Although I had owned boats from 10′ to 34′ and captained boats up to 74’, I had never built one. I had experience fixing boats—mostly fiberglass repair, paint, gelcoat—and one day, I decided I was going to build. I began by researching designs and building techniques. Low maintenance and low cost of operation were my top priorities, followed by comfort, seaworthiness, and appearance. There were many designs that caught my eye, but I kept coming back to B&B Yacht Designs. Their boats all appeared to be well-thought-out, practical designs and not just something arbitrarily drawn in a computer program. It was clear to me that designer Graham Byrnes understood the dynamics and build-ability of wooden boats.

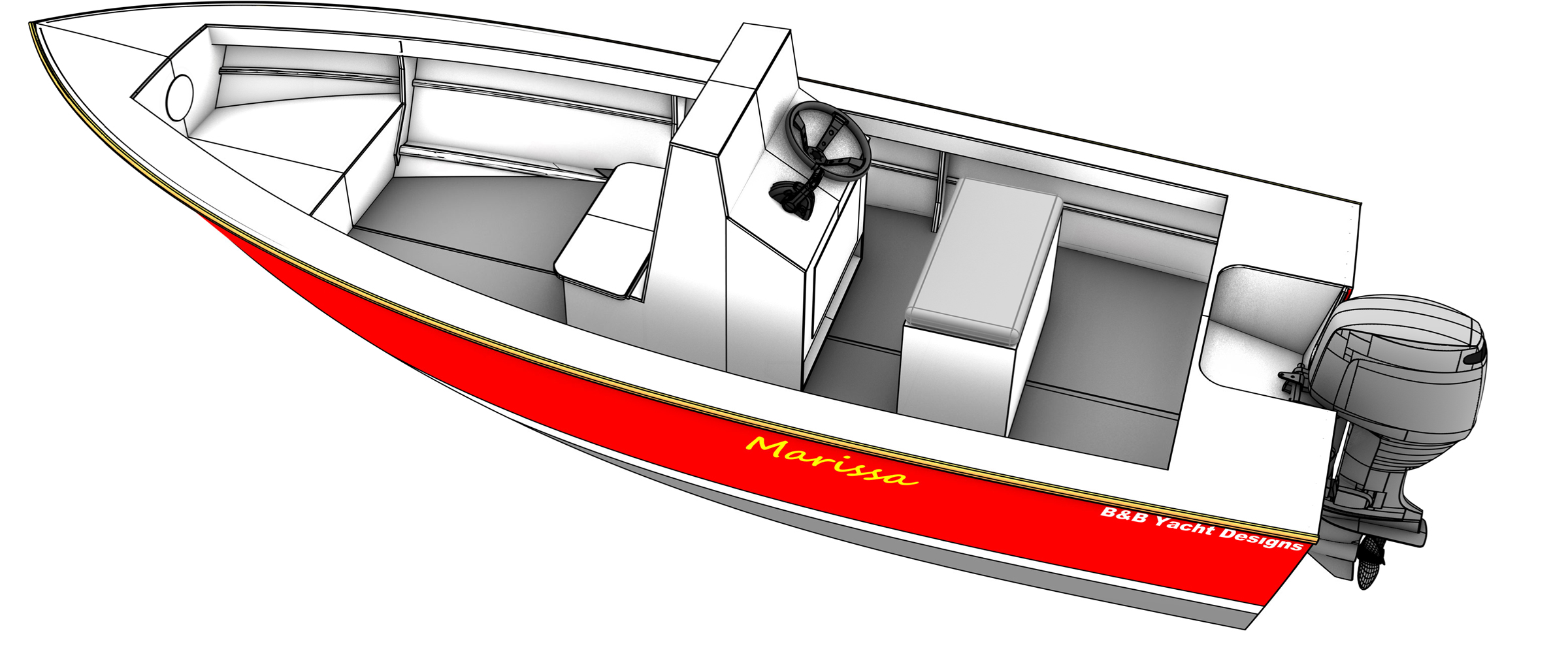

I came across an article in WoodenBoat No. 211, listing the five finalists in a design contest titled, “The Pursuit of Pleasure at Two Gallons per Hour.” The winner was Graham’s Marissa 18, an 18′ center-console skiff built in plywood. It was visually appealing and looked like it would be efficient, consuming just 2 gallons of fuel per hour and seaworthy enough for me to feel safe in 2′ to 3′ chop.

