Rollin Thurlow has been building and restoring wood-and-canvas canoes for 38 years. This spring, Rollin took a short break from his shop, the Northwoods Canoe Company in Atkinson, Maine, to paddle the Allagash Wilderness Waterway in celebration of its 50th anniversary. As always, he ventured out in his beloved Atkinson Traveler, the same canoe he’s been paddling for 25 years. “I wouldn’t paddle anything else,” he says. He designed the boat in 1982, as one of a series of plans to be included in The Wood & Canvas Canoe, a revered building guide that he wrote with Jerry Stelmok of Island Falls Canoe, also located in Atkinson.

Back when he designed the Atkinson Traveler, Rollin began with what he most respected, the working boats that E.M. White built in central Maine beginning in the late 1880s; White’s designs were the mainstay of the guides, foresters, and wardens of the era. Rollin believes that White’s 18′6″ and 20′ Guide models, built to handle Maine’s often shallow and rock-strewn rivers, neared perfection for a regional craft.

all photographs by the author

all photographs by the authorThis special commemorative Atkinson Traveler was built to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. The cedar ribs and planking come from the AWW, the rails were made from Baxter State Park spruce and the figured maple is from northern Maine’s Piscataquis County.

As Rollin turned to his own design, he realized that a shorter vessel that maintained the versatility of the Whites would provide a novel addition to the field of wood-and-canvas wilderness tripping hulls. He opted for an overall length of 17′ 6″; at 75 lbs it weighs in about 5 lbs under the White 18′6″. The most notable change that Rollin made was to alter the White’s fine entry, which made the designs very fast, but that sharpness at the bow led them to dig their nose into larger waves; Rollin gave the Traveler a more balanced entry, making the bow a bit fuller, giving his design more buoyancy in uneven water. He added about ½″ of rocker to the Traveler, bringing it up to 1-1/2″. The 35-5/8″ beam is very similar to the 18′ 6″ White and increases the Traveler’s stability and carrying capacity. The Traveler’s 5 degrees of tumblehome, gently curved sheer, and overall profile remain nearly identical to the White, which gives both boats a minimalist’s elegance at first glance and links them to the White’s ancestor—the Penobscot bark canoe.

While Rollin’s design is foremost a river boat, the Traveler’s shallow arch bottom, another trait inherited from the White, does slightly reduce initial stability (compared to a flat-bottom) for river use, but not enough to compromise the boat’s proficiency at poling, which requires standing and is an all-important skill for canoe tripping in Maine. The shallow arch also reduces wetted surface—and the drag associated with it—making the canoe faster. The Traveler draws about 6″ when loaded with a week’s worth of gear. The design is well rounded enough that it converts many first-time users with its virtues, and it’s not uncommon for paddlers to proclaim it “the ideal canoe.”

Garrett Conover, a veteran North Woods guide, has paddled tens of thousands of miles, and much of it at the helm of an Atkinson Traveler. According to Garrett, the trick in designing a wilderness hull is to find just the right balance of opposing design parameters. A high functioning design must excel at all aspects of wilderness travel, including flatwater, whitewater, downstream and upstream. Garrett explains that the game changer for a tripping hull is its ability to mesh high load capacity with superb handling, and notes that such a balance is very difficult to achieve; Rollin does so by the placement of compound curves in and around the quarters whereby the hull masterfully combines the speed attributes of a sharp entry with a sudden flare to accommodate load capacity as well as add buoyancy that keeps rough water on windswept lakes and whitewater on fast moving rivers from filling the boat.

Upstream travel was an essential skill when traveling in Northern Maine until the mid-20th Century when roads became more prevalent. The region’s shallow and rocky rivers were best ascended in a long canoe with shallow draft. Nothing poled as well as the Whites and the Atkinson Traveler carries on this tradition.

“The Traveler is nimble in whitewater,” he says. “It poles well, it paddles well, and it’s small enough so it’s not quite as heavy as some. It portages well in any country.” Garrett’s personal preference is the Deep Traveler, which carries 15″ of depth amidships compared to the conventional Traveler’s 13″. The Deep Traveler is the design of choice for those, like Conover, who routinely head out on self-supported trips for weeks on end. “To me,” says Garrett, “it’s the pinnacle of wilderness canoes thus far.”

Elisa Schine worked as an instructor at a wilderness canoe camp before landing at Northwoods Canoe Company. She recently took her boyfriend on his first canoe trip and chose to borrow one of Rollin’s Atkinson Travelers, instead of using the round-bottomed Prospector she owns, because of the Traveler’s stability and ease of handling: “I didn’t want to tip him into the river the first time he got aboard a canoe.”

