Beyond Cairo Point, the eastward-turned tip at the bottom of Illinois, the Ohio River poured into the Mississippi, but the collision of the two great rivers only crumpled the surface of the water and spread ripples across the mile-wide confluence between Missouri and Kentucky. It was December 7, 1985. The cold front that had surrounded LUNA with ice that morning had cleared the sky and the sun had raised the temperature a few degrees above freezing. The Lower Mississippi, easily twice the breadth of the Ohio, pulled me toward a breach in the horizon where the umber-hued woodlands hung cantilevered over the river’s reflection of clouds.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorAbove the toe of my left boot is a bridge over the Upper Mississippi River; above the right boot is a bridge over the Ohio River. The low land between the bridges is Cairo, Illinois.

I rowed in midstream where the current was the swiftest and to give a wide berth to what was the first of a series of seven dikes, or wing dams, that the chart showed would be coming up on the Kentucky side, the longest reaching two-thirds of a mile from the shore. There were no wing dams on the Ohio, but the Mississippi has thousands of them. The rows of piled boulders set straight out from shore force the current into the navigable channel, speeding it up so that sediment doesn’t settle. I didn’t know what to expect, and before I saw any sign of the first wing dam, I heard a sound like wind rushing through a thicket of aspen. Carried on a breeze blowing upriver, it was clear and crisp, making the dam seem both close and dangerous, but when I passed it, the dam was covered by water so deep that there were no standing waves trailing it, just a patch of sharp-cusped ripples spilling across one another.

In the vaulted sky was a miscellany of clouds, some like rippled sand or fish scales, others billowed, flat-bottomed, or bearded with virga. As the sun angled toward the horizon, the colors illuminating the clouds changed as rapidly as their shapes and patterns did.

I’d rowed 23 miles from my last camp on the Ohio River to get to the confluence and after rowing another 10 miles it was getting late in the day, so I pulled ashore and made camp on a 3⁄4-mile-long sliver of an island near Millers Landing on the Missouri side of the river.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

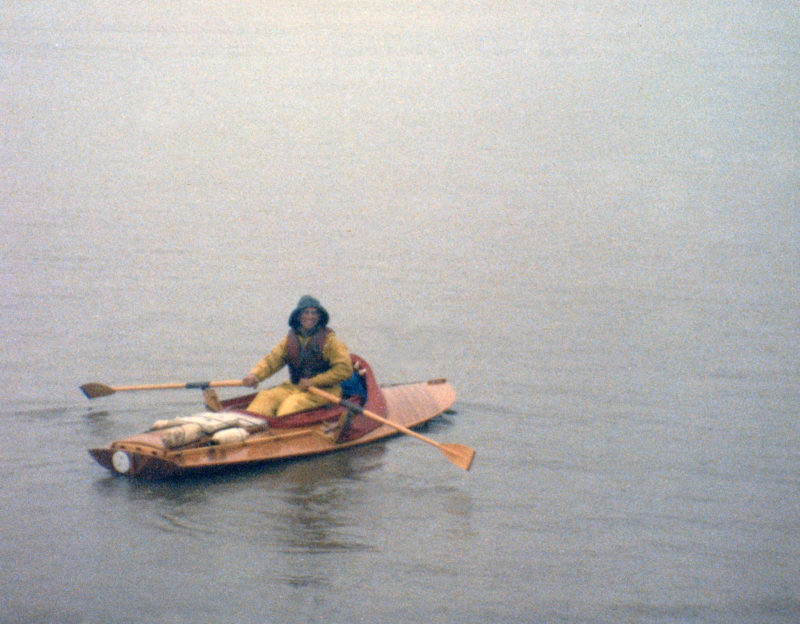

In the morning I was fogged in and everything but the sand and brush within 20 yards of my campsite had disappeared. It was too risky to row—the swift current would push me too quickly toward hazards to avoid them. I’d also be invisible to vessel traffic—sitting so low in the water and having very little metal aboard, LUNA wouldn’t show up on radar.

I spent part of the morning writing letters and did some work on LUNA’s oarlocks. While they were as good as new when I left Pittsburgh, the month of rowing down the Ohio River had enlarged the holes in the oarlock sockets and made them egg-shaped while the shafts of the oarlocks were no longer straight but tapered from the middle toward both ends, the metal polished to a bright shine by the wear. I had been applying grease to the locks several times a day, but the horn and the sockets had worn through almost 1⁄8″ of bronze between the two bearing surfaces. I unbolted the sockets from the oak stanchions and rotated them, as one would the tires on a car, to have their unworn sides take the burden of rowing.

When the fog lifted, I headed downriver and made good progress—easily 6 mph with the help of the current. For 5 miles the right bank was lined with riprap, the rocky upper fringe of a revetment almost fully concealed by the high water. Most of the revetments were along the banks on the outside perimeter of the bends in the river, and the wing dams were on the opposite banks. The Army Corps of Engineers had been charged with installing and maintaining all this stonework in 1928 after a prolonged heavy rainfall in 1927 flooded much of the river plain. The Mississippi now caroms off the rockworks of this man-made corridor. The fastest water was on the revetment side of the river, so that’s where I could make the best speed. The wing dams had slow-moving water and collected sand, which made good beaches for landing and camping.

The Lower Mississippi’s many islands and sand bars provided easy places to come ashore for a midday break or to camp.

At dusk I coasted along a bend that led the river northward, and looked for a campsite. The left bank was lined with revetment. Where it ended, I pulled ashore on a gentle slope of tawny sand and made my camp at the edges of a cornstalk-littered field on Kentucky Point. The point is a lightbulb-shaped lobe of land wrapped by a great loop in the river. To the south, the Mississippi comes within 3⁄4 mile of folding back on itself. At the apex of the 19-mile loop is the city of New Madrid, Missouri, which relies on the levees to prevent the river from straightening itself, leaving the town stranded on the banks of an oxbow lake.

I often passed the time between dinner and bedtime watching the tows go by. Tow tugs operating after dark swept their spotlights along the shore to negotiate the bends in the river and sometimes illuminated my campsite.

To the north of my camp a tow’s bright spotlight glowed through a lattice of leafless trees like the rising of a full moon. Its beam slipped off the smooth surface of the river, leaving no mark other than the firefly glints of bubbles and flotsam.

