BEATRICE is a modified Saint-Pierre dory—a type once common on the waters of Canada’s Maritime Provinces. Born on the islands of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon off the coast of Newfoundland (French possessions to this day), the Saint-Pierre dory was a local response to a French government requirement for cheap, durable, and safe fishing craft for local fishermen.

Taking the traditional rowing dories of the region as a starting point, the Saint-Pierre dory gained size and weight and evolved higher ends and greater freeboard. It also gained an engine—usually a single-cylinder “make-and-break” two-stroke coupled to an ingenious retractable propeller and shaft. The boats sometimes had forward cabins. BEATRICE is a further evolution of this concept, and was designed by David Roberts of Nexus Marine for construction in fiberglass-sheathed plywood.

Photo by Karol Wilczynska

Photo by Karol WilczynskaDavid Roberts of Nexus Marine (Everett, Washington) modified the traditional Saint-Pierre dory for recreational use; New Zealander Alan Litchfield built his boat, BEATRICE, to the design, with modifications to suit local conditions.

“It’s brilliant,” says Alan Litchfield, who had BEATRICE built for use in his native New Zealand waters. Roberts, he says, has “taken all the core elements of a traditional Saint-Pierre dory and made a few minor modifications—more beam, lower freeboard, a wider transom—to create a great little boat that’s stable, predictable, and loads of fun. I wanted a boat I could trailer to places like the Kaipara or Hokianga [Harbours] where Karol [Wilczynska; his wife] and I could spend our weekends exploring.” Trailering, he says, “also saves us having to moor her or keep her on a marina berth.” She lives in the couple’s suburban driveway when she’s not being used.

With beam of 8′ 9″, the David Roberts–designed Saint-Pierre dory is 3″ over the legal trailerable limit in the United States. Therefore, a permit or a modest tolerance for risk will be required to get her home from the ramp in the United States. BEATRICE carries thick solid-mahogany rubbing strakes, which swell her beam to 9’6″ (2.9 m); in New Zealand, that’s not a problem, and Litchfield can tow BEATRICE behind his TD5 Land Rover Discovery with only a few restrictions. The boat has proven easy to launch and retrieve, although her flat bottom and lack of self-centering rollers mean that retrieving is a two-person job.

Photo by Karol Wilczynska

Photo by Karol WilczynskaBEATRICE’s modifications from the original plans include a slightly raised house, triple skegs (rather than one) for handy beaching, and accommodations that include a private forward cabin.

Aside from the thick rubbing strakes, Litchfield and the boat’s builder, Randall Haines, decided on several changes to the plans, largely to accommodate New Zealand conditions and their own boating experience. While designer Roberts wasn’t totally thrilled with all the changes, he was always consulted and, according to Litchfield, his advice was heeded wherever possible.

Another change to the original drawings includes the addition of an enclosed, slightly raised wheelhouse, rather than the specified hardtop with side curtains. The ability to close off the helm from the cockpit turns the boat into an all-seasons cruiser—a plus because boating is possible year-round in New Zealand. Winter weather, however, is colder and wetter, while in summer the ability to get out of the sun is welcome. Canvas covers enclose the whole cockpit for cozy overnighting.

Litchfield and Haines raised the wheelhouse roof a fraction so he and Karol could enjoy standing headroom. The roof framing itself has been modified from longitudinal to transverse laminated frames. It has more curvature, for better water shedding, and is stronger: the roof easily supports a standing adult.

Roberts’s main concerns with changes to his original design revolved around increased weight up high, exacerbated, he felt, by Litchfield’s decision to move the galley from its forward position below in front of the helm bulkhead to the wheelhouse opposite the helm. BEATRICE’s galley is certainly very serviceable, although seating accommodation has been lost (Litchfield has compensated somewhat with a folding jockey seat), and the space once occupied by the galley has become a useful navigation station. Aft-facing seats were also added to the cockpit: an icebox lives under one and the LPG bottle under the other, nicely isolated from the cabin.

“Roberts designed the boat primarily as a day cruiser; we like to use her for extended trips, sometimes of a week or more,” explained Litchfield. “So the ability to close off the accommodation was important to us and we wanted more usable galley space, since we cook real meals aboard. I’m also nervous about gas bottles housed down below. In the plans [the gas] was all the way forward. I feel happier with it up on deck.”

Down below, Litchfield ditched the hanging locker, changed the head layout, and moved a bulkhead forward and took it only partway to the coach roof. He also dispensed with a plumbed head and opted for a portable chemical toilet instead. The main advantage of the new layout is that the forward cabin can be closed off for privacy. On overnight expeditions, the portaloo can be moved out to the cockpit.

