Any serious angler knows the need for fresh bait for a day of fishing; being able to catch your own and not having to depend on a bait-and-tackle shop is a big advantage. After many very early mornings being let down and left scrambling for bait because the bait shop was either sold out or the quality was poor, I decided it was time to make a change: I started catching my own baitfish during the week, after work, and keeping it alive in cages I sank alongside the dock. The boat I was using at the time was well suited to chasing flounder and cobia in the lower Chesapeake Bay and coastal waters off Virginia Beach, but too large for the baitfish-rich inlets and shallow coves, and I found myself looking for a small, easy-to-maintain outboard skiff.

The search for an inexpensive, used, production fiberglass skiff went on for a while without success. The fit and finish of most affordable small and simple powerboats left much to be desired. Exploring other affordable options, I discovered I could build a wooden boat for less money and put into the project the standard of finish that I wanted.

I found my way to Dudley Dix, a yacht designer living in Virginia Beach. When I sat down with him to talk about what I was looking for, he said he’d wanted to design a line of garvey-style outboard-powered boats and was looking for the right time to start the drawings. The boat I outlined for him provided the catalyst for his design project. My list of requirements for the boat were fairly basic. I had very little woodworking experience and no boatbuilding experience so I needed something easy to build, something a true novice could tackle. The project needed to go quickly enough to complete in six months, working in my spare time, so the boat could be ready for the upcoming summer. My plan was to leave the boat in a slip during the summer so I wanted it to be self-bailing, to ease the worry of swamping while the boat was tied up and unattended during the many evening thunderstorms we have here. After a few months of designing, Dudley presented me with drawings for a 16′ garvey, and I began construction.

photographs by Jesse Goodwin

photographs by Jesse GoodwinThe outwale is the only brightwork on the boat. Its wood is of unknown species, having been cut from a 2×6 that Dudley Dix found in his front yard, evidently having fallen off a garbage truck. It was once part of a door because a handle was still attached. Dudley ripped it down to size on a table saw and Kevin coated it with epoxy and finished it off with varnish.

The hull was to be built with okoume plywood and epoxy using the stitch-and-glue method. Since my boat was the prototype, there wouldn’t be a time-saving CNC-cut kit available. Instead I received a roll of full-sized patterns to transfer over to the plywood panels. The hull bottom and sides are built from four sheets of 9mm plywood using taped joints to create the lengths needed. Tabs on the five bulkheads and slots to fit them in the hull panels made stitching the basic shape of the boat together quick and easy; the bulkheads stayed securely in place while I assembled the hull.

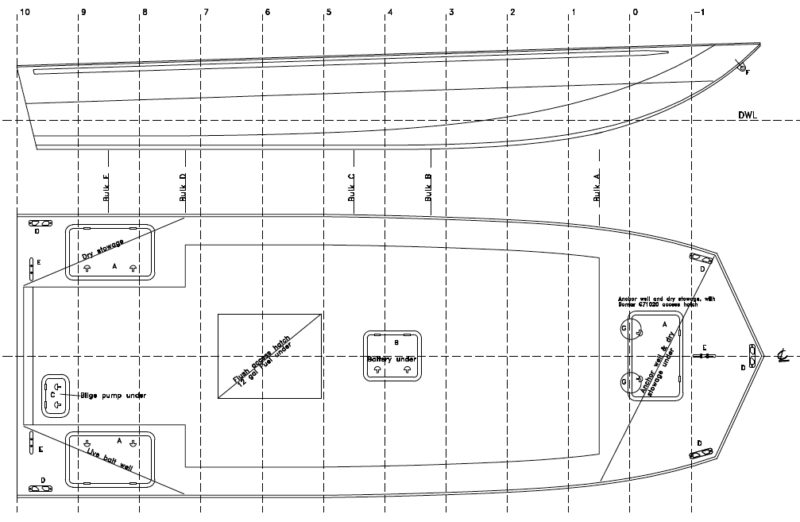

As I stitched the keel seam together, the bow took a smooth and sweeping curve upward in the simple but functional garvey fashion. Once the hull was stitched together, fiberglass tape and epoxy resin reinforced the chine and keel seams inside and out. Several layers of 9mm plywood added to the transom created a total thickness of 45mm, which is strong enough to handle an outboard of up to 50hp. Fuel-tank beds support a permanent 12-gallon below-deck fuel tank. A stout tray under the deck amidships stores the battery out of the way, keeping its weight out of the stern. A pair of 1×2 carlins running from the transom to the bow and secured in cutouts on the top portion of the bulkheads supports the inside edge of the deck.

