returned, as I had hoped, all was quiet.

I was up and gone before 7:30. The sky was overcast but there was no wind as I journeyed down the Fenelon River, which ranged in width but was generally about 150′ wide with high banks of many-layered limestone. After just 1 mile, the river opened into Sturgeon Lake and I headed south down the western arm of the Y-shaped lake with a light breeze behind me. It was a quiet morning, and I had the lake to myself. After 4 gentle miles, I took a sharp turn around the bottom of Sturgeon Point and headed northeast into the light wind that had previously been in my favor. Ten miles later I was at Lock 32 and the small town of Bobcaygeon that nestles between the north ends of Sturgeon and Pigeon lakes. Even this late in the season, the lock walls were lined with boats.

My route took me south through Pigeon Lake before winding east along Gannon Narrows into Buckhorn Lake. SOUL CAT had covered 30 miles upon arrival at Lock 31 at the lake’s north end. Boats staying the night filled the walls on both sides of the lock, but I managed to squeeze in before walking to the nearby grocery store to restock. I settled in early and after a peaceful night got off to a lazy start as I had to wait until 9 a.m. for the first lock-through of the day. By 9:15 SOUL CAT and I were through and cruising east under a hazy sky with a light following breeze. I had gone through the lock in a swarm of boats, but they were now spread out along Lower Buckhorn Lake well out in front heading to Lock 30, a 3⁄4-mile passage. I followed them through from Lower Buckhorn into Lovesick Lake. My route passed between rocky granite islands with jagged inlets and mature-growth trees hiding concealing small cottages and the mainland shore, where large summer homes stood before a backdrop of high rocky hills covered in maples, oaks, and balsam firs.

I left Lovesick Lake at Burleigh Falls, Lock 28. The channel downstream from the lock opened to an arm of Stoney Lake and 1⁄3 mile to the southeast along the shore the rushing water and spray of Burleigh Falls divided around a small island topped with a thicket of pines.

Beyond the falls was a cluster of islands that required close attention to avoid boulders, shallows, and other hazards. Stoney Lake has its name for good reason. I arrived in Clear Lake, a 4-mile-long body of water that stretches from northeast to southwest uninterrupted by a single island. Clear Lake also appears to have earned its name. Now I could head south in a straight shot to Youngs Point, Lock 27, at the head of the Otonabee River, which meanders southwest to Rice Lake some 33 miles away.

Otonabee, Lock 23, is one of 11 locks closely grouped together over a distance of 26 miles. The long cement walls are typical of all the lock stations on the waterway.

I still had many miles and several days ahead of me, but it was beginning to feel like the homestretch, and I was determined to push on as far as I could. My goal for the day, if all went well, was to make it through another eight locks to end just below Ashburnham, Lock 20, in the heart of Peterborough, 15 miles away. On the downstream side of Youngs Point the Otonabee began as the 5-mile long, 1⁄2-mile wide Katchewanooka Lake and its waters reflected the overcast sky and surrounding evergreens. The rocky shores were giving way to flatter, lower-lying land with the occasional wetland. At the south end of the lake, in the town of Lakefield, I passed through the first of five locks, 26 through 22—Lakefield, Sawer Creek, Douro, Otanabee, and Nassau Mills—all with little to distinguish them, and all within about a mile of one another. A drizzle of rain started and stopped and started again. Moments after I left Nassau Mills, a peal of thunder rattled overhead. If it continued or lightning appeared, the locks would close. It was getting late in the day and I had 4 miles to go to reach the next lock so I poured on the power—1,400 watts—and sped along at 6.4 mph. At 5:15, just 15 minutes before closing, I arrived at Peterborough Lift, Lock 21. The second of the waterway’s two lift locks, Peterborough differs from the Kirkfield Lock only in its greater drop—66′ instead of 49′. SOUL CAT was gently lowered in a matter of minutes. I had planned to spend the night upstream of Ashburnham, Lock 20, but boats aren’t allowed to spend the night between Locks 21 and 20, so I made the ¼-mile sprint to Ashburnham, locked through and was done for the day. I was pleased with the day—eight locks and 31 miles despite the clouds and rain.

While SOUL CAT waited for Lock 19 to open at Scotts Mills on a sunny Saturday, her canopy is tilted 5 degrees, which doubles the solar performance in the early-morning light.

Saturday morning dawned bright and sunny, not a cloud in sight and not a whisper of wind. I was up early and had to time to bide until the 9 a.m. opening of Scotts Mills, Lock 19, just 3⁄4 mile down the Otonabee. In the Ojibwe language, the river is called Odoonabii-ziibi, while the word Otonabee comes from the Ojibwe ode, meaning “heart” and odemgat, meaning “boiling water.” In essence the name translates to “the river that beats like a heart and passes through the boiling water of the rapids.”

