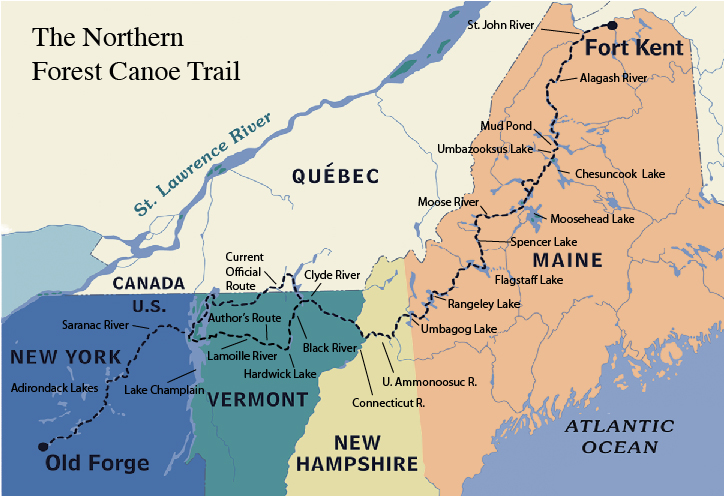

"Is that really necessary?,” I teased Andy, pointing to the tripod strapped to his pack. Andy, a veteran Outward Bound instructor, was the first of several paddling partners to accompany me on the journey I was about to begin, the first through-paddle of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail (NFCT), on May 1, 2000. In the original incarnation of this adventure I had imagined Andy and I would travel the entire 740-mile trail together, but his ties to his wife and work precluded him from making the full trip. I’d rendezvous with other paddling partners along the way and paddle solo in between.

TINTIN, my 16′ wood-and-canvas canoe, floated at the dock in Old Forge, New York, and with each armload of gear we loaded I watched the freeboard dwindle. I’d built the E.M. White canoe for this trip under the guidance of Maine builder Jerry Stelmok. My goal: cross the Northeast in a single season, under human power alone, following the Northern Forest Canoe Trail. The then-nascent water trail links a series of shorter routes used by Wabanaki natives and early European settlers to travel the region between New York’s Adirondacks and northernmost Maine. The trail is now well established and supported by a non-profit organization (see sidebar below).

“Like you’re going to use that axe,” Andy replied. I’d found the axe head rusted and abandoned the previous summer and refurbished it for this trip. While an axe was an odd accompaniment to my Leave-No-Trace ethic, it was the traditional tool for wilderness canoe travel—so I packed it. Though I’d been trained as a low-impact camper, I was fascinated by the era when the canoe was king, and Voyageurs were masters of woodcraft and living close to the land. I had imagined that my trip would have some of that raw quality, but I was hoping to do without the common Voyageur maladies of compacted spines and hernias.

At 28, I was still living with my mother when I wasn’t working for Outward Bound. My friends found this odd, but my Italian grandfather assured me that when he was a boy the practice of living with a parent at my age was standard fare. On the dock, I felt in my gut what I saw in my mother’s watering eyes, but in my last-minute frenzy culminating six months of planning, I pushed my sadness aside. I had taken plenty of backcountry trips, but never one as long as what lay ahead of me.

NFCT/SBM

NFCT/SBM.

I dipped my fingers into the water and shivered. The lake was free of ice but surprisingly cold. Andy and I took our first strokes and glided away from the dock, passing rows of boarded-up summer cabins that lined the narrow lake. The still-bare branches arching over the shore looked brittle; the dull brown water barely rippled at our passing. TINTIN was the only boat on the lake. I turned several times to wave to my mother. She remained on the dock until we were out of sight.

Andy and I rode a wave of euphoria through the serene and sparsely populated Adirondack woodlands where lean-tos outnumbered cabins. But our spirits began to sink shortly after we portaged through the small urban center of Saranac Lake and launched in the Saranac River. The river’s rushing water brushed TINTIN’s hull with a line of scum; to replenish our supply of drinking water, we’d have to detour into the adjoining untainted wetlands. I was determined to treat my trip as a wilderness expedition by living off the supplies we carried and the water nature provided, so I refused to climb the riverbank and request tap water from the homes we passed. Grocery shopping was also out, even though the route occasionally intersected towns with markets.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenFulton Chain, Adirondacks. This lean-to is typical of the camp shelters scattered throughout the Adirondacks. I had been keeping my red food sacks in a canvas Duluth pack, but one night, while the Duluth rested inches from my head, mice sneaked into the Duluth and chewed straight through a stuff sack full of GORP and granola. We tried hanging the stuff sacks but that didn’t entirely eliminate the problem; we just wound up with critter piñatas.

