photographs courtesy of Carl Kaufmann

photographs courtesy of Carl KaufmannIn profile, CHIPS bears a strong resemblance to the Herreshoff 12-1/2, one of the boats that inspired Carl’s Block Island 19 design.

Carl Kaufmann, at 92, likes to keep busy. He has a workshop at both of his homes, one on Block Island, Rhode Island, and the other in Mystic, Connecticut, and has built boats ranging from a 34-lb cedar racing shell to a 12-ton, 40′ yawl. If that weren’t enough to fill his days, he makes beautiful mandolins and guitars, 15 so far, and regards himself as a between a beginning and an intermediate luthier. He’s drawn more to building instruments than playing them: “After years of trying—well, maybe not trying very hard—all I can do,” he writes, “is stumble through ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ and ‘Don’t Think Twice.’”

These two guitars and the mandolin are examples of Carl’s skills as a luthier.

The list of boats Carl has built from scratch includes the Sparkman & Stephens yawl, three Graeme King rowing shells, a Butler and Hamlin 26’ centerboard sloop, an 11-1/2′ Alden X dinghy, an 11′ 2″ Shellback dinghy, a 14′ Atkin skiff, and an 8′ pram of his own design. He built a plywood pram and a 17′ Thistle-class sloop from kits. Ownership of the boats has been shared among his son, Eric, two grandchildren, and a great-grandchild—she’s only three, but her skiff is ready whenever she’s ready to row.

There was a place in the family fleet for a daysailer, and Carl considered building to an existing design. He looked at the Herreshoff 12-1/2, but it was too small and perhaps not as fast as he had in mind for his new boat. He also considered Herreshoff’s 21′ Fish Boat and Chuck Paine’s 21′ Pisces, but these were keel boats and Carl preferred something not quite so deep. He kept looking around at other designs, but nothing quite felt right, so he decided to draw his own design. Although he had made his career in journalism, his education was in naval architecture and marine engineering. So, he drew up his Block Island 19, a centerboarder with an overall length of 19′, a waterline length of 15′, a beam of over 7′, and a draft of just 2′ with the board up. An 1,100-lb lead keel would bring the boat weight up to 2,500 lbs, “an extremely light boat,” he notes, for its type, more substantial than a 12-1/2 but substantially lighter than the Fish Boat or Pisces. For the rig he drew a generous gaff mainsail and a small self-tending jib on a traveler. For construction, carvel and lapstrake—either traditional riveted seams or glued plywood—were options, but Carl settled on a three-layer composite hull.

With the drawings finished, Carl began construction. He built the hull on ten 1″-thick molds, a structure strong enough to allow him to raise it and the hull with a chain hoist when planking was finished and turn it right-side up. The steam-bent frames were wrapped hot around the molds, which were undersized to accommodate the frame stock. The first layer of planking was 5/8″ cedar strips, nailed and edge-glued with Aerodux resorcinol, an update to the pre-epoxy standard. Like its predecessor, it is quite tenacious and even boil-proof, but is more forgiving of small gaps in the seams between planks.

Prior to painting, the inner layer of strip planks was evident. The two additional layers of diagonal planking made up the full thickness of the hull, almost 7/8″.

About 70 strip planks went into each side of the hull for that first layer, and after it was sanded smooth and fair, Carl applied two layers of thin cedrela, a variety of mahogany also known as Spanish cedar. The planks, just shy of 1/8″ thick, were not rotary-cut as plywood veneers are, but quarter-sawn from timbers by a horizontal bandsaw mill. The stock was 12″ wide or more, so Carl cut it into strips 3″ to 5″ wide, spiled them, and applied the two layers at opposing 45-degree angles. Nylon staples, driven by an air gun and set just below the surface of the mahogany planks, held the planks while the epoxy cured and then remained in the hull. The planks weren’t required to take a reverse curve to fair into the keel, so the staples were enough to push the cedrela tight to the form.

The completed hull was leak-proof, light, and so stiff that it required few ribs to strengthen it. The exterior surface was quite smooth after the last layer of planks went on and required very little sanding prior to rolling the hull upright.

