Ron Rantilla’s Odyssey 165 is an unusual rowboat for touring and exercise. It is specifically for use with his FrontRower, a drop-in forward-facing rowing system. With the oars fully supported by the rowing rig, there’s no need to make the boat wide enough to provide a workable span for conventional oarlocks, or stout enough to take the strain of rowing on the gunwales. The Odyssey has the proportions of a canoe, offers the same view over the bow, and is similarly efficient converting effort into forward progress.

The FrontRower occupies a fair bit of space in the middle of the boat, but the ends have plenty of room for gear and I could easily imagine taking extended cruises. With one’s legs taking on the lion’s share of powering the oars, covering long distances with a heavily laden boat would save the hands, shoulders, and back wear and tear. There would also be a benefit in being able to keep the boat moving with legs alone while looking at charts or GPS, taking photos, and keeping well hydrated and fed.

photographs and video by the author

photographs and video by the authorEach oar comes apart at a joint just outboard of the hand grips, and it is easy enough to assemble and disassemble the oars while afloat.

Let’s take a look at the FrontRower. With all of its wooden struts and cords, it looks like a fancy trebuchet; it won’t hurl a rower out of the seat but it will hurl the rower and the boat forward. The inboard ends of the aluminum oar shafts are anchored to pivots at the top of the FrontRower. The brackets the shafts are mounted to bear against a slick plastic plate and the bolts holding the ends are pulled downward by springs underneath the plate. The arrangement holds the oar blades out of the water between strokes. Eyebolts on the looms are attached to cords that have springs at the other end that pull the oar blades forward during the recovery phase. Other attachment points are for handles to add arm power to the stroke. Attached to the handles are cords leading aft to pulleys, then forward to the swinging foot pedals. It all looks very complex, but it works like a charm.

Despite all of the moving parts in the FrontRower, the action is quite smooth and without any ticks, clicks, or apparent friction. The only sound it makes is the hum of braided line running through pulleys.

I’m quite particular about rowing style and wouldn’t expect a contraption like this to row with anything approaching elegance, but the FrontRower has beautiful blade work with the same grace and economy of effort as the Thames Waterman stroke I was taught by my father. The handgrips and the pedal cords are attached to the loom at an angle that brings the blades off the feather at the moment power is applied at the catch. The blades flip directly into the water without being squared beforehand. At the release, cords attached at an angle on the forward sides of the looms, rotate the blades while they are still immersed; the water moving past the blades helps rotate and lift them. It’s a lovely thing to watch.

The Odyssey is fastest with both arms and legs powering the stroke. The hands need to be used to speed the recovery.

At the finish of the stroke the blades come off the feather quickly and stay low. Note that the trim of the boat here is the same as it is at the catch.

The FrontRower can be powered by legs, arms, or both. Switching between arms and legs gives each set of muscles a break and all the while the boat keeps moving. Using both arms and legs doesn’t require any unusual coordination—it’s very much like rowing with a sliding seat—and like sliding-seat rowing, can really burn calories in a sprint. It’s a great full-body exercise.

The seat is adjustable to accommodate different leg lengths. Getting it set in the right position is critical. I started out with the seat too far forward and felt quite bunched up, especially with my arms, and unable to put on the power. Moving the seat back a few inches made a world of difference.

The padded seat and mesh backrest are quite comfortable and remained so for the duration of my morning outing. The backrest keeps the lower back in a fixed position, so my layback was limited to the range of motion of the shoulders and upper back, but the principal source of power comes from the legs, and the backrest is required to lock the hips in place. Restricting the layback minimizes the weight shift, a good thing for forward-facing rowing. With conventional rowing the weight shifts toward the bow during the layback at the end of the drive, and then when weight shifts toward the stern at the recovery, it pulls the boat forward. With forward-facing rowing the weight shift works the other way around, pulling the boat backward during the recovery. With the FrontRower the legs are engaged in rowing, and as they extend forward during the drive and layback, they nearly eliminate the effects of the upper-body weight shift.

The handgrips are padded and have snaphooks to clip into fittings on the looms. The grips are vertical and have plenty of play, so I could adjust their angle for comfort. It’s easier on the wrists to pull vertical grips than horizontal ones and with the FrontRower grips the wrists don’t have to bend constantly to follow the changing angle of the oar during the stroke. To back the oars, take hold of the looms directly at their padded grips. It’s easy to put the blades on and off the feather manually and hold or back water to maneuver in tight quarters.

At the catch the blades are close to the water and will come off the feather and bury themselves as soon as the pressure is applied at the beginning of the drive. Here the boat is being rowed with the feet only.

With my GPS recording speed, I rowed with my arms and logged 3 knots at a relaxed pace, 4 knots at an exercise pace, and peaked at 4-3/4 knots in a short sprint. Rowing with my legs I also did 3 knots at a relaxed pace, but that was the end of the legs-only trial. The springs that pull the oars through the recovery couldn’t work any faster. With both arms and legs powering the stroke (and the arms hastening the recovery), I clocked 4 knots at a relaxed pace, 5 knots at an exercise pace, and in a short sprint did 5.75 knots, beating the 5.36 knot hull speed listed on the Odyssey web page.

I had calm conditions while I was rowing the Odyssey, so I couldn’t evaluate how well the boat and rowing rig would take on wind and waves. The designer notes that his hulls “are great for flat water rivers, lakes, and bays, where they can handle reasonable chop and wakes from motor boats. They are not suitable for extreme conditions: whitewater rapids, heavy surf, breaking waves, high winds.” I’d agree with drawing the line at those challenging conditions. For very rough water I prefer sitting on a thwart to have my whole spine free to keep myself upright over a rolling boat, and having my hands on conventional oars so I can control where the blades are.