The lower Saranac brought a succession of portages around dams and Plattsburgh’s urban clutter of bridges, noisy riverside roads, and industrial buildings before dropping us into Lake Champlain at dusk. Under cloudy skies we paddled south, hugging the shore as the lake unfolded to the east. After eight days without a rest my body ached, but I forced myself to maintain our tempo. Just before dark we reached Valcour Island, hauled our gear up to an exposed ledge, and erected the tent on a spongy, pungent bed of pine needles. South Hero Island, our next goal, lay 3 miles distant, a pencil line of land on the horizon. We’d need calm conditions for the open-water crossing.

“If the weather’s good tomorrow, we’ll have to go,” I said to Andy, secretly hoping that he’d persuade me otherwise or that rain, lightning, an earthquake—anything—would grant us a day off. Lightning pulled through and confined us to the thickly wooded island the next morning. I slept until noon. When the rain broke, I made chocolate-chip chapati bread while Andy inspected the torn canvas and gouged shellac on what had once been TINTIN’s unblemished hull.

Andy Chakoumakos.

Andy Chakoumakos. Fulton Chain, Adirondacks. Those first few days are a blur. I was so charged that sleep and food felt more like atmosphere that I passed through then anything that consciously required a stop. I leapt at any chance to practice my burgeoning outdoors skillset. Once I wielded my refurbished axe, whacking wildly at a spindly blown-down, another time I planted my pole and surged through a rivulet that connected to lakes in the Fulton Chain as though I were Benedict Arnold ascending the mighty Kennebec River.

The following day, under a grimy sky, we paddled to South Hero Island, surviving the longest crossing of the trip—a challenge that had worried me since day one—and worked our way north along the east side of the island. The shoreline was a sheer slab with no place to land, but after the crossing I felt much less anxious having solid ground nearby. I was even a bit cocky after our recent success, and it took me a while to notice the growing swells that were piling past us.

Andy dryly noted “a bit of chop, dude,” as TINTIN teetered on the crests of passing waves. As he strained to keep us upright, his blade barely left the water between strokes.

TINTIN’s stern bucked out of the water and I found my blade swinging through air. I pressed my knees into TINTIN’s flanks and leaned down to connect with water. The rough paddling was exhilarating until TINTIN was propped up on the back of a large wave and I found myself looking down at Andy’s head. Snapped sober, I traced the shore for a safe landing. A mile in, there was a break in the South Hero shoreline, and I took aim for the pebble beach there. After we’d hauled everything ashore, we climbed the bank and headed to the nearest home. A grumpy, half-shaven man burst onto his porch. Once we explained ourselves, he was kind enough to offer us a spot on his lawn for the night.

Andy Chakoumakos

Andy ChakoumakosFulton Chain, Adirondacks. All told, I portaged nearly 70 miles. I had long held that portaging offered necessary balance to the lifestyle of the canoe tripper, providing the paddler with a break from long hours of sitting. Admittedly, I became attached to portaging. Ever challenging myself to carry TINTIN yet a little farther without stopping. When the going got rough on the water, carrying was my reprieve.

The next morning we made the 1.3-mile crossing to the Vermont mainland and pushed our way into the mouth of the Lamoille River. Days of rain had flushed a brown sediment-rich cloud into the lake. We inched upriver against a flood of current. High water swirled around tree trunks. We had no place to hide, no eddies to protect us. Poling was impossible. After two hours of hard paddling, my neck was electrified with pain. Near breathless, I grabbed a branch to hold TINTIN in place and give us a break while Andy filled his empty water bottle in the murk. Would the river be this brutal for all of its 75 miles? Andy was scheduled to leave the following day. Barbara would replace him, but she only had five days to paddle. It would be impossible to ascend the Lamoille alone; I pictured myself in a desolate swamp, creeping upriver one tree branch at a time.

After a single frustrating day fighting the current, we reached a small gravel boat launch in East Georgia, where I said goodbye to Andy and welcomed Barbara aboard. She ran the Outward Bound base where Andy and I worked. That first afternoon aboard TINTIN, she looked me straight in the eyes and declared, “Let’s get you off this river!” We charged upstream, and soon reached a 3-mile portage around a series of rapids. Barbara carried the Duluth pack, filled with fresh supplies and as heavy as lead. On our second day we continued to fight a powerful current. I shoveled water madly in the stern and Barbara put her back into every stroke. I couldn’t bear to look directly at the bank—I could see clearly enough in my peripheral vision that our progress upstream would have scarcely outpaced a slug. I tried poling but abandoned the attempt after a mishap sent us careening broadside to the current.

