Jack Crawford

Jack CrawfordThis classic view of a Marblehead gunning dory shows the type as it was originally intended to be used. The boat, a copy of REPUBLICAN, shows her elegant sheer and lovely stern.

John Gardner wrote about Will Chamberlain’s Marblehead gunning dories for several magazines and books. Each version revealed a little more about the boat’s history and qualities. Designed for gunning the ledges for sea ducks during New England’s early winter, the Marblehead gunning dory had to be rugged. It also had to be lightweight, so that once you had rowed out to where the ducks were, you could pull the boat onto the ledges.

The boat that originally captured John Gardner’s attention was sitting on Marblehead’s Barnegat beach in 1942. Built by Will Chamberlain, it was the “ultimate dory,” in Gardner’s view, a boat that for “rough water ability, easy performance under oars, respectable speed and capacity, capped by handsome appearance…is one of a kind.” My personal experience, along with that of others who know the boat well, hasn’t proven otherwise.

As a young(er) boatbuilder, I pored over Gardner’s drawings and text. When I first tried to build boats “professionally” on my own, the Marblehead gunning dory was nearly the first boat I built. When Gardner’s book Wooden Boats to Build and Use came out in 1996 and I saw the 17-footer, I felt I had found the right version of the boat. That boat, REPUBLICAN, had been built by Capt. Gerald Smith to lines drawn by his good friend Walter Wales, who later built INDEPENDENT, an 18′ version. Both of these boats are in active use almost 50 and 40 years after they were built.

I run the Alexander Seaport Foundation in Alexandria, Virginia. In 1998, we built a glued-lapstrake plywood rowing version of the boat, from setup through getting the boat ready for paint, as part of one of our weeklong classes. The combination of dory design and plywood construction allows it to be built simply and quickly. With an extra wide garboard, it takes only three strakes per side. The frames on our boat are laminated Douglas-fir overlapped at the center, just like the original boat’s “grown” frames. The frames also serve as the building molds. It’s a boat that almost builds itself.

When Walter Rissmeyer called a few months later, I knew this was the boat for his project, Potomac Adventure. Walter worked for the local public TV and radio entity. He and producer partner Joe Brunzak had planned to travel the entire length of the Potomac River. The first 100 miles, from the Fairfax Stone, in western Maryland, to Washington, D.C., were to be done on bicycle. Then they planned to canoe the 10 miles from D.C. to Alexandria. The remaining 100 or so miles were going to be accomplished by a more substantial boat.

South of Washington, the Potomac just gets wider and wider. It’s shallow and is prone to nasty storms with vicious chop. It’s also tidal, even up by Alexandria, where the water is still fresh.

To take advantage of the winds and tides, Walter and Joe needed a boat that could either be rowed or sailed. They needed a boat that could carry all their gear for a weeklong trip, and one that was big enough for them to sleep in, if necessary. Most important, they needed a boat that could stand up to the weather that would probably come their way. They ended up with our dory, which they named BEANS AND CORNBREAD.

The first leg of the dory trip from Alexandria to Quantico, Virginia (about 20 miles), proved that the boat rows well. When I talked to Walter Rissmeyer about his trip, nine years later, he and I both remembered the same story about the boat’s seaworthiness. The day after leaving Quantico, they had to make the largest bend in the river, located above the Route 301 bridge. It’s a several mile fetch. The wind was blowing over 15 knots and right on their nose. It took Walter and Joe most of the day, taking turns rowing, to work their way to the bend. Halfway there, they noticed that they were being overtaken by something that looked like a mini Loch Ness monster swimming in the water. It turned out to be a deer. The deer reached shore before the boat. Not to be outdone by a deer, Walter and Joe set sail. The wind came on their beam and they covered a distance equal to that they had just rowed—in under an hour.

The next day it blew even harder. When Walter and Joe rowed into a marina at the end of that day, the folks in a 20′ center-console outboard couldn’t believe that they had been out on the river.

We had built BEANS AND CORNBREAD as a rowboat, but it needed to sail too. We didn’t use Walter Wales’s rig as shown in Wooden Boats to Build and Use. Instead, we put a 55-sq-ft Chesapeake sprit rig into her because that’s what we happened to have lying around. We used a Scandinavian push-pull tiller to steer. With this rig, a long pole pushes, or pulls, a short, one-armed yoke that’s attached to the top of the rudder. It was a last-minute deal, typical of “on-demand boatbuilding.” Walter and Joe had to finish building the oars for that trip down to Quantico.

Jack Crawford

Jack CrawfordUnder sail, the Marblehead gunning dory is both fast and responsive. Although this version shows a rudder being used, generally they were steered with an oar over the lee rail. The spritsail rig shown provides fast sailing in light airs. The old gunners would have used a much smaller “leg-o’mutton” sail to help them along in the winter when “gunning the ledges.”

