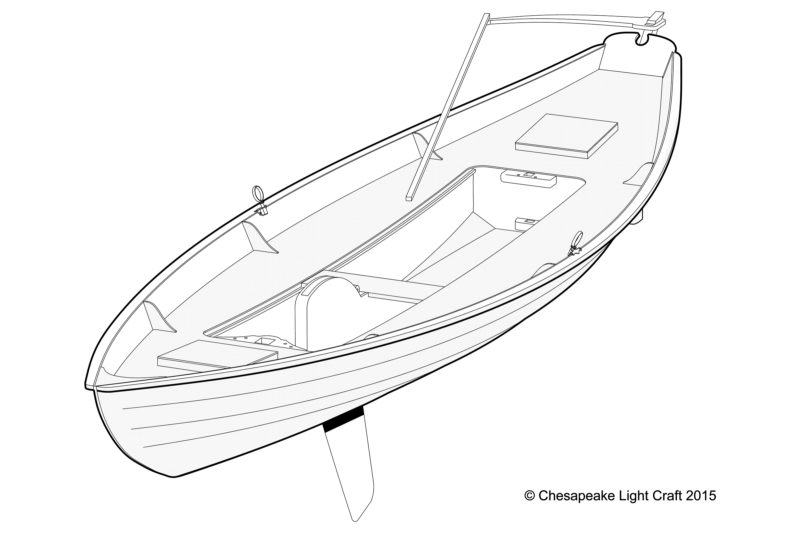

It’s unfortunate that “Jack of all trades” is so often followed by “master of none.” It is possible to do a number of things quite well, and versatility is often of more value than virtuosity. The new Southwester Dory from Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC) was designed to serve not only as a sailboat and a rowboat, but also as a motor launch, and it does well in all three capacities. Its predecessor is CLC’s Northeaster Dory, a boat that proved popular among the sail-and-oar crowd, but many prospective buyers asked about adding outboard power. Designer John Harris wisely left his Northeaster as it was and drew up a slightly larger boat that could accommodate a small motor.

The narrow, raked transom isn’t meant to support an outboard, and the slender sections aft won’t support the weight of someone at the motor’s tiller, so John situated the Southwester’s motorwell just aft of amidships. The centralized well, an optional module that can be installed at any time during or after construction of the boat, allows comfortable seating and makes it easy to get to the motor’s fuel cock, steering friction screw, tilt lock, and fuel-tank cap without having to hang overboard. It brings the motor’s noise into the middle of the boat, but in a small boat, there’s no escaping it anyway.

The well is long enough to allow the motor to kick up when it hits something or isn’t in use—a real advantage over a short well that requires removing the motor and stowing it elsewhere to transition to rowing or sailing, coming ashore, or coasting over shoals. While leaving the motor lowered creates a lot of drag, so does the motor well opening. So the Southwester has two inserts to fill the open slot, one notched to fit around the motor when it is in use, and the other to fill the entire slot. Toggles hold the plywood inserts in place.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThere’s no need to go to the trouble of installing control lines for the kick-up rudder when you can just reach over the side, ease the pressure applied by the threaded knob, and put the blade where you want it.

The rudder has a kick-up blade. A knob on the pivot bolt is backed off to drop the blade and tightened to keep it in place, up or down. Applying a moderate amount of pressure to the knob will keep the blade down and still let it swing up over an obstruction. The rudder stock is 1” higher than the skeg, and the jog will help keep lines or kelp from slipping in between the transom and the rudder. If you’re rigging the boat for sailing, keep in mind that it’s easier to tend to the rudder blade when the mizzen isn’t stepped, but even if you have to snake around the mast to get to the rudder, there’s still enough stability to keep the boat upright.

The Southwester’s Norwegian-style push-pull tiller has a half yoke extending to starboard and a pivoting extension to reach around the mizzen mast to the center of the cockpit. The transverse arm is permanently fixed to the rudder head, making the assembly an awkward thing to stow. Instead of gluing the two pieces together, I’d add a few extra layers of plywood to beef up the slot in the tiller for a secure slip-fit over the rudderhead. Having the rudder in place while rowing can work well when there’s a second person aboard to take the helm, but for rowing solo, even with a pivoting rudder blade retracted, there’s enough of the rudder in the water to cause drag, slow steering, and flop over while backing. I prefer to have it unshipped. Removing the rudder will also allow you to use the notch in the transom for sculling. The notch is deep and partially enclosed, making it also well suited for using an oar as a backup rudder.

John C. Harris

John C. HarrisThe 9’10” oars would be suitable for the beam of the dory, but a pair about 6″ shorter would fit neatly in the cockpit footwell without interfering with the seating. For those devoted to rowing, the longer oars could be accommodated by a recess built into one of the bulkheads.

Unlike CLC’s Northeaster, which has three rowing stations to accommodate one or two rowers, the Southwester has only a single rowing station. It would be difficult to fit two more stations into the Southwester for tandem rowing—the centerboard trunk and motorwell are in the way—and I’d be willing to bet that folks drawn to the boat will choose passagemaking under sail or power. A single rowing station is all that’s needed for shorter distances.

At 18′10″ x 5′2″, the Southwester dory is a lot of boat to row solo, but the stitch-and-glue construction keeps the weight down; the boat has a light and lively feel under oars and carries its way well. The 8′6″ oars I used worked well enough but were a bit on the short side; the common formula for oar length suggests 9′10″ oars would be the best fit. A foot brace could easily be attached to the motor well for rowing solo very powerfully. While the insert in the motor well eliminates drag, it’s not gasketed, so there are always a few inches of water in the well. I wasn’t even aware of it while motoring or sailing, but as I was rowing, the rhythmic surge set the water to sloshing about, and if I rowed with gusto a bit would splash into the cockpit. The water does no harm, but the meditative aspect of rowing is incompatible with all the commotion in the well. A watertight insert with a self bailer or pumping out might solve the problem. Another fix is to have something to fill the space—say, foam blocks or a custom-built insert (the one I have for the well in one of my boats has a Plexiglas window for a view below).

