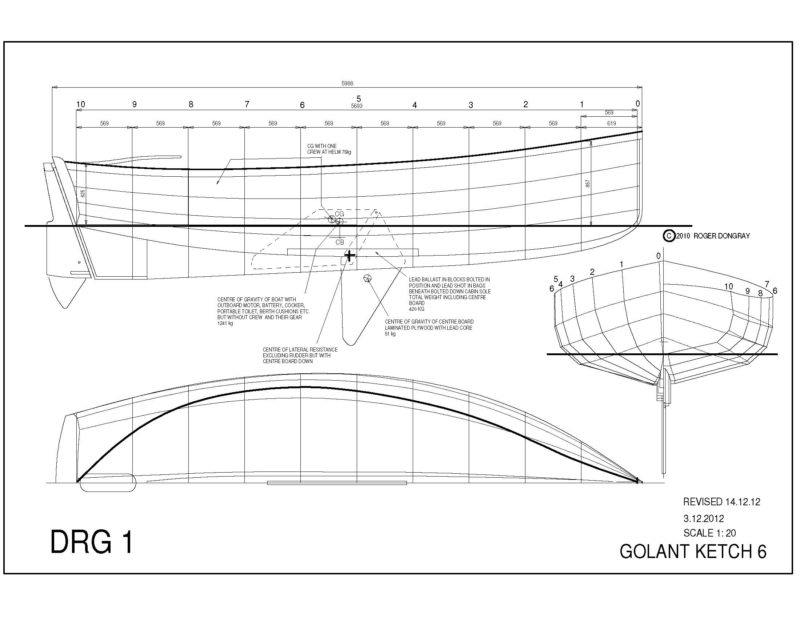

The Golant Ketch is a 20′ hard-chined camp-cruiser designed by Roger Dongray. Dongray is perhaps best known for his Cornish Shrimper, which he designed in 1976 with the intention of building only one in plywood, for himself. But after various friends showed an interest, 10 more plywood boats were built, and in 1979 Cornish Crabbers started building them in fiberglass and have now delivered 1,132 of them. At first glance the Ketch and the Shrimper seem to have similar hull shapes, but this is perhaps only because the eye is distracted by their wide-plank clinker-effect construction. The Ketch is actually slightly longer and wider, and also has a finer bow, a fuller stern, and a less-raked transom.

In September 2013, after a 24-year career in the wine business, Keith McIlwain enrolled in the Lyme Regis Boat Building Academy’s nine-month Boat Building, Maintenance, and Support course, in which about half the students get the opportunity to build a boat for themselves. For some years Keith had admired the 18′9″ round-bilged Golant Gaffer—another Dongray design, from 1993—but was worried that her fixed keel and 2′9″ draft would make her difficult to road-trailer. So when he came across the Gaffer’s centerboard cousin, the Golant Ketch, of which just one had been built at that time, he knew that this was the boat for him.

all photographs by Nigel Sharp

all photographs by Nigel SharpThe foredeck is recessed to keep lines and gear from going overboard.

It was by no means certain that he would be allowed to build one, however, because the Academy staff needs to ensure that the boats produced by each class will give the students a wide range of experience in terms of construction methods and materials, and that it will be possible to complete them all during the time available. In fact it is unusual for any boats longer than about 16’ to be built. What won the day for Keith was the Golant Ketch’s plywood construction—as opposed to the more time-consuming cold-molded or strip-plank options for the Golant Gaffer—and the fact that Dongray had produced particularly detailed drawings.

The construction began with five permanent transverse bulkheads and partial bulkheads, all of ½″ plywood, set up, upside down, on a temporary framework on the workshop floor. Longitudinal bulkheads defining the cockpit were then added, and glue-fastened with epoxy. The keel was then fitted, it being of 5”-thick Douglas-fir with the centerboard slot cut through it; it was fastened in place with silicon-bronze screws and epoxy.

Chines of 1¼″ x 1″ Douglas-fir—three per side—were notched into the bulkheads and beveled to provide suitable landings for the 3/8″ plywood hull planks. Once the hull was planked, its exterior was sheathed with two layers of 6-oz plain-weave cloth and epoxy resin before a capping, laminated from ten layers of 1/8″ khaya, was fitted to the stem and around the forefoot. The outside of the hull was then faired and painted with Coppercoat, the copper-filled epoxy resin said to negate the need for antifouling for at least 10 years, being applied below the waterline. The topsides were painted with a two-part polyurethane, and the transom and stem cap finished bright.

