Kelley Webster

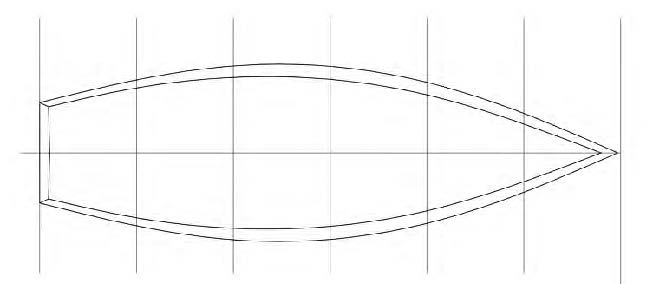

Kelley WebsterFor the design of MALU, Michael Jones was inspired by Clark Mills’s popular Windmill design. Mills was an early mentor to the designer.

Back in 1926, before hurricanes had names, a big one struck Miami. The storm surge drowned 200 people and deposited fine yachts, commercial vessels, and a five-masted schooner in city streets. What came to be called The Great Miami Hurricane then swirled across Florida. On the Gulf Coast, the winds uprooted many tin signs advertising real estate. That storm put an end to Florida’s latest land boom and scattered those “For Sale” signs far and wide. An 11-year-old boy discovered some of them, rolled and battered, in the woods near his Clearwater house. That’s how Clark Mills got his start building boats.

“Clark found,” wrote Florida boatbuilder Tom Mayers, “that if he carefully straightened the sheets of metal out and used wood supports at the seams, a child with the tin, wood strips, nails, and a little roofing tar could make a small rectangular boat that floated.”

Years later, when he was 32 years old in 1947, Clark Mills designed another rectangular boat. This one was plywood, and it was intended for a new youth sailing program begun by the Clearwater Optimist Club. “I really didn’t progress much in my design, did I?” the ever self-effacing Mills said to Mayers. The Optimist Pram eventually became an international class, and a half million are estimated to have been built thus far. But, created for kids 8 to 15 years old, the Optimist raised an obvious question. What would young sailors graduate to when they outgrew the Opti?

The answer emerged in 1953 in the form of a speedy, V-bottomed one-design, intended, Mills said, “to be the leanest, meanest, go-to-hell sailboat [the kids] could get.” At 15′ 6″, the plywood boat was less expensive to build than a like-sized, plank-on-frame Snipe. What’s more, Mills developed it with economical, amateur construction in mind. He called his design the Windmill. “It was just the dad-gumdest boat that ever I was in,” a local skipper and boatbuilder known as Captain Cherokee told Mills after trouncing a variety of established classes at a race.

Kelley Webster

Kelley WebsterMALU is meant to be less demanding to sail than the Windmill. The new boat has a springier sheer and a straight stem—traits borrowed from working sharpies.

Tarpon Springs, about 17 miles up the road from Clearwater, is where Michael Jones grew up during the 1960s. There was a vibrant wooden-boat world in that part of Florida then. The city’s Greek sponge fishermen were still using adzes and hand tools to build their vessels. Ten miles south of Tarpon Springs lived the Sage of Dunedin, John Hanna, designer of the famed Tahiti ketch. Drawn to boats, Jones became a Sea Scout. He learned to caulk, repaired an old 10′ dinghy, and sailed into the Gulf of Mexico until Florida was out of sight. He crewed on a speedy Windmill and worked on a fishing boat. One day a friend showed him a copy of Howard Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft. “That did it,” Jones said. “I was on the road to ruin.”

During his college years, Jones worked part-time in construction and later built homes together with a partner. He made good money but missed the road to ruin. “I told my partner I wanted out,” he remembered. “In 1979, I traded a piece of property for a 37′ Geiger-designed yawl and moved aboard. One day, I met a guy I’d built a house for. He asked me to go to Antigua and oversee the Starling Burgess–designed 10-Meter yacht he owned.” Jones’s success with the 10-Meter led to another project, and then more.

In 1981, Jones followed his road to a job at Clear water Bay Marine Ways, home to Clark Mills Boatbuilding. That’s how Jones got to know “Clarkie.” “He became,” said Jones of Clark Mills, “a great friend and mentor. We would sit in his drafting room and look at his half models, and he would tell stories.” These days, Jones works independently on a variety of high-end projects. His desire for a new small boat resulted in the craft featured here. He considered a variety of traditional flat-bottomed sailing skiffs and sharpies before turning to plans he had for the Windmill.

“The V-bottom,” concluded Jones, “makes better structural sense and a better, or at least faster sailing boat when heeled. I knew from experience that it would be a fast bottom. The other consideration was time. The plywood V-bottomed hull will go together quickly, compared to the planked hulls I’d been considering.” Still, Jones understood that the lean, mean Windmill would need modification to suit his needs. “The boat was too quick for my purpose. It wasn’t something non-sailing friends would enjoy, but it did have a connection to the local waters and my past.”

Michael Jones

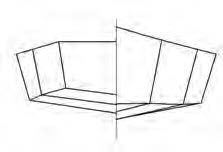

Michael JonesA kickup rudder and centerboard allow drama-free beaching, while the lack of boom allows for docile jibes.

