LILLIAN HOWARD/WEST COAST ACTION PHOTOS

LILLIAN HOWARD/WEST COAST ACTION PHOTOSA sweeping sheerline, together with ample “rocker,” or bottom curvature, give the McKenzie drift boats the ability to deftly run whitewater such as Marten’s Rapids on the namesake river in central Oregon.

Marten’s Rapid on the McKenzie River in Oregon is a great example of a Pacific Northwest “technical” rapid. Running Marten’s requires quick moves, good judgment, and steady hands by the oarsman. Such rapids also demand the right kind of boat to navigate them safely. The drift boats that emerged on the McKenzie River are built to handle challenging whitewater and have become the boat of choice for Northwest river runners—particularly among fly fishermen pursuing trout in the upper stretches of these rivers where the drops are steep, boulders are common, and the water runs fast and cold.

These boats trace their heritage back to the early 1900s, when guides started taking fishermen down the McKenzie. The type evolved as legendary boatbuilders such as Tom Kaarhus, Woodie Hindman, Keith Steele, and others each put their own mark on the style. By the late 1950s, the McKenzie drift boat had pretty much reached its modern form, and its descendants continue to take fishermen places other boats can’t reach.

I’ve rowed a lot of guests through Marten’s Rapid in my handmade wooden boat. It is a perfect rapid to demonstrate how a McKenzie runs rapids safely while staying “relatively” dry. Its flat bottom has no vulnerable rudder or keel to resist lateral movement, allowing quick moves to avoid obstacles. Its extreme sheer permits the boat to dive down into holes and ride up the other side. Its flared sides keep water out when moving laterally or when splashing through steep drops. The exaggerated rocker, or fore-and-aft curvature of the bottom, lets the boat float like a leaf on the water and gives it high maneuverability. Take away any one of these characteristics, and a boat would probably capsize in a rapid such as Marten’s.

LILLIAN HOWARD/WEST COAST ACTION PHOTOS

LILLIAN HOWARD/WEST COAST ACTION PHOTOSIn drift boats, the oarsman rows facing the bow and downriver for a controlled descent of rapids. An anchor hangs off the transom for use in holding position while in calm stretches while fi shing.

Within the “family” of McKenzie boats, some are double-ended, others transom-sterned. Freeboard can be high or low. The right configuration depends on how the owner plans to use the boat and on which rivers.

Most professional guides prefer a relatively wide, transom-sterned McKenzie to carry ample gear and to give guests elbow-room for fi shing. Many boats are built with high sides and splash guards forward. The variations are heavily influenced by the favored river and the style of fi shing.

Thirty years ago, a variety of boatbuilders on the McKenzie River sold plans, kits, or finished boats. That is not so today, as wood has given way to fiberglass and especially aluminum. A few wooden boat shops still build drift boats and sell kits and plans, for example Mike Baker of Bend, Oregon (see www.bakerwood driftboats.com).

At the same time, interest in preserving the heritage of wooden drift boats has been renewed. Eagle Rock Lodge in Vida, Oregon, hosts a McKenzie River Wooden Boat Festival each April (see www.eaglerocklodge.com) drawing as many as 50 handcrafted drift boats. Owners and enthusiasts from all over the country share stories and admire the boats. A website (www.woodenboatpeople.com) keeps them connected, and a McKenzie River Drift Boat Museum is envisioned at Vida.

Many of the most traditional designs can be found in Roger Fletcher’s book, Drift Boats & River Dories (Stackpole Books, 2007; see a review in WoodenBoat No. 197 and his article about early drift boats in WoodenBoat No. 151). The book traces the history of the boats and the families that perfected them over the years.

GREG HATTEN

GREG HATTENMcKenzie drift boats are built to be able to handle whitewater, but they are all about fi shing. The author’s OBSESSION is neatly organized for one guide at the oars and a fl y fi sherman or two forward, and on its Baker Trailer Company trailer designed specifi cally for drift boats, it travels comfortably on remote dirt roads.

My boat, OBSESSION, is a traditional McKenzie-style drift boat that I built in my garage shop in 2004. One of my favorite rivers is the McKenzie itself, the birthplace of the type. The McKenzie has many Class II and III rapids and is home to one of the most beautiful strains of native redside rainbow trout in the West.

I chose five-ply marine-grade African sapele plywood about 1⁄4″ thick for the sides and seven-ply sapele about 1⁄2″ thick for the bottom. My frames are of Alaska yellow cedar, which contrasts with the dark plywood for a striking appearance. Sapele and yellow cedar are hard to come by in my area, and finding the right wood was my first lesson in boatbuilding patience. I used white oak for the chine logs, the gunwales, and the “dash,” the forward coaming that gives the fishermen something to lean against and blocks spray.