At 12 percent, my batteries were dangerously low, but I could get a trickle charge going by motoring slowly and taking advantage of the almost-2 mph downstream current. I arrived with an hour to spare. Scotts Mills was bathed in sunlight but there was a constant clatter echoing in the still morning air from the construction work on the dam. I tied up and tilted the canopy to a 5-degree angle to make the most of the sunlight. I was surprised to see the power production surge from 200 watts to 435 watts even at 8 a.m. and decided to lock the canopy in this position for the upcoming run south. When the lock crew came on duty and opened the gates I silently slipped into the lock as the sole occupant and within a few minutes SOUL CAT was heading downstream at 4 mph drawing 480 watts but generating 550 watts—very good for 9:20 in the morning with the sun low in the sky—leaving 70 watts to trickle charge the battery bank. Later in the morning that rose to 150 watts.

The 18-mile stretch of river wove its way through lowlands with marshy pockets, and between banks crowded with overhanging trees or whose bottom branches skimmed the water’s surface. There were only three bridges, a few cottages, and clearings around beaches. As the morning advanced and the charge going into the batteries rose, I upped the speed to 4.5 mph and was still generating a charge of 200 watts.

The river at last opened into a shallow delta and flowed into Rice Lake, a 20-mile-long, 2-mile-wide, northeast-southwest, shallow lake. It can be rough on windy days, but this day it was calm and I headed northeast toward Hastings with a gentle wind pushing SOUL CAT from astern. As I neared the top end of the lake quickly moving black clouds were coming at me and there my luck ran out: the rain came in a downpour and the wind whipped the canopy so hard it snapped like a flag. I worried that the solar panels might fly off completely. The wind spun SOUL CAT around and I fought to get her back on course. Then, the squall moved on just as suddenly as it had arrived. I was soaked, the boat was soaked, but we were in one piece. I pulled into the Trent River and on to Hastings, Lock 18.

The drizzle thinned, and as I arrived at the lock’s cement wall, the sun was peeking out. Despite the quick summer storm, it had been a good day’s travel—39 miles. I moored just upstream of the lock in the very heart of Hastings, a small Ontario town with a year-round population of about 1,300, and popular with summer tourists. I was moored next to a quiet park land with picnic tables, and just a short stroll from a few restaurants, a grocery store, and an ice-cream shop—Hastings had everything I needed.

A sunny day had been forecast for the following day but at 8 a.m. there was a thick fog. My plan was to start slow, as I had done the day before, with the hope of trickle charging the battery bank and to get as far as I could while the weather held—the forecast for the next few days called for rain. At 9 a.m. the lock opened. The fog had all but burned off and I entered with one other boat to lock through.

Crowe Bay, Lock 14, seen here as water was being released from the chamber, was where Phil installed a spare propeller to replace the motor’s original prop after it struck a submerged rock shortly after leaving the lock.

The banks of the Trent River were thick with cottages and homes on one side and low, grassy wetlands on the other, while between them the river itself was translucent blue. It was 50 miles to the Bay of Quinte on Lake Ontario, but there were 17 locks to go through. I made my way through flat countryside as the river opened into Burnt Point Bay and the adjoining Seymour Lake before narrowing down again. There was little traffic, and I was alone in the three locks—17, 16, and 15—that parallel the last mile of the Trent River before it empties into Crowe Bay, the reservoir created by the dam at Lock 14. To the west of the lock, long gentle falls and small rapids flowed from the dam spillway over 150-yard-wide ledges before slipping back into the channel, which was rocky and, in places, shallow.

Perhaps I was tired, perhaps I didn’t see that the marker buoy had moved out of its location, but the prop hit a rock. The impact jarred the boat, and I knew that all was not well. One of the propeller’s three blades had broken off, but I had enough propulsion to hobble back to the lock entry wall at Crowe Bay. Fortunately, I had brought two older props as spares. The water was too deep to stand in to change the prop, so I tilted the motor up as high as I could, tied a rope around my waist, and, with socket wrench carefully in hand, leaned far out from the wall to get over the motor. I managed to remove the prop nut, replace the propeller, thread the nut back on and tighten it up without dropping anything. Everything worked as it should and I was once more on my way, but I hadn’t gone far when someone at the end of a dock was waving frantically at me. It was my buddy Phil from Belleville, who had been following my voyage with a tracking app. We talked briefly and agreed to meet up after the Ranney Falls locks, just beyond the town of Campbellford.

After an uneventful downriver through Lock 13 and past Campbellford, I arrived at the entrance to the flight of Ranney Falls, Locks 12 and 11, and set up for the night. Phil paid a visit for a couple of hours and after he departed, I hunkered down for the night only to be woken in the early morning by the pounding of a heavy rain. By 9:30 a.m. it had eased to a light drizzle, so I packed up, headed into the back-to-back locks, and then went on my way, once more the only boat heading downstream.