The greatest beam is not at the sheer, but at the chine below it, so a guard is added to protect the hull.

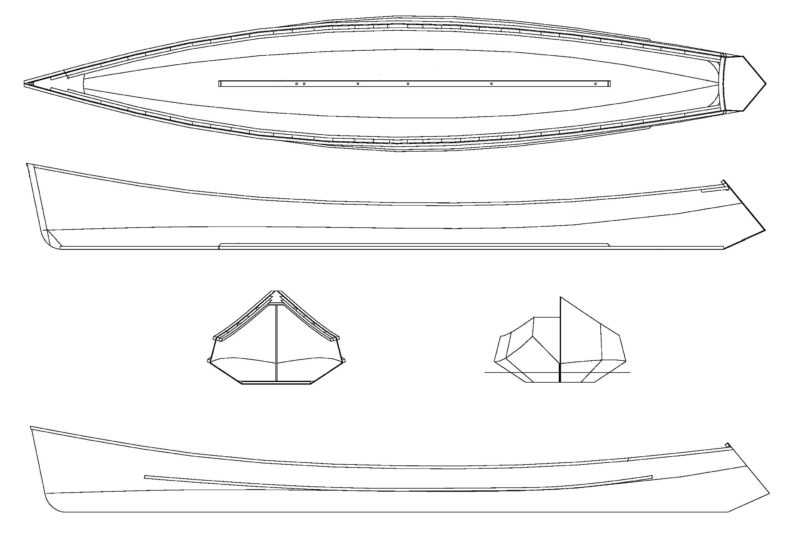

The Odyssey’s stitch-and-glue plywood hull has a flat bottom with no rocker. The bottom can be constructed from a single layer of plywood, or as a sandwich of plywood around a foam core. The foam core provides built-in flotation and stiffens the hull, making framing unnecessary. The lower planks flare outward above the waterline to provide stability. At the stern, they meet to give the hull a double-ended waterline below the reverse-rake transom. The sheerstrake has a pronounced tumblehome and provides clearance for the oars angling down from the apex of the FrontRower. The chine between the strakes has an unusual curve, rising upward at the stern but veering subtly downward to the bow, according to the designer, “following the wave curve.”

The plans provide full-sized patterns for the stem, breasthook, and quarter knees. Offsets are provided for the bottom and planks. The instructions cover making the foam-core bottom as well as the stitch-and-glue assembly of the rest of the hull. The kit includes all of the wooden parts for the boat, including plantation-grown okoume plywood in CNC router-cut panels with wavy finger-joints to align them accurately for full-length planks.

The Odyssey 165 and the FrontRower make an appealing combination of an easily driven hull and a powerful, ergonomic propulsion system, well suited for exercise, leisure days on the water, and extended cruising.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Odyssey 165 Particulars

[table]

Length/16′ 6″

Beam/35.5″

Depth amidships/12.5″

Height at bow/23″

Hull weight/approx. 60 lbs

[/table]

The Odyssey 165 is available as plans ($69), a kit ($1645), or a finished boat ($4945). The FrontRower ($2185) is available separately. The Odyssey 18 is a larger version that can be rowed solo or as a double.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

A neat set up. But I could not afford to buy and have the rowing rig shipped to New Zealand, having not having made fame and fortune in my earlier life. However, I am skilled enough to build the clever gear shown. Are there plans that can be purchased?

If you are looking for plans for the FrontRower rowing system, those are not available; it is sold as an assembled unit only. Shipping the rig to New Zealand by air is $400 USD. I agree this adds up to a lot of money, but “quality is remembered long after the price is forgotten.” Plans for the Odyssey 165 are $79 USD plus $35 shipping.

I built one of these a few years ago and absolutely love it! Rowing a dingy ashore now seems so strange with my back facing where I want to go. Ron’s kit has everything needed including concise instructions with photos. I love my early morning rows and being able to sip my tea without missing a stroke.

I purchased a FrontRower in September 2016 and have been using it every chance I get. Facing forward lets me navigate winding rivers and around obstacles. It’s fast and using it quickly becomes second nature. The whole unit is really well designed. It’s almost holistic. The legs drive the oars directly, eliminating stress on the back and wrists. The upper body is engaged only to the extent you wish. On the FrontRower, I have none of the wrist problems I suffer from when using my rowing machine. My previous experience was, well, zero. I’d never actually rowed on the water before. Since getting the FrontRower I’ve rowed an average of 3-5 days/week, on 23 lakes and four rivers, including multiple trips in the 20-25 mile range, and never felt worn out at the end of the day. Some day I’d like to try it in a faster boat—maybe Ron’s Odyssey or an Alden shel—but for now I’m content expanding my canoeing opportunities and discovering the joy of rowing.

I am wondering if the oar height above water is adjustable on the return stroke. I do my rowing on the open sound and it can get pretty choppy out and I frequently catch wave tops with my sliding-seat shell if I am not paying attention. By looking at the video it looks like the oars hover just above the water, if that height can’t be adjusted I’m afraid I would have very limited days I could go out. Any input welcomed. Also, if Mr. Rantilla is answering, I am wondering why you choose a reverse raked transom, is it just for looks or does is there some other reason?

For Tom Hesselink: Yes, you can lift the oars if needed, both on the return and drive. I can’t speak to rowing on the sound, but I can deal with the whitecaps on the lakes here in Minnesota. I more often lift on the drive to take shallow strokes in weed beds, shallows, and through light rapids.