Andy Chakoumakos

Andy ChakoumakosForked Lake, Adirondacks. Long-distance paddling provides endless opportunity for idle chat, proselytizing, and banter. Andy told me about boyhood fishing trips with his uncle. The outings started early and the fishing was OK, but what really made his day was having grinders for lunch. When we paddled past a tiny island chapel I spouted, “I would go to church there!” before trundling off on a “God as nature” tangent. Later, a floating stick felt like undisputable proof of my belief in wood’s superiority for canoe construction. Andy wasn’t convinced.

As we climbed higher into the Lamoille watershed, the banks were dotted with dandelions and the river wound through bright green farmland. The inside bends of the river held precious slack water where we could rest. Beyond the north side of the river, cropland snugged up to wooded ridgelines, a glimpse of the Green Mountains that run the length of Vermont from Massachusetts north to the Canadian border. The floodwaters had begun to recede, but even so the Lamoille never allowed us more than 10 miles a day. When Barbara waved goodbye along a quiet stretch of river, the full height of the land was still ahead of me.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenAfter Barbara and I had to part ways I had to take on a waterfall and three sets of rapids—all within the span of one mile. That portage around the falls was up a sheer wooded bank, but beyond that the river was only knee deep. I just hopped in and hauled. Little was going to stop me from reaching Hardwick Lake and putting the longest, upriver component of my trip behind me.

After a final day of hauling TINTIN upstream, I reached Hardwick Lake, a 1 ½-mile-long finger of water snugly balanced between the abrupt sides of a conifer-draped valley. I raised my arms and hollered with only TINTIN to hear me—Hardwick was my farewell to the Lamoille River and the end of my week of toil.

At the far north end of the lake, I paddled into a stream about the width of a bathtub, ducked under some wire fencing, and soon found myself in a rocky meadow. As the setting sun grazed the treetops, I bumped into a tiny culvert bearing a dirt road that connected the steep valley sides. Beyond the culvert my stream disappeared into a tangle of alders. I was tired, wet, and needed to make camp.

I hopped the fence, and followed the road to a white farmhouse, the only building in sight. A collection of horse tack framed the front door. A dark-haired woman answered my knock, and after I explained my predicament she gave me permission to portage out of her pasture. I mentioned that the only hospitable tenting spot I had noticed was an open bluff about 100′ up the other side of the valley. She replied flatly that the property wasn’t hers and left it at that.

I shuttled everything to the roadside below the bluff and was bent over a pack when I heard tires crunching on the gravel behind me. I spun around as a blue pickup threw a cloud of dust over my gear. I was an odd sight with my packs and canoe: the only water within reach was the unnavigable stream. The passenger’s window rolled down. In the shadowy interior sat two large men and despite the dim light, I couldn’t miss the gleam of the shotgun placed between them. The passenger’s gaze was fixed upon me.

“What ya doing?” he asked casually.

“I was going to camp up there.” I immediately chided myself for stating instead of asking.

“No you’re not.”

My legs began to shake.

“I’m doing this crazy trip,” I blurted. “I’m headed to Maine.”

“Maine?” he said with contempt. “How are you getting from here to Maine?”

“From Lake Elligo, I’ll paddle to the Black River,” I talked fast, suppressing tears. “The Black will take me to Lake Memphremagog, then up the Clyde River and down the Nulhegan to the Connecticut…” His face softened. Still, he told me I couldn’t stay, but offered me a ride a mile and a half up the wooded valley road to an old tote road that would be suitable for camping. I thanked him, but declined the ride, and as they sped off, I readied for another portage, my fifth of the day.

Having walked 4 ½ miles to make the 1 ½-mile portage of canoe and gear, I slapped up my tent in the glow of my headlamp. I slid into my sleeping bag and scrawled in my journal “Will my body function in the morning?” I quickly fell asleep.

Andy Chakoumakos

Andy ChakoumakosRaquette River, Adirondacks. Lining, like portaging and upstream hauling, became comfort measures. When paddling simply wasn’t working, I fell back on what would. Progress was slow, but anything that kept me moving was enough to boost my spirits.