I contacted B&B Yacht Designs and purchased the CNC-cut kit. I went with the kit instead of building from the plans, not only for CNC accuracy but also to save time, as I would have a limited amount of it to complete the project.

When I drove to the B&B shop in Vandemere, North Carolina, to pick up the kit, I had a chance to meet with Graham and take a look at a finished Marissa. He was extremely helpful and answered the multitude of questions that can come from someone who has never built a boat before. He asked me what motor I planned on installing. When I told him it would be an Evinrude 60-hp E-TEC, he recommended moving the console forward as well as adding an extra layer of fiberglass, or starting the sheathing with a heavier single layer on the bottom. With such a powerful motor, at the top end of the recommended range of horsepower, the boat could be subject to heavy impacts while taking chop at top speed.

Trey Williams

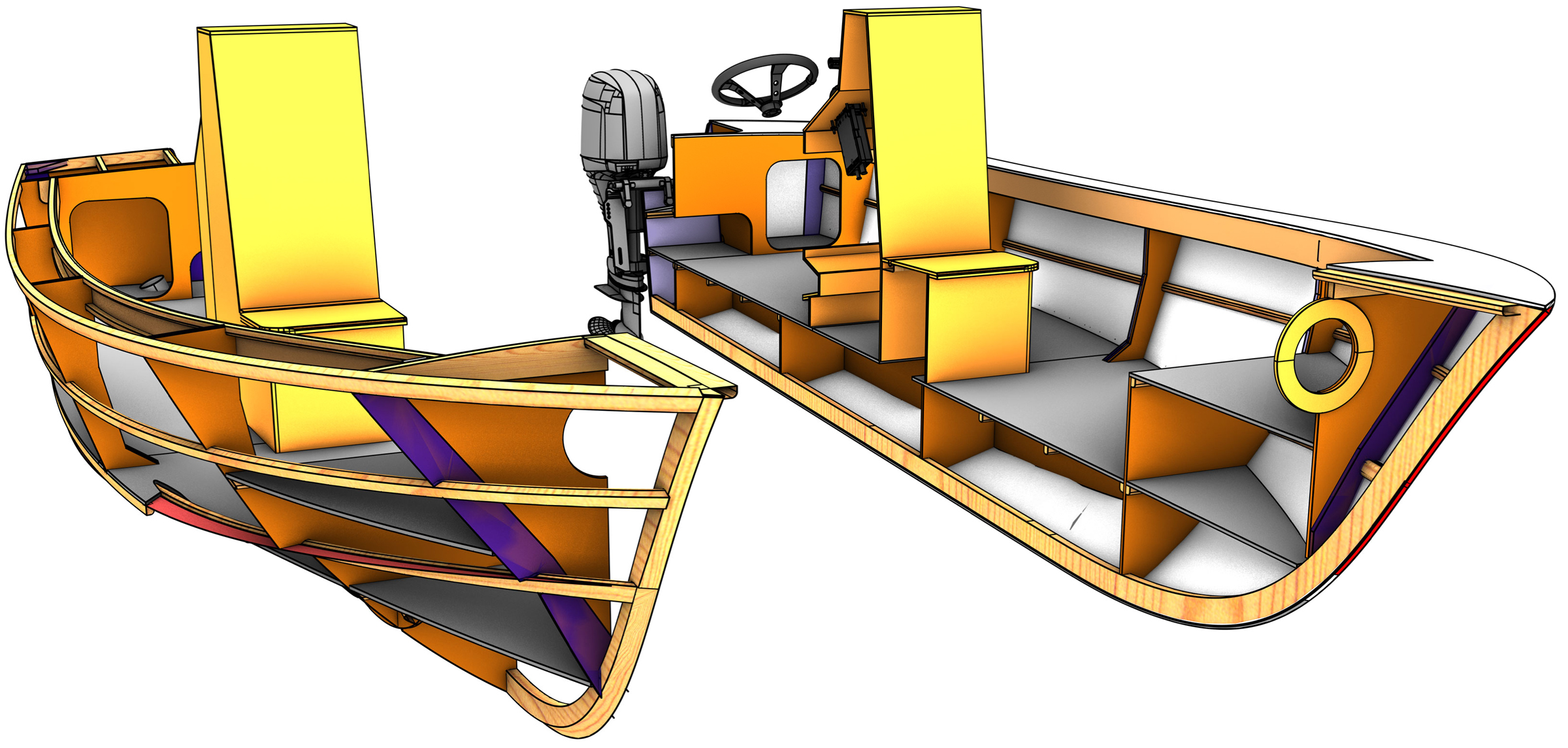

Trey WilliamsThe egg-crate construction of the frames, stringers, and cockpit sole provides a solid base to build the hull on.