In the morning the air was still as I rowed to the outside of the bend where the rush of water over the bottom made the sneakbox’s resonant hull hiss like a punctured tire. In the still air the only marks upon the water were patches of froth marbled white and tan and the dimples of tiny whirlpools that spun like ball bearings between opposing flows of water. I secured LUNA in the brush at the New Madrid riverfront and walked to the top of the levee. A man in a pickup truck driving along the crest of the levee had seen me come ashore and pulled up alongside me. “Boy, don’t I know how it is when your motor breaks down,” he said. I asked if there was a grocery store nearby, and he gave me a ride into town to the local market. Two young women working there found me interesting, probably because I was the scruffiest customer to walk through the doors. When I got to the register, one said, “Did you just get off a boat?” I answered, “Yes, I must look awful.” She replied quietly, “Yes, you do.”

When I had finished shopping, the man with the pickup truck was back in the parking lot waiting for me. He had driven to the levee to take a closer look at LUNA and then come back to take a second look at me and give me the return ride. There were some advantages to not blending in.

By the time I rowed past Kentucky Point’s slender waist, I was 2 miles along the Tennessee shore on the left bank and the warm midday air was filled with gossamer, some so fine that I saw only briefly a bright iridescent thread as it refracted the sun’s light before vanishing. The more substantial strands drifted with the wind like strings trailing errant kites.

I didn’t see as many towns as I had along the Ohio, and the land hemmed in by the levees, broad expanses of leafless trees and pale sand, gave the Lower Mississippi the appearance of a remote wilderness. I stopped at the site of the old Tiptonville ferry landing on the Tennessee side where the levee rose directly above the riverbank. From the top I could see the land on the other side. Close by it was flooded, but beyond that, stretching uninterrupted to the horizon, were fields radiant with still-green crops, laced with windbreaks of poplars and a web of roads, and dotted white and red with houses and barns, steepled churches and clustered grain silos, as different a world from the river as Oz from Kansas.

After rowing 42 miles downriver from New Madrid, I stopped for water at Caruthersville, and parked LUNA on the town’s concrete boat ramp. Two blocks into town I passed a wedding reception—the matching bridesmaids taking a stroll in the sunshine were the giveaway—in full swing at the local bank and on the sidewalk around it. I stopped at a women’s clothing boutique across the street. At the register there were three women working, and it seemed I had caught one of them off guard. She looked at my hair (which I knew had some interesting angles to it from the glimpse I had caught of my reflection in the shop’s window) and made a slow scan of the grime from there down to my boot. When I said, “Hi!” she snapped her gaze to meet mine and looked a bit embarrassed that she had forgotten her manners. “Well,” I said, “am I the best-dressed man in town?” and got a smile in reply. I asked if I might fill my water jug, and she led me to a sink in a back room. I thanked them as I left and, after I’d walked out the door, I heard them all giggling.

While much of what I’d read about the Lower Mississippi described it as a dangerous river, I found it mostly tranquil and well suited to traveling in my very small boat.

I spent the night camped a few miles downriver from Caruthersville, and the following day I arrived at Chickasaw Bluff No. 1, the first of four. The tawny cliff of ancient, compacted sediment towered 300′ over the river and shunted the course of the river from southeast to southwest. Ten miles farther downriver I approached Bluff No. 2 and stopped rowing to study what lay ahead. The Mississippi takes a sharp westward bend from south-southeast, tighter than a right angle, and squeezes its width from 1 1⁄4 miles to 1⁄2 mile. It was not an easy turn for the tows—towboats pushing as many of 42 barges, each measuring 195′ by 35′, all rafted together.

The Chickasaw Bluffs on the Tennessee side were imposing features and Chickasaw Bluff #2 required downriver tows to make a surprising maneuver to negotiate the river’s sharp turn at its base.

A tow coming downriver passed me, veered perpendicular to the current to drift toward the bluff. When the tow was just shy of impact, the towboat accelerated straight into the westward leg. I followed well behind the tow, taking roughly the same line. The river bunched up and flipped wave crests into the air, but at the base of the bluff was a smooth upwelling. Water from the bottom of the river apparently curled up at the submerged base of the cliff and created a countercurrent cushion that pushed LUNA safely away. The high banks streaked by too fast to focus upon them as I bounced through standing waves and dipped into the edges of the whirlpools that trailed from the downriver edge of the bluff. On the downstream side of the bottleneck, I darted over a mound of water between two whirlpools and pulled into the back eddy. In its quiet eye I waited for the tow that had been gaining ground on me in the previous reach of the river. The rusty bow of its lead barge clipped by the edge of the bluff and squeezed through the narrows. After the throbbing tow tug had passed, I drove the bow of the sneakbox back through the eddy and into the turbulence and raced downstream with the full force of the current behind me.

The couple who took this photo of me arriving in Memphis introduced themselves at the marina and took good care of me during my stay in town.

Chickasaw Bluffs Nos. 3 and 4 were not nearly as dramatic: No. 3 was an unremarkable hill hidden by a forest, and downtown Memphis concealed No. 4. At Memphis, I rounded Mud Island and rowed into Wolf River Harbor. A local couple, Lauren and Gayle, had seen me coming in and met me after I landed. They saw to it that the harbormaster provided me with a slip where LUNA would be safe and took me (by way of Elvis’s Graceland estate) to their home where I ate well, did my laundry, and slept in a comfortable bed.

I usually passed the big cities by, making only brief stops for supplies. In Memphis, two strangers welcomed me into their home. Here LUNA is at rest in the middle of the far pier at the bottom of the launch ramp.

Before I left Memphis, I’d met a man who had taken an interest in the sneakbox and what I was doing and offered to put me up for the night. We’d rendezvous 28 miles downriver from Memphis at Star Landing, just the other side of the Tennessee-Mississippi border.

As I rowed downriver, I passed a beach on the left bank that would have made a good campsite but I gambled on the promise of a hot shower, a home-cooked meal, and a warm bed. I was still 2 miles from Star Landing when the sun set, and it was nearly dark when I reached the location marked on the chart. It was a landing in name only; the bank was covered with a revetment of broken boulders. I kept moving with the river; the sharp-edged revetment continued for as long as there was light to see it by.

With the dark came cold: 15 degrees below freezing. Spray blown by an upriver breeze came over the bow and gelled in a lumpy sheet of ice on the foredeck and glazed the canvas dodger. Beads of ice stuck to the back and arms of my jacket and blunt icicles sprouted from the oar looms. A waning moon rose over the bank as I searched for a landing of sand, but in the shadow of its glow, the shore and river merged in black. Tugs working their way upriver swept mile-long blue-white searchlight beams along the shore. I hoped that they would not see me; if they focused their lights upon me, I would be blinded by the glare. As the current carried me over submerged islands of brush, leafless stalks came out of the dark and whipped against the hull and oars. My face was raw with the ice-edged wind and my feet had been numb since sunset.