The Black River offered several days of welcome downstream travel. I meandered through cow pastures and took a rest day in a tucked-away pine grove. I found a pay phone and called my mother, who shrieked when she heard my voice. She told me that adolescence had been extended until 29. I knew she meant it as a vote of confidence, but all I could verbalize was a mumbled thanks. A day later, Cristina, a fellow Outward Bound instructor, joined me as we turned up the Clyde River and got blasted by what the map indicated as four consecutive contour lines’ worth of elevation gain. I had known that the Clyde would be against the current, but I had never studied the map closely enough to prepare myself for the true onslaught. All day long we were waist-deep in the water, lining TINTIN upriver.

“Was the Lamoille this bad?” Cristina complained.

No, I had to admit. Even the Lamoille let up now and again, but the Clyde remained constant for miles. At one point, we crept beneath the massive buttress of a cement bridge where cars rattled overhead. Cristina stuck it out with me until the river plateaued on a confusing wetland and I again had to part ways with another friend.

I went on alone, and suffered one final parting kick on the Clyde: 12 mind-numbing blowdown-induced portages in the span of two hours. Along the roadway portage to the Nulhegan, a policeman pulled over and for some odd reason, asked me if I owned my canoe. Our whole exchange took place while I had TINTIN weighing on my shoulders.

When I reached the Connecticut River, a wide-open channel warmed by a burst of evening light, it felt like a gift. I followed the Connecticut’s looping meanders south, then headed east on the Upper Ammonoosuc River. I regained my confidence with poling as I ascended its shallow waters into New Hampshire. The canopy overhead nearly blocked out the sky. The click of my pole on the pebble bottom startled a moose into a cross-river trot, water splashing around its knees. The corridor of diffused light brought a memory of a boyhood fishing trip with my grandfather and for the first time since the Adirondacks I felt at peace with the landscape.

Two days later, I was plowing east on a portage through a sea of spindly trees trying to find my way to the Androscoggin River. My tote road had petered out long ago. When I wasn’t tripping over roots, I was being slapped in the face by branches. And there were mosquitoes, lots of them. In a fit of exhaustion I tossed aside one of the two packs I was carrying and pressed on with the other. When I finally broke through to a logging road that would take me to the Androscoggin, I dropped the pack and without a moment’s rest reentered the overgrown jungle in search of the Duluth I’d abandoned. Five hours later, I had trudged just 4 1/2 miles and was back on the edge of boulder-strewn Phillips Brook where my portage began. I still had to get TINTIN across, but it was dusk. My supplies were with the packs and I had little energy. There was an empty yurt nearby, and after eating the last of the hummus in my day bag, the only food I had with me, I spent the night shivering in the yurt. The following morning, my ordeal continued, brightened slightly when a fisherman passing through told me that his grandfather remembered Native Americans using this same portage.

One month from the day I left Old Forge, I made the 2-mile crossing of Umbagog Lake’s remote northern bay, and traversed the watery border into Maine. I put on my only piece of unsoiled clothing, a blue-and-white-flowered Hawaiian shirt, and celebrated entering my home state and reaching the halfway point of the trail.

I clambered up the high bank at the mouth of the Rapid River and prepared for the 3-mile carry around the river’s Class III and IV whitewater. The trail wound through a cedar grove before climbing to drier ground and leaving the river’s tumult behind. A few hours later, I stopped at Forest Lodge, which sits on a hill overlooking the river. I stood by a pair of Adirondack chairs and gazed down a green lawn as it dipped to the trees that cloaked the churning waters. In the 1930s and ’40s, author Louise Dickinson Rich lived at the lodge. I had read her first book, We Took to the Woods, and been charmed by her tales of homesteading in the Maine woods of yesteryear. Louise, looking out from this same viewpoint, had witnessed everything from the whitewater fanatics of her day to one of the last long-log drives in the East.

Andy Chakoumakos

Andy ChakoumakosSaranac River, near Clayburg, New York. I had just turned down Andy’s offer for a spell from carrying when a pickup pulled over to offer us a ride. I knew that Andy and I were aligned in our refusal to accept a lift, so I just kept walking and let him talk. Andy mentioned where we’d come from. “You’ve come all the way from Old Forge?” The driver said, dumbstruck. Then his face wrinkled in bewilderment. “Suit yourself,” he snapped and screeched off.

Three days later, I paddled into the lakeside town of Rangeley to begin the 4-mile portage between the Androscoggin and Kennebec watersheds. Feeling strong enough to give double-packing another go, I plodded along the path over grass and then pavement. While passing a municipal tennis court, a red-haired and bearded man motioned to me.

