On December 2, 1875, Nathaniel Holmes Bishop launched his sneakbox, CENTENNIAL REPUBLIC, on the Monongahela River and rowed along the south shore of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, into the headwaters of the Ohio River. On November 9, 1985, I launched my sneakbox, LUNA, on the Allegheny River and rowed along Pittsburgh’s north shore to the confluence with the Monongahela, that same Mile 0 of the Ohio. Bishop spent the next four months traveling 2,600 miles to reach Cedar Key on Florida’s Gulf Coast. I’d follow the route he detailed in his book, Four Months in a Sneak Box.

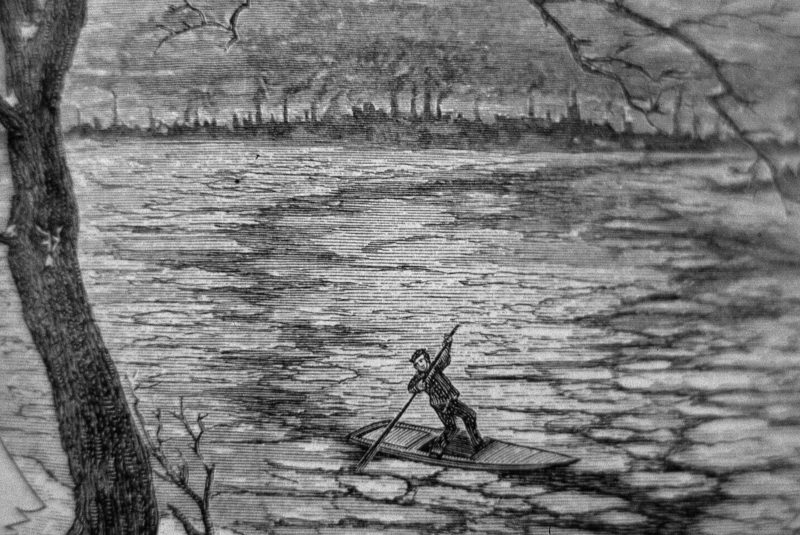

from "Four Months in a Sneak Box" by Nathaniel Holmes Bishop, 1879

from "Four Months in a Sneak Box" by Nathaniel Holmes Bishop, 1879This illustration from Four Months in a Sneak Box convinced me to get on the Ohio River a month earlier in the year than Nathaniel Bishop had so I could avoid getting blocked by ice.

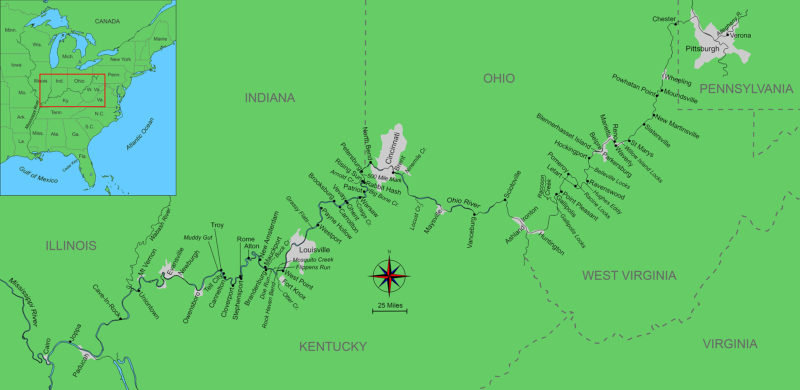

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorOn November 9, 1985, I entered the Ohio River at the confluence of the Allegheny River, flowing under the bridges at left, and the Monongahela, merging from the right at Pittsburgh Point. On December 2, 1875, Nathaniel Bishop had been blocked at this spot by ice that had flowed from the Allegheny.

Six miles downstream from the confluence, I arrived at the first of the Ohio River’s 20 dams and locks, but I had to head ashore so I could walk up to the lock office to get someone’s attention. The entrance to the lock was jammed with debris. I had no radio—handheld VHFs weren’t practical for small boats then—the recreational boating season was long over, and my 13-1⁄2′ boat easily escaped notice.

When I pulled the boat up on the mud, which was more a greasy ooze than wet dirt, I lost my footing and struck the bow with my shin. The cold-molded hull resonated with a sound like a splitting maul hitting a wedge with its handle. A pink bruise swelled up in seconds and looked like an extra kneecap.

In Verona, on the day before I launched, I spread all of my gear out on the floor of the Sylvan Canoe Club’s meeting room. Neatly packed, it would all fit in the sneakbox without having to carry any excess gear on deck.

I got through the first lock, and then the second one 7 miles downstream, before pulling ashore at a riverside park. I set myself up for the night in a picnic shelter with a table for my bed. Driving 2,500 miles from the Seattle area to Pittsburgh, a distance equal to the cruise that I had ahead of me, and getting equipped to launch from the Sylvan Canoe Club in Verona had worn me out. After the first day’s 27 miles of rowing, I was exhausted. Not long after I crawled into my sleeping bag, a heavy rain slanted into the shelter on a stiff breeze. I lay there cold and utterly dispirited until exhaustion turned to sleep.

This new adventure was my second following in Bishop’s wake. In 1983, inspired by his book, Voyage of the Paper Canoe, I’d paddled a paper cruising canoe I’d made from Québec to Cedar Key, a distance of about 2,500 miles that took four months to cover. I had travelled with a partner then, but for the sneakbox voyage I was eager to go it alone. Doing the trip in the winter, as Bishop did, would be a better test of my skills and endurance. I just hadn’t expected to be put to the test on the first night.

I had built my sneakbox, LUNA, to plans in Howard Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft. The original boat had been built in 1880 and was described as “an old professional gunner’s sneakbox of a superior model.” It was 12′ 2/3″ long with a beam of 44″. Bishop’s sneakbox, CENTENNIAL REPUBLIC was 12′ long, 46″ in beam, and weighed 200 lbs. I wanted a longer, lighter boat and stretched Chapelle’s sneakbox to 13′ 6″ and cold-molded it with western red cedar. Bishop’s daggerboard trunk was centered and forward of the cockpit; the Chapelle design has it set to starboard just outside the cockpit coaming. The offset board had no effect on sailing performance and made the space under the foredeck more easily accessed.

I couldn’t bring myself to get up at first light though I had been awake in the dark of early morning. I loaded the boat and set out without eating breakfast. As soon as I was on the water it started raining lightly, covering the river with interlocking concentric rings like chain mail. There were a lot of factories lining the river, but only a few had lights on. On the left bank, two nuclear power plants with five 500′-tall concrete cooling towers billowed sugar-white clouds of steam.

I was soon out of Pennsylvania and in between Ohio and West Virginia looking for a place to go ashore. In Chester, I rowed up to the East Liverpool Yacht Club and set the nose of the sneakbox on the launch ramp. As I walked into town, I passed a couple who looked at me with the intensity of residents checking out a stranger in the neighborhood. After I found a pay phone to call home, I passed the same couple on my way back to the boat, and the man asked, “When’s the last time you had pizza, Chris?” George and Gladys had seen the article about my voyage in The Pittsburgh Press, had recognized my boat on the ramp, and had just left a bag of food for me there. They offered me the use of the East Liverpool Yacht Club for the night. It was near 4 p.m. and sunset was just an hour away, so I took them up on it. They helped haul my stuff into the clubhouse and after they left, I ate the ham sandwich, fried chicken, corn chips, and Cheetos they’d given me.

