In 1988, when Cindy, my wife then, and I were living in Silver Spring, Maryland, we took the lapstrake canoe I’d built to St. Michaels to paddle the Miles River, an estuarine tributary of Chesapeake Bay. I don’t recall now why we made the 80-mile drive there—we had other places to paddle much closer to home—but the sky was clear, and the water was lightly ruffled; it was a good day to be on the water. I like to go boating with a bit of formal style, so we flew the American flag at the stern of the canoe and my family’s house flag on a short staff at the bow. The design for the flag had been passed down from my third great-grandfather Charles Cunningham and his brother, Andrew. It was the private signal flown from the highest points on their fleet of ships, barks, and brigs carrying goods across the Atlantic. In the days before radio, the signals were the first things to rise above the horizon to let merchants know whose vessel would soon be in the harbor.

Christopher Cunningham collection

Christopher Cunningham collectionThere may have been something about my family’s house flag and my canoe that resonated with Judge North’s own 19th-century roots. His great-grandfather, who built ISLAND BIRD, was born in 1850, about the time the house flag was first flown by my third great-grandfather, and the lapstrake canoe I built was based on a design published by W. P. Stephens in 1889, in the same decade North’s great-grandfather was building boats.

Cindy and I paddled along the left bank of the Miles and hadn’t gone far when we rounded a blunt marshy point of land and neared a broad expanse of open land occupied by a lone, white, two-story house. A man in front of it was walking across the lawn toward us. The first thing he said was, “Is that a private signal?” It was the first, and still the only time, that anyone has recognized the flag for what it is. This was Judge John C. North, born into a family as steeped in boats as my own. When he invited us to come ashore, we pulled the canoe among the reeds and sat for a while on lawn chairs with Judge North and his wife, Ethel.

Photograph by Thomas H. Sewall, Collection of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum

Photograph by Thomas H. Sewall, Collection of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime MuseumThis photograph of ISLAND BIRD from the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum was taken by Thomas H. Sewell of St. Michaels in 1906 when the boat was already 24 years old. The pennant flying from the foremast, which says CHAMPION, was awarded to the season’s most successful racer.

The conversation turned to the boats he owned, which included two Chesapeake log canoes: 27′4″ ISLAND BIRD built in 1882 and 32′7″ ISLAND BLOSSOM built 1892. Both were built by his great-grandfather, William Sidney Covington, on Tilghman Island, just 8 miles to the southwest of the North home.

The Judge, as he is known locally, invited me to return to St. Michaels on a subsequent weekend to sail aboard ISLAND BIRD, the oldest and smallest of the roughly two dozen original log canoes that were still racing. Her hull was built of three logs joined side-by-side, then carved to shape; the sides are extended by means of fractional frames, patches, and carvel planks. North, along with his great-uncle, acquired ISLAND BIRD from a previous owner and restored her in 1949. He has been racing her every year ever since.

Morris Ellison

Morris EllisonMorris Ellison, who took the two contemporary photos of ISLAND BIRD here, is a sailmaker, now retired, who made sails for many of the old log canoes. He noted that the curved sprit booms were introduced around 1980 to allow the sails to take their best shapes on both tacks and that the “kite” was at its best working downwind. A log canoe could heel far enough to put the sails in contact with the water, a dangerous situation as the sails couldn’t be eased to spill the wind in a gust.

On race day, the Judge was, of course, ISLAND BIRD’s captain. I was one of four boardmen whose job was to shift hiking boards from side to side during tacks, set one end under the side deck, and scramble out on the other end—which was cantilevered over the water. Prior to the 1980s, the boards would have been hardwood 2 x 12s; very heavy, awkward, and dangerous to fling from one side of a log canoe to the other. Since then, they had been made as hollow box beams. While they were lighter, in the rush of coming about it was easy to bruise knuckles and bark shins.

I don’t remember much about the race and where ISLAND BIRD was in relation to the other boats. She was slender—just 5′6-1⁄2″ in the beam—and very sensitive to the position of the four boardmen so we were in almost constant motion. I was enthralled by ISLAND BIRD. It’s one thing to be in a sailboat going so fast that the water goes by in a green blur streaked white by the bow wave’s froth; it’s quite another to be perched on a plank, sitting fully outside of that boat, trying to come to grips with the notion that the boat I’m sailing on is over there.