Nearly three hours into the night, the silhouette of trees along the bank thinned and lowered. I crept in close where the beam of my flashlight could distinguish between the river’s rim of ice and any patches of sand. Behind an inundated row of grass tufts, I spotted a 6′-wide pocket of sand. The grass, frozen solid, did not give way when I plowed the bow into it. I backed and rammed it a second and third time before I scraped through and beached. I tied the painter to a branch and immediately gathered wood for a fire. I needed warmth and couldn’t waste time setting up the tent. My teeth were chattering so violently that I kept my mouth open to keep from chipping them. After the cold moved in from my arms and legs and reached my core, spasms gripped my midsection, making me grunt as if I’d been punched in the stomach. I got the fire going, fed it with twigs and driftwood until the heat seeped through my jacket and into my chest and arms.

In the middle of the night, long after my stomach had lost the warmth of dinner and the bottle of hot water in the foot of my sleeping bag had chilled, I lay awake and waited for morning.

In the morning, the ice that had coated the boat had not yet melted. Note the pool of solid ice at the base of the oarlock stanchion.

I didn’t get up at first light but waited for the sun to rise above the levee to the east and illuminate the tent. I stepped outside and got my first good look at the frost-dappled shore where I had landed. The patch of sand that I’d camped on was backed by a field of cobblestones, dark and wet with melted frost. In the middle of it, a dozen yards from the tent, stood a single leafless tree less than twice my height. Its shadow had kept the frost from melting, and the silhouette cast over the stones was a filigree of glistening white frost.

At Helena, Arkansas, I stopped to pick up mail. As with most stops in towns, I ran to minimize the time the boat was untended. The sidewalks of Helena were cracked and uneven; a protruding lip of concrete caught the toe of my rubber boot, and I was suddenly horizontal and airborne a good 3′ above the sidewalk with time enough to think about my landing. Pancaking on the concrete would spread the skin of my palms across the sidewalk like cold butter on lukewarm toast. That would put an end to rowing for a while. The previous summer I had learned how to fall and roll in an Aikido class and decided to use that approach for my landing. I curled one arm down from my Superman stretch and hooked it under my chest. When the outside edge of my hand made contact with the pavement, the rest of my body curled downward onto the concrete and rolled without skidding. (That evening I wrote a letter to my Aikido instructor thanking him for a self-defense technique that defended me from myself.)

At the post office I picked up two packages and several letters. My mother had sent a wool shirt long enough to tuck into my pants. My sister had sent a red polypropylene balaclava that made me look like a cloth doll with a ceramic face, but it was warm. I now had protection in the two spots that had always been vulnerable to the cold.

I camped at the Sunflower Cutoff, one of many places where the Mississippi had once served as an established border between states before its course was altered by flooding or by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The border didn’t move and often left bits of one state on the “wrong” side of the river. At mile 625 (measured from the Head of Passes on the Mississippi River Delta) there used to be two great loops, the upriver one curving out and back 11 miles to the west and the downriver one 13 miles to the east. The Jackson Cutoff and the Sunflower Cutoff were dug by the Corps across the loops in 1942. The river began to flow through the new channels, but vessels still had to navigate the old route around Jackson Point (which became Island 65) and Island 66 until the cutoff was deep enough. In the years that followed, the old channel accumulated sediment and both of the islands joined the land that surrounded them, and neither is an island now. They are still marked on the charts as islands, 65 as Mississippi land in Arkansas and 66 as Arkansas land in Mississippi. All of the cutoffs combined have shortened the Lower Mississippi considerably since Bishop rowed it in the winter of 1874: it was 1,150 miles then; 953 miles now.

On December 17 I rowed 50 miles. The Mississippi River runs faster than the Ohio, but it’s more difficult to take advantage of the current. Sometimes the fastest flow wasn’t where I thought it would be, and I often wound up in slack water or back eddies. The wind had also been contrary most of the time, and I expended a lot of extra effort dodging tows.

The confluence with the diminutive Arkansas River was much choppier than the merging of the Ohio River at Cairo.

I made a short stop at Terrene Landing, an unpaved boat ramp in the middle of the woods on the Mississippi side, then on the right bank rowed by the mouth of the Arkansas River where its current crumpled the Mississippi up against the left bank. Chaotic waves popped up so steep that froth slipped hissing down the upriver faces. LUNA surged through the buckskin-brown chop, dropping off the crests and hammering her bow in the troughs but carrying me through dry.

At the end of the day, I pulled LUNA out at the Caulk Neck Cutoff. A truck driving on a road at the crest of the bank stopped. I walked up and met a man named Fred, who explained that the land here was the property of a private hunting club. I could see that it was a fancy one with an airfield across the road, two private planes, and a large lodge, which Fred said was “four or five hundred thousand dollars’ worth.” I told him I was hoping to get off the water for the day. “We’ve got some cabins a ways up the road you could use.” I didn’t want to get far from the sneakbox, and thanked him for the offer.

I shoved off and passed beneath the lodge on its perch at the edge of the bluff. A woman on the porch waved at me and went inside; a crowd of people at the window turned to watch me. I crossed to the river’s opposite shore and landed on one of the sandy beaches on an island called The Bar. As I gathered driftwood for a fire, I could see the lodge all lit up and filled with people who I imagined were sitting down to an elegant dinner of venison, duck à l’orange, and focaccia. I was content to heat a can of beef stew, spread peanut butter on a squished slice of bread, and dine next to a warming fire under a half moon and a star-strewn sky.

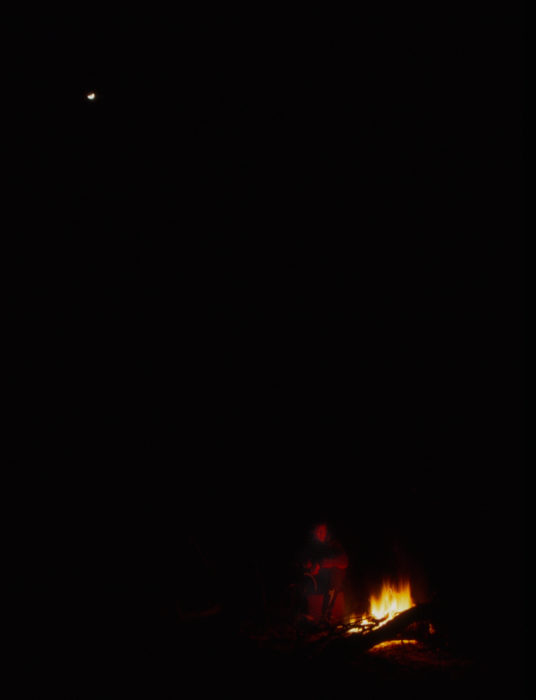

Most of the Lower Mississippi was far from any towns that would keep the sky lit all night long. The half moon and campfire kept the darkness at bay.