The following day, I covered 46 miles, a remarkable distance considering I averaged 25 miles per day on the Inside Passage where I didn’t have the advantage of a steady current in my favor. I stopped at Wheeling, West Virginia, and hauled LUNA out on a broad park lawn on Wheeling Island. I spent the night in the boat and woke to lightning and thunder at 3:30 in the morning. Soon the rain was hammering on the hatch cover with the sound of lead shot spilled down a staircase. I tried to sleep, but the lightning flashing tail light red through my eyelids and the crack and rumble of thunder kept me awake.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

At 6 a.m. I started getting dressed, in the boat, a particularly painful process. To slip into my pants I had to lift myself by pressing my spine onto the edge of the cockpit coaming thereby lifting my hips. Getting my shirt and rain shell on was not too difficult, but once I had slipped into my life jacket, it took another three or four minutes just to get into my slicker. Getting fully dressed took almost half an hour.

I never saw any other recreational boats in the 28 days I was on the Ohio and barge traffic was light, so light that I always had lock chambers to myself. At the entrance to some of the locks there were pull chains that small boats could use to signal the lock keepers of their arrival. However, most had been disabled. Thus, if a lock keeper didn’t happen to catch a glimpse of me, which was usually the case in the fog, I’d have to land on the riverbank upstream, secure LUNA, and walk up to the lock keeper’s station. They were often surprised to see me arrive on foot, but always quick to open the gates. There were two locks at every dam, both 110′ wide. The smaller locks are 600′ long and the larger are 1,200′, which accommodates a tow with up to 15 barges.

The river had risen 1′ or so overnight and the sneakbox was nearly afloat. The daylight seeping through the fog was beginning to fill in the dark around the lights of the city. I passed under two bridges in Wheeling as a hard rain began to fall; crystalline stalks of water rebounded with each rain drop catching the morning light while the river glowed a fluorescent white.

Downriver I stopped at Powhatan Point to buy postage stamps. There was a pumpkin floating downstream as I pulled up Captina Creek along the edge of town. High water had pushed the banks of the creek up into the lawn of the park that bordered upon it. I rowed into a small pool cupped between two hills on the rolling lawn and tied the painter to the trunk of a mop-headed willow. I idled in town by shopping for food and buying stamps and post cards.

A mile from the point I caught up with the pumpkin, spinning idly in a back eddy behind a line of riprap sticking out from the right bank. As the river level continued to rise over the first two weeks of my month on the Ohio, the type of river trash changed. At first there was driftwood swept from riverbanks, then yards and playfields were stripped of basketballs, tennis balls, baseballs, a set of football shoulder pads, and an aluminum baseball bat which floated upright like a spar buoy. It would not be long before the turbid water breached porches and pilfered coolers, toys, and furniture.

Tired and hungry after rowing upwind for a long straight stretch of the river, I looped the painter around a large driftwood branch and let it tow me upwind as it drifted downstream.

There had not been much traffic on the river and by the time I reached the Hannibal Locks at mile 124, the gates hadn’t been opened for a while to let tows and debris pass through. I worked past stumps with their roots fanned out over the water, empty wooden cable spools, felt-tip pens, light bulbs, and plastic spoons. The small pink hand of a doll reached up through a dark brown patch of crumbled tree bark. One of the lock keepers had been watching me from high up on the lock wall. “Seen any West Virginians out there?” he asked. “I heard on the news that 53 of them got swept away and may be coming downriver. Keep an eye out for ‘em.”

When too much debris accumulated at a lock entrance, the lock keepers would open the upstream and downstream gates at the same time and let the river flow unimpeded through the chamber. After the logjam broke up and passed through, the gates were closed again.

The flooding was not uncommon for this time of year. Bishop wrote: “The water had risen two feet and a half in ten hours, and the broad river was in places covered from shore to shore with drift stuff; which made my course a devious one, and the little duck-boat had many a narrow escape in my attempts to avoid the floating mass.”

At the entrance to this lock, a logjam prevented me from rowing into the chamber. I tied the tail end of my 33′-long heaving line to my painter, swung the golf-ball-weighted monkey’s fist around my head and let fly. The two lock keepers could then drag me across the debris into the lock chamber.

The signal light changed green but I was stuck in a tightly packed raft of wood 20 yards from the opened lock doors. “Can I throw you a line?” I called up to the two lock keepers now watching me. They nodded. I tied the painter into the tail of my 33′ heaving line and slung the monkey’s fist up at the wall side. The rope-wrapped golf ball zipped by the head of one of the lock tenders at eye level and draped the line over the shoulders of the other. The one who wound up with an armful of line smiled at the accuracy of my throw, the other was wide-eyed at nearly being cold-cocked. They hauled away along the wall of the lock and LUNA skidded up over the drift and into the lock while I kept her away from the rough concrete walls with the butt of an oar. From the downriver end of the lock I rowed a quick mile to New Martinsville and spent the night at the Magnolia Yacht Club.

I was in no hurry to be on the water at first light the next morning. It had been a rainy night and at 3 a.m. I’d had to get out of my warm bed, and pull on my cold, wet boots and pants to check the boat. The river was up another foot, so I jockeyed the boat up the mud enough to give me the rest of the morning to sleep.

At midday I stopped at Sistersville, a town with two boat ramps on the river. I hauled out in the middle of the upstream ramp that looked less like a ferry dock. I bought some post cards at an old soda fountain in town. The ceiling was high and its lighting dim. The proprietor, a man in his 70s, was smoking a cigar. Two men, his contemporaries and, I suspect, his loyal customers, were seated on pedestal stools talking quietly but looking at me. I still had my life jacket on over my bright yellow slicker and under my bib front rain pants, looking not a far cry from a circus act.

I walked to the city hall to take advantage of the restrooms and on my way back to the boat, I stopped in at the office of The Tyler Star-News, the town newspaper, to offer them my story. A little press had always been helpful on my long cruises. The editor called in a young cub reporter and the two of us stood squared off to one side of the editor’s desk.

He asked me why I was making this trip. I answered: “A man named Bishop traveled this same route in 1875.” It had the sound of an answer and people often accepted it as one, but I really expected someone to say, “So what?” I suppose a more honest answer would be that I like finding solutions to problems, but I didn’t set out from Pittsburgh looking for trouble.

“Well,” said the cub, “I guess it wouldn’t hurt if we took some pictures.” We drove down to the ramp and after posing for two photos I rolled the boat down the ramp on my collection of boat fenders and pushed out into the current. While newspaper articles had been helpful during my paper-canoe adventure—we were often warmly received by readers who saw us paddling by—I was traveling twice as fast with the current’s help beyond a newspaper’s reach by the time an article would come out. I stopped dropping by newspaper offices.

Bishop writes of the origin of the sneakbox: “Captain Hazelton Seaman, of West Creek village, New Jersey, a boat-builder and an expert shooter of wild-fowl, about the year 1836, conceived the idea of constructing a boat for his own use a low-decked boat in which, when its deck was covered with sedge, he could secrete himself from wild-fowl while gunning. Seaman named the result of his first effort the Devil’s Coffin.” The sleeping accommodations aboard LUNA were snug for a living being. Without lilies for my open-casket tableau, I had to settle for bananas.