On a bright spring day, I traveled to Atkinson to paddle in the town’s namesake Traveler. Rollin, who celebrated the thousandth canoe to pass through his shop in 2014, had recently finished a special commemorative Atkinson Traveler. The stripes of its tiger-maple thwarts morphed from light to dark and undulated as I move around the boat. The bird’s-eye maple decks’ swirling made them look like old contour maps. The rails were made from Baxter State Park spruce. The gunwales of the standard-issue Atkinson Traveler are also spruce, though many choose a mahogany, cherry, or walnut outwales. If a hardwood is chosen for the outwales, it is also used for the thwarts, decks, and hand-woven caned seat frames—otherwise ash is the standard wood used. The weave of #10 mildew- treated canvas is filled with an oil-based sealer and usually painted in its entirety; many opt for the traditional finish of shellac below the waterline, which slides over rocks and is easier to maintain than paint. Brass stem bands protect the white-oak stems at the bow and stern.

The heart-shaped decks and hand thwarts date back to the earliest wood-and-canvas canoes, as does the hollowing out beneath the deck. Rollin first observed these features while restoring E.H. Gerrish boats and was drawn to their aesthetics. He likes to include hand thwarts to give paddlers a ready handhold for carrying that dissuades them from using the deck to lift the canoe.

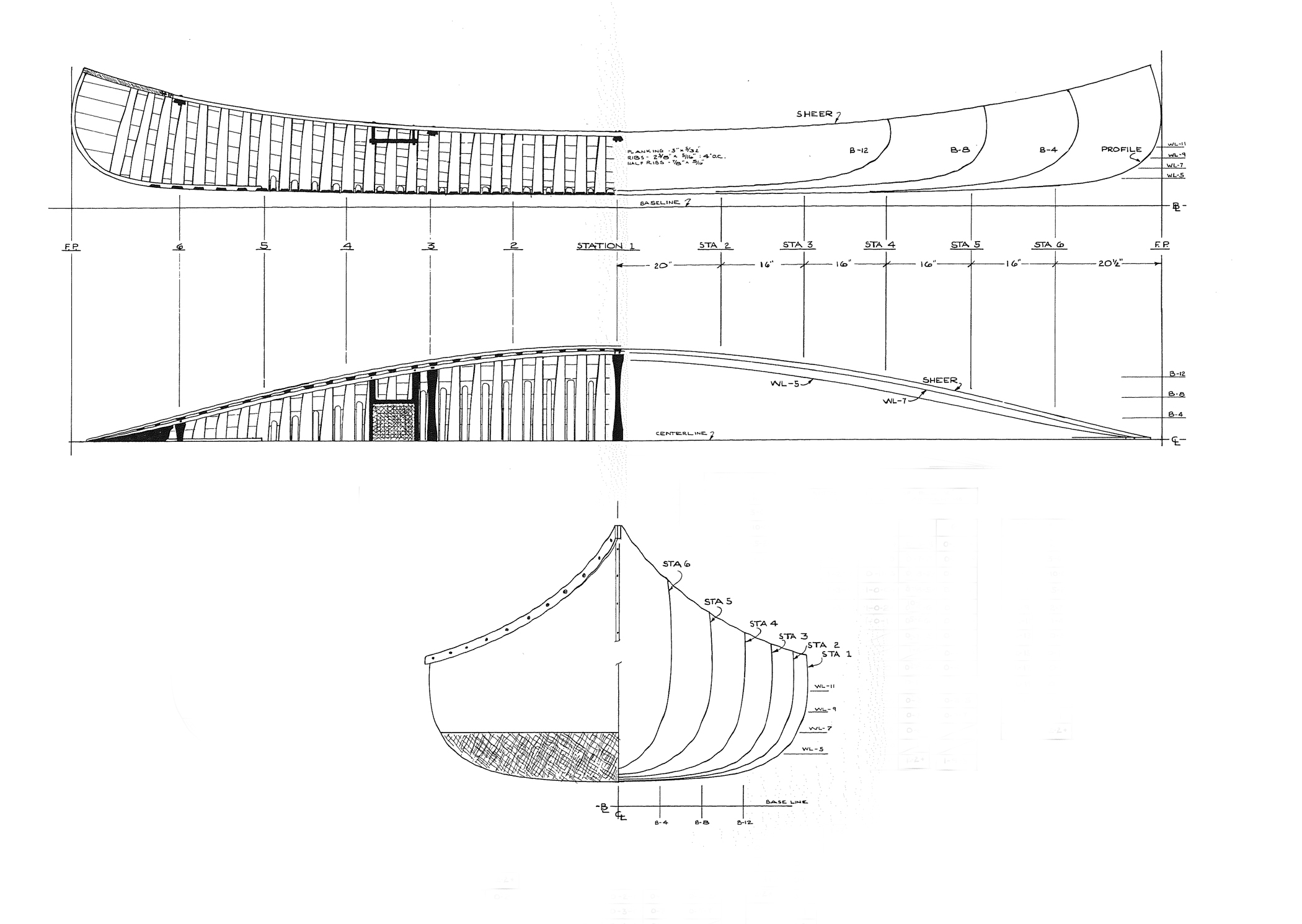

Rollin has sold about 400 sets of plans for the Traveler and highly recommends that homebuilders take the time to build the requisite mold—a sturdy hull form akin to a very heavy strip canoe. Steel bands are attached crosswise over the mold and used to clench the tacks that fasten the planks to the ribs. The hand tools required, include a clinching iron, canvas pliers, a tack puller and a small carpenter’s hammer with a 7-oz head. Builders will need to be set up for steaming ribs, and a jig is necessary to bend the stems. The average homebuilder takes years to complete a wood-and-canvas canoe.