While I was setting the tent, still icy from last night’s frost, I listened to the weather radio. Another “mass of Arctic air” had crept across Canada and was headed my way. For the moment, the air was only cool, and I was warm; my shirt and jacket smelled like they had just come hot out of a dryer. I had burned most of a whole driftwood tree during the evening, and I let the flames retreat into the circle of embers before turning in.

There had been no frost in the morning and the tent fly wasn’t even damp so my hands wouldn’t get so cold breaking camp. I made good speed toward Greenville, Mississippi. In the last bend before reaching the town’s waterfront, I was taking advantage of the swift midriver current, making good progress, though it was always hard to know how much of that speed the river was adding. I looked over my left shoulder to check my course, and in the moment that I had my head turned, a red nun buoy, which had been pulled under by the current, erupted from the water just two boats’ lengths away. Its top rose 6′ above the water and the buoy came to rest, angled sharply upriver, and passed by me as if under power, with froth wrapping around it.

It was a red nun buoy like this one that shot up out of the river close to LUNA on the run into Greenville.

Greenville was once on the left bank of the Mississippi River on the downstream end of Bachelor Bend, but in 1933 the river cut across a narrow neck of land and bypassed the town. What is left of Bachelor Bend is now Lake Ferguson, which opens onto the river. It would have been a 4-mile row for me to get to the center of town, a chore I wanted to avoid. I pulled LUNA into the brush by a grain elevator, walked to the road, and put out my thumb. My appearance may have put off the first several drivers. It was cold and windy, and I walked about a mile before a man in a truck picked me up. He asked what I needed and bypassed his usual route to drop me off in front of the post office. After mailing the letters I’d written, I walked to a grocery store, hurried through the aisles dropping the usual staples into the cart—Fig Newtons, bread, cheese, apples, Grape-Nuts, crackers, V-8, beef stew—and a new item, canned barbecued chicken.

I hadn’t approached a local newspaper to offer my story for a while, and called the Delta Democrat-Times. A reporter named Alice met me in town. She got her story and photos, and I got a ride back to the boat.

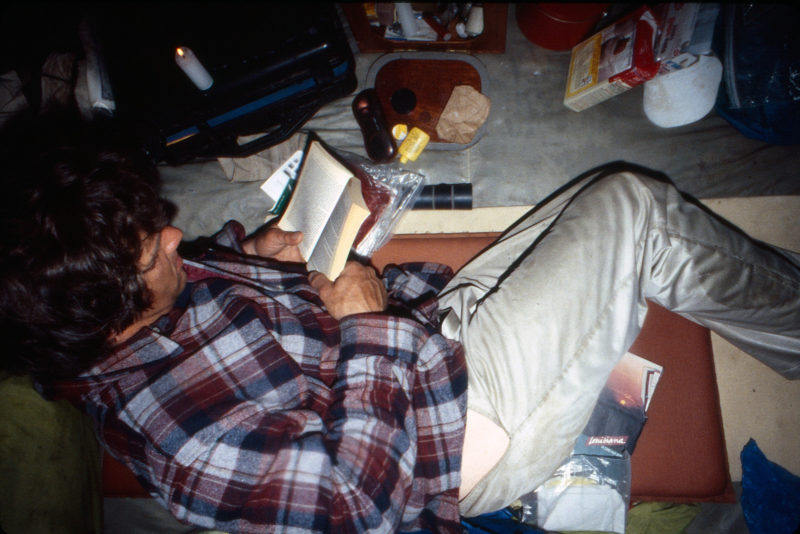

I didn’t have to spend nights on board the sneakbox as I had on the Ohio River. Instead, I had plenty of space in my three-man dome tent to relax during the long evenings.

I rowed out the channel to get back on the river, where the wind had dropped a bit but was still good for a shove, and 10 miles downstream I arrived at a nameless island at sunset. Its upstream end was a long, low point of white sand. As I stood on the beach looking for a good place for the night, windblown sand whirled around my boots and made small dunes in their lee. Farther downstream I came ashore again near a small cluster of trees that would provide the tent protection from the wind. I set up camp as the last crimson light of the day bled into night. In a fire made of driftwood from the beach and dried limbs from the woods I cooked a can of beef stew. After dinner I was ready for sleep and filled the cookpot with river water to soak. I’d wash it in the morning. It was a cold night, but in the tent’s bubble of still air I slept well.

Retrieving my spoon from the solid block of ice in my cookpot would take a bit of effort. Melting the ice on the stove would consume a lot of fuel, so I had to chip it free.

When I emerged from the tent in the morning, I saw that the water in the pot had frozen solid. Through the lens of ice, I could see the silvery shimmer of my spoon against the carbon-crust remnants of last night’s dinner. As I dismantled the tent, I shook the ice from it. Flakes of ice fell from the inside walls, and the frost on the outside rose in a cloud of white powder. I stuffed the tent in its bag with bare hands to keep my gloves dry. The painter, strung taut between LUNA’s bow and a tree, was rigid with ice. I bent it into a coil of irregular triangles and set it on the afterdeck with the cookpot to thaw during the day’s rowing. Out on the river there were small patches of ice that were invisible until the waves in my wake lifted their edges. Clumps of brown river foam, as stiff as baked meringue, fractured when I hit them with the blades of my oars.

On a day that was so cold that my boots didn’t keep my feet warm, I put on extra socks and grocery bags.

I usually warmed up after rowing for a while, but as I traveled south from Greenville, my hands and feet stayed cold. I couldn’t do much about my feet with my rubber boots on. I took them off, put on another pair of wool socks, and put grocery bags on over them. I had brought pogies to keep my hands warm, but they were cumbersome when I had to switch from rowing to the many other tasks on board, so I wore my gloves.