Morris Ellison

Morris EllisonWith her slender hull and absence of a weighted keel, ISLAND BIRD has so little stability that she needs to be tightly secured at the dock to keep her masts from rolling her on her side. Underway, her stability is provided by boardmen on hiking boards. The larger canoes carried the tender for the mainsheet on the outrigger extending from the stern. ISLAND BIRD was too small to carry the extra weight that far aft and the outrigger was unoccupied. It’s very likely that Judge North is at the helm here.

Even though ISLAND BIRD was the smallest boat in the race fleet, she carried—and still does carry—so much sail that it was like sitting in the front row of a movie theater trying to take in the whole screen. The jib’s foot has a full-length club that pushes the tack well past the end of the bowsprit. The large foresail and the smaller mainsail have clubs at the ends of their sprit booms, vertically expanding what would ordinarily be the clew several feet in both directions. The main requires an outrigger on the stern to set the mainsheet block aft of the boom. ISLAND BIRD’s unstayed mainmast is 25′ tall; her foremast is 36′ tall and above it flies a “kite” topsail that looks like it could have been stolen from a Laser but for its silhouette of an osprey with a fish in its talons.

We were moving along at a good clip when we sailed into a sudden lull and ISLAND BIRD snapped upright. The hiking boards dropped suddenly and only three of us were able to scramble into the boat. The fourth boardman was flicked off his perch. The Judge looped the boat around and we picked up our AWOL crewman. As we chased after the fleet, one of the more experienced of the boardmen told me that losing someone off a hiking board almost always results in a capsize. Some of the larger boats, with four hiking boards and eight boardmen, have a better chance of surviving a man-overboard because the weight of one crewmember isn’t as significant as it is aboard ISLAND BIRD. We didn’t place well at the finish of the race, but it was enough of an achievement to have kept ISLAND BIRD on her feet.

I never would have imagined that the most exciting sailing I’ve ever done would be aboard a 106-year-old dugout canoe. And while I may never meet another boater who recognizes my house flag, with Judge North, one was enough.![]()

Chris, you never cease to amaze with your exploits. Another great bit.

I sailed on MAGIC, a heavy rival of the Judge, for a couple of years and could provide lots of info about the rig. We pioneered hollow wooden masts and hollow hiking boards and maybe hit the limit on mast length, which is controlled by the fact you can only have one set of spreaders. The mizzen, or as they call it, the main has to be a certain percentage of the main (fore). I graduated from board riding to “main” sheet tending on the outrigger to foresheet tender. We only used a 2×1 and working with the skipper had to time trimming, but we were more interested in how fast you could let the sail out than being able to trim under load. I only capsized MAGIC once.

The bitter end of that 2×1 foresheet was on a ‘biner that was hooked around horn of a cleat abaft the main, so the sheet had to get shifted each tack or jibe. Harken 2″ rachets were just coming on the market (late ’70s) and we used to blow up the ball bearings frequently, sent the blocks back for replacement under warranty. They finally asked what we were doing…now they have big boat blocks.

The real point of log canoes is that the boats are optimized for Force 1, 2, and 3. Takes under 10 to take them to hull speed which is what we get on the Chesapeake in summer. When it blew hard, we left the main on the beach, no jib, and a small fore, still crossing 4 boards, and carrying someone on the outrigger to help keep the boat from submarining.

Jibs, which have to be balanced at the 1/4 point, and the main really dictate where the boat wants to go. I used to trim the main when I was on the outrigger by watching Capt. Nasty (Jimmy Wilson) steering and slack or trim sheet to follow him. Jimmy’s brother ran the local Peterbuilt dealership and equipped us.

The Judge has done a nice book on log canoes.

“….trying to come to grips with the notion that the boat I’m sailing on is over there!” Priceless!!

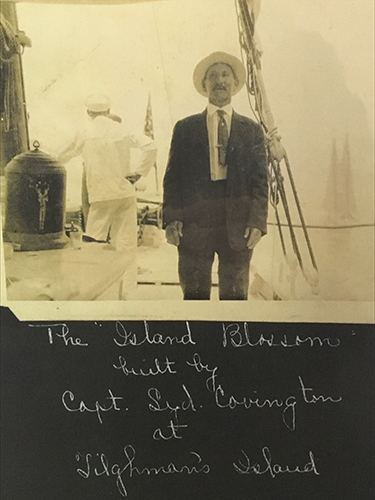

I enjoyed your article and thought that you might be interested in this picture of Capt. Syd. Covington.

He is my great great grandfather and a distant relative graciously shared this picture with me years ago. Notice ISLAND BLOSSOM in the background.

Laura Bobbin