I stopped for the day in the woods on the left bank just upstream from the town of St. Mary’s and took a sponge bath that evening. Lacking a sponge (except the one to soak up bilge water), I used a bandana to both wash and partially dry myself. The rest of my drying I did in my clothes. I didn’t wash my hair. No matter how it may have looked, it felt pretty good after being rinsed incidentally almost daily by rainwater.

The mud on the river banks was deep, as thick as shortening, and as slippery as grease. The two dark-blue shapes at the lower left are my socks. The mud had created so much suction that it pulled my boots and socks off when I got stuck and I couldn’t move except by stepping out with bare feet.

My clothes needed washing, especially my wool pants, and the pair of socks I had worn continuously for five days and four nights. Mud got on everything I wore and everything in the boat. It had even climbed from my boots up the inside of the legs of my rain pants. After I crossed a muddy ditch to get to a supermarket on the Kentucky side of the river, I had wiped my boots thoroughly on the mat at the entrance, but the pant legs sprinkled muddy outlines of my boot heels on the floor. Only when I got to the checkout counter did I see that I had left a path on every aisle I’d walked.

Shortly after noon, I left St. Mary’s under thinning clouds through which I could see a well-filtered outline of the sun. I took advantage of the warm breeze to air out my boots and socks. Though I was rowing into the wind, the odors of whatever I stowed on the afterdeck or in the cockpit circulated up to my face. The smell of my bare feet, socks, and boots were like the breath of an old dog in poor health. It only went away when I put my socks and boots back on.

At the Willow Island Locks, the lock keeper shouted at me to tie up on the bollard, the one recessed in a slot in the lock wall that floated down with the water. I was sitting in the middle, away from the walls, where I preferred to be. I threw a line up over the bollard and held it in one hand while I made a sandwich with the other. The day went well, 37 miles, a short distance, as I got off the water early in Waverly at 4 p.m.

I hadn’t brought a spoon and it wasn’t pleasant eating Grape-Nuts with milk, a favorite breakfast, without one. Necessity drove me to make a spoon out of one of my film canisters.

As at most of the places along the river, the docks had been hauled up on the bank for winter, but I found a ramp and a park picnic shelter with a roof, a table, and a chair. I badly wanted Grape-Nuts for dinner. Two days earlier, I had bought a box and was looking forward to having that crunchy cereal for breakfast, but I hadn’t packed a spoon. I’d been improvising with a sail batten but while that worked for rice pilaf, it let all the milk run out of the Grape-Nuts. I tried to slide the cereal from the cup with a ball-point pen, and then with my fingers, but fared no better. That had been getting my days off to a bad start and when I got to Waverly, I was on the verge of knocking on doors to beg for a spoon. On the picnic table where I’d scattered my gear, I had an empty Kodak film canister. I went to work with my pocketknife, turned it into a spoon, and that evening finally had my Grape-Nuts with milk in every mouthful. That small pleasure had an outsized impact on my frame of mind.

I started the trip rowing with the ends of my fingers, the way I usually row, but after a while my fingertips were sore and blistered. I shifted to the middles of my fingers until they wore out and then moved on to my palms. They each developed hot spots, but my fingertips were then ready to use again.

During this break-in period, I took hold of the oar handles with the same care that a shot-putter uses to settle the shot in hand, twiddling my fingers to sit on the oar squarely so that there was only compression pressing the layers of skin together, not the shear that would pull them apart. After a few strokes the stinging went away, and I could pull. The blisters I got started out white, especially when the skin was wet, and with time turned a bit yellow, then brown when the separated layers of skin fused back together.

I was on the water at 7 a.m. from Waverly and it started raining five minutes later. Heading toward Reno, I ran into a thick fog being swept upriver by the wind. There was not much to see in Reno, except a sign saying “George Washington Slept Here,” and all I saw of Marietta from the river was a McDonald’s sign rising over a mound of tires heaped on the bank.

I bought a spoon in Belpre and then rowed across the river to Parkersburg, an uninviting city walled in against the floodwaters, where I met Harry, who was working on a sternwheeler he had been building for seven years. He gave me a ride to the post office and back so I could collect letters sent to me via general delivery.

The Ohio took a sharp turn around Belpre from south to west and then divided on either side of 3-1/3-mile-long Blennerhassett Island. The river arced south again around a mile-long bend crowded with factories that made the air smell like plastic. A southerly was making a steep chop on the next gentle curves of the river and I kept close to the shore where there was less wind.

I pulled into Hockingport, walked to the general store—the only store in town—and picked up some cookies, bread, and canned soup. In the next few miles downstream, I ate the whole package of the cookies.

The box I used as a seat in the sneakbox also served as a seat ashore. It had a watertight door for access to the frequently used gear that I kept inside it. I knew from previous long cruises that my memories didn’t always paint a complete and accurate picture of the experience, so I made a point of taking pictures of myself on days when I was feeling worn out.

At the Belleville locks, no one responded to the recreational-craft buzzer, and once again I had to tie up the sneakbox and walk to the operations building where I met lock keepers Tom, Bob, and Aaron. Tom and Bob showed me around the lock control system, which bristled with a lot of lights, dials, and buttons. They gave me access to a shower and after I toweled the steam off the mirror over the bathroom sink I was surprised by how terrible I looked. My eyes were bloodshot, unshaven I looked like a fugitive, and my neck was chafed cherry red by the collar of my raincoat, getting scraped every time I turned my head to see where I was going.

Tom offered to put me up for the night, so I secured the boat up away from the water on a small beach strewn with rock and wood debris. I was tired and thought I had put in a full day of rowing, but it was only 2 p.m.. We drove to the 75′ mobile home where he introduced me to his wife, Regina. Their schedule wasn’t governed by nightfall, and it was near midnight before I got to bed. I heard the furnace come on twice during the night and all the heat made me sweat and gave me nightmares.

In the morning Tom woke me at 7, gave me a bowl of cereal, showed me his motorcycles—all 20 of them–and took me back to my boat. He stayed to watch me row off. Having someone to say goodbye to made it a better morning than most.

The wind had shifted north and brought the cold. With a long stretch of south-flowing river, I considered sailing all morning and looked for places to put in and get the sailing gear out of the boat.

During a break of blue sky, sunshine, and warm air, I took my socks and boots off to air out my feet. The soles of my feet and my toes were black with sloughed-off rubber. I pulled into Ravenswood to find new boots. I bought new socks and boots, 1-1/2″ taller, clean, and sweet smelling.

The high water flooded the mouth of Sandy Creek where it flowed into the swirling Ohio River. A railroad bridge made of timbers black with creosote spanned the tributary. I set my camera and tripod up midspan, returned to the boat and triggered the camera with a radio-controlled remote.

I rowed to the downstream end of town and pulled LUNA up on a lawn alongside the railroad bridge that crossed Sandy Creek. Before heading back out on the river I set the camera on the bridge to snap a picture of myself rowing out to the Ohio.

Since this was already turning out to be a short day, I took the time to extract the mast, sprit, boom, centerboard, and rudder. Before the sails were even up, they were spotted with mud and black grease from the oars. There was barely enough wind to push me out of the creek into the Ohio but a bit of a breeze came up as I headed toward an upriver tow. I inched to windward as it went by then fell off to sail through its wake.

I’d put an access port in the transom that allowed me to carry LUNA’s mast, sprit, and boom below decks. The spars were out of the way there but setting the rig up took a long time. I sailed a few times but bends in the river made it impractical and the spars would spend most of their time stowed until I got to the Gulf of Mexico.