North of Vicksburg, an olive-drab aluminum jonboat skimmed across the river to LUNA. The skipper, Dan, had been hunting ducks, and the limp bodies of a dozen ducks were lined up on the thwart ahead of him. For 4 miles we drifted together holding onto one another’s boats. The conversation turned to the history of the area. The Civil War had ended only a decade before Bishop rowed the Mississippi, but Dan talked about it as if it had ended last week. His face flushed red with anger about the calumny of the Yankees as we passed the wooded point where Union troops had come to do battle. He pointed across the river to the woods on the left bank. “Over there, Grant, the plodder, tried bringing his gunboats down the bayous. Course we was ready for him with guns around every bend. BOOM!” He motioned downstream where Grant tried to reroute the river around the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg. He pointed to the opposite bank where Confederate guns fired upon Union soldiers as they labored in vain over their diversion canal. “BOOM, BOOM!” Dan’s cannon shots echoed in the woods along the shore.

Within a year of Bishop’s rowing by Vicksburg, a flood did in hours what General Grant’s troops could not accomplish in three months, and the Mississippi cut a new course. Vicksburg was left on a stagnant reach of the old riverbed. Soon afterward the Yazoo River was diverted to keep Vicksburg’s harbor open to the Mississippi.

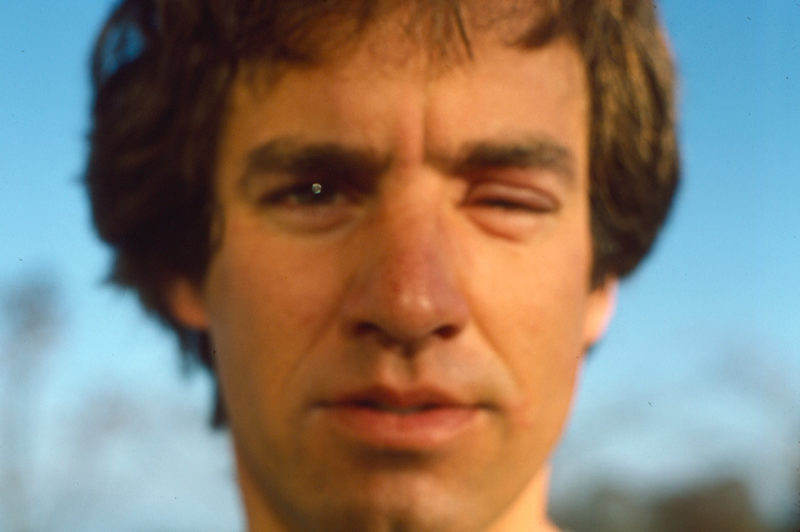

The gloves I’d lent to a volunteer on the Ohio River came back to me with an invisible coating of poison ivy oil.

During the cold spell, something was going wrong with my left eye. It was very itchy, and my eyelid had swelled up so much that it was in a permanent squint. I stopped at a fuel dock on the right bank and explained my problem to the woman working there and asked if I could use the restroom mirror to take a look at myself. I looked a bit like I’d been in a fight, but I only had the swelling, not the bruising of a black eye. When I got back on the river it occurred to me that my gloves were likely the cause of the problem. At Payne Hollow on the Ohio River, I had lent them to a young woman who had been part of a crew cutting firewood for Harlan and Anna Hubbard. She must have pulled poison ivy off the logs. I had evidently been rubbing my eye with my gloves on and had gotten the poison ivy oil on my eyelids. I hadn’t been taking my gloves off when I had to take a leak either, so my eye wasn’t my only problem.

Christmas Day called for dressing in red—balaclava, pogies (rowing mitts), and spray skirt—and hanging a red wool stocking.

On Christmas Day, I stopped early to give myself time to set up a comfortable camp and relax for an afternoon. I found an island of sand and willows with a high perch for my tent with a clear view across the river. The sky was cloudless and the air still, and there wasn’t another person or a sign of civilization in any direction. And I was, as the Germans put it, wunschlos glücklich, wishlessly happy.

Fourteen years earlier, I had done my first solo backpacking trip at the age of 18. Since then, I had increased the challenges of my wilderness adventures, hiking farther, staying out longer, and graduating from summer to winter travel. I was driven to see not only what I was capable of but also if I enjoyed my own company. I continued on that same path with boating, and my cruise with LUNA was the culmination of 14 years of making my way under my own steam. None of the challenges I’d faced on the Ohio and the Lower Mississippi had ever made me wish I were anywhere else. On the bad days I had persevered, on the good days I sang.

As I drew near to Natchez, I had another jonboat encounter. Two of them buzzed up to LUNA; the first skimmed by, the second slowed down and passed alongside. There were three camouflage-clad men aboard about my age. I said, “Hi.” The helmsman replied, “You’re the craziest thing I’ve seen so far.” With a smile I countered, “I haven’t said two words and you’ve already decided that I’m crazy. It’s hardly fair.” That got him laughing. He promised to meet me at Natchez and buy me a drink before he zipped away. I stopped in Natchez for supplies and mail but never saw my jonboat acquaintances. On my way downstream, just past the Natchez-Vidalia Bridge, I rowed past a barge that was sticking up in the middle of the river: 175′ of it underwater, resting on the bottom, and 20′ angled up over the water.

The Lower Mississippi has no locks to restrict the number of barges in a tow. There can be as many as 42 rafted together—seven rows of six barges side by side—covering an area of nearly seven acres. Occasionally one gets loose, like this one just downstream from Natchez, and is lost.

For the next 26 miles there was nothing more to see than winding riverbanks blanketed with trees, a landscape I imagined was unchanged from what Bishop had seen 110 years earlier. I stopped for the night on the left bank of Dead Man’s Bend. Before I set up camp, I walked through the woods at the water’s edge to see what was in my new neighborhood. I found a shack high overhead, perched on 20′ stilts. It was built on the outside of the bend where tapered ridges of sand, left by rushing high water on the downstream side of every tree, looked like drifted snow.

I set my tent on a spot of high ground where a knot of trees held the soil together with the mesh of their intertwined roots. In the logjam heaped against the trees there was plenty of bone-white driftwood for my campfire. A white plastic bleach jug was lodged in the pile, and I brought it back to camp. I cut slits arranged like a capital H in its side, bent back the two flaps, and set a candle in the jug held to the bottom by a drop of hot wax. With the candle lit, the jug glowed like a fluorescent light bulb and, with the luxury of bright light, I spent the evening answering the mail I had picked up at Natchez.

The winter days were short but having fewer hours of daylight kept me from expending too much energy rowing and gave me time to enjoy sunsets over the river.

There was a thick cloud cover in the morning, and after I rowed 2 miles from camp I was in the fog. I kept going, but when I strayed too far from shore the banks disappeared, and without that reference it was as if the river had stopped moving and LUNA had been brought to a crawl. When I heard the throb of twin diesels of commercial traffic in the channel, I hurried back to shore. If the tows were moving, the fog was close to the ground and the skippers had a clear view from their wheelhouses, three stories above the river. I rowed the inside of Graham Bend, which wasn’t as slow as it could have been because an island hooked a lot of current to the inside.

