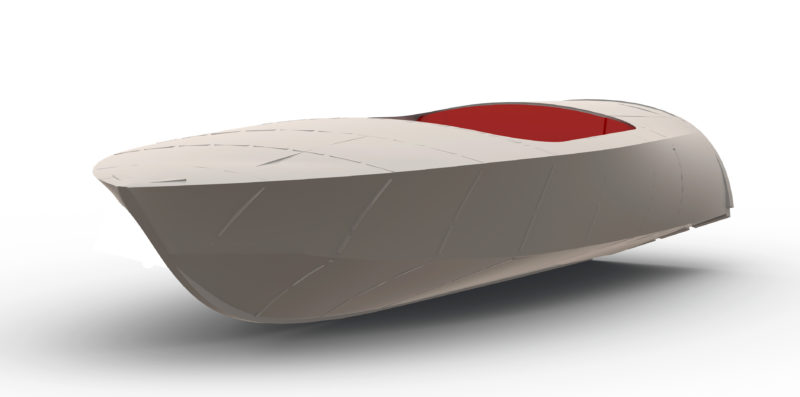

BUNDUKI is a sport boat built to Australian John Georgalas’s Deep V 16′ design. Initially, the design was to be a one-off for an American friend, but the drawings have since been made available through John’s company, Classic Wooden Boat Plans (CWBP). For this design, John was inspired by the 17′ WYNN-MILL II, designed by Jim Wynn in the early 1960s. That boat was raced with great success, including a victory in the six-hour Paris Race. Wynn subsequently collaborated with Walt Walters and Don Aronow on a production version, the Ski Sporter, which was later dubbed, and became much better known as, the Sweet 16. That was the first boat built by Aronow’s company, Donzi Marine, after it was formed in 1964.

The Sweet 16 was about a foot shorter than WYNN-MILL II, and it lacked the original boat’s pronounced tumblehome aft, presumably because of the practicalities of molding it in fiberglass. At the height of production, 20 of these boats were produced each month. President Lyndon Johnson owned one, and the Israeli armed forces had a dozen of them, some of which saw action in the 1967 Six Day War.

The original brochure for the Sweet 16 described it as the “softest riding, driest high-speed sports boat ever built.” The 24-degree deadrise would have contributed to those characteristics, and this has been retained in the Deep V design, as has WYNN-MILL II’s tumblehome, which John and his American friend particularly admired.

all photographs by the author

all photographs by the authorBrian Reford, a student at Lyme Regis Boatbuilding Academy, built BUNDUKI with an eye toward wake-boarding and water-skiing. He was particularly drawn to the design’s pronounced tumblehome at the transom.

In March 2013, Brian Reford enrolled in the nine-month Boat Building, Maintenance and Support course at the Lyme Regis Boat Building Academy, where he had an opportunity to build a boat for himself. He wanted one that could be used for water-skiing and wake-boarding and, after looking at “masses of designs” on the Internet, he found the Deep V and ordered a set of plans from CWBP.

Having printed the drawings full size, Brian decided there was no real need to carry out any lofting, although he later came to regret that decision. His starting point was to make the eight permanent frames—mostly ring frames to include the deckbeams, but with three hull frames in the open cockpit area, which needed temporary braces across them. The way he decided to construct them—from ¾″ red cedar, 8″ deep in the keel area but much narrower in the topsides and across the deck, and with halving joints between their various components—was quite different from the detail in the CWBP drawings. He made those changes with the guidance of his course tutors, and from then on he gradually came to rely less on the plans and more on his own instincts and the tutors’ advice, a course of action which, he later realized, allowed him to learn much more than he would otherwise have done.

BUNDUKI, built to John Georgalas’s Deep V 16’ design, is a descendant of WYNN-MILL II, a legendary raceboat that gave rise to the speedboat company Donzi Marine.

The various fore-and aft components came next: the 3″ x 2″ mahogany keel, with four laminations along the majority of its length and twelve around the stem; the spruce chine logs, which started off at 1 ¾″ x 1″ before they were beveled; and three 1 ¼″ x ½″ red cedar stringers each side on the bottom and one at the sheer. The bottom was then cold-molded with three layers of 3/16″ Robbins Elite plywood, all in the same diagonal orientation but with their joints staggered. Brian decided to turn the hull the right way up to fit the stringers and the two layers of 3/16″ ply to the topsides, not because it would be any easier to do so—although it would be in the tumblehome area aft it would be harder at the flared bow—but because it gave him the chance to first check the fairness of the chine in the forward sections by eye and make small adjustments to it.

BUNDUKI is built of three 3⁄16” layers of cold-molded plywood laid over stringers set into notched frames. The angles of the deadrise and transom almost exactly matched those of the jet ski that provided the engine.

Now it was time for Brian to turn his attention to the power unit. He could, of course, have fitted a similar type of engine to the one originally specified for the Sweet 16—a 110-hp Volvo Penta with an outdrive—but he had other ideas. Primarily for safety reasons when water-skiing, he wanted to fit a jet drive, and he decided the best way to acquire one would be to take one out of an old jet ski. He managed to find a suitable one—a Kawasaki STX 3-Person Cruiser with a three-cylinder, two-stroke 130-hp engine—on eBay. Having removed its important parts, he cut a hole in the underside of his boat, rabbeted the outside of the hull around the hole, fitted the jet unit’s flange (which had been part of the jet ski’s hull) into the rabbet, and bolted it in. Fortunately the angles of his boat’s deadrise and transom almost exactly matched those of the jet ski. He could have kept the engine and jet as one unit and fitted them into the boat together—and his course tutors encouraged him to do so—but he wanted “the engine to be part of the boat and not the jet ski,” so he fitted conventional engine beds for it.