Carl had the lead keel cast—in a mold he made—by a Connecticut boatyard with a foundry. It has a slot for the centerboard and was connected to the hull’s oak keel, without any deadwood in between, by bronze bolts that run through the heavy oak floor timbers.

The hull’s three layers of planking required minimal framing.

The interior work—installing floors, framing, and bulkheads—was all pretty straightforward, but the deck framing was more difficult. Like any large open-cockpit boat like CHIPS, it requires a lot of carlins and half beams, and the shelf and sheer clamp need to be sturdy because the load on the deck is not supported by an inherently strong arched beam spanning from sheer to sheer.

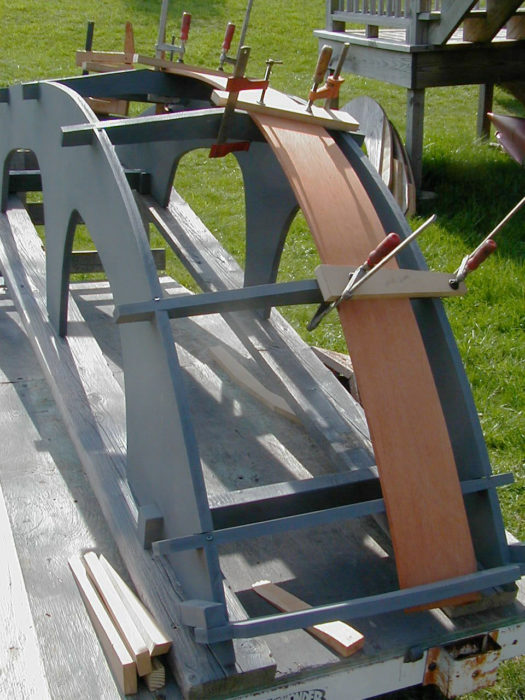

The coamings were designed to serve as comfortable backrests so they were steam-bent over a jig with crosspieces cut with 5-degree slopes.

The coamings posed an interesting challenge. Carl had some beautiful, broad South American mahogany, wood that demanded a bright finish, so it had to be handled carefully every step of the way. The 9″- to 10″-wide coamings would meet at a point forward and be angled outward at 5 degrees to serve as comfortable backrests for people sitting on the boat’s side benches. Carl decided to make each full-length half of the coaming in two 3/8″-thick layers.

He started with a doorskin pattern and a bending jig, which had cross pieces angled at 5 degrees to meet at a peak in the middle. He steamed the shaped mahogany pieces, applied them to the jig, and left them to cool. After they had dried, he installed them in the boat, and when everything fit properly, he removed the four pieces, applied epoxy to the interior surfaces of each pair, and reinstalled them to cure in place. He could then remove them to do any finish work required before permanently installing them. The coamings alone took somewhere between 50 to 75 hours of Carl’s time.

CHIPS has plywood decks, sealed with epoxy prior to installation, and covered with Dynel everywhere but the foredeck, where Carl used canvas because Dynel wide enough to cover the foredeck in one piece wasn’t available. Carl used some of his South American mahogany for the seats, to be bright-finished, of course, and tried his hand at wood-turning to make supports for them. Some of CHIPS’s bronze hardware was cast from patterns Carl made, and he got a Mystic Seaport rigger to teach him how to splice wire so he could make his own standing rigging.

Carl made the mast hollow to save weight. He used this same bird’s-mouth construction for the gaff and jib boom.

The mast is made of Douglas-fir, and the gaff and jibboom are Sitka spruce, all made hollow with bird’s-mouth construction. The boom is a box beam, made from Sitka spruce salvaged from a much larger box-beam boom that had been abandoned at a shipyard. The boom is relatively heavy compared to the other spars, but Carl likes to have a bit of weight pulling the foot of the sail down. It tensions the leech and keeps the gaff from falling off the wind.

Carl didn’t build the boat with accommodations for an outboard, so for auxiliary power, he uses a single long oar. With the oar set in one of the two oarlocks, he rows on one side, facing forward and standing. Steering with the tiller between his knees, he makes about 2 knots. The generous sail area can take advantage of very light breezes, so he has yet to row very far.

Sitting on her trailer, CHIPS shows her modest draft.