A cradle was then built over the hull with the corners cut away on one side to allow it to be easily turned over. As soon as that was done, all of the plywood intersections on the inside of the hull were epoxy-filleted and two coats of epoxy resin were applied to the entire inside of the boat.

For accessibility, most of the interior fitout was carried out before the deck went on. The foredeck well, coach roof, and cockpit were all constructed of 3/8″ plywood supported by a Douglas-fir structure. To avoid the need for a mast support post in the middle of the cabin, the mast and chainplate loads are taken by a substantial deckbeam made up of six 5/8″ x 3″ Douglas-fir laminations sandwiched between two layers of ½″ plywood. Most of deck was painted with Hempel Multicoat (a combined primer and topcoat) while various pieces of khaya, such as the gunwales, cappings for the cockpit coaming, the companionway hatch and trim, and the surround for the foredeck well, were coated with Rustin’s Danish Oil for easy maintenance.

This pulley and axle provide a mechanical advantage for raising the lead-weighted centerboard.

For ballast, 880 lbs of sheet lead was secured in the bilges adjacent to the centerboard, effectively by laminating it together with PU adhesive. The centerboard was made up of four layers of plywood totaling 1½″, with a large section of the two inner layers removed and replaced by 112 lbs of lead. The rudder is predominantly plywood but has a lifting stainless steel plate which limits its draft to no more than that of the fixed keel. It has two pintles on the transom and a third one on a stainless-steel tubular structure that is connected to the aft corner of the keel to provide some protection to the outboard motor.

Dongray’s drawings included the specification and position of every deck fitting, and also details of some parts that needed to be specially made, including the centerboard control system, tabernacle, and other mast fittings. Throughout the build Keith rarely strayed from any of the drawings and even then only in minor ways after consulting Dongray himself.

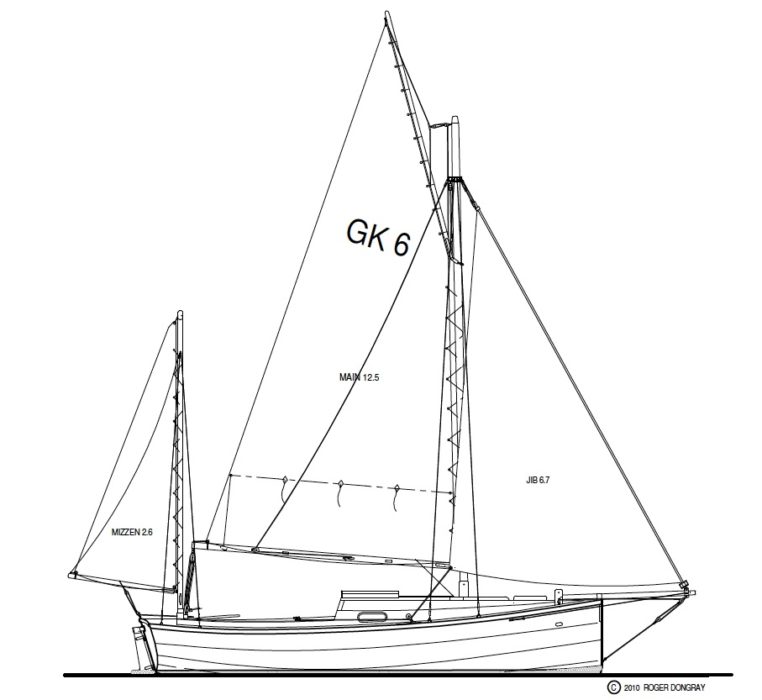

Keith built the spars of spruce. Jeckells Sailmakers made the sails; when they were complete, Keith managed to step the rig inside the workshop by maneuvering the boat under the highest point of the roof.

The course’s finale is Launch Day, when all the new boats are launched into Lyme Regis Harbour one after another, to great fanfare. This deadline accurately reflects the real world of commercial boatbuilding and the students cheerfully put in the hours to make sure their boats are ready. Keith’s latest night was quarter to one in the morning, but on a couple of other occasions he got up at 3 a.m. just to apply a coat of paint on part of the deck so it would be dry when he started work properly after breakfast.