“You’ve got quite a load,” he said.

“I’m doing this trip…”

“The Northern Forest Canoe Trail!” he beamed.

I was shocked to hear the name spoken aloud in connection with my efforts. At the time, the nonprofit organization devoted to the trail was barely months old. The trail wouldn’t officially open until 2006.

His family, a cherubic red-haired daughter and son and his soft-spoken, striking wife, joined us. The man put his arm around his son and grinned, musing that someday the two of them might paddle the trail.

“Did the Lakes have enough signs?” he asked.

I chuckled. Except for a few placards along the Saranac River in New York, the trail was unmarked with the notable exception of western Maine. He told me that he’d helped to post the signs throughout the Rangeley region. I wondered if he might have been responsible for putting up the very sign that had introduced me to the existence of the trail several years before while I was leading a trip for Outward Bound and set me on the course that carried me to that day.

A drizzle set in as I parted ways with the family. The simple kindness and encouragement they extended was a pleasant contrast to my solo travel and reminded me that my journey could resonate with others.

Another week of solitude passed. The rainy spring was over. The South Branch of the Dead River was impossibly strewn with rocks. I threw up my arms as I bounced between the boulders. Even before these new scrapes, TINTIN had stayed about as dry as my leaky boots. I was forced ashore every couple of hours to drain the puddle that lapped at my toes. Even though the Duluth grew lighter by the day as I gobbled a potful of dinner each night, I began to feel the dead weight of my little-used axe.

In the midst of paddling the windblown 21-mile length of Flagstaff Lake, I took a rest on a shrubby island and stumbled over old chunks of pavement, the remnants of a road that led to the village of Flagstaff before the Dead River valley was inundated by the building of a hydroelectric dam in 1950.

Andy Chakoumakos

Andy ChakoumakosLamoille River, Vermont. As we loaded gear back aboard TINTIN in the quiet water above this dam, a man out walking his dog made a passing comment about a wild ride down the river. I was about to correct him, but Andy got to him first: We were traveling up river, not down. The man’s eyes grew wide with disbelief. I felt a rush of pride, not just because the stranger was impressed, but because Andy had taken ownership of the trip. It had become ours.

The next day, I heard the rumble of Grand Falls long before I ground ashore to make the portage. Below the 30′ falls and afloat once more, I poled up wide but shallow Spencer Stream and took the first tributary that I found, expecting it would deliver me to Spencer Lake. After I’d traveled for an hour up the small stream, the dense forest leaned in and threatened to swallow my narrow corridor. I had passed a spot where my map indicated there would be a bridge, yet I’d seen nothing there but woods. I worried that I had turned up a forgotten branch of the stream and would miss the lake and the rendezvous with my next paddling partner. Determined to arrive at the lake by evening and trusting my intuition to continue driving farther upstream, I leaned into the pole and thrust TINTIN up the rivulet, sliding past moss-covered banks. Eventually, the channel widened and I entered a pool where I was reassured by the sight of a fisherman on the far shore.

At dusk I portaged around the cracked timbers of a leaking dam into Spencer Lake. The black flies descended, and I couldn’t get TINTIN back into the water fast enough. I fled to the middle of the lake and only then did I have a moment to take in my surroundings. Ridgelines layered in mist ascending upward cupped the isolated lake. I could see a single lodge built into a nearby hill; the remainder of the tree-lined shore was uninhabited. A sandy spit sprinkled with polished stones arced into the lake. The sounds of TINTIN’s wake and the water dripping off my paddle blade mixed with the hum of distant peepers. On the spot, I promised myself that I would return.

The 5-mile portage to the Moose River was the longest of my entire route; it would take all day, packs first, then TINTIN. Fortunately, I had help. Jodi, the office manager at the base where I worked, had joined me. From the north end of Spencer Lake, we followed a logging road east, then north toward the Moose. Gear aside, the walking was easy. Slash-covered clearings occasionally marred the scraggly roadside forest. I’d been on my own for nearly three weeks. Starved for conversation, I launched into an episodic narrative. I babbled for over an hour before the first wave of embarrassment spread over me, but the urge to speak was uncontrollable. Normally, I was a sensitive conversationalist, but my weeks alone had changed me.

By day’s end, with the portage behind us, we camped above the Moose River. To celebrate, we built a campfire. In my effort to tread lightly on the land, this was only my second fire. My neck was stiff and my legs weak from the 15 miles of hauling.