CHIPS has a few sailing seasons to her credit now, and Carl can imagine a few tweaks he’d make. He’s giving some thought to adding a side mount for an electric outboard. While under sail, the motor and bracket would stow in the bilge. CHIPS has a light weather helm and a longer centerboard case located farther aft would help, but that’s a project for a second Block Island 19. Giving CHIPS a small bowsprit would achieve the same end, but the weather helm isn’t so much of a problem that moving the sail area forward is really necessary. Carl has mused about an alternate rig, marconi instead of gaff. Downwind speed would suffer a bit, upwind speed would improve—perhaps a wash in a day’s sail, but an interesting experiment that would require no change to the boat beyond switching the spars, shrouds, and forestay.

The forward ends of the coamings support the roof of the cuddy.

Musings aside, Carl has been pleased with CHIPS. She performs well, and the high-peaked gaff makes her quite weatherly for a gaffer. Downwind, CHIPS is “extremely fast,” says Carl; “you pull up the centerboard and that big mainsail really goes.” Carl made CHIPS’s run a bit flat rather than full so she isn’t dragging a big quarter wave that would slow her down. Off the wind, she has kept pace with 420 Class Dinghies—up until they get enough wind to put them on plane. “She’s dry, easy to handle, and she snap-tacks in a jiffy. We couldn’t be more pleased with her performance in choppy weather; when she’s properly set up, she sails herself.”

Carl took pride in CHIPS’s connection to her Block Island birthplace and had her sails made by an island sailmaker.

If Carl enjoys building boats a wee bit more than sailing and rowing them, just as he prefers making guitars to playing them, there’s a good chance he’ll find a reason to build another. Come winter, when the fleet is hauled out, he’ll have to have something to keep him busy.![]()

Have you recently launched a boat? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share your story with other Small Boats Monthly readers.

What a beautiful boat and those instruments, amazing! To be building such beautiful things in one’s nineties, now that is an example to inspire all of us, particularly those of us who are getting on in years.

Thanks for the heads up that Carl is in his 90s. At 76, I’ve often wondered how long I can keep building small boats. His work is amazing. Regarding the motor mount, I installed a side bracket on my Somes Sound 12-1/2 and it was a total nuisance. Plus, removing or installing the electric trolling motor while sailing is not as easy as you might think. A long canoe paddle was all I needed. Thanks again for the inspiration.

That is one busy man and indeed an inspiration. I’m 71 and just starting on building boats. Have done knives and dulcimer and tools or furniture, some kits, some scratch. I am amazed at the industry and energy demonstrated and take it to heart. I salute you sir. Thank you.

Carl has shown the way for those of us who believe the best is yet to come. I much prefer the notion of “re-firing.” I’m totally inspired. For anyone thinking about when would be the best time to retire, it’s time to consider how you plan to re-fire!

I would love to know the upwind performance comparing centerboard up vs down.

Are plans available for the Block Island 19? I’m looking for a design in the 19-21 foot range.

I also would like to know if plans are available for the Block Island 19. Thank you

Make that three of us wondering if plans for the Block Island are available.

I prefer a little weather helm, because it lets me feel how the boat is performing. I owned for 18 years a little 21′ cruising cutter designed by Ed Monk Sr., and built in 1935. I wanted to avoid employing a crane when it came time for mast maintenance, so I installed it in a tabernacle. When it came time to reinstall the mast, I didn’t give it quite as much rake as it had originally, and ended up with neutral helm. I could no longer feel the rudder lifting the boat to windward, and had to watch constantly to to avoid luffing or stalling. The tabernacle worked fine, by the way, with a come-along and a scissors pole pivoting off the shroud chain plates. I save having to get in line at the boatyard.

Phil Bolger comments on this somewhere.

A lovely wee boat!

That word “jibboom” (jiboom, jib boom) though – the spar in question is a club. Any who’s had to share a foredeck with one can tell you why. A jib boom is an extension of a bowsprit in the same way a topmast is an extension of a lower mast.

As well as a fine craftsman, Carl is also a gifted teacher. He donated his time to teach an acoustic guitar building course to my woodworking students (and me) at the Block Island School. It was an amazing experience and these “kids,” now around 40, still talk about it. Now that’s education!