Two miles downriver I gave up on sailing and dropped the sail, sprit, and boom before rowing to a stretch of the riverbank called Hughes Eddy. The still-standing mast was flailed by a few branches before the hull hit the mud. I swung one leg out and sank in mud to within an inch of the top of the boot. I shifted my weight back in the boat and had to curl my toes upward to help release the boot out of the mud. I rowed downstream and found a dirt ramp where the mud was only 10″ deep. Every step I took was still a struggle and as greasy mud spread everywhere I struggled to keep my frustration and anger in check.

Afloat again, I wiped the mud from the decks, boots, and cockpit as LUNA drifted. As the boat came back into shape, I recomposed myself. I rowed hard enough to burn up some energy, but not so hard that I would tear up my hands. At Letart, the river turned north, into the wind, and I pulled a slow 2 miles into the Racine locks.

There wasn’t any turbulence when locking downstream, so I took advantage of my time in the chamber by having a bite to eat. I braced my feet against the floating bollard and held LUNA in place with a loop of red line connecting an oar, tucked under my legs, to the bollard. The usual fare was a cheese sandwich with mustard and sliced tomatoes or cucumber. The wool pant legs that served as my kitchen counter couldn’t be sponged clean so they stayed speckled with dried tomato seeds and mustard.

I locked down with a loop of line around the floating bollard and an oar under my legs, leaving both hands free for sandwich making. The light was fading as I got out of the locks, so I looked for a place to get off the water. I found a small dirt ramp near two empty houses and a house trailer with a broken window. I set up my blue tarp on one of the porches and put my sleeping bag and pad under it. Cold and tired, I was eager to sleep and put the day behind me.

During the night a bright light flashed repeatedly on the tarp. I worried that it might be someone wondering what I was doing on private property, but realized tows were sweeping spotlights across the river looking for the reflective channel markers.

As usual, it had rained in the middle of the night and again as I was loading the boat. A week of rowing had loosened the bronze oarlocks. I had lubricated them with Vaseline, but rain washed it out. The only two moving parts in the boat were slowly turning each other into a black paste of powdered bronze. Hearing the locks knocking all day long quickly got annoying. I made stops at Pomeroy, a one-street town squeezed between the river and a row of 250′ hills, and at Point Pleasant, a walled-in town with room to spread upstream from the Ohio’s confluence with the Kanawha River, but had no luck finding grease for the locks.

It started raining again as I passed under the bridge at Point Pleasant. I was to the point that I tried to ignore it and didn’t put my slicker on. Maybe it would stop. I sang a lot during the day to keep myself company. I didn’t know all the verses to “Poor Wandering One” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance, but there was no one to complain about my singing what I did know over and over.

Most of the boats in marinas were hauled out for the winter and empty covered slips were great places to spend the night. I took advantage of a laundromat near this marina to wash my clothes.

I rowed along the Gallipolis riverfront and up Chickamauga Creek to the Gallipolis Boat Club and stopped for the day around 3. All but five boats had been hauled for the winter and even the covered slips were empty. I coasted into one with a shag-carpeted floor. The door was locked by a hasp on the outside, but I managed to lift the nail out of the hasp with a piece of electrical wire. I walked into town and did the laundry and some shopping. It felt good to get into clean clothes; I’d been wearing the same things for a week. Back at the slip I cooked leek soup with rice and walnuts, pulled wet gear out of the boat to dry, and sponged the cockpit clean.

Some heavy downpours had rattled the corrugated metal roofing soon after I settled in after my walk into town, making me especially glad to be clean, warm, and dry, but at dusk the sky cleared to reveal a bright crescent moon—even its dark side was visible—and its sharp upper cusp pointed at a bright pinpoint of yellow light, Jupiter or Saturn. The only things this camp lacked were running hot water and company. My recent conversations had been incidental and short.

My hands had become callused enough to make rowing comfortable, and my feet had stayed dry in the new boots, but I needed a break in the weather and a chance to visit some people to renew my energy. The rain made everything harder, washed the scenery to a dull monotonous gray, and kept people indoors.

It was a cold night. The chilly wet air settled over the creek and seeped into my sleeping bag. I lit the stove and heated up a pot of water to pour into my screw-top water bottle, slipped it into a sock, and pushed it to the bottom of the sleeping bag. I pressed my feet around it but its warmth only made the rest of me feel colder.

At dawn, I rowed out of Chickamauga in a thick fog. An upriver breeze poured its cold around the back of my neck and seeped into the gap left by a short-tailed shirt. I couldn’t row hard enough to generate any heat and the faster LUNA moved, the colder the air felt. I took one of my pogies (gloves made to fit over hands and oar handles) off one hand and tucked it under my hat to hang like the tails on a French Legionnaire’s cap then tucked a spare sock in my collar.

In the trees there were several great blue herons, balanced improbably on legs as slender as pool cues. Smaller birds perched nearby with their feet clenched like burls around the branches. The mist made the air heavy, and I could feel its resistance as if I were snowshoeing in powder snow. Visibility was poor; I listened for the hiss of lead barges in tows and the sound of water tearing at snags projecting from the bank. I slipped by Racoon Creek where the muddy Ohio swirled its silted water in the creek’s translucent green pool like cream stirred into coffee.

I rowed into a new chart and discovered I was just 2 miles upriver from the Gallipolis dam and on the wrong side to enter its lock. I crossed over, listening to the sounds sifting through the thick fog. There was the rumble of a tow’s distant engine. I turned my head from side to side to silence the wind’s whisper in my ears. The rumble of a tug’s diesel engines comes from the rear of a tow and the bows of the lead barge can be more than 550′ from the engine noise. Beneath a lead barge’s long overhang there is only a quiet hiss of water being pushed under. That’s what I was listening for.

I had been warned about staying too close to the banks here when a big tow comes through. If barges are locked through it in two sections, the tow will push the first section into the bank and leave it parked there. I saw chains with links as big as footballs and hooks for barge hawsers, but I slipped by without having to evade any barges.

The industrial area around Huntington and Ashland thinned out as I went down river. The limbs of flooded trees combed plastic bottles and jugs from the water. The hills eased back from the river, leaving wide bottoms beyond the banks. As it grew quieter, I heard what I thought might be the air mattress squeezing out air or the stove leaking fuel. I crawled into the cockpit headfirst to find the source of the sound and realized the hiss was the sound of the current sweeping gravel along the river bottom resonating in the hull.

I spent the night in a marina in Ironton, where I was given permission to sleep on the docks. I met Carl, who had been hanging out in his boat. He borrowed my cookpot to boil up a couple of steaks in plastic bags and when he returned the pot, he brought me a beef stew meal in a bag. On his way home he brought me an electric blanket and two extension cords. I plugged into the shore power and tucked the blanket into my sleeping bag. It was heavenly.

When the sun came out and the air temperature was pleasantly warm, I was eager to get out of clothes that I had been wearing day and night. During one long cold spell I slept in the same clothes I wore during the day for more than a week. My pants got so sticky that I had to pull them away from my legs in order to sit down.

The morning sky cleared, and the south wind brought warm air. After a stop in Sciotoville, I spread all my clothes on the afterdeck to dry and rowed undressed to dry my skin a bit. Four miles downriver, I passed by Portsmouth at what I thought was a discreet distance, but I think I unsettled an old couple out for a stroll along the river. If they had been naked that certainly would have been evident to me, so they must have seen that I was. I waved. They didn’t wave back.