Jodi Hausen

Jodi HausenSpencer Rips, Moose River, Maine. It became pretty obvious that the axe wasn’t necessary, but I couldn’t imagine making the journey without it. My goal wasn’t simply to paddle the trail. I had to do so with an ethic that honored the past, even if it made the trip harder than it had to be. The axe was my link to the era of the Voyageurs.

Thwack!

I drove the axe into a piece of firewood. Previous campers had left several chunks of split wood. I was slimming a couple down to kindling size.

Jodi was stacking birch bark and twigs in the fire ring. I placed another piece on the splitting stump and raised the axe high.

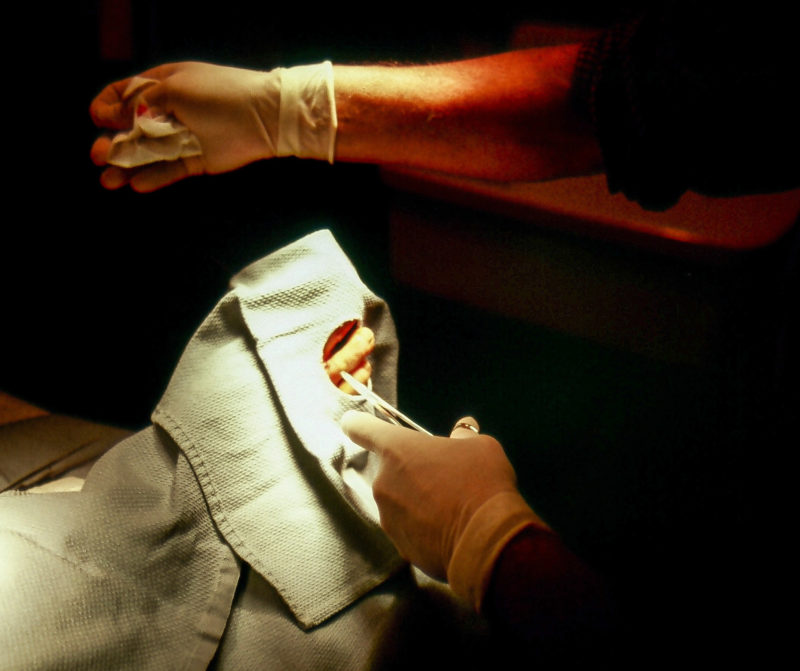

Chink…thunk!! It was the wrong sound. The wood fell away. Then I shivered, as though I’d stepped from a sauna into the sub-zero air of winter. I felt the cool metal blade in my foot, but the sensation floated like it belonged to someone else. I released the axe handle, without looking down. I had been wearing sandals.

Jodi dashed toward me with huge eyes.

I dropped to the stump. My head hung low; I could smell the stench of armpit. Salty sweat trickled across my lips.

Jodi knelt beside me and I could feel her shaking hands against my leg.

“You’re okay. No blood. Damn it…what should I do?!” her voice quaked.

“Get the first-aid kit.”

Jodi dug through my pack. I lifted my foot and pulled the sandal off, investigating with my hands what my eyes would not.

Eventually, I gathered my courage and bandaged the wound. I went to bed determined to continue paddling the following morning, but my throbbing foot gnawed at my resolve. During the night, a lightning storm passed over us and filled the tent with steely-blue flashes of light and cracks of thunder. Rain pelted the fly. I imagined sitting in TINTIN for hours on end with an injured foot. I wanted to be courageous, but what I needed was a hospital. At daylight, Jodi ran back across the portage and retrieved her car.

Jodi Hausen

Jodi HausenJackman Clinic, Maine. As result of the axe mishap, I had to call Tom, another Outward Bound friend who was scheduled to paddle with me, and cancel our rendezvous. He could have stayed where he was, at Maine’s northernmost Outward Bound base in Greenville, but he hopped in his truck and spent hours speeding across the logging roads to help get me and TINTIN home.

By the end of the next day, following a rescue that brought Outward Bounders Tom and Dietter and their trucks to my aid, I was deposited with a stitched foot at my mother’s house, 100-plus miles to the south of the trail. Wilderness, water, and my adventure were gone, replaced with pavement, rows of homes, and the growling of a lawn mower.

My mother asked, “How soon can you get back out?”

I called my friend Tony, “What the hell are you doing home already?” he snapped.

I felt pushed and protested: Who says I have to go back?