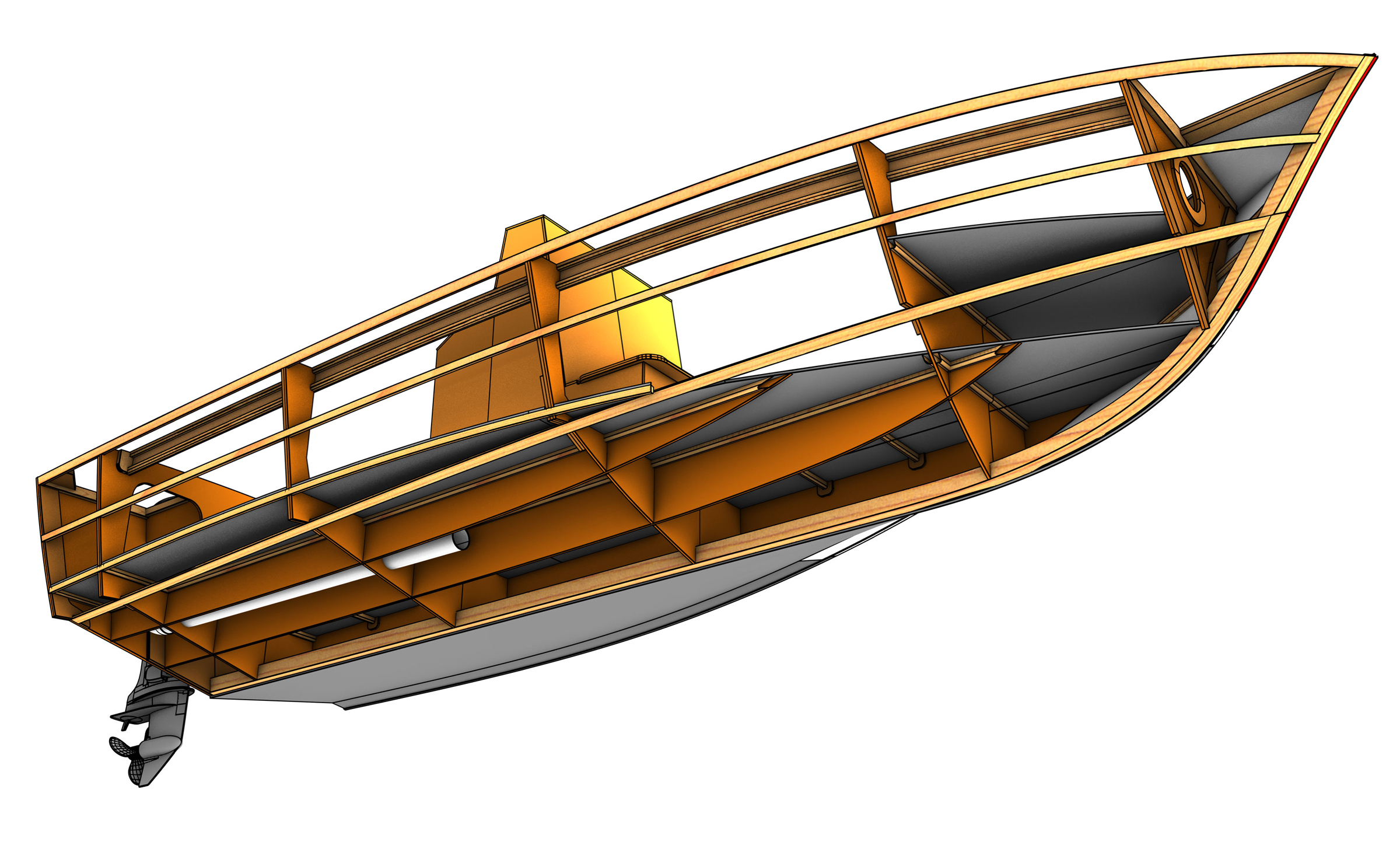

The plywood pieces in the kit are all high-quality BS1088 okoume, and the additional lumber, purchased separately, is straight-grained, knot-free southern yellow pine. Each side, bottom, and chine-flat panel is assembled from three pieces with precision-cut finger joints. The boat is built on a jig that uses the cockpit sole and an egg-crate grid of the frames and stringers that support it. The build is a bit different than a traditional strongback-and-mold setup; the sole rests on sawhorses and supports the three frames, two bulkheads and the stem, eliminating the need for any further temporary support structure. The hull side and bottom panels get glued and screwed to the transom, bulkheads, and stem and, after the epoxy cures, all screws are removed.

The build went as expected—exceptionally smoothly. All panels bent home exactly where they should have; I believe this is a result of the thoughtful design. After I assembled the hull, it ended up being remarkably fair.

I ended up moving the console forward 8” on both Graham’s recommendation and my own preference. I’ve had no problems with the way it is now, but if I were to do it again, I would consider moving it an additional 2” to 4”, just to have more cockpit space in the stern. After sea trials and much consideration on whether to sit or stand at the console, I opted to stand—it feels more natural to me and offers better visibility than sitting. I purchased an aluminum leaning post with built-in storage and rod holders. It is the perfect width for me and almost seems as if it were custom-made for the boat. It has space underneath to store a cooler and a pad on top for an elevated seat.

Also on Graham’s recommendation, I used heavy 1208 biaxial ’glass on the inside of the hull, bulkheads, and stringers—instead of just giving them a coat of epoxy to seal them. On the outside, I put 10-oz ’glass over a reinforcing layer of 1208 on the keel and chines.

Trey Williams

Trey WilliamsThe chine flats are an effective means for keeping spray from getting into the boat when it’s on a plane.

After fairing, priming and painting, it was time to outfit and rig the boat. I installed hydraulic steering for the 60-hp Evinrude E-Tec. It was more expensive than a cable system but well worth it for the smoother feel and minimal steering effort. Finding the right prop took some time since the boat is relatively light compared to fiberglass production boats and the 60-hp E-Tec has a larger gear case and lower gear ratio.

Once everything was installed it was time to have the predelivery checks done on the motor and rigging and to see if it was watertight. I have the Marissa on an aluminum torsion-axle trailer with bunks cut to match hull rocker for full support. It tows with no issues and is easily launched and retrieved singlehanded.