The floodwaters gave me access to places that would be high and dry at normal water levels. I didn’t press far into this cornfield, but it looked like I could have rowed a mile or more before reaching high ground.

Coming up on the Scioto River at the west end of town I had to keep tight to the Ohio’s bank to allow room for a huge tow to pass. The Scioto runs through a wide valley where the hills on the Ohio side are set well back from the river. A flooded cornfield stretched almost two miles from the river to the hills. I rowed into it and set the boat among the stalks for the coziness of it.

For several chart pages there were no towns marked, only river navigation lights, day markers, and creeks. Tangled gossamer threads drifted across the river. A butterfly flew by over the stern. It could have been summer, but there were no leaves on the trees and the ash-colored contours of the ridges of the landscape were clearly visible under the latticework of trunks and branches. By the afternoon the warm air was rippling the horizon.

I stopped for the night at the riverfront home of the Bowden family. Timmy, 10, gave me permission to spend the night in his treehouse.

Fifty miles of rowing from Ironton put me in Vanceburg. I got dressed for landing. Tucked in a dent in the shoreline where the water spun debris in an eddy, a lawn sloped into the water. Fifteen feet from the water’s edge was a treehouse. I landed and asked at the house farther up the bank if I could pull off the river for the night. A Mrs. Bowden said that would be fine. Her son Timmy trotted to the door to have a look at me. “Is this the man in charge of the tree house?” I asked him. “Would it be all right if I camped in it tonight?” Timmy was beaming with the honor of hosting a stranger.

As I was tossing gear up into the house, a 6′ by 5′ platform, with one wall, a roof, and a roll-down shade, 10-year-old Timmy came down with hot chili, a can of Sprite, a cup with ice, and crackers wrapped in tin-foil. I’d done 159 miles in the past three days, without making myself miserable. The weather had been good, the river fast, and I’d been happy to spend whole days on the water. Things were looking up.

At 6:45 a.m. the next morning, Timmy walked me to a café to buy me breakfast. He ordered biscuit and sausage for $1. I ordered three pancakes, hash browns, and orange juice. His dad joined us and after breakfast the two of them saw me off. I pulled through the half-submerged leafless brush, through the back eddy, and into the driftwood-crowded Ohio.

The day was remarkably warm. Even the cheese was sweating. After 55 miles of rowing, I stopped at Big Locust Creek. Along the banks were two small docks in front of trailer homes all locked up for winter. I set up to sleep on the porch attached to one of the trailers. On its door was a sticker: “The owner of this property is armed. There is nothing inside worth risking your life for.” I took a chance on sleeping with his porch roof over me. I wouldn’t be inside, and it was going to rain again.

The accommodations at Ninemile Creek were meager and it was just as cold inside as outside.

I had a short day’s row, just 22 miles to Ninemile Creek where I found an abandoned shanty that had so many gaps in its walls of weathered boards that it was little better than sleeping out on open ground. The temperature dropped to about 25 degrees, and while I slept well enough, getting up was painful. My whole body ached with cold and my hands stung. The river had dropped about 3′ overnight; to get afloat I had to drag my boat down the bank past signs that said Danger, No Fishing, No Swimming, Sewer Effluent.

I was on the water by 7:30 and rowed hard to warm up. As the sun rose behind a bank of high clouds there was a thin vapor on the water. The breeze spun columns of mist 10′ tall and carried them like undulating towers of dishes across the river.

I ferried across to Brent where Harlan and Anna Hubbard built the shantyboat made famous by his book, Shantyboat. I put ashore at a ramp leading through a tunnel under a single railroad line. There were two old houses there; one had a light on. I rang the bell and an elderly lady came to the door. She remembered the Hubbards and said they were living downriver in some hollow. As I walked back to the boat, I remembered Payne Hollow and found on the chart two creek valleys where they might be. The Hubbards were two days away.

Cincinnati, surrounded by bridges, was striking in the morning sun, but no place for a small boat. Fourteen miles downriver at North Bend, I was headed south with a good breeze behind me. I deliberated over taking the time to get the spars out but put the mainsail up near Petersburgh and sailed to the next chart where the river takes a 90-degree turn. I ran about 3 miles making 8 mph over the bottom. I crossed the 500-mile mark and at dusk arrived at Rising Sun. I was again tired to the point where I would stand for long spells trying to remember what I was supposed to be doing. After I bedded down I slept well.

In the morning the light coming through the clouds turned water and land gunmetal blue. About 9 a.m., I pulled into Patriot and picked up some food in a well-stocked general store where the shelving leaned toward me as I walked by on the creaking wooden floor.

I hammered away at the headwind through the middle of the day. My right hand was sore, and the middle finger numb. The ramp at Warsaw was blocked by logs and I finally got off at Craig’s Creek. There I met Dan and his wife, Marsha. They knew of Harlan Hubbard and called up a friend, Carl, an Ohio River historian. Carl told me where I’d find Payne Hollow.

The next lock was just 1-1⁄4 miles downstream. I pushed on past Vevay and Ghent, stopped for food and water in Carrollton, and arrived at Brooksburg at sunset under a wash of color in the sky that ranged from peach at the horizon to lavender above. The gibbous moon spattered on the water with mercurial reflections. I rowed by moonlight to Indian Kentuck Creek where I found a float with an aluminum skiff resting upside down on it. I shoved the skiff to one side and suspended my tarp over it and my tripod.

My feet were cold as I cooked dinner and never warmed up. When I slipped into my sleeping bag, I couldn’t sleep. At midnight I put on more clothes and put my pogies on over my feet. If I stayed motionless, I could keep a veneer of warmth around me, but I still couldn’t sleep. I waited for sunrise.

I had never spent a night so cold as the one I spent on this raft. My sleeping bag had a silvery coating on the inside to reflect heat, but it had worn off after a week and turned itself into a summer-rated bag. I slept in my clothes, but that did little to fend off the cold that settled into this inlet just a few dozen yards from the river. As the frost settled during the night I didn’t sleep at all. I just waited for first light so I could break camp and start rowing to warm up.

In the morning, everything was white with a bristling fur of frost. It took 15 minutes to get up the nerve to unzip the sleeping bag and let my envelope of lukewarm air drift away. As I got dressed, the tarp dropped mica-like flakes of ice on me. To keep my gloves from getting wet I stuffed the tarp into its sack bare-handed. My fingers quickly turned stiff and red. I was under way by 8 a.m. and by 9, the morning sun was dimmed by a zinc-gray membrane of high haze. In the muted light I rowed past a Kentucky shore that had a metallic gleam of frost as if the entire landscape had been electroplated in silver.

Payne Hollow was just 17 miles downriver. When I arrived, the only thing marking the place was an aluminum johnboat pulled up on the sand in a thicket of leafless saplings. As I rowed ashore, LUNA grated over a rock and I knew from the sound that there would be some damage. I pulled ashore, lifted the gunwale to check the hull, and found a deep gouge that had torn through the fiberglass and into the red cedar planking.

I found Harlan and Anna at home and introduced myself. They were both in their 80s, white-haired and soft-spoken. They invited me in. There was a grand piano in the living room and objects that they had made were everywhere. A kerosene lantern had as its chimney a Mason jar with its bottom removed and its lampshade was made from paper and baling wire. Resting on the pole rafters overhead was a popcorn popper made from wire door screen and a can that once held ham.

