For the past 35 years I’ve built dozens of small boats, and all of them have been made of wood. I did, however, make one small foray into making a fiberglass boat. I had carved a 12″ model of a Whitehall by eye from a fragrant, fine-grained piece of Alaska yellow cedar, and while it was pleasant to work and I enjoyed having the hull shape gracing my living room, I had to keep it out of the incautious hands of my two young children. I decided to splash a fiberglass mold of the model and produced a couple of ’glass hulls to give as toys, confident the composite reproductions were tough enough to hold up to their rough use. Gig Harbor Boat Works evidently had the same idea: a composite Whitehall would have a significant advantage over a wooden one; you could do almost anything with it and not have to fret about the easily damaged woodwork.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe Whitehall has an uncluttered, easy-to-clean interior. The sliding thwart offers the rower freedom of movement from side to side and keeps its tracks out of the middle of the boat where those of a standard sliding seat would be in the way of getting in and out of the boat.

The company, founded in 1986, is based in Gig Harbor, Washington, and produces small composite boats inspired by traditional small craft of the 19th century. I recently paid a visit to the Boat Works to try their 14′ Whitehall. It has the appearance of a lapstrake hull, typical of the Whitehalls built in New York prior to 1850. The top three strakes have distinct “laps” that accentuate the hull’s curves and below that the “strakes” are defined by subtle chines, providing a smoother underbody to reduce drag. A molded keel runs from stem to skeg to aid in tracking and the depression it creates inside the cockpit creates a narrow channel to direct bilgewater to the drain.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe footboard can be set in one of three pairs of slots for sliding-seat rowing or fixed-thwart rowing or removed to let the bulkhead serve for fixed-thwart tandem rowing.

There are two standard layups available, and both are hand layups with polyester resin and gelcoat. The basic version is fiberglass roving and the lightweight version, featured in this review, is a biaxial fiberglass cloth over a Divinycell foam core with Kevlar reinforcements in the high-stress areas. The standard gunwale has a tough vinyl extrusion. For a touch of brightwork, the gunwale is available in red cedar with sapele accents.

Sealed compartments in the bow and stern provide seating for passengers and flotation to keep the boat afloat when swamped. While airtight compartments come in handy for stowing gear out of the weather, U.S. Coast Guard requirements don’t allow the manufacturer to install hatches in compartments that are designated for flotation. Both compartments have small holes drilled in their bulkheads to equalize air pressure so you can drop a hot boat in cold water or trailer it over a mountain pass without stressing the hull. The holes might be rather inconspicuous left as they are, but the small polished stainless-steel covers fastened over them are a nice touch. There are four chrome-plated brass fixtures are for hanging fenders.

Christopher Cunningham

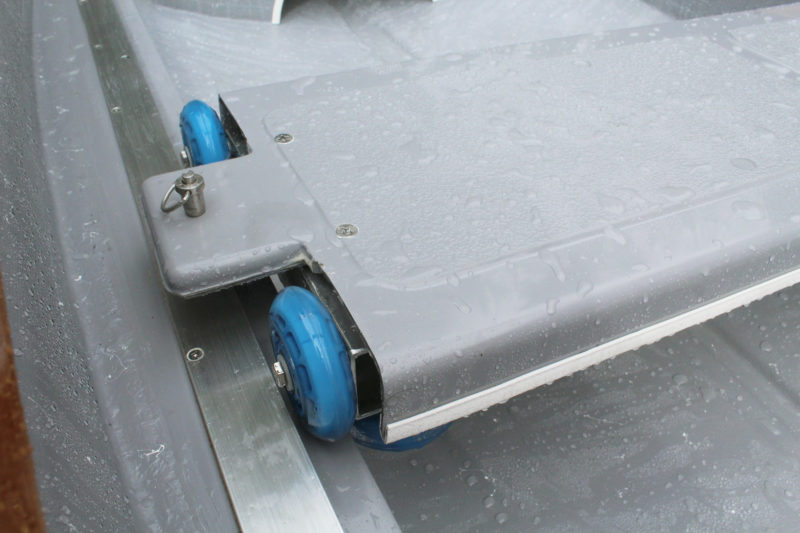

Christopher CunninghamThe sliding thwart rides on rollerblade-style wheels with soft tires for smooth rolling and UHMW/nylon corrosion-free bearings. Note the wheel beneath the seat, one of four that centers the thwart. Locking pins can engage holes in the flange to lock the seat for fixed-thwart rowing.

The sides of the aft compartment extend to the forward thwart, creating a pair of parallel ledges that serve as the tracks for the sliding seat. The sliding seat is a standard feature. It has roller-blade-like wheels with nylon/UHMW (ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene) bearings that won’t corrode in a marine environment. The space between the side benches in the stern have a series of three slots for a foot board that is held in place by a pair of removable pins. Loops of Velcro to hold the feet for sliding-seat rowing are about as simple as they can be yet easily adjusted and entirely effective for holding feet in place—even if you rush the slide on a quick recovery.

Matt McKendry/Katie Malik

Matt McKendry/Katie MalikThe Whitehall could support me when I shifted up against the side.

Areas of non-skid texture are molded into the interior of the hull and the tops of the seats, so I had good footing getting in and out of the boat. The stability was reassuring, and I could drop down from a dock into the boat without feeling unsteady. I could shift to one side of the sliding thwart right up to the gunwale and still have just enough freeboard and reserve stability to maintain my balance. The sliding seat can be locked in an aft position for tandem rowing or amidships for solo fixed-thwart rowing.