Trey Williams

Trey WilliamsThe author, preferring to stand at the helm rather than sit, equipped his Marissa with a so-called post to lean against.

The moment of truth came when the Marissa went into the water for the first time and sat exactly where the plans specified. Stability is good, but if two large adults stand on the same side, the hull will lean quite a bit; that is expected given the beam and the deadrise at the transom. After a few trips, dialing things in and getting used to actually being in a boat that I put together, it was time to move from a calm river and the Intracoastal Waterway to some more open water. My experience of crossing boat wakes gave me high hopes for the Marissa in some real waves. Once I got out in some light chop in open water, my hopes turned out to be well founded. The Marissa really did perform as expected. It cut through the waves at any angle, and the water is thrown down and away by the generous chine flats.

Courtesy of B & B Yacht Design

Courtesy of B & B Yacht DesignThe Marissa is designed to take outboards from 25 hp to 60 hp. The boat here is running a 40hp motor.

The boat handles beautifully in most anything I’m comfortable taking on in an 18’ boat. It turns exceptionally well when I’m cruising winding rivers, and on hard turns at speed the boat just locks in and corners like it’s on rails. The first real trip I took was down and across North Carolina’s Currituck Sound, where it can be a slick calm one minute and steep chop the next. On the outbound crossing, the Sound was nice and calm, and the Marissa cruised easily at 20 knots burning just over 2 gallons of gas per hour. The return trip was a little different. The afternoon sea breeze had kicked up 2′ to 3′ chop, as it typically does in the summer. I didn’t know what to expect, but I wasn’t too concerned since I was pretty confident in the Marissa’s abilities. I thought it was a good test and yet it was a pleasingly uneventful return trip. With the boat cruising at 20 knots, the water just split and went down and out, no pounding of any sort (but that was expected as it was a following sea). Once I was farther from shore and among the largest waves it was time to see how it handled different angles. I was most surprised to see that the best angle was straight into the waves. They just split at the bow and were pushed away and down. Taking them on a bow quarter at 20 knots was a bit much for me. The ride wasn’t at all jarring, but there was a bit more movement than would be comfortable to me for long periods. Slowing to 15 to 17 knots, the excess movement head-on is almost gone.