Jones began sketching an evolution of the Windmill, a boat that would be less demanding and more practical for daysailing. After studying Chapelle’s drawings of working sharpies, Jones decided his boat would have a straight stem rather than the Windmill’s curved bow. He added more sheer, too, and the topsides took on something of a 19th-century workboat look. Jones’s boat is almost 2′ longer and a half-foot wider than a Windmill. He replaced the Windmill’s tall mast and standing rigging with a lower, free-standing sprit rig, and crafted a pair of elegant, leather-lined supports to cradle the hollow varnished spars when trailering.

Jones built MALU—named for a favorite family Airedale—using okoume plywood, 3⁄8″ for the bottom, and scarfed-together ¼” panels for the sides and the longitudinal air tanks. The latter are an important safety-related feature carried over from the Windmill. Epoxy and stainless-steel staples were used to join the plywood to the Spanish cedar keel, stringers, chines, and gun-wale. “It’s a faster process than using screws,” Jones said, “which are really unneeded, permanent clamps in an epoxy boat.”

Clark Mills once joked that when he was in water over 3′ deep, he was “off-soundings.” Jones’s boat has a centerboard, more complex to build than a Windmill’s daggerboard, but much more practical for a daysailer. The completed hull was coated with epoxy, and the inside of the centerboard trunk received a layer of fiberglass cloth for added protection. “I didn’t use ’glass cloth on the hull,” Jones said, “but it might be worth the extra time and weight if the sailing area and conditions warranted. With sandy shores, I kept it simple.”

MALU’s flawless AwlGrip paint job took longer to apply than building the boat. Three primer coats were used and all imperfections were carefully filled and sanded. A friend, skilled with a spray gun, helped Jones with the paint job. It’s easy to mistake MALU for a glossy, fiberglass boat. Jones estimates that building MALU would consume 250 to 300 hours of labor depending on the level of finish desired.

Michael Jones

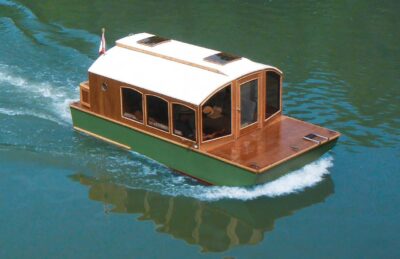

Michael JonesThe new design has ample and well-considered stowage, including these under-thwart lockers.

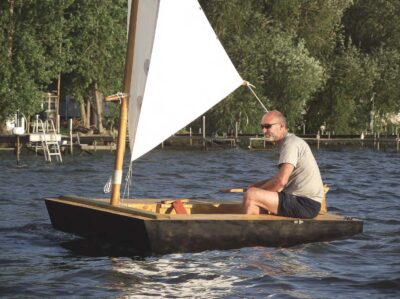

We went sailing aboard MALU on a beautiful March day in Florida’s Pine Island Sound. Dotted inshore with mangrove-fringed islands, the Sound is fascinating for both its wildlife and its wide expanses of grassy flats, about a foot deep at low tide. MALU meets one of the most important rules regarding boat selection: Choose a design appropriate for local waters.

This V-bottomed boat is reasonably stable when stepping aboard, and Jones was comfortable in putting one foot on the side deck as he rigged the sprit. As we tacked our way over the clearly visible bottom, the absence of a conventional boom made for pleasant maneuvering, with no worries about a whack up beside the head. Jones retained the hiking straps of the Wind-mill, a useful feature given that the spritsail doesn’t lend itself to reefing underway. “I hike out when sailing closehauled and single handed in wind above 10 mph,” he said. “That keeps the boat flat for optimal speed.” Like the Windmill’s side decks, MALU’s are smooth and there’s no thigh-pinching coaming to make hiking uncomfortable. This is primarily a two-person boat, but Jones has had three adults aboard and says that MALU didn’t feel overburdened. Good judgment would be the best policy here.

In light air, MALU moved out smartly enough under her mainsail. Only a light touch was needed on the tiller. Setting the jib gave an immediate boost in speed at the expense of visibility. Windmill sails have windows in them, an advantage on most small boats. MALU has a wide thwart abaft the centerboard trunk. Like the helm seat, this one has useful storage underneath it, and very nice, snap-on cushions. There’s room behind the helm thwart for a cooler.

Jones has kept his boat simple, and the more one sails, the more one appreciates simplicity. Aside from the AwlGrip paint, there’s little here that couldn’t be fixed or maintained at home with some epoxy, a couple of tools, a knife, and the contents of a ditty bag. This boat would be an interesting proposition for those seeking a fast daysailer with a traditional look and rig. It’s adapted from a speedy one-design, but has about it a flavor of the past, and a taste for always fascinating skinny waters.

Plans for MALU are available from Jones Boatworks, www.jonesboatworks.com.

MALU Particulars

LOA 17′ 4″

Beam 5′ 2″

Draft 6′ 2″

Sail area 150 sq ft

With its sheet-plywood construction and sprit rig, this design is a study in simplicity.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.