The bottom was reinforced with 15-oz biaxial cloth, and the entire hull was then sheathed in 6-oz cloth before being filled, faired, and painted.

But before installing the engine itself, he had more work to do on the bottom. After fitting a ¼″ plywood sub-deck and machining a 2″-wide rabbet around its perimeter, he turned the hull upside down again to allow the outside of it to be fiberglassed with 15-oz biaxial cloth over the bottom panels and then a 6-oz plain-weave cloth over the whole of the outside, around the sheer, and into the rabbet. The hull was filled, faired, and painted, and then turned the right way up again.

The visible deck is an overlay applied to a ¼” subdeck. It consists of a khaya kingplank and covering boards, and spruce planks caulked with black polysulfide.

A 3mm-thick decorative deck was then fitted. This consisted of a khaya kingplank and margins, and fore-and-aft-laid spruce planks caulked with Sikaflex and then varnished: three coats of two-pack followed by seven coats of single-pack. The dashboard and engine box top are both veneered with ash, with khaya trims and inlays. After every piece of plywood was epoxy-coated, the visible areas of the cockpit—the seat fronts, the inside of the hull, and the cockpit—were all lined with a polypropylene carpet.

The “gear shift” lever of the controls operates a bucket that diverts the jet drive’s water either forward or astern. The controls take some getting used to, for the shift’s neutral position directs the water straight down, causing the boat to move slightly.

On the Lyme Regis Launch Day, which is the culmination of the course, Brian christened his boat BUNDUKI, which is Swahili for “rifle,” in memory of his father, who once ran a gunsmith shop in Nairobi and who had recently died. BUNDUKI managed to get up to 38 knots that day, but when I met up with Brian six months later on a small lake adjacent to the River Thames at Pangbourne, environmental considerations would have restricted us to about 5 knots even if local by-laws didn’t.

Power is supplied by a two-stroke, 130-hp engine harvested from a Kawasaki Jet Ski.

The principle of a jet drive is that the engine, which is always in gear, drives a large impeller, which draws water through an intake in the bottom of the boat and discharges it at high velocity through a nozzle at the stern. The “gear lever” controls a bucket which diverts the water to drive the boat forward or astern, but when the lever is in neutral the flow is downward; this often results in a very slow, somewhat disconcerting, movement of the boat. With no rudder, the wheel turns the discharge nozzle to port or starboard.

BUNDUKI’s steering system allows about one-and-a-half turns hard-over to hard-over. This differs from jet skis, which have bike-type handlebars. At very slow forward speeds, BUNDUKI is difficult to steer in a straight line. However, steering became noticeably easier at about 5 knots, and Brian told me that at higher speeds it isn’t an issue at all. She is very easy to turn: At slow speeds with the wheel held hard over she will just keep going round in a circle in her own length, and Brian said that she “banks massively” when turning at top speed. When going astern, however, she takes a long time to respond to any turn of the wheel. The engine sounds a bit rough when it’s ticking over, but at slightly higher rpm it is much smoother, albeit with a deep throaty roar. With the whole timber hull acting like an acoustic musical instrument, it sounds very different from a jet ski. Brian thinks that the 55-liter fuel tank located under the foredeck will provide “just a few hours’ playing and that’s it; it isn’t very economical, but it’s a toy, so you’ve got to look past that.” He advances a similar argument to justify his tolerance to the high-speed noise levels.

When I rode with him, Brian had yet to use BUNDUKI for water-skiing or wake-boarding. In fact he still hadn’t fitted a ski pole, but he wants to take some care with this to make sure it is removable so as not to spoil the look of the boat. He will then be ready to take her to one of the several lakes near his home on the Thames. “But really the ideal place would be one of those lakes in America,” he told me. “A bit far away, but maybe one day.”![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

You can see BUNDUKI at speed in a video posted on the Boat Building Academy’s Facebook page.

BUNDUKI Particulars

[table]

LOA/16′ 4″

LWL/14′

Max Beam/6′ 9″

Draft (est.)/1′

The Deep V 16’ is similar to the legendary Donzi Sweet 16 model, which in turn was a development of WYNN-MILL II. The Sweet 16, however, did away with the alluring tumblehome—presumably to ease production. Designer John Georgalas has revived the shapely hull in the Deep V 16’.

Plans for the Deep V 16 are available from Classic Wooden Boat Plans. The cost for the set is US $195. Plans are supplied as PDF files, which buyers must have printed.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

This article is great! Keep them coming. This is the type of article that will attract more and younger people to building wooden boats. This type of wooden boat plays into a completely different market than you have been trying to attract. I am pretty sure this market is much bigger than you think.

A job very well done! Congratulations, and thanks for the article. I very much fancy a Wyn-Mill II, but without as much tumblehome. It would be great with a Volvo 4-cylinder diesel, say a D3-170, and drive leg!

There is a reference to regret about not lofting, but do the plans come with a full table of offsets? If the plans do not come with a full set of offsets, any clarification on whether the reference is to some intermediate step like using battens to make sure lines taken off the full size plans are fair as transferred to frames?

I forwarded the questions to John Georgalas at Classic Wooden Boat Plans. Here’s his reply:

“All of the frames are included in the plans as full-size patterns. They’re saved as PDF files, so all the builder needs is a Kinko’s nearby for printing. All frames have notches premarked so fairing is easy. The height above baseline is also provided. Lofting really isn’t necessary unless the builder wants to change the overall shape or size.

We’re happy to offer advice and help. Just send us an email. We provide free changes to all plans sold, mostly buyer-requested custom dash boards or engine beds. One builder, Stu Stocker, wanted a transom to suit an Alpha One leg and engine beds to fit a standard V-6 Mercruiser. We adapted the plans for him and the combination he chose to power his boat worked very well. It puts it up on a plane very quickly.”

Christopher Cunningham, Editor