Courtesy of B & B Yacht Design

Courtesy of B & B Yacht DesignThis Marissa 18 is outfitted with a seat instead of a post

The boat stayed remarkably dry in all angles to the waves. The only times I’ve noticed spray coming over the sides have been when the wind is at least 15 mph and on the beam and, even then, just a small amount would occasionally blow up. Overall, I think the Marissa is one of the driest boats of any size that I’ve owned. I can just squeeze out a top speed of 30 knots with only myself aboard and I feel that’s plenty fast. I spend most of my time cruising 4,000 to 4,500 rpm at about 19 to 23 knots and burning 2 to 2.5 gallons per hour, depending on how many people are aboard. An all-day fishing trip burns just 5 to 7 gallons of gas.

Courtesy of B & B Yacht Design

Courtesy of B & B Yacht DesignThe seat built into the center console provides a good place for a passenger without obscuring the view forward from the helm.

So far, I’ve taken my Marissa from lower Chesapeake Bay down to Stuart, Florida, and a few places in between. Typically used in the lower Chesapeake Bay and Currituck, Albemarle, and Pamlico sounds, the skiff does exactly what I expected and even more.

The boat is well suited to my uses and perfect for my home waters. I smile every time I get aboard. I appreciate the performance and the affordability of operation, and enjoy the feeling of operating a boat that I built. I think a Marissa can be built by most anyone with a general understanding of working with wood, epoxy, and fiberglass. If you’re looking for a design that is efficient, looks good, and is safe and comfortable, this is a great option. I plan on building another, slightly larger, B&B design in the future to get back into fishing bigger waters and offshore.![]()

The first boat Trey Williams learned to operate was a plywood skiff his grandfather had powered by an Evinrude 18-hp outboard on the Currituck Sound in North Carolina. He purchased his first boat, a 14’ flat-bottomed aluminum johnboat, before he could legally drive a car. Many boats came and went after that, eventually leading to getting his 100-ton masters license and running large boats for a few years. He doesn’t foresee a time when he doesn’t have some kind of boat. He lives in southeast Virginia and has his pick of many bodies of water within a short distance from home.

Marissa 18 Particulars

[table]

Length/18′ 0″

Load waterline/15′ 3″

Beam/6′ 10″

Draft/8.75″

Horsepower/25 to 60

Displacement/1680 lbs

[/table]

B&B Yacht Designs offers the Marissa 18 plans, with full-sized Mylar templates, in either metric or imperial, for $260. A kit of CNC-cut plywood parts and the required solid wood for the stem and keel is available for $3,620. Additional kits for epoxy and hardware are also available.

Editor’s note: We published a previous review of the Marissa 18 in Small Boats 2011. It was written by WoodenBoat Senior Editor, Tom Jackson, after Graham Byrnes paid a visit to the WoodenBoat waterfront with his Marissa 18. In the review here, Trey Williams provides his perspective as a builder and owner of a Marissa 18.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

In the end, how much did it cost w/o engine? How long did it take you? Thanks!

I had my Marissa built from a kit with the forward deck coming back past the second frame and fitted with a varnished curved coaming around. I intended the boat to be built Bristol fashion but, on a handshake sort of contract, the builder had a more yacht-like vision which added a fair amount of extra weight. Only mistake in the build was installing two hatches in the floor deck forward and aft which leak rainwater. This required me add a bilge pump. The boat with a 50-HP Honda maxes out at 27 knots/5400 rpm. But the sweet spot is 18to 20 knots. Found a dolphin on the cavitation plate helps the boat get on plane quicker and stay there at lower speeds when crossing boat wakes. Boat performs as indicated in Trey’s write-up. Great boat, but does require some extra time at launching ramps around the Chesapeake because of the attention and questions.

I have something somewhat similar but with a cabin and very small “emergency” sleeping cuddy. I think it is a Crocker, but not sure. A complete restoration made this a nice boat and was solid wood/fiberglass built in the ’70s/’80s. Heavy use in Alaska shows the usefulness of this classic design. This boat is very light and expect at least 2 miles per gallon or less.