Clint Chase designed the Compass Skiff for the Compass Project, a Biddeford, Maine, nonprofit that works with kids. “We needed a really small, easy-to-build boat for a weekend boatbuilding festival we do every summer,” he said. “I came up with this little outboard skiff that would be easy and quick to build, stable and safe for kids on the water. It will get on plane with a 6-hp outboard; it’s a lot of fun.”

Powered by a 3.5- to 6-hp outboard, the Compass Skiffs is well suited to rivers, lakes, and other protected waters. It could also serve as a tender or lightweight excursion boat. For such a small boat, it has a high bow and a lot of freeboard and can handle the chop in an exposed anchorage. With a draft of just 3″ (with the motor up), you could do some serious gunkholing with this little vessel. A slot in the aft bulkhead provides a place to keep a paddle handy for maneuvering in close quarters, and a pair of 7.5′ oars can serve for quiet exploration or as a backup in case the motor dies. There is no skeg to help the skiff track well for rowing, but Chase notes “the boat is very light so using oars will be no problem.”

photographs by the author except as noted

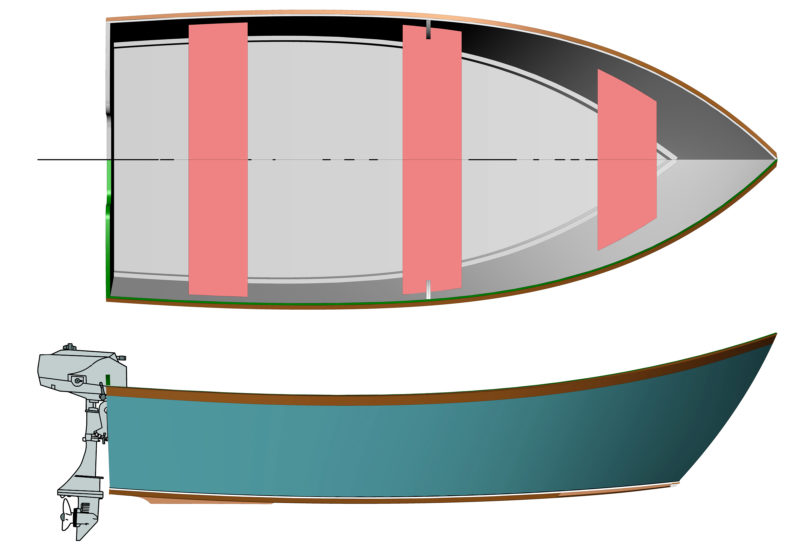

photographs by the author except as notedThe simple interior arrangements keep the skiff light and quick to build. Floorboards would be an easy addition to make to keep gear dry.

At 9′6″ long and with a beam 4′1″, it would seem the diminutive skiff would have trouble carrying the 6′4″ designer, yet the Compass Skiff has plenty of room for someone as tall as Clint, along with gear and even two small passengers. Weighing just 100 lbs, it can be easily transported with a light trailer or, with sound roof racks, by cartop. The Compass Skiff is available as plans and in a variety of kit options for do-it-yourself boatbuilders. A complete kit can be put together over a weekend and then be ready for paint and varnish.

At full speed the skiff made tight turns with ease.

The complete kit includes hardwood keel members, spruce chinelogs and stem, white pine thwarts, and easy-to-bend ash rubrails. The false stem is supplied in either ash or mahogany. The panels for the sides, bottom, and transom are computer-cut from 9-mm okoume marine plywood. The finger-jointed sides come together with a bit of epoxy in about 30 minutes. When they glue has cured the sides are assembled around two short ring frames, one in each end, and a ’midship frame using a tab-and-lock system of assembly that eliminates the need for a strongback. Tabs on the sides of the frames fit snugly in slots routed in the side panels, and after they are inserted, wedges slipped through holes in the tabs bring the sides up tight against the bulkheads. The sides of the forward frame are cut with a slight arc to accommodate the subtle compound curve the plywood sides take approaching the stem. The middle frame is squeezed by the side panels and doesn’t require the holes and wedges, though there are tabs and slots for accurate placement. The tabs are sawn off after the hull has been glued together.

courtesy of Chase Small Craft

courtesy of Chase Small CraftBulkhead tabs are inserted in mortices in the side panels (left), and those with tabs with slots are locked in place with wedges (center). Note the finger joints used to join plywood panels. The tabs are sawn flush after the epoxy has cured (right). The tabs at right are for the center bulkhead and don’t require the slots and wedges.