Below the bend it was quiet, and I headed across the river into the fog. I thought that I’d be able to see the opposite bank as the one I left behind disappeared, but I soon reached a point where I could see nothing. I kept the wake trailing behind me as straight as I could, but I was still anxious. I scrambled for the compass in the seat box and pulled due west; I came up to the right bank quickly. After 27 miles I put in at the Fort Adams Landing, at the foot of a bluff, and discovered that many deer carcasses had been dumped over the bank. There were hooves and heads poking out of the sand, ballooned entrails, and white sheets of waterlogged hide. A fresh carcass in the water was wreathed in red. It had been raining most of the morning and my clothes were soaked, but this wasn’t a place where I wanted to stay to get warm.

I crossed the Mississippi state line into Louisiana and rounded the 9-mile bend that curves around Angola, the Louisiana State Penitentiary. I kept to the far bank. At the next meander, Tunica Bend, I heard an upbound tow through the fog. I stayed close to the right bank, and after it had passed and was so far away and so quiet that I would be able to hear any other traffic, I headed across. In midstream, I emerged from the fog bank and saw a church and a few buildings on the left bank, an unusual sight because, aside from the bluff cities and settlements, so much was hidden behind the levees.

The Como Plantation was a ghost town. But, while it seemed abandoned, there were no signs of vandalism so someone must have been taking care of it.

I pulled LUNA out on a sandbar downstream from Como Bayou, which was a creek I could almost jump over, and walked through the woods toward the church. A hard-packed dirt road led across a wooden bridge spanning the bayou to a gate where a sign said that this was the former Como Plantation, adjacent to what was once the river port of Brandon. The white clapboard church had a belfry capped by a small cross. Inside, it was gutted and empty except for a pile of large cardboard tubes for molding concrete piers.

The uninhabited Como mansion was an elegant building influenced by ancient Greek architecture.

Across the road were a general store and a brick-fronted Bank of Pointe Coupee, both empty. A few dozen yards from the church was the mansion of the one-time plantation. It had a clapboard piedmont supported by four slender fluted columns, two stories high, with Corinthian capitals that each had three tiers of curved leaves.

On the Ohio River, I didn’t have a single campfire. The Mississippi, with its sandy beaches and abundance of driftwood, offered the luxury of warmth at the end of a cold day.

The rain had eased to a drizzle but was still falling, so when I returned to the river’s shore, I stretched my tarp between two trees above the beach, set the tent under it, and got a small fire going to dry out my pants and other wet clothes. As a treat, for dinner I had two cans of beef stew.

I was up early and underway quickly—it was a Saturday and I wanted to get to the St. Francisville post office, 26 miles downriver, in time to pick up my general-delivery mail. There were a few cars and trucks, some occupied, in the landing’s parking area at the end of the road that led to town, and I wanted to leave LUNA in a less public place. I rowed up Bayou Sara, past a few derelict tugs and wrecks that were hauled half up on the banks, and came to a launch ramp that looked like a safe place. A mint-green pickup that I had seen near the ferry landing drove up and stopped at the top of the ramp. After I had tied LUNA to a tree trunk, I walked to the truck and the driver rolled down his window. “Didn’t I see you back at the landing?” I asked. He nodded, and we introduced ourselves. Johnson was waiting for a friend to come back in from duck hunting, but he had some free time and offered to take me to the post office. The post office, as I’d feared, had closed at 10 a.m., but Johnson’s mom had worked for the postmaster, Miss Clara. We drove to Miss Clara’s house on the edge of town, but she was out. Johnson then took me to a grocery store and parked to wait for me. As I entered the store, I realized that I’d left my wallet in the boat. Annoyed with myself, I returned to the truck, ready to give up. “How much are you going to need?” Johnson asked. I said about $15. He gave me $20.

Near the grocery store was a billboard featuring Rosedown Plantation where tourists could see 120-year-old azaleas. Johnson saw me staring at the sign and said his ancestors had lived there. Johnson was Black.

On the way back through St. Francisville, a well-groomed town graced with well-preserved Antebellum architecture and broad live-oak trees draped with Spanish moss, I asked Johnson if things had changed much in the town over his lifetime. “No,” he said, “it’s just the same. Place is run by Jim Crows. Jim Crows don’t want it to change, so they keep it the way it is. I’m heavy into politics, you know. It’s time for some changes.” He didn’t say what kind of changes, but it was easy enough to guess. His bitterness was well-restrained but evident in what he repeated several times as he drove me back to the boat: “It’s time for some changes.”

When we got back to the ramp, I asked Johnson to wait a moment while I retrieved my wallet to repay him. I appreciated the loan and valued even more his kindness and his willingness to share a glimpse of what life had been like for him in the South.

Eleven miles downstream from Bayou Sara, I climbed to the top of the bluff to a plow-corrugated field. Near a lone pecan tree in the middle of the field, cradled in the soil, I found a lead Minié ball, speckled white with oxides, that may have been fired during the Civil War. Bishop wrote that the bullets gathered in Vicksburg after the war amounted to 300 tons of lead. One-hundred twenty years after the war the harvest of lead still continues and for some in the South, the war has not yet been put to rest.

From Bayou Sara I rowed 24 miles to Solitude Point and set up my tent among trees that leaned precariously over the river. After the sun had set, the glow of Baton Rouge lit up the night sky to the southeast.

Solitude Point was the last quiet camp I had on the Mississippi River. At Baton Rouge the banks were a tangle of steel pipelines, storage tanks, and refining towers hissing plumes of steam. The river strained through the pilings beneath the long loading docks. The depth of the channel increased from 12′ to 40′, to accommodate the oceangoing tankers and freighters that steam 230 miles up the Mississippi from the Gulf of Mexico to Baton Rouge. For a small rowing boat, Baton Rouge was a 5-mile-long gauntlet of wharves, ships, tugs, and barges.

Baton Rouge is 230 miles upriver from the Gulf of Mexico, but it is a deep-water port crowded with ships from around the world, many at anchor, like this ship from Bombay, awaiting their turn at the docks to load or unload cargo.

The air that hung over the river was thick with the smell of diesel exhaust, and there was a constant drone of immensely powerful engines. Tugs backed and filled, their superstructures swaying heavily as they bullied barges into position. The froth of prop wash swirled out white around their sterns. Several of their captains, hard-edged men in visored caps, opened the doors of their wheelhouses to stare at me, and some even pointed cameras my way. One traced spirals in the air at the side of his head with one hand and pointed at me with the other. Another was more direct.