The return trip demonstrated a little-known feature of the design (and for safety’s sake, it probably should remain that way). In a pinch, the boat can be cartopped on a small car. Walter called me when they had reached Point Lookout at the mouth of the river. I had offered to pick him up, but for some reason I didn’t have a trailer available. Roof rack extensions on my trusty Geo Prism did the trick. It looked strange, but the rig worked. It only became slightly unstable when Walter, Joe, and all their gear got out of the car. Once I dropped them off, I had to take the turns a bit slower….

Walter and Joe’s experience proved the boat’s worth as a camp-cruiser. It built friendships and relationships. Walter and Joe are now partners in an Emmy Award– winning video production company. After the trip, Walter liked BEANS AND CORNBREAD so much he took her home.

I’ve gotten to know one more of these boats. This one came into my shop when its owner, Steve Jones, a naval architect and wooden boat aficionado, moved to the area and started volunteering at the Seaport Foundation. It turns out that Steve’s boat is the old INDEPENDENT (now renamed ALLELUHIA)— the boat that Walter Wales built in 1970 and the one shown in John Gardner’s last book. Wales built the boat traditionally, in Marblehead, using Gerald Smith’s set of original Chamberlain molds. He lengthened her to 18′ (Gerald Smith built REPUBLICAN at 17′ because that was the length of his available planking stock). INDEPENDENT was originally used for her designed purpose, to go gunning on the ledges around Marblehead. He reports that he put in a daggerboard so that he could say he could sail her. He also used her for occasional overnight camping trips.

After Wales gave up hunting, he donated INDEPENDENT to Bobby Ives, that wonderful minister who runs The Carpenter’s Boatshop in Pemaquid, Maine. Bobby used the boat as transport for his ministerial duties out to the islands in Muscongus Bay. Then, in 2005, INDEPENDENT came to Steve Jones.

Steve uses the boat year round and, so far, only for day trips. Most folks would row the Marblehead gunning dory more than they’d sail it. This isn’t a boat that’s going to beat to windward against a Lightning. If you want to head straight into the wind, use the oars. Walter Rissmeyer feels that he was able to point up to 45 degrees under sail. Steve Jones doesn’t like to sail any closer than 90 degrees to the wind. A lot depends on how the boat is rigged and what the centerboard and rudder look like.

Everyone I know who is familiar with the Marblehead gunning dory loves it. It certainly seems to be, as John Gardner says, the “ultimate embodiment of that perfection of form and function attained by traditional small craft in the final years of the 19th century.” When summing up his trip in BEANS AND CORNBREAD, Walter Rissmeyer said, “The boat swam. It didn’t pound, or slap. It swam through the water.” That’s a pretty good recommendation for any boat.

Plans for the Marblehead gunning dory are found in John Gardner’s book, Wooden Boats to Build and Use (Mystic Seaport Museum, 1996).

Walter Wales

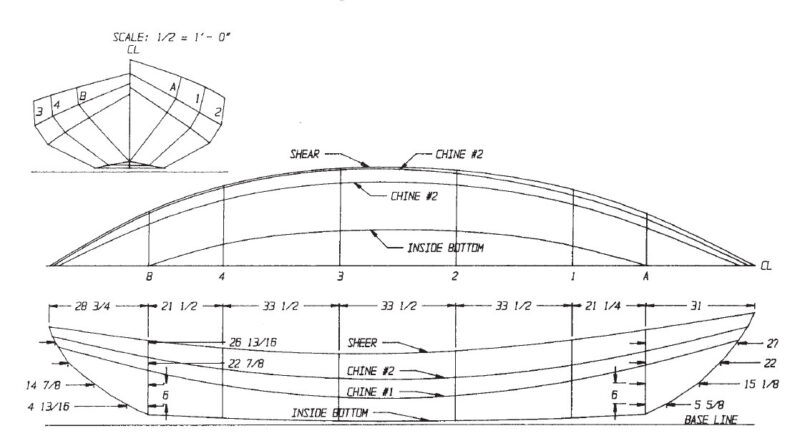

Walter WalesThe lines of the REPUBLICAN indicate why John Gardner called the Marblehead gunning dory “the Queen of all Dories.” The sweeping sheer, balanced ends, narrow bottom, and almost round sides combine to produce a boat that is fast under oars, seakindly, and lovely to look at.

My only cavil about this article is that the opening photo shows oars that are too short for the beam of the boat. I suspect they would have made better progress at the bend with the right oars.

I disagree, however, with calling the design “ultimate,” as both Whitehalls and Adirondack guideboats are quite seaworthy under oars and sail. I have used both in rough water conditions and as safety boats for events.