Yet the trail had worked its way into me, and my friends and family saw the connection more clearly than I could. Then, after four days on the couch reading Against Straight Lines, Robert Perkins’s book about his canoe travels in Labrador, I couldn’t deny the tug of the trail. I longed for open water and to complete what I had started.

My mother drove me back north to meet up with Joc, my final paddling partner. I returned with a new pair of rubber boots, a hermetically sealed suture removal kit, and a dream that I would be able to keep my wound dry for the remaining 200 miles. The axe stayed home.

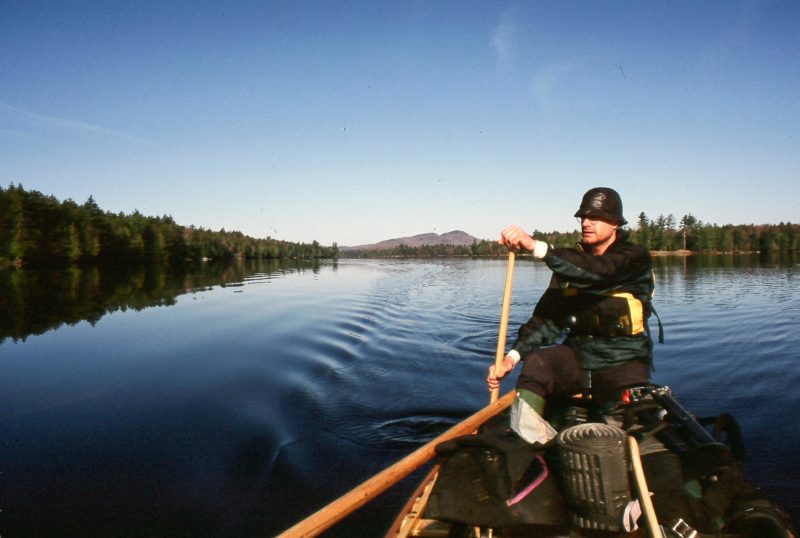

My first day back on the trail, Joc, an Outward Bound course director I’d met while working for the school in Florida, and I put in on the Moose River where I had left off the week before. Soon, we were crossing a series of remote ponds and muscling through tireless swells that licked at the gunwales. Twice, Joc’s long arms and stabilizing braces saved us from capsize. He cheered even as spray matted his blond hair, but I remained pensive, thinking about one of the rapids that lay ahead.

The Demo Bridge Rapid is a frothy Class III created by two slabs of bedrock that squeeze the river’s flow down a narrow chute 30’ long. While there are larger rapids along the trail, this was the most difficult I had contemplated paddling. The route through crosses the current far left before slipping between the slab shore and a chair-sized boulder. The rapid is made particularly gnarly by a river-wide ledge that lies just downstream of the chute.

Two years before, a brother-and-sister duo—the only other group to attempt a through-paddle of the NFCT at the time—ended their effort after a ledge on the Moose River swallowed one of their boats. I had only read about their misfortune, and assumed that the Demo Bridge Rapid was the one to derail their expedition. My Outward Bound training told me that paddling such a risky rapid during a long expedition, and in a wood-and-canvas canoe, made no sense. Yet on that day my competitive side won out.

TINTIN wobbled as Joc and I peeled out into the current. Despite having memorized the route, it’s hard for me to think straight once I’m on moving water. Amid the roiling mess, I caught a glimpse of the chair boulder.

“PADDLE!” I shouted.

The current flung us downriver.

“Damn it!” I yelled. We had to get the hell off the midstream conveyor belt. We lashed at the water and TINTIN jumped in response, enough to startle me, but where had our route gone? The slab shore loomed ahead. We were moving way too fast.

I caught sight of the chute and pried for all I was worth. Joc buried his blade into a cross draw, pulling, clawing toward the chute, and suddenly the bow snapped into the narrow opening like a compass needle finding north.

We’d done it!

Bryn Clark

Bryn ClarkMoose River, Maine. My first day back on the river Joc asked me what stories I’d tell about my experience on the trail. At the time, I didn’t think I’d have any worth telling. I felt then that I had failed because I’d left the trail. All these years later, I feel like I could tell a story about strength of spirit, will, and friendship in a myriad of ways.