Matt McKendry/Katie Malik

Matt McKendry/Katie MalikWhen I rowed solo with the sliding seat, the stern settled at the catch…

Matt McKendry/Katie Malik

Matt McKendry/Katie Malik…and the bow came back down at the finish. A bit of ballast in the bow—cruising cargo or a drybag filled with water, perhaps—would improve the trim.

I started my afternoon of sea trials with solo sliding-seat rowing. The Whitehall’s 55″ beam provides enough span between the standard silicon-bronze oarlocks to row 8′ -long oars effectively without an overlap of the handles. I maintained a GPS-measured 4 knots at a relaxed pace, 4.7 knots at an aerobic-exercise effort, and hit 5 knots in a short sprint. The boat felt good while I was rowing, but I noticed in the photographs that the bow lifted above the water at the catch when my weight was aft and returned to the water at the finish of the stroke when I leaned toward the bow. I had set out with the foot board in the aft pair of slots setting my weight farther aft than it could have been at the forward slot and with my legs extended, there was more run left on slides. If I had used the forwardmost position for the footboard my weight would have positioned about 6″ farther forward. That might not make an appreciable difference, but if there is any gear or water ballast to be carried aboard, the additional weight should be set well forward.

Matt McKendry/Katie Malik

Matt McKendry/Katie MalikThe Whitehall trimmed nicely while rowing tandem with the sliding thwart locked in place.

The Whitehall tracks well and I never had to adjust my course by pulling harder on one oar than the other. Turning 360° in place took only seven strokes—pulling on one oar, backing the other—several fewer strokes than I expected. The cutaway skeg evidently helped strike a good balance between tracking and turning.

Matt McKendry

Matt McKendry With the rower at the forward station, a petite passenger can sit in the stern without putting the Whitehall out of trim. The boat is better off with a larger passenger sitting on the sliding thwart.

With a partner taking to a second pair of oars at the forward rowing station, I slid the sliding thwart to the aft position and locked it there with a pair of pins. I took the footboard out to use the aft compartment’s bulkhead as a foot brace. The spacing between the tandem stations is a bit tight, but it didn’t take long for the two of us to adjust the length and rhythm of our strokes and row well together without clashing our blades. We did 4.3 knots at a relaxed pace, 5.2 knots at an exercise pace, and 5.5 knots in a sprint; good numbers for a 14′ boat.

I switched places with my rowing partner and took the bow station while he sat in the stern as a passenger. Although he sat as far forward as he could on the aft seat, I could tell the Whitehall was down by the stern and my top speed was around 4-1/4 knots. When he sat on the sliding thwart, still locked in its aft position, the trim improved, and I could do 4-¾ knots.

Matt McKendry/Katie Malik

Matt McKendry/Katie MalikWith two aboard providing some weight to keep the bow down, an outboard, especially a lightweight quiet electric one, makes sense for the Whitehall.

The early Whitehalls were built a half-century before the advent of outboard motors and their distinctive wineglass transoms, set high above the water with only the ends of the skegs in the water to support them, were designed for rowing not motoring. There’s no volume in the stern to support an outboard let alone an operator sitting next to it. We mounted an EP Carry electric outboard on the Gig Harbor Whitehall; at 21 lbs, the motor is about as light as an outboard can be. With only an operator aboard, keeping her weight as far forward as possible, the Whitehall moved along at a good clip, but the bow was out of the water. For the operator, that might not matter much—the motor is doing all the work. An outboard tiller extension would make it easier to operate the motor from a position closer to the middle of the boat (although an EP Carry’s throttle won’t fit a standard extension). Bringing a passenger along will hold the bow down and motoring for two with a quiet electric motor could make for a very pleasant outing. With two of us aboard, the EP Carry could push the Whitehall at 4 knots.

Before we pulled the Whitehall out of the water, I wanted to see if I could lift it. I stood amidships, set the turn of the bilge on my thighs, and leaned back. The Whitehall rose clear of the water without much effort on my part. I wasn’t tempted to do more than that, but I was impressed that the boat’s 125 lbs was so easy to handle. Two adults should be able to lift and walk with the boat if that’s required. A popular option is a stainless-steel keel guard to take the worst of the wear when the Whitehall needs to be dragged ashore. The weight of either of the hull layups result in a boat that can be launched from and reloaded on a trailer singlehandedly.

Making a composite Whitehall was a good idea, not only for the toy boats I made but also for the 14′ Whitehall Gig Harbor has produced. The care I’m compelled to take with the New York Whitehall that I built in the traditional manner limits what I do with it and the Gig Harbor Whitewall performs just as well, if not better. It is lighter, tougher, and better suited to rugged service.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats.

14′ Whitehall Particulars

[table]

Length/14′

Beam/55″

Weight, Fiberglass/145 lbs

Weight, Kevlar-Composite/125 lbs

Sail area (optional rig)/Main 57 sq ft, jib 28 sq ft

Outboard rating/ 2 hp

Capacity/3 passengers, 492 lbs

[/table]

The 14′ Whitehall is available from Gig Harbor Boat Works. The base price is $6,995. A sailing version is available for $10,295. Options and accessories are available.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I had a GH Whitehall, from about 15 years ago until sold recently. It was a great solo rowboat, and I just wanted to say more on the slide seat design. The usual drop-in slide seat rigs have to be mounted into the boat and take up significant central space. They usually have a racing style rowing seat, and typically small, hard plastic wheels. The GH design works if the boat has side seats to carry the tracks, and enough beam for the oarlocks to mount on the gunnels. The advantages are that the seat lifts right out to leave a clear cockpit (great for camp aboard), it has large soft wheels that are quiet and long lasting; the surface can carry a racing seat if you want but works fine with a cushion, and it locks easily to become a fixed seat (good for rough conditions). I found mine so useful that I copied the concept on my home-built cruising rowboat.