“Are you crazy?” he shouted.

“I must be,” I hollered back.

“Awright!” He jammed a fist into the air.

I rowed a strong, steady pace, churning a wave at the bow that hissed like frozen French fries plunged into hot oil. On the stern of a tug headed upstream, a roustabout with sledgehammer pounded out my cadence on the steel deck.

After I cleared Baton Rouge, there was still wilderness between the levees east and west where I could camp.

The following day I rowed by Plaquemine too early for any stores to be open. I made a stop mid-morning at Bayou Goula, where a church steeple and plantation-house chimney peeked over the levee. I walked 1⁄2 mile along the levee from where I left LUNA. In a neighborhood separated from the plantation manor by vine-choked woods raucous with birds, the houses were in sad shape. Clapboards that had rotted away revealed the backsides of interior walls. Some houses showed traces of paint, but most of the wood siding was bare, gray, and fissured. And yet there were brightly colored curtains in the windows, and the sound of music seeped through the walls. I flagged down a car and asked the driver, a young man, about stores. Without hesitating he told me to hop in and took me to the grocery store and then back to the levee.

About 15 miles downriver from Bayou Goula, I looked over the bow and saw twin flashes of reflected sunlight about a mile away. It had to be another rower, the only one I’d seen since I set out from Pittsburgh. I pulled hard to catch up and closed the distance quickly. The boat was an outboard skiff with a windshield, not much longer than my sneakbox, with gear heaped all over the boat. The oars had scraps of plywood added to extend the blades, and the nails were bent over and hammered flat against the plywood. I pulled alongside and said, “They tell me only a fool would row down this river.” This didn’t evoke a smile, even from one fool to another. The boat was, somewhere under all the junk, aluminum, painted white and red. I pulled my oars in and grabbed the gunwale. “Where are you from?” I asked. “Seattle,” he said. I introduced myself and shook hands with James.

He was middle-aged and had lived in Woodinville, Washington, a half-hour drive from my hometown. He’d been married and had a welding business. “My wife went kapooey, my business went kapooey, and I went kapooey. I made a contract with God then.” He sold his truck to a man in Idaho, and made arrangements with the buyer to send payments to James as he traveled. James bought a bicycle (which was now lashed on the skiff’s foredeck) and pedaled east. A few weeks out he called the man in Idaho; there had been a forest fire in his area, and things looked pretty grim. James told him not to worry about the money he owed, James didn’t want it. The next time James talked to him, the man in Idaho said, “You won’t believe what happened.” “Oh, yes I will,” James replied, “I’ve been praying for you.” James told me, “The fire came up to that man’s property and went around it; his place was untouched in one of the biggest forest fires Idaho’s ever had.”

James had been traveling since September and looked haggard. His eyes were bloodshot and thickly wet. The Coast Guard in St. Louis had noticed him and asked to see his life jacket. “I don’t need one,” he told them, “I’ve got this,” and showed them his Bible. When they pressed him, James showed them the PFD he carried. “They wanted to stop me being dangerous to my own safety.”

On the gunwale was a square of rusty steel that used to be a paddlewheel that James turned by bicycle cranks and a chainring amidships, but he’d given up on that and had started rowing. Behind the windshield was a pile of orange sleeping bags set out to dry after the morning’s dew. He slept aboard the boat under a canopy that pulled back from the windshield. In the bottom of the boat was a matted coil of multicolored braided 1 1⁄2″ line too large to be of any use on a small boat; it appeared to me that he slept on it. Trailing from the stern at the end of a short line was a huge white plastic bottle, empty now, but James said it would hold 25 gallons of fresh water when he reached the Gulf. At first, he had been called to go to New Orleans, now it was to the Gulf of Mexico or the Bermuda Triangle: “I don’t know what I’ll find when I get there or if I’ll die on the way. It’s whatever the Lord wants.”

The current carried us into Smoke Bend and through a line of eddies that set us spinning like dancers. As the sun circled around our heads the bill of his baseball cap cast a shadow that licked across his face. James said he had talked to grizzly bears and a moose during 40 days in the wilderness. “You know how dangerous a moose is,” and he spread out his hands to indicate a huge rack of antlers. “He stuck his huge head in my tent smelling me. Animals aren’t afraid of me. People are.” James told me that he had studied under a Japanese samurai and after eight years of study he was able to defeat his master and to tell who was coming up behind him and what good or evil they intended.

In the midst of our conversation, we both looked upriver at the same instant. There was nothing on the river and there was only silence. Then I could hear a low thrumming. We both had spent enough time on the river to sense tows before we were aware of hearing them. Despite our obvious differences, the Mississippi had given us something in common that few people share. I wanted a picture of James and his fantastical boat, but I could not bring myself to put a camera between as. We shook hands and pushed off. “Remember me” was the last thing he said before turning his bow downstream. I was close to tears as I watched him fade into the distance over LUNA’s stern. We had traveled the same river, but it had brought me joy and James pain. I didn’t take my eyes off his boat until that last flash of his oars was erased from the horizon by the shimmering heat in the air.

At Donaldsonville, I was taken to the store and back by a man named Tal, who worked at a barge fleeting operation. He told me of the recent grounding of the stern-wheeler MISSISSIPPI QUEEN. Striking a barge, she had a 25′ hole torn in her hull but that wasn’t enough to sink her. The captain had run her onto a bar around the bend and she was taken off and down to New Orleans for repair.

I made camp on the downstream side of Point Houma with my tent set on a narrow perch above the river. At the door of the tent, I cooked my dinner, a two-can mix of beef stew and barbecued chicken. When it was hot, I brought the pot inside and zipped up. Before settling down to eat I smeared my company of mosquitoes against the walls. Only one had already had its fill of my blood and left a 2″-long black streak on the blue nylon wall.

Later in the evening, I heard a noise like an avalanche of empty oil drums. I unzipped the door and peeked out over the river. A few dozen yards away a ship was sliding downriver but all I could see was its superstructure, like an office building on the move. The ship was moving stern-first with three tugs rumbling at its port flank. There was little to see of the tanker, only the lights above the sheer. The hull was invisible, just a long hole in what had been an illuminated skyline. The tugs spun the tanker end for end in the middle of the river and then pinned it against a dock on the far shore. I crawled back into the tent, smeared a new batch of mosquitoes on the walls, and snuffed out the candles for the night.