Photo by Karol Wilczynska

Photo by Karol WilczynskaModern construction meets traditional appearance. BEATRICE’s framework, seen here, will be “planked” in marine plywood, which will in turn be sheathed in fiberglass set in epoxy.

The other major modification was necessitated by the decision to fit a larger engine than was specified. BEATRICE runs a 60-hp four-stroke Yamaha outboard in a box-well; a 50-hp unit was specified, but the model was no longer available. The 60-hp has a wider cowling than the 50-hp, requiring a wider motorwell. A wider well means less buoyancy aft. Other modifications included enclosing the spaces between the coamings/sidedecks and cockpit sole, and along either side of the engine, to make lockers. Breather holes were added to allow airflow below decks.

Changes to the outboard well design probably caused everyone the most concern. Indeed, early trials indicated BEATRICE was stern heavy, with water slopping over the well and through the scuppers into the self-draining cockpit. Performance was good with the bigger engine—8.5 knots at half throttle—but Litchfield was uneasy about water splashing onto his batteries, originally installed in front of the engine well. The solution was simple: the batteries were moved forward and down low in the boat under the chart table, close to the instruments and electronics, making a subsequent rewiring job much easier. Aware from the beginning of Roberts’s concerns about top weight, Litchfield installed the 100-liter fuel tank between the frames under the floor amidships. In the original design a much smaller tank is positioned under the helm seat. Acting in tandem with a 100-liter water bladder, also below the waterline, as ballast, he was confident the tanks would address any trim issues. There’s no more water slopping into the cockpit, and he reports BEATRICE’s motion to be very stable—stiff, in fact.

There are other, less visible, variations to Roberts’s plans: three solid timber skegs rather than one, so BEATRICE can take the ground with minimal damage, and substantial changes to the bow. Litchfield has added a bowsprit and fairlead, along with a Lofrans electric capstan. The bow area has been greatly strengthened with solid timber blocks, to cope with long periods at anchor and to accommodate the substantial ground tackle that’s mandatory when cruising in New Zealand.

Photo by Karol Wilczynska

Photo by Karol Wilczynska

With the hull inverted, BEATRICE’s motorwell and accommodations are built. The well seen here is larger than the one specified on the plans.

The Yamaha 60-hp gives BEATRICE a top speed of around 17 knots. A cruise speed of 8.5 knots is comfortable, and 7.5 knots at 2,700 rpm seems to be the best compromise between speed and economy. The box well takes up quite a bit of space, but the engine is easily accessible and can be tilted until the propeller is clear of the water. BEATRICE will run for 20 hours on 26.4 gallons (100 liters) of gas.

Atrip to Tiritiri Matangi Island in Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf showed up BEATRICE’s charm and also some of the idiosyncrasies of a dory design. With a flat bottom she behaves more like a dinghy than a launch, relying on her skegs to keep her on the straight and narrow. Underway she tracks well enough, but at low speeds she can be a bit tricky in a crosswind. I was surprised at how well she coped with short, steep seas in Tiri Channel, easily dealing with waves on the nose or slightly from the beam, provided the skipper adjusted her speed to suit the conditions. Litchfield has braved 40 knots and 10′ seas without incident.

Where BEATRICE really came into her own was in the calm waters of a quiet bay at Tiritiri Matangi Island. We nosed carefully inshore, one of us on the bow directing the helmsman through a maze of rocks and reef, to a beautiful sandy cove where we beached her on the sand. With the engine tilted up she draws little water, allowing safe inshore exploration. A flat bottom means she can take the ground—and she remains upright when she does so. These are traits the owners have found invaluable during their ongoing exploration of many of the country’s large, tidal harbors.

We enjoyed coffee and cake while watching the wildlife—marine and terrestrial—before rain and deteriorating sea conditions drove us back to civilization. Alan Litchfield and Karol Wilczynska would be stepping back aboard later in the day, happy to spend the weekend poking around Mahurangi Harbour and maybe Kawau Island to the north, regardless of the weather. BEATRICE is a busy girl.