We paddled across the northern bay of Moosehead Lake, the largest of Maine’s lakes, on the calmest of days. Legend about Moosehead’s oceanic potential seemed unfounded as the summer sun beat down on us. Then the West Branch of the Penobscot guided us without delay down its pine-lined corridor to the north end of Chesuncook Lake. The tucked-away Umbazooksus Stream was next, then it was on to Mud Pond. To my surprise, the murky depths along the infamous Mud Pond Carry didn’t breach my boot tops. Joc shouldered TINTIN most of the way so I could give my aching foot a break.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenMud Pond Carry, Maine. As infamous as it is old, the 2-mile-long portage had worried me for weeks. Would we get lost or stuck in the mire? Early on the trail took us through open, easygoing terrain, but nearer Mud Pond it lived up to its reputation: overgrown, obstructed by blowdown, and shin-deep in muck.

We crossed shallow Mud Pond and found a beaver dam clogging the outlet that connects the pond to the lakes of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. We bounced off the stick dam, which held back a small pond that spread through the trees. Below the dam the stream had been reduced to a mere trickle that could hardly float a toy boat, let alone our heavily laden canoe. I quickly resigned myself to another portage, but Joc jumped onto the dam and started pulling out sticks, hurling them wildly through the air.

“What are you doing?” I asked, incredulously.

“I’m not doing another damn portage,” he huffed, bent over.

“You’re crazy. Get in the boat,” I chuckled.

He spent several minutes undeterred and engaged in a Herculean task. Finally, defeated, he slumped back into the canoe, and we retraced our strokes in search of the portage trail. Later I read in David Cook’s Indian Canoe Routes of Maine (republished in 2007 as Above the Gravel Bar: The Native Canoe Routes of Maine) that the practice of disassembling beaver dams for the benefit of canoe travel was more common then I suspected. Settlers made quick work of the dams with dynamite.

We paddled back-to-back 30-mile days on the Allagash River, turning an estimated nine days of travel into just seven.

Joc Clark

Joc ClarkSt John River, Fort Kent. I spent 20 of my 55 days paddling solo, yet by the time I reached Fort Kent it was clear that my success was thanks in large part to the support of Outward Bound. The school donated food, loaned me gear, and managed my resupplies. I was steeped in the school’s emphasis on tenacity, self-reliance and personal challenge and the paddling partners who saw me through were all Outward Bound colleagues. They organized my rescue and then helped to coax me back out.

When we hit the St. John River, the last of my worries evaporated as I realized that we could float the river while barely lifting a paddle and reach the end of the trail undeterred. A day later, on June 25th, Joc and I glided quietly down the wide and shallow St. John under cloudy skies as Fort Kent, and the end of the trail, took shape on the high southern shore. Green hills poked from the Canadian side.

We were hours ahead of schedule, and still my mother was there to cheer us ashore as we ground TINTIN into the sandy beach. The elation I expected at my finale was absent. I was exhausted. Joc cinched TINTIN to the truck’s roof rack as I piled our gear in the back. My mother slipped behind the wheel to begin her second five-hour drive of the day; I slumped in the back seat. Soon, the sounds of water rippling across rock and the wind whistling through the treetops were replaced by the hum of tires on pavement and the laughter of my mother and my friend. I drifted off to sleep.![]()

Donnie Mullen is a writer and photographer who lives in Camden, Maine, with his wife Erin and their two children. For more information about his E.M. White canoe, see the sidebar in his article “Investing in Memories: Canoe Camping in Northern Maine,” in our September 2015 issue. He reviewed the Original Bug Shirt in our August 2015 issue.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Fun to read of your adventure again Donnie. Has it really been over 15 years? How is TINTIN holding up these days?

One Hellova trip, right theyah!! Congratulations to you, sir. I have often though of returning to my native Maine to do part of this trip. Wonderful read. Thanks for posting it. And many thanks to Outward Bound for all that you do.

Yup, well done there Donnie, from the wife of your first paddling partner on the trip. Maybe someday we can do the trip with the kids. Great to read about it again.

I just enjoyed reading Roy MacGregor’s book Canoe Country. One story he shares in the book is about the native practice of chopping wood on their knees. Out in the wild they cannot take the chance of an axe to the feet or legs. They consider the loss of power well worth the extra effort, as an injury will often spell death.

I love this article. It inspires me, though my own adventures are less ambitious.

Thank you for a fine story!

Wow! Very impressive accomplishment. That’s a lot of portaging. How much does the canoe weigh? Very inspiring.

So great to see this again! I am the “mom” in the story. Proud of my son today as I was when I first dropped him off at the beginning of his journey, in NY, and picked him up at the end of his journey, many days later in Maine. Such a treat to re-visit that time. Bravo, Donnie!