At the town of New Sarpy, 25 miles upstream from New Orleans, there were several boats tethered to the banks, and the men aboard them were making long sweeps in the river with nets on hoops at the ends of long poles. When I pulled ashore next to one of the boats, the fisherman in it kept his rhythm while watching me come ashore. He had a full dark brown beard, and his hair was bound by a red bandanna. He was bringing up five or six quivering silver fish with almost every sweep. “Where you come from?” he asked. “Pittsburgh,” I said. He introduced himself as Tom and nodded to Joey, his 11-year-old cousin, who was seated by a fire of broken wooden crates. Tom had already filled five of the bentwood bushel baskets in his boat. When he asked if I’d seen a lot of dip nets upstream and I’d said I hadn’t, he was pleased. He would get a better price for the shad. When I headed out again on LUNA and drifted past Tom, still intent on his fishing, he asked, “Where you come from again? Pigsburg?”

Jane Cunningham

Jane CunninghamI arrived in New Orleans in the rain and was taken home, with LUNA, by my father’s cousin and his daughter.

In the last 20 miles to New Orleans, I wove in and out of anchored freighters from Hong Kong, Singapore, Bergen, and Tokyo, but most of them were from Monrovia. I arrived in New Orleans in the early afternoon of a bright New Year’s Day. I brought LUNA ashore for a break at the home of my father’s cousin, Joe, and his daughter Jane. They took me and LUNA home with them so I could rest up, spend some time with them, and see a bit of the town.

The Cunningham household in New Orleans made for a very pleasant stay for both me and LUNA.

Jane Cunningham

Jane CunninghamAfter my break with relatives in New Orleans, I resumed rowing in a drizzle.

Jane Cunningham

Jane CunninghamIn a goodbye salute to my New Orleans family, I stood up in LUNA , making my boat look even smaller.

It was raining when I set out again three days later. In less than a mile I had rowed from a drizzly overcast into a dense fog that blanketed the New Orleans waterfront. Rowing against the current to hold my ground ahead of a tethered barge, I peeked around it to see if the river was clear alongside of it. There was only fog. I let the river carry me into the ash-gray murk.

“You wanna die you just keep doin’ what you’re doin’,” came an amplified voice from a shadow above the decks of the barge. Suddenly I could see a tug bringing another barge in against the wharf. The tug’s skipper spoke again over the loudhailer. “Why don’t y’all set a spell until you can see where you’re goin’.”

I retreated upstream and threaded my way through the pilings to a debris-littered slope of sand between wharves. An hour later the fog appeared to have thinned, and I crept back out to the river. I drifted, listening to the noises around me. I slipped by the stern-wheeler DELTA QUEEN and along the gray-green flanks of a freighter. The intensity of the noise ahead increased. Above the fog I could see three lights on a vertical staff, the mark of a dredge. I pulled quickly against the current to keep from being drawn into the web of cables and pipelines that usually surrounded a dredge.

I called out to a crewman aboard a tug that was made fast to the pilings of a high wharf and asked if I could wait out the fog with them. I spent the rest of the day with him and his crewmates aboard SANDRA KAY watching TV and snacking in the galley.

After being squeezed between a tugboat and a row of pilings, LUNA survived with only a bent brace for the oarlock stanchion; it was easily straightened.

I felt the tug shudder, and one of the crewmen bolted out the door as the rest of us followed. A tug had come alongside SANDRA KAY and pushed her stern into the pilings, closing the gap where we had tied LUNA. The sneakbox was pinned and it took three of us to dislodge her. A brace for the starboard oarlock stanchion was bent, but there was no other structural damage. With LUNA secured across the tug’s stern, we returned to the galley.

After LUNA was nearly crushed between SANDRA KAY’s starboard side and the wharf pilings, the crew and I moved her to the tug’s stern.

The fog lifted at 11 that night and the navigation lights across the river streaked the full width of the black water with red, white, and green. After SANDRA KAY got a call to escort a tanker up from the Mississippi Delta, I cast off from the tug and paddled into the forest of steel pilings beneath the Canal Street Wharf. With loops of line from bow and stern, I tethered LUNA in a space between four pilings. I cleared a space in the cockpit and spread my pads and sleeping bag in the bottom of the boat. Though I had rowed fewer than 7 miles since morning, the day had left me in a condition to sleep through anything. I crawled into bed wearing my life jacket and fell asleep jostled by the syncopated rhythm of the waves beneath the wharf.

In downtown New Orleans, the pilings under the Canal Street Wharf made a refuge comfortable enough to get a good night’s sleep.

At dawn, amber sunlight slanted under the wharf and woke me. After I had stowed my bedding and gathered the four mooring lines, I slipped out from the thicket of pilings to the river. Drifting with the current past the three tall black-slate-shingled spires of the St. Louis Cathedral opposite Jackson Square, I set the oars in the locks and pulled the last mile to a canal that would take me beyond the banks of the Mississippi River and out into the wide waters of the Gulf of Mexico.![]()

Part one of this series in the January 2023 issue of Small Boats.

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats. Some of the passages here were taken from stories I wrote for Nor’westing and Small Boat Journal in the late 1980s.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Readers of this adventure might enjoy Life on the Mississippi by Rinker Buck: flatboat build, flatboat history, and the trials of flatboating today. An outstanding read.

Funny how when one spends big bucks on a boat with a berth, one then needs to spend even more on marinas, and/or motels. But when one says “Ok I can travels 1000s of miles on something I built in my backyard, I can travel nearly for free.”

Has to do with the Law of Conservation of Mass. The bigger a thing is, the more it takes to maintain. I learned to live this out when I went without a house or car for three years, worked an average of one day of labor a week, and ate in restaurants nearly every day.

Very expansive feeling, isn’t it Chris, when you know the only things you need to support are within an arm’s reach of yourself?

After reading this, I wanted to meet and talk more with Johnson, and hoped that James found some joy along his path . I had so many questions throughout your engaging and brilliantly written essay, Chris. One that I have, is “What motivated you to set out alone in the winter, knowing there would be so many challenges?” This adventure seems much more risky than biking to the Grand Canyon in August!

I would love this to be turned into a novel as I am drawn to the human-interest part of all of this.

The book about the cruise of the Jack de Crow from central England to the Black Sea is a great rowing adventure story albeit the rower was a professor of Old English Literature and so probably imagined some of it.

Where’s the complete article?

And the build process?

Here are links to the second and third parts of the story:

A Sneakbox on the Mississippi

A Sneakbox on the Gulf Coast

For a glimpse at the construction of the boat:

Driftwood and Windfalls