The Golant ketch caries 235 square feet of sail.

The new boat was christened DAYDREAM as she slipped into the water for the first time on a glorious sunny day in June. Unfortunately, Launch Day also brought with it a great deal of wind, and so Keith had to make do with a short outing under reefed headsail alone. The next time he got to sail DAYDREAM was with me, one week later. The day was again sunny, but the breeze a gentle 4–6 knots. Despite the slightly disproportionate chop, DAYDREAM made her way effortlessly through the water. She had a reassuring small amount of weather helm and she tacked through about 90 degrees, albeit slowly. This was hardly surprising given her long keel and the sea state, but the plus side of that is that she tracked straight. All the sail controls are led back to the cockpit, and it will be possible to reef by reaching the main gooseneck when standing in the companionway. The mainsail didn’t come down very easily, but Keith thinks that is just a question of coordinating the easing of the throat and peak halyards more effectively. That will be important as Keith anticipates he will sail the boat with just the mizzen and jib in strong winds.

Stainless-steel tubing supports the rudder and protects the outboard.

DAYDREAM’s 6-hp Mariner outboard is mounted in a well—into which the cockpit drains—immediately forward of the rudder, and its controls can be reached comfortably. Although it is possible to steer by turning the outboard through almost 90 degrees, thanks to its prop-wash over the rudder it is unlikely that this will be necessary when going ahead.

The practical interior includes a V-berth forward with an infill to form a double, and a quarter berth to starboard; a small seat to port adjacent to a compact galley area containing a two-burner gas cooker; a chemical toilet below a hinged lid by the companionway; and a shelf outboard on each side. Most of the interior is painted, but varnished khaya shelf fiddles, centerboard trunk, and companionway trim provide a pleasing contrast.

Keith is planning to set up his own boat building and repair company, called Daydream Boats, near his home in Bristol. From there he plans to sail DAYDREAM in the Bristol Channel, where there is a massive tidal range of 43′. But he is also looking forward to putting her on her trailer and taking her to less-demanding estuaries in other parts of the West Country, to Ireland, and to the Continent.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Golant Ketch Particulars

[table]

Length on deck/19′ 7″

Beam/7′ 5″

Displacement/2,750 pounds

Draft (board up)/1′ 8″

Draft (board down)/ 4′

[/table]

For information on the Golant Ketch contact Seashell Boats in England.

I am really liking the first two issues of SBM. If you are considering requests, I would love to see a lot more pictures, and I would prefer that they were huge without having to click on them.

I’m glad you’re enjoying the publication. As SBM grows we’ll aim at adding more photographs. Presenting the photos in very large sizes poses a couple of problems. It would slow the loading of the pages and make it difficult to arrange the layout for easy reading of the text. Still, it’s a good suggestion and I’ll bump photos up to larger sizes when I can.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

Very nice job.

A possible cause of the difficulty lowering Daydream’s mainsail may lie in the position of the span which hoists the aft end of the gaff. I have had a similar problem with the main on my Clint Chase / Francois Vivier Jewell.

The forward end of the span is ahead of the mid-point of the gaff. Very little weight of the main sail is supported by the throat halyard. The gaff needs to be kept peaked up at a steep angle while the main is lowered. Alternately, the forward end of the span might be moved aft.

Look in Leather’s “Gaff Rig”. I use the paper version – 2ed. Figure 25 shows six different arrangements for rigging the peak halyard. Five of them show no attachment to the gaff ahead of the mid-point.

I haven’t changed my gaff span (yet). I get by keeping the gaff peaked up as I ease the throat halyard.

Terrific article. I would have liked to see a photo of the Cornish Shrimper just for comparison sake. Also, it would be great to see some short video of the boat under sail. Thank you, the first two editions of SBM have been great so far.

There are lots of photos and a wealth of information for the Cornish shrimper on the web sites of The Shrimper Owners Association and Cornish Crabbers, a manufacturer. We don’t, unfortunately, have any videos of the Golant Ketch under sail.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor

I quite agree. We’ll make a point of having future contributors shoot video clips to illustrate their articles.

Christopher Cunningham, editor