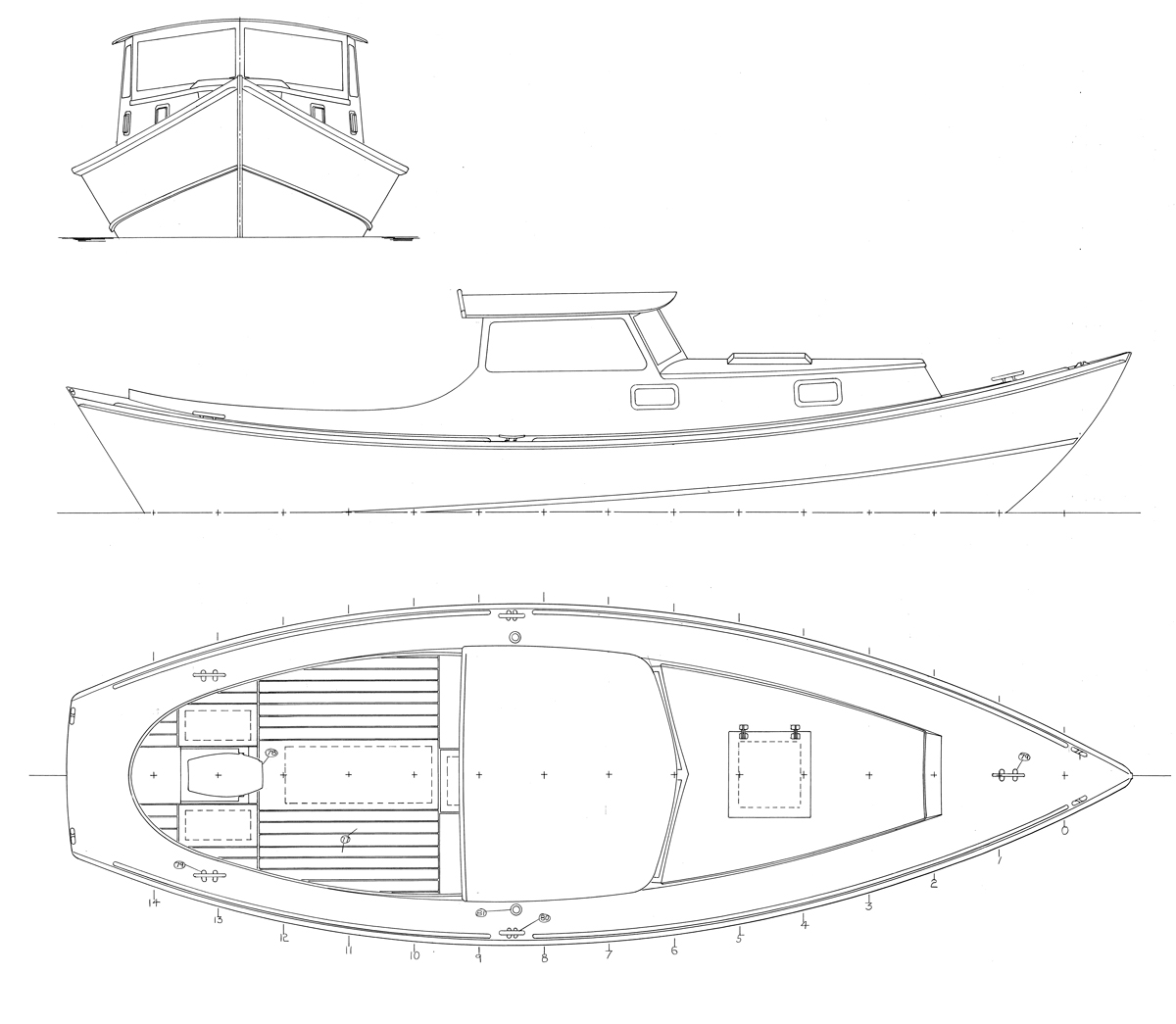

The Nexus Saint-Pierre Dory, as drawn.

Plans for the 27′ St. Pierre Dory are available from Nexus Marine for $125.

Lovely boat. I have two, one 20′ and one 35′ 6″. Designed and build by Howard Pascoe of Whitianga, New Zealand. The first one KAIWAKA in 1956 and JOHN DORY in 1970.

A friend and I built this modified St. Pierre dory in ’75 and fished her commercially for 5 years. We male-molded it, solid fiberglass hull with glassed plywood topsides and a wash deck. 30-hp Isuzu diesel and steered with a rudder-to-wheel cable system. Could also be rigged for sailing. Thanks to John Gardner for the modified plans. Here she is taking a break at Santa Cruz island.

CAPE JACK was launched the Monday before Xmas ’22, after 16 years building. I am delighted with her. Just sorting ballast out and few other minor details and she will be ready to explore our gulf.