With all of my gear in the Hubbard’s johnboat, I could work on LUNA and repair the damage a submerged rock had caused when I came ashore.

I mentioned that I had damaged my boat as I arrived and asked if I could repair the boat, camp overnight, and leave the next morning. They insisted I stay as their guest and Harlan showed me the room where I’d sleep. It had a sink in a drawer that slid out like a flour bin with a drain to send the wastewater through pipes to the garden. The doors were hung at an angle so they would swing close. Harlan explained that the furnace in the cellar pumped heat up through a grating in the floor and circulated hot water in a convection system that “warms the cold corners of the house” with two air-conditioner tube-and-vane radiators.

In the afternoon, I emptied the sneakbox, set it on edge, and put a fiberglass-and-epoxy patch over the damaged area. That evening, after dinner with Harlan and Anna, I washed up in my room. The kerosene lanterns in the living room went out one by one. I heard the two of them saying goodnight to each other and the house fell quiet. It had been a long time since I’d slept in a bed, and to be doing so under the Hubbards’ roof was something I never could have dreamed of.

After an early breakfast, I began packing while it was still dark. Harlan came down to the shore to see me off and, with one last shove, LUNA slid down the mud as I crawled on her foredeck. The trees were bare: their leaves had fallen and blanketed the hillside with the color and texture of rust. White sycamore trunks at the water’s edge stood out against the dark-barked maple and locust. As tows appeared, pilothouses, barges, and wakes serrated the Ohio River horizon.

Sunday in Westport was quiet. Two men and a boy in full camouflage costumes drifted downstream from the launch ramp while the men took turns pulling the starter cord of a reluctant camo-painted outboard. The store was not open, so I dropped two letters in a mailbox and left. Four miles downriver, where the river swells to over a half-mile-wide at Grassy Flats, the outboard was still drifting and one of the men was still pulling the starter cord.

Thirty-five miles downriver, I approached Louisville. I was tired and my right hand hurt. I kept to the Kentucky shore looking for a place to stay for the night. Behind Towhead Island, I rowed into a marina and drifted by a large twin-hulled cruiser and a man aboard asked if there was anything I needed. I introduced myself to Wayne and told him I was looking for a place to get off the water. He motioned me to I tie up by the office barge. Joe, the harbormaster, said the charge was $8 for one night. I was about to leave and camp in the mud on Towhead Island for free when Joe said Wayne had taken care of my bill. Wayne offered me the use of his boat and after I loaded my gear in his boat a short, bearded man named Gabby appeared and gave me a bit of beef stew. He and his wife and Joe visited on and off that evening. Joe said that when he first saw me, he thought I was “just another nut. This summer two guys paddling a canoe upriver asked to stop and rest at the harbor. They was going to Scruffy’s, it’s a fish-and-shrimp place, dontcha know. Hell, those two guys got a Scruffy’s right in town where they was a-comin’ from. I looked at you and thought ‘here’s another guy headed for Scruffy’s.’” While it was well past my usual bedtime when my last visitors left, I used the marina’s pay phone and had a pizza delivered. I had a very late dinner and stayed up until 1:30 a.m.

I was up at 8:30 and once on the water I headed for the lock in Louisville. The small-craft horn was too feeble to be heard by the lock keeper, so I had to walk to the station. He wasn’t keen on letting me enter the lock. It wasn’t the first time that I’d had to make an appeal to a lock keeper who had seemingly forgotten there is no turbulence in the lock lowering downriver traffic. He asked how much freeboard I had. I explained that the sneakbox was fully decked and he gave me the OK.

Taking a break from the river, I rowed facing forward into Mosquito Creek. If I’d arrived closer to quitting time, I might have stayed. I had no run-ins with mosquitos here or anywhere on the Ohio River, one of the advantages of cold-weather travel.

I stopped at West Point for groceries, got back on the river about 4, and continued rowing into the evening. Mosquito Creek was the sort of place I was looking for, a deep creek wide enough to row up, deep enough that a drop in the river wouldn’t leave me stranded in the mud, but I gambled that there was still enough light left to add to the day’s mileage and find another creek farther downstream. Otter Creek had a railroad bridge over the ravine and a few signs posted on the trees that I couldn’t quite make out but looked like unwelcoming warnings.

At Rock Haven Bend there had been a train derailment that left eight gondolas piled up at the riverbank at the foot of a black avalanche of coal. I drifted by in the last of the daylight and got my flashlight. The chart showed two more creeks 3-1/2 miles downriver. I found the draw where the first one should have been but no water leading away from the river. Rock Run, by flashlight, appeared too small and clogged with brush.

I kept going well past dark. I ferry-glided across to the Kentucky side where there was a distant streetlamp and crept along the bank and found that Doe Run was a creek wide enough for LUNA but there were two nearly submerged trees blocking the entrance. I could have slid over them but a drop in the river overnight would have blocked me in.

I made another 1⁄4-mile crossing of the river to look for Flippins Run but couldn’t find it, either. The lights of Brandenburg on the Kentucky side provided enough light to spot the mouth of Buck Creek. I tied LUNA into a line strung between two trees and cooked dinner on the afterdeck. I settled into the cockpit for the night with the spray skirt cinched over me and held up by the tripod. It started raining and the spray skirt proved to be a leaky roof. I was a bit wet but managed to fall asleep. I slept late and didn’t get on the river until 8. There was a heavy overcast and reports of heavy rain and thundershowers.

My food supplies were getting low and I thought I could shop at Mauckport, just a mile downriver from Buck Creek, but it wasn’t visible from the river. A southerly was with me, and I made good speed to New Amsterdam, but it was also hidden from view.

About halfway down the Ohio, the tendons in my right wrist were inflamed, which made it too painful to row. I taped my hand to the oar handle so I could pull without having to grip it. I rowed like this for three days and that gave my wrist time to heal. When I was hobbled like this I was careful to avoid getting into situations where I might quickly need both hands.

My right hand had continued to bother me; the tendons deep in my palm and forearm ached and my middle finger would often go numb. To take the strain off my hand I taped it to the oar. It seemed to work but only a few dozen strokes later it began to rain. I had to untape my hand to put on my cagoule.

I wanted to get into Leavenworth, but its ramp was too steep and the wakes of tows were swirling around it. I rowed another 1⁄2 mile to a small muddy creek and walked back to town. There were no stores, but I found a café where I ordered a fish sandwich. When I got back to the boat and taped my hand to the oar I was feeling terrible while pounding into the chop of a headwind. After the day’s 31 miles of rowing I stopped in Alton and tucked into a 50-yard-wide tributary mouth for the night.

Leaving Alton, my hand was still sore and weak, and I was not looking forward to rowing, but taped up I managed to get 22 miles downriver to Rome, a cluster of a few dozen houses scattered among cornfields. I crossed the river to Stephensport and set up for the night on the banks of Sinking Creek in the shadow of a tall brick chimney that was all that remained of a house that had burned down.

I slept well, woke dry and warm, and didn’t get up early. I started loading the boat at 7:15; pretty lazy. The river was up 1′ overnight. I took a short paddle up the creek around high-banked bends. Woodpeckers rattled trees all around the hollow. I made a quick stop in Cloverport to picked up Grape-Nuts and Gatorade. As I locked down at Cannelton I met Rosemary and Chauncey as they peered into the chamber. They offered to treat me to a Thanksgiving dinner, so I secured the boat out of the way at the downstream end of the lock. They drove me to Tell City, where they watched as I took advantage of an all-you-can-eat buffet.