On the water, my paddling partner is Elisa Schine who has worked in Rollin’s shop since 2013. I’m immediately struck by the boat’s speed and a lightness that slices the water and gives it lasting glide. The varnished cedar ribs and planking radiate warmth in the morning sun. The hull is stable when it needs to be as well as agile within the confines of the small pond.

After planting my knees against the sides of the canoe around where the half ribs end, I warned Elisa that I was going to wobble the boat. I rocked it gently, then more aggressively. The initial stability is not as solid as secondary, but the boat is such a comfort to paddle that I scarcely thought of stability for the remainder of the outing. We leaned in and practiced gradual arcing turns and spun it around with hard draws; the Traveler does it all with élan. When I poled the Traveler solo it held a line, even with the bow unweighted and thus a tad high.

Elisa says of the Traveler: “It’s a pleasure to build. With a lot of the models we build, it’s challenging to put planking on ribs, but with the Atkinson Traveler the planking lays across the ribs with no problem.” She believes that Rollin’s expertise unites aesthetics with function. “What looks good to Rollin is going to be the best design as well.”

Rollin has a long history of sharing his designs and hires young builders so he can pass along his knowledge. He has licensed his Atkinson Traveler design to a handful of builders, among them Jeanne Bourquin in Ely, Minnesota. She has been building the Atkinson Traveler since the 1990s and believes the Traveler is “as close to perfect as possible.”

Rollin mentioned that Becky Mason has paddled a Traveler. Becky, the daughter of legendary paddler and filmmaker Bill Mason, is a highly accomplished paddler and filmmaker in her own right, and has introduced thousands to canoeing through her teaching. Like Conover, she holds the Traveler’s capacity in high regard: “You just load those babies up and they take any weight possible. You get elegance—it’s so superbly designed. You get speed—it’s like a dart through the water. And you get maneuverability—it spins on a dime. You can do a beautiful canoe dance or swerve and miss a rock or back it up if you don’t like what you see. When it’s empty it handles like a little acorn on the water.”

“They’re works of art,” says Becky. “There’s an unexplainable quality. You can recognize a Rollin Thurlow canoe, just as you can a Leonardo da Vinci or a Van Gogh.” The subtle attention to detail—the beautiful hollowing along the underside of the deck, the tapering of ribs as they reach the gunwales, the sweep of the bow and the hand-painted waterlines—marks Rollin’s work as that of a true craftsman.

Many see Mason as the custodian to one of Canada’s most hallowed tripping hulls, the Chestnut Prospector, a design her father praised. She paid Rollin’s design the ultimate tribute: “I really think the Atkinson Traveler is an American version of a Prospector,” she says and adds with a laugh, “That’s a bit blasphemous, but I think the Traveler is just amazing.”![]()

Donnie Mullen is a writer and photographer who lives in Camden, Maine, with his wife Erin and their two children. He wrote about paddling the entire length of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail in our February 2016 issue. His article “Investing in Memories: Canoe Camping in Northern Maine,” appeared in our September 2015 issue and he reviewed the Original Bug Shirt in our August 2015 issue.

Atkinson Traveler Particulars

[table]

Length/17′ 5″

Beam/35.6″

Depth/13″

Bow height/24.3″

Weight/75 lbs

[/table]

The Atkinson Traveler is available from the Northwoods Canoe Company and priced at $4,200. Plans and a variety of kits are also available.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Great article! I paddled wooden canoes as a camp kid and ‘glass as an adult. The wood has a feel that ‘glass can’t match. I suspect that many of the wood boats I paddled were held together by the yearly coat of green paint they received.

I have never seen a paddle held that way. Please tell me more!

A wonderful article. These canoes are truly works of art—form meets function—and beautifully constructed. It’s nice to know that Rollin is passing on his knowledge to the next generation of builders.

The Northwoods Paddles Rollin and Elisa are using are carved by Alexandra Conover Bennett. I used one when paddling the Traveler and found it powerful, a perfect match for Rollin’s boat. They are generally made from ash (though cherry and maple are possibilities) and run 5′ to 6′ in length. The staged grip allows the paddle to be effective in both high and low water. One can also use it to practice the Northwoods Stroke. Its design is traditional to the region. Honestly, I’ve wanted one for a long time.

For more information on any wooden canvas canoe or the paddle designs and techniques shown in the pictures please check out the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association. There is a large forum section discussing many topics about wooden canvas birchbark and all wood canoes.