The forward ends of the side panels are screwed and glued to the beveled spruce stem, and the aft ends to a 3/4″-thick transom laminated with two layers of plywood. After the chine logs are installed and planed flat with a block plane, the bottom is screwed and glued in place. The epoxy-and-fiberglass kit includes fiberglass tape to protect the outside of the chine. After the assembly of the hull, the breasthook, stern quarter knees, short seat risers, seats, and oarlocks are installed.

With the bow heavily loaded the Compass skiff curled up an impressive wake, but kept the occupants dry.

When I saw the Compass Skiff arrive on a trailer at the town landing in Saco, Maine, just across the Saco River from Clint’s shop in Biddeford, the boat seemed dwarfed by the trailer, Clint’s small car, and even his two kids. The words that slipped out of my mouth were, “Cute boat,” but he seemed to agree. “It is cute,” he said.

On the afternoon we tested the Compass Skiff, the wind on the river was blowing steadily at 12 to 15 knots. We were on a body of water that is normally protected, but the wind was coming straight down the river valley and kicking up a 6–10″ chop. I envisioned a wet test ride.

We used a 1950s-vintage 7.5-hp Johnson outboard for our trials. Clint did a quick solo test. The borrowed engine was heavier and had more horsepower than he intended for the boat, and its weight, combined with Clint’s weight and that of the fuel tank, meant the stern sank heavily and the bow stood high in the air.

I took a turn at the helm, also solo, and had the same problem. We needed to get the helmsman’s weight farther forward. Clint ducked into a waterside thicket of trees and grabbed a fallen branch of about four feet long. He tied the stick to the throttle as an improvised tiller extension. Now, riding from the middle seat, Clint was able to keep the bow down and get on plane. Clint recommends using an outboard with no more than 6 hp and with the lighter weight of today’s motors, and with the ability to adjust their angle to the transom, it should be easier to achieve the ideal trim. A proper tiller extension will make it easier to keep a tight grip if you have to shift your weight forward.

With Clint and his kids aboard, there’s still room and enough freeboard for one more. You can see here that the tilt of the outboard contributed to making the bow riding high during the sea trials.

When Clint’s two kids got in the boat, they sat forward and he returned to the stern seat and removed the improvised tiller extension. Now, with weight balanced nicely, the boat skittered effortlessly across the chop. They did lap after lap around a broad basin in the Saco River, then Clint gave each of the kids a turn at the helm and the boat appeared to handle nicely in young hands, even on a blustery day.

Clint brought the kids back to the dock, and I got aboard. With Clint in the stern and me in the bow the payload was at least 375 lbs. I was anticipating getting hit with a bit of spray, but even as he gunned the outboard we stayed dry. The high bow and ample freeboard were doing their job. Clint navigated through the wind chop and then, in an added test of seakeeping ability, did tight circles and crossed through our own wake as well. The little skiff performed admirably, and no one got wet.

At the end of the day, after pulling the boat back aboard the trailer, I was pleased by how easy it was to manage the skiff. When the boat got cock-eyed on the trailer, we just lifted it up and centered it.

For someone who is crunched for storage space in the garage or needs a nimble tender, the Compass Skiff could be a good solution. And, as Clint proved with the Compass Project and his own children, it could also be a good boatbuilding project to do with kids and an ideal vessel to get them off to a good start learning how to handle a small powerboat.![]()

Peter Van Allen is a fanatic for small craft that keep him close to the water, whether it’s a surf ski, a sea kayak, a paddleboard, or a single-fin surfboard. He is based in Yarmouth, Maine.

Compass Skiff Particulars

[table]

Length/9′6″

Beam/4′1″

Draft/3″

Depth amidships/17.6″

Recommended power/3.5- to 6-hp outboard

[/table]

Clint Chase does business as Chase Small Craft. The Compass Skiff is available as plans and plywood ($1,117.50), and a complete kit ($1,725.77).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Thanks for the write up. This project wouldn’t have happened without Compass Project. The program director asked a few short weeks before the boatbuilders show in Portland, “Do you think you can knock out that kit so we can have one at the Show?” Of course, I said “Sure!” That prototype is what is featured here. We successfully built six Compass Skiffs in two days at out first annual Biddeford Boatbuilding Festival that benefits the boatbuilding programs with kids. We will have this event again next year, date yet to be determined. And if anybody wants a skiff built by the Compass Project, contact them at http://www.compassproject.org