The reports I listened to on my weather radio included information about the river levels, and I had to set the sneakbox up to allow for the Ohio rising or falling a couple of feet overnight. Here at Muddy Gut at mile 732, the river was on the rise, which was much less concerning than a falling level, which could leave me stranded in the mud.

At Troy I rowed across the river into Muddy Gut. Its banks were steep, so I decided to sleep in the boat rather than trudge gear up to flat ground. I ran a line between two trees on opposite sides of the creek, tied the boat in under it, and drew a tarp over the line and around the boat. I had more room than I would with just the cockpit tent set. I was settled in at 6 p.m. I would be in this footlocker-sized cockpit for the next 12 hours. The weather reports predicted flooding for the next five days with temperatures dropping into the 20s.

The river rose about 2-1⁄2′ overnight and by morning the line supporting the tarp was just 9″ above the deck. I got underway early, 6:45 by my clock, but I suspected that I might have passed into another time zone; my evenings were seeming a little out of sync. With the river picking up speed, and my right hand healed, I made pretty good time. The biggest tow I’d seen yet went by, 35 barges, five abreast and seven end to end. The land had flattened out considerably and as the water level rose, sky and river were separated by a thin band of land, often bristling with mown cornstalks. On some reaches, the stern of my boat occupied more space than all the land I could see.

By Owensboro I had already covered 24 miles and it was looking like I would have a long day’s run. Along the banks in these lowlands, there were all sorts of summer dwellings elevated on stilts 10′ above ground level as protection against flooding. Even trailers, camper-converted city and church buses, and mobile homes had their wheels hanging in air. Houses with a ground-level floor had a sacrificial look to the lower half, either concrete block or screened-in porches that could be submerged without damage.

The Newburgh locks quickly lowered LUNA 10′ and before 3 p.m. I already had 50 miles for the day behind me. I pulled hard and timed my passage between day markers as LUNA’s wake caught the light and sparkled. I did 2.7 miles in 21.5 minutes—7.7 mph over the bottom. The river gets credit for some of that.

I was hoping to pick up mail in Evansville, but when I rounded the bend 3 miles upstream, my heart sank. I saw skyscrapers and church spires rising above a concrete wall, not a place well suited to LUNA. I rowed past a partially submerged wharf and coasted by some “Diagonal Parking Only” signs up to their necks in the floodwaters and pulled the boat on my throw cushion to keep it off the concrete waterfront access road. I trotted into town. I asked seven people for directions to the post office and never got the same answer. I ran, dodging cars and ignoring stop lights, and made my way deep into town where I found the post office. I got my general delivery mail and ran back to the river and was relieved to find the boat untouched. Sweat was splattered all over the front of my life vest and I was wheezing and coughing.

I carried a dome tent for camping ashore, but there was rarely firm, dry, level ground where I could set it up. I regularly slept in the sneakbox under an improvised shelter from wind and rain. Here, I set my nylon tarp over an oar supported by my camera tripod.

It was time to call it a day, so I headed straight across the river to a vast undeveloped shore and landed 61 miles downstream from my last camp. On the beach I cooked up a can of beef stew then set LUNA up for the night with the blade of one oar propped up with the tripod and the tarp oar to shelter the cockpit.

The following day I rowed 50 miles to a point of land across the river from Uniontown. I made camp on a raft that had been pulled into a grassy field. It blew hard all night, and I didn’t get much sleep. In the morning a front pushed through with rain, lightning, and thunder. I was warm under the tarp but getting wet as the rain drove underneath it, so I got up and started to break camp. The wind-lashed river was very rough, I wasn’t going far (if anywhere at all), but I needed a better place to stay. As I was beginning to break camp, I saw a lone barge coming downriver, obviously adrift. A towboat was chasing after it. With the wind blowing hard across the river the barge was headed straight for my camp. I checked LUNA, she was 15′ from the water’s edge and protected by maple trees standing in a few feet of water.

A storm brought winds so high that a barge was torn away from its moorings on the Kentucky side. It plowed ashore on the Illinois side where I had camped. Its overhanging bow pushed over a tree that came down to one side of the raft where I made a shelter under my blue tarp. The sneakbox, with its red dodger showing here, missed being crushed by a few yards. A tugboat, its wheelhouse and port running light showing behind the barge, had chased after it and took control of it only after it had ground to a stop.

The barge would have to get through them first to get to LUNA. Unloaded and sitting very high in the water, the barge was an impressive mass of steel moving at the pace of a fast walk. The bow nosed into a stand of maples. They shuddered and bent. The top of one came down before the barge eased to a stop. The towboat, the WALLY ROLLER, approached the barge to get a line on it. The 138′ towboat throbbed with the 4,200 horsepower of its two diesels. I stood on the riverbank only 20′ away from it, watching the deck hands muscle a hawser onto the barge. The captain on the PA told them “Get on with it!” as the ROLLER was drifting into the branches. I moved back in case any more treetops might break off. The tow pulled the barge into open water, secured it, and took it back to the dock at Uniontown.

I took all the drama as a sign that I should stay off the river. I walked downstream looking for a better place to camp. I came upon a school bus turned camper, and its owner, Bill. We talked for a bit looking out at the water, which was a real mess. He had a shanty a little farther downriver and said I was welcome to stay in it. During a lull in the wind, I rowed to it and Kenny, another regular at the camp, met me there. He and Bill were going to move the bus and Kenny’s trailer to high ground before the rising river cut the road off.

While we were in the shanty, I happened to look out to the south and said, “Wow, look at that dark cloud!” In that moment, the river below it turned white, as wind shredded the wave tops into spray. I was out the door in an instant to pull LUNA farther from the water. Just before I got to the sneakbox, I heard a loud crack above me as the top 15′ of a tall maple snapped off. I made a quick detour to keep from getting hit by it and it crashed to the ground 20′ from me. I started dragging the boat and, with Kenny and Bill helping, got it under a porch roof to protect it from other windfalls.

I’d been given permission to use this fishing camp while waiting out a dangerous wind storm. The wood stove gave me a chance to dry out all my gear and get a good warm night’s sleep.

The wind had shifted from south to west in the span of a single minute. It was 11:40 and the air was suddenly colder and the temperature would continue to drop into the teens. Kenny drove into Mount Vernon to get some groceries and when we got back the wind was still strong, the water frighteningly rough, and the river still rising. He and Bill left, leaving me with the shanty for myself. It warmed up with a fire in the stove and I had a sponge bath and some soup. The rising water had slowed down, but if I were to be flooded out, I could row over the fields to the north to high ground. The weather radio report was for more high wind so I might have another day here, if the water didn’t run me off first. By 8 p.m. I was very tired after the last night’s lack of sleep.

The fishing camp I was staying in had plenty of firewood but nothing with which to split it for kindling. Before the river had risen, I had seen a hatchet in one of the other camps. I feared the advancing water would be higher than my boot tops so I tied a milk crate to one boot and a child’s classroom chair to the other. I made the trip to the camp and back without getting my feet wet.

It blew hard all night, and I had another day waiting out the wind. It finally dropped after 36 hours of making a mess of the river. It was still very cold—in the 20s with a drop to 10 degrees expected that night. The water was still rising, though not as fast as during the last few days. In the shanty I caught up with some eating, writing, and sleeping.