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe mizzen’s partners and step are built into the aft end of the motor well. Note the jigsaw-puzzle joints connecting the plywood pieces.

Balance-lug rig is used on both the main and the mizzen masts. The spars are all rectangular in section, but their tapers keep them from looking clunky. The main’s downhaul takes a turn around the mast to serve as a parrel line. It holds the boom in its proper position while sailing; when striking the main, casting off the downhaul allows the boom to slide forward, as it must as the yard rotates to horizontal and pushes the sail forward. It’s a simple and effective arrangement for a lug sail.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe storage compartments in the bow and stern provide a total of 12 cu ft of storage space.

The mizzen has a loop of line made off at the forward end of the boom and looping around the mast. It slides up and down as the sail is raised and lowered. The tail end of the mizzen sheet is tied to a bridle across the stern and its working end leads forward along the boom through a cam cleat on the mast.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamLines for raising and lowering the centerboard lead aft within easy reach of the helmsman, though the downhaul here has slipped from its fairlead/cleat.

The centerboard is lowered and held in place by a downhaul, which I prefer to a weighted board, which can’t be forced down if jammed and adds to the burden of moving the boat across a beach. The downhaul is held by a jam cleat and won’t release if the board runs into something, so a releasing cleat (by ClamCleat in the U.K.; click “Purchase Options” to find distributors worldwide) is worth having if you’re in an area of rocks or shoals—or if you’re like me and occasionally forget to raise the board before haulout.

John C. Harris

John C. HarrisWhen switching from motoring to sailing, it only takes a minute to tilt the outboard up and close the the bottom of the well. Taking another minute to stow the motor—alongside the centerboard trunk—will clear the path for the tiller across the boat when you’re coming about.

In wind around 8 knots and waves under 1′, the Southwester’s 107 sq ft of sail had me scooting along at a satisfying pace—I’d be content to sail like that for hours. When the wind picked up to around 12 knots the sailing was more exhilarating, but not approaching the need to reef. The dory tacked quickly, carrying enough momentum to not get caught in irons. With the long Norwegian push-pull tiller I could sit where my weight belonged—amidships—and the wide side benches were comfortable, with room enough to move laterally to respond to gusts and lulls. With the sails largely self tending and only two sheets to fuss with, singlehanding is easy.

The 2.3-hp outboard motor available for my test outing wasn’t the one meant for the plug in the motor well, so I had to go with the well open. The motor supplied more than enough power to get the boat moving as fast as it will comfortably go, and while there was turbulence in the well, it wasn’t enough to slosh into the cockpit. At full throttle, the raked transom pulled up quite a pile of water astern. I enjoyed not having to reach behind me to get to the throttle and shifter.

In the bow there’s a recess for stowing a long line threaded through a hole in the stem. The hole squeegees water and seaweed off and any remaining water drains through two discreet holes though the planking. The line pays out again tangle-free and can be adjusted to any length with a figure-eight on a bight. It’s a dandy system. Stowage compartments at the bow and stern are fitted with hatches for access. The side benches enclose large flotation compartments filled with slabs of expanded polystyrene foam—the pink or blue insulation panels you’ll find at home improvement stores. Ledges along the side benches support the thwart and it would be quite easy to add ledges along the well and trunk for inserts to create a continuous platform for a crew of two to sleep aboard. There’s an optional bimini top available for shade under sunny skies…which would be a good starting point for enclosing the cockpit for shelter in cold and wet conditions.

CLC has packed a lot of features into the Southwester without making it cluttered or complicated. It offers a lot of options for propulsion, and none of them feels like a compromise.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

CLC Southwester Particulars

[table]

LOA/18′10″

Beam/5′2″

Hull, stripped/200 lbs

Hull, motoring, with engine/280 lbs

Hull, sailing, rigged/350 lbs

Draft, rowing/7″

Draft, sailing/3′

[/table]

Kits and plans for the Southwester Dory are available from Chesapeake Light Craft.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Some interesting details in this boat, and some questions.

I like the rudder; I have used a big bolt into an aircraft nut for a decade now on RAN TAN, set just hard enough to keep things from coming up unless the rudder blade hits something.

I don’t understand why more people in the Norwegian tiller trade don’t do it like they do. There is a mortise in the rudder head; the yoke has a tenon that goes through the rudder head with a little wooden wedge to hold it. If the tenon is round the tiller, yoke joint can be a bolt, does not have to be a universal joint.

And the Norwegians have no problem dealing with long oars or spars. They let them stick out over the stem like a bowsprit. Things are nicely out of the way. You may want a couple of bits of line to hold things in place.

I really like the balanced lug main and mizzen. I am curious though as the CE seems to be well aft of the CLR. Does the boat produce weather helm when going to windward.

I didn’t notice a strong weather helm while I was sailing the Southwester. The rudder would appear to take some of the lateral resistance load; the longish transverse tiller may lighten the feel of any weather helm. Several of the photos taken that afternoon show the main and mizzen set parallel to one another and yet I never felt I needed to loosen the mizzen sheet to better balance the rig.

I switched to a pole-tiller to get around the mizzen mast on my outrigger canoe. After my brain wrapped around it, I would not do anything else for a small boat with skinny stern. I used two yokes, the first about 14 inches, the second about 20 inches. The longer one, per the law of levers, nicely reduces arm stress and slows the steering rate enough to let you recover from brain-glitch errors.