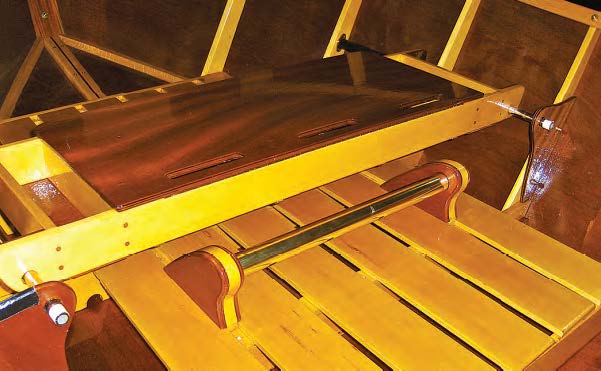

GREG HATTEN

GREG HATTENA section of brass tubing, recycled from an old barroom footrest, provides a stout foot brace when rowing in rapids.

The dimensions are pretty standard for a McKenzie: a little over 15′ LOA, with a beam of 6′ at the sheer and 4′ at the chine. Despite its small transom, the boat is considered a double-ender. I put a 1⁄4″-thick “shoe” of 1⁄4″ UHMW (ultra-high-molecular-weight) plastic on the bottom to protect the wood and to help the boat slide over rocks.

It took me more than 600 hours to build a boat that most guys could’ve built in half that time. I’m slow, my tools are old, I didn’t take a shop class in high school. I “redid” a few things I wasn’t happy with. For example, the stainless-steel screws I first used to fasten the mahogany sides didn’t look quite right, so I replaced every single one of them with brass. This boat challenged my patience, my creativity, and my woodworking ability. In the end, it was more about persistence and passion than skill.

GREG HATTEN, INSET: TIM HATTEN

GREG HATTEN, INSET: TIM HATTENSeats have built-in lockers to keep fishing gear dry and organized. Inset—When fishing, an angler stabilizes himself by leaning into a thigh brace on the aft coaming of the foredeck.

My boat was finally finished one morning when I ran out of things to put on a “to-do” list. Honestly, it kind of snuck up on me. When it was over, I missed the smell of fresh-cut wood, the first coat of varnish, the problem-solving, the orbital sander accompanied by Steely Dan. I missed going to the garage with my first cup of coffee in the morning to critique what I’d done the night before.

I missed all of it—until I put it in the water in the summer of 2004. Right away I had a new obsession, running rivers in a boat I built with my own hands. Moving with the water, flexing the oars on a deep pull, and hitting a perfect line through a rapid is a thrill. So is using the boat as an extension of the rod to move a fly on a graceful arc, enticing a steelhead to strike.

TIM HATTEN

TIM HATTENSteelhead trout are a favored quarry for fishermen—the author, in ths case—on Pacific Northwest rivers. Aboard OBSESSION, a first steelhead catch is an occasion for a celebratory fine cigar.

Right after launching, I learned that OBSESSION wasn’t really finished at all—which is one of the best things about wooden boats. The more I rowed and fished, the more improvements I thought of. My boatbuilding project entered a whole new phase.

When the rain settled in for the winter, I gathered my notes, doodles, and sketches of “boat applications” for OBSESSION. I picked through scraps of mahogany and yellow cedar, then happily went to work again. Using leather, I made a simple sling to hold the spare oar out of the way but ready for use. I made covers and drains for the gear compartments to keep fishing supplies dry, as well as drawers and better ways to keep things organized. After an incident in which an oarlock popped out along with its bushing and cotter pin, I made blocks of mahogany attached to the oarlock with an S-hook to prevent them from pulling through under stress. I also added tethers I like, made by Phantom Fire Pan and Oar Tethers in Estacada, Oregon.

GREG HATTEN

GREG HATTENThe stern-setting anchor makes it simple to stop at a promising fishing hole. The oars, which have substantial buttons to keep them from slipping out of the oarlocks, trail alongside, out of the way and ready for immediate use.

I have a “bar” on my boat. At a junkyard, I bought a 2′ piece of brass footrail of the type used in old barrooms, which I mounted to the floorboards as a footbrace. The wilder the rapid, the more I use the brace—it’s one of my favorite “boat apps” because it helps me to row out of danger. I have cup holders to keep cans and bottles in place, along with the occasional cigar that gets lit up when a fisherman celebrates his first steelhead catch. I bought rubber mats of the type used in restaurant kitchens and cut them to fit the floor to protect the wood and provide springy comfort for fishermen who stand up almost all day.

GREG HATTEN

GREG HATTENDory-style construction relies on a flat bottom and straight sides of plywood, making drift boats comparatively simple to build.

Oars can take a beating on dirt-road rides to the river, so I built holders to keep them from banging around. I can also padlock them in place while leaving the boat unattended to shuttle gear. With a bracket made of sapele and yellow cedar, the oars also make a handy tripod where we can hang a 1962 Coleman lantern at camp.