The entrance to Cave-in-Rock was flooded, so the only access to it was by boat. The gap in the stratum at water level was where I rowed in. If I had stood up in LUNA there, my head would have been even with that shelf of limestone.

The weather had settled down by the morning of my third day across the river from Uniontown. I rowed the 38 miles to Cave-In-Rock where the access to the cave by land was cut off by the high water. The entry, a narrow slot at the bottom of the 50′-high opening, had enough water to float LUNA but not enough width for the oars. All through the 19th century, the cave had been a base of operations for river pirates and a refuge for boatless miscreants. A natural opening in the roof of the cave provided light and served as a natural chimney. It would have been a wonderful place to camp, but it’s a state park and I was more inclined to abide by the rules than had its former occupants.

Cave-in-Rock is 50′ tall, 40′ wide, and 120′ from its entrance to the back wall. A hole in the top provides light.

From Cave-In-Rock, the mouth of the Ohio River was an even 100 miles away. At the confluence, I’d turn south on the Lower Mississippi and speed south away from the advance of winter. I kept moving.

The following day, I passed through the busy port of Paducah, another city best bypassed, and stopped at Joppa on the Illinois side of the river. I didn’t need a ramp to land there. The town’s waterfront park was flooded, and I could just haul out anywhere on the lawn.

Joppa’s riverside parks had been flooded by high water, but the water level was below my boot tops, so the picnic tables worked for me.

The high water had come within a few inches of the picnic-table seats. Square barbecues, their steel dark with rust and soot, stood like channel markers among the trees. The levee that separated the town from the river was capped by a single line of railroad tracks that led to a second bridge that had burned and collapsed into the water.

At the near edge of town, patches of a two-story building’s gray paint had peeled away from equally gray wood. Its twin screen doors’ frames held the last of a screen mottled with rust and as delicate as a camp-lantern mantle. Over the door was a chalky metal sign, “Hop on in for Bunny Bread,” but not much was hopping in Joppa. Across the street a hand-painted sign misspelled “Notory Public” in letters that would have more appropriately spelled out “Clubhouse, no girls.”

Three blocks into town I was wrapped in an eye-watering stench of fermenting manure that wafted from a trailered agriculture implement, a long barrel open along its length on top. Inside was an axle with lengths of chain to flail a load of soupy cow manure and send it flying in all directions. I had to squeeze my nostrils closed. I crossed the street to the grocery store and picked up a can of beef stew. On a shelf of breakfast cereals, an orange box of Wheaties caught my eye with its picture of Olympic-champion gymnast Mary Lou Retton, fists thrust above her head, her smile wide and radiant. I caught myself staring and suddenly her radiance and enthusiasm made me uncomfortably conscious of my grubby appearance and my fatigue. Having that box of cereal in the boat would only make me feel worse.

At the end of my last full day on the Ohio, the only place I found to get off the river was a wide-open flooded field. I wore my cagoule to shield me from a bitterly cold wind.

I’d made a cover that was supported by the cockpit hatch and a pair of struts. It was effective in keeping me warm and dry when it was the best choice for a cold and windy last night on the Ohio, but it offered very little space for moving around. In the morning, the water covering the field here had iced over.

On my last day on the Ohio River, I had reached the 980-mile mark on my charts and could see the Mississippi sweeping the horizon on the far shore opposite the Ohio. I pulled ashore in Cairo with my empty two-liter soda bottle to get some water before pushing LUNA’s bow into the river that would carry us 870 miles to New Orleans. I found a tavern that I thought would let me have some water and walked in. The moment I stepped inside conversations stopped and everyone turned to look at me. I hadn’t brushed my hair or shaved for several days and was wearing my faded PFD and my mustard-speckled wool pants. As the bartender kindly filled my water bottle, a man at the bar wearing brown and green camouflage looked me up and down:

“What the hell you been doin’?”

“Rowing.”

“Is that all?”

I told him that I had rowed from Pittsburgh and was next headed for New Orleans. He looked away across the bar top.

“I feel sorry for you on that damn Mississippi.”![]()

Coming in the February issue: The Lower Mississippi River; March issue: The Gulf of Mexico.

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Chris – this is the second time I’ve read of your adventure recreating Bishop’s historic journey. I’d forgotten just how miserable the conditions were on the Ohio, and yet you had the will to take the time and make the effort to stage these terrific photos of your circumstances. The closest I’ve come to this kind of solo endurance venture is a cross-country bike ride, but I chose an easy route from east to west with the sun and wind at my back during early autumn, and a cheap motel with a hot shower at the end of each day’s run. How on earth did you stay motivated to keep going?

I agree, very miserable. Instructive though on what to avoid.

Really a great story, Chris. I could smell the mud, feel the wet cold and also the exhaustion and loneliness of such a voyage. It reminds me of my trips at Allier and Loire in my youth (1990).

Your story is very reminiscent of Brinker Buck’s “Life on the Mississippi.” He built (or had built) a flatboat of about 30′ length with a good-sized deck house and followed pretty much the same route you did, all the way to New Orleans. He always had a crew of two or three people, but personnel shifted in and out as he went on.

He travelled in summer, and of course had the capacious cabin to shelter in. He mounted a good-sized outboard engine for maneuvering as well as propulsion, and surprisingly enough, never seemed to have the engine conk out at critical moments. His main issue was dodging barges and tow boats. Though he had been warned that currents on the river would prove to be his undoing (i.e. “deadly”), he found them quite easy to deal with, thanks to the outboard. Like you, he came across many friendly and helpful people along the way, and was often invited to moor overnight at marinas and state parks.

What an experience, thanks for sharing. This line, emblematically bleak, has stayed with me: “I was again tired to the point where I would stand for long spells trying to remember what I was supposed to be doing.”

A stinkin’ fine tale, Chris. Grand foundation for a bit more comfort later in life.

Wow! what a great adventure, so perfectly captured in your photos and writing… I can’t wait to read more!

I take my hat off to you Chris. I would have given up so many times!

A fine tale, Chris, wonderfully told.

Great adventure, but I’m shivering as I read it. Nicely told!

What Richard Kuttler said:

“Wow! what a great adventure, so perfectly captured in your photos and writing… I can’t wait to read more!”

Great story, Chris; it’s the second time I read it. The mud sounded miserable, reminding me of several places we stopped along a trip down the Yukon, which I was happy to see didn’t have the trash floating in it like the Ohio. I was interested to read about the Hubbards. Shantyboat was one of the first “cruising” books I can remember reading–two or three times over the years– at my Grandparents’ house. They lived next door to Harlan’s brother, in New Rochelle, NY. whom I met a few times as a little kid. Small world. I can’t wait to read the next installments.

I grew up in Pittsburgh in the 40 and 50’s. I spent many hours on the Allegheny and Mon and the Ohio only as far as Wheeling. We used to joke it was impossible to drown in the Mon because you would dissolve first from the pickle acid pumped out of all the mills. The Allegheny wasn’t as industrial but it was full of brown pike and Allegheny white fish. For you non-river rats these weren’t actual fish but you’ll have to use your imagination

What an adventure. The story has motivated me to try to find a similiar one. I’m 79 years of age now so it will have to toned down a bit, but thats ok. Your adventrue is inspirational.

I plan on doing the Rideau canal system this coming spring. Not sure what kind of boat yet.