The day was warm, the rain had stopped, there were breaks of blue in the overcast sky, and no wind to speak of. The river passed through a protected wetland area, the acres stretching away through maple, oak and cedar, mixed in with areas of grass, shrubs, cattails, and weeds. The water was now a murky green, a far cry from the clear blue upstream.

By the time I had navigated 5 miles and descended Locks 10 and 9, the rain had started again. It seemed that this would be the theme of the day and I decided to make Glenn Ross, Lock 7, about 12 miles ahead, my destination for the day. The river was narrow, and the low land continued along both sides, but the water was obstructed by a weed growth that looked like floating palm trees. It was a species I had never seen before and later learned that it is an invasive called water soldier. Before it was prohibited, it was sold as an ornamental plant for water gardens. It escaped into a few areas of Southern Ontario and efforts are underway to contain it before it crowds out native species and clogs the waterways. I dodged my way through the spiky leaves, passed through Percy Reach, Lock 8, and made the final 11 miles to Glen Ross, where I pulled in at the top of the lock for the night. An isolated spot, it had just one variety store where I picked up a jar of coffee and later went back for a dish of ice cream.

In this early-evening view looking downstream from the top of the lock at Glen Ross, the section of blue-painted wall is reserved for those boats waiting to lock through. Boats tying up and not wishing to lock through must avoid this area.

The next day was again overcast but I motored the last 14 miles and through six locks to arrive, at last, downstream from Lock 1 and just a mile from the Bay of Quinte. I moored up to the lower wall of the lock, and spent a restless night disturbed by trains crossing the nearby bridge and the rain hammering on SOUL CAT’s canopy.

In the morning I tilted the canopy all the way to port to clear the pool of water that had accumulated in the canvas awning beneath the solar panels. The final stretch of canal was contained between cement walls for 1⁄4 mile. To starboard, the land rose in a 20′ barrier mound topped by a scattered border of sumac trees and separating the canal from the streets of Trenton. To port, beyond the cement, were low scrub trees and brush on a strip of land that separated the canal from the fast-flowing, unnavigable Trent River.

I motored the final 2-mile stretch of canal and beneath the last bridge before turning to look back at the “Gateway to the Trent Severn Waterway” sign that spanned the bridge. I had become the first person to have completed the Trent-Severn Waterway in both directions, solo, using only 100 percent solar electric power.

Making my way east on the Bay of Quinte, a 30-mile-long east-west inland bay that runs parallel to Lake Ontario, my destination for the day was the city of Belleville where I would meet with friends at a small restaurant tucked away near the harbor. I was not to be given an easy ride, however. A head wind and cloudy sky made for slow going and it would be a few hours before I arrived. Then, just as the downtown restaurant came into view, the sky opened and pelted me with rain. It was an unpleasant arrival, but I tied up, mopped up, and joined friends Dave and Phil for lunch. As I sat there, my granddaughter, Taylor, sneaked up behind me bearing a large sign saying, “Congratulations Papa!”

While I had done what I had set out to do, I was not home yet and still had to figure out the next 24 hours. Dave made a quick call and said I could use the mooring space of some friends at the local yacht club for the night and so off I went just as another downpour started. After I’d moored for the night, I had visits from several friends—Belleville is where I worked for 37 years before my retirement.

The morning of August 24 broke to sunshine and a light westerly breeze. I set off on the final leg of my journey to my home dock on the Napanee River about five hours away. The Bay of Quinte was quiet, and as I turned into the Napanee River it felt good to be back in my home waters. I was welcomed at the dock by my son and wife with a bottle of sparkling wine for a celebratory toast. The 23 days and 580 miles had not been without their challenges, but the experience had been unquestionably an extraordinary adventure.![]()

Phil Boyer retired in 2017 after working 38 years in R&D in the telecommunications industry. He now keeps busy building boats and teaching karate at two local clubs. Phil has been around boats his whole life, starting with paddling as a kid. At age 11 he built a sailing pram with a bit of help from his father. In 2006 he began building solo canoes and now has four of them, featured in the August 2019 issue. Phil’s interest turned to building his first solar-electric boat, SOL CANADA, in 2015.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Wonderful… both boat and adventure!! Would love to see the interior layout and set-up for overnighting, maybe another article 🙂

What a wonderfully interesting story and images.

Thank you!

from an expat Canadian living in Pittsburgh.

A very interesting boat design. Personally, I am considering building a solar-powered catamaran. However, in my project the floats will consist of modules so that the unit can be easily collected and reassembled.