Fly-rod holders are essential because your hands are on the oars all day. I’ve caught hundreds of steelhead with a setup I created using bamboo, sapele, yellow cedar, and a leather strap. When we run particularly challenging rapids, my guests need both hands free to hold on, bail, snap a picture, or tighten their life jackets, so I built a couple of simple rod holders behind their thwart. As soon as we clear the rapid, they can return to fishing immediately.

One removable floorboard doubles as a cutting board to take ashore when it’s time to clean fish, and another doubles as an onboard table.

GREG HATTEN

GREG HATTENWooden construction also makes boats comparatively easy to repair. After an encounter with a rock, the author used bolts (later cut off flush) to clamp an epoxy repair. The stitched-together wound left an honorable “scar.”

The most sickening sound in the middle of a rapid is a dull thud like a sledgehammer hitting the bottom, followed by wood splitting. I’ve heard it. It hurts. A lot. My first thought is never about the repair, it’s always sorrow that I hurt my boat again and disappointment that I didn’t avoid it. But in reality, when you row on Class II and III rivers, you’re eventually going to hit a rock. I remind myself again that I built this boat to run rivers, not the garage.

I use epoxy with fillers for repairs, sometimes augmented by fiberglass cloth or even a plywood backing plate if the break is bad. Normally my repairs are as smooth as glass. To fix one bad 1′-long slice, I used brass machine screws with wing nuts through blocks of wood to bring the plywood fair. After the epoxy set, I cut the screws off flush, which showed through the varnish later, like stitches in a wound. The result was a subtle scar—the mark of a boat with character and experience, one that has been somewhere and has stories to tell.

RANDY DERSHAM

RANDY DERSHAMA wooden drift boat seems to correspond particularly well with the outdoor lifestyle of the Pacific Northwest, here on the Snake river with the Grand Tetons beyond.

This boat will continue to collect stories and scars as I row the rocky Northwest rivers. I’m told my OBSESSION is perfectly named—and I couldn’t agree more.

For more on McKenzie River drift boats, see Roger Fletcher’s book Drift Boats & River Dories (Stackpole Books, 2007) and his website.

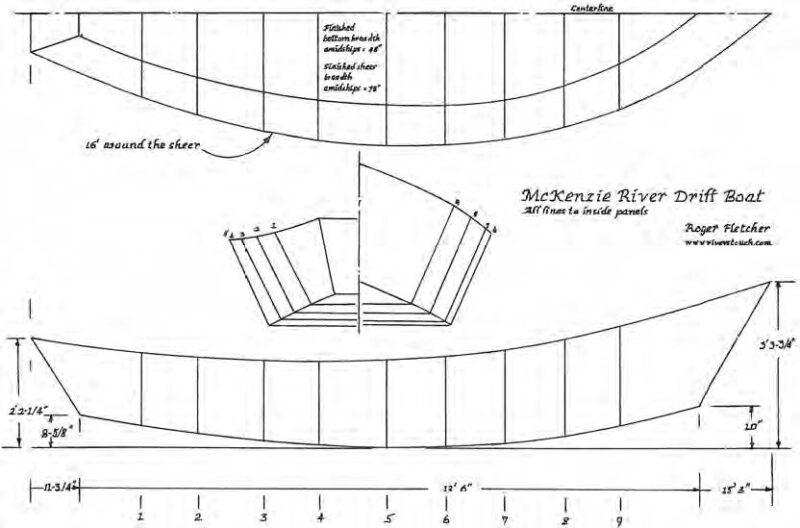

ROGER FLETCHER

ROGER FLETCHERThe design the author used to build OBSESSION was by a company no longer in business. Roger Fletcher, author of Drift Boats & River Dories, has drawn a very similar hull, a type known as a transom-sterned double-ender. His book has details and plans for a wide variety of drift boats, plus details of construction and use, with drawings by veteran WoodenBoat illustrator Sam Manning.

Particulars:

LOA 15’3″

Beam at shear 6’6″

Beam at chine 4′

Draft not much

Glad to see an article about this boat style. The McKenzie river is named after my several gŕeats uncle Donald.

When I first saw articles about these boats (probably in How to Build 20 Boats) over 50 years ago, they were photographed going downriver stern first, with the rower facing aft to control the drop and maneuver around boulders, with the sharp bow facing upstream splitting the current. That looked like a proper way to do it. So I’m wondering what the reasoning is for going down bow first.

Thank you for the excellent story. I row wooden racing shells (Pocock, Owen, G. King). There is nothing like wood for making peace-on-water.

Best regards,

Don Costello

Coos Bay, OR

Me again: I hope you meant you used bronze screws, not brass. Brass fastenings have a poor reputation amongst boat builders for two reasons: 1) It’s a weak metal, very easy to twist off when driving screws into difficult woods; 2) the zinc/copper combination sets up self-electrolysis over time, with the zinc vanishing, leaving a weak porous copper behind.