The framework for the bilge-access hatches was laid out according to the full-sized patterns, and the cockpit sole was cut to fit. Before the sole was installed, its underside and the entire bilge area were coated with three coats of low-viscosity epoxy. To save money and enhance the clean appearance of the deck, I built my own flush-mount hatches and access covers.

Dudley and I decided against covering the hull with a layer of fiberglass and instead three coats of epoxy seal the entire hull. The extra time and work needed to obtain a nice finish over the weave of fiberglass cloth did not justify the extra abrasive resistance a layer of ’glass would have provided, given the way I’d be using this boat: I had no need to pull it ashore.

To stiffen the hull and add longitudinal strength, 1×2 stringers were added to the bottom. Installed on the exterior side, the stringers would help give the boat lift by trapping water and air while on plane and add some protection if I should happen to run aground in the shallows. All of the 1x2s I used for the hull and carlins were sourced from our local home improvement center, helping keep the costs down. It was cheaper than shopping at a specialty lumber yard but I had to spend lot of time picking through the select poplar boards looking for pieces that would suit my needs.

The interior is quite open to keep the boat versatile. Sealed storage under hatches in the foredeck, sole, and the seat to port keeps gear out from underfoot. The starboard seat conceals a live-bait well.

Once the hull was built, sealed, and faired, I could fit the deck. To make the boat simple to maintain and keep the cockpit open, the only interior furnishings are a pair of rectangular boxes built into both sides of the stern. The starboard one is a 19-gallon bait well with plumbing to support a 500-gallon-per-hour pump to keep baitfish alive and happy. The port-side compartment has a dry storage box that also serves as a seat for the helmsman. The forward section of the port compartment has an electronics panel that is easy to access and see while steering from the seat flush with it.

The instrument panel includes switches for lights and bilge and bait-well pumps, flush-mount GPS/fishfinder, CD player with AM/FM radio, master electrical switch, and fuel gauge.

Side decks, 7″ wide, extend from the stern boxes forward to the foredeck, and along these decks are flush-mounted stainless-steel rod holders, three per side. A hatch on the foredeck provides access to a storage compartment. The enclosed compartments leave plenty of space in the cockpit for stowing all of the safety equipment, fishing gear, and anchor.

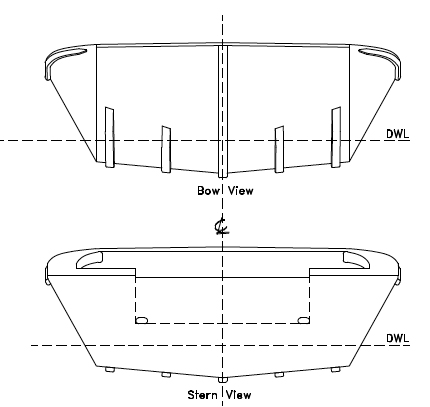

I named my boat INLET RUNNER, and Dudley adopted the name for the design. On the water, the boat jumps up on plane with little rising of the bow, and then quickly levels out at speed. With a dry hull weight of only around 400 lbs, she feels very light and responsive. Banking into turns, she carves around nicely and feels predictable. With two adults on board, the 25-hp, four-stroke outboard pushes her in the mid 20-knot range at full throttle. At three-quarters throttle, she cruises along nicely around 19 knots. She’s at her best running trim with a passenger just forward of the centerline with the helmsman sitting close to the stern. The hull has an 18-degree deadrise at the entry, which helps soften the ride in a chop; this angle flattens to 5 degrees at the transom. At rest she draws just 4″ and, for having only a 6′ beam, she provides a very stable fishing platform and has enough buoyancy for standing on the side while pulling pots.

The self-bailing cockpit has plenty of height to drain well and to keep the scuppers from taking on water while moving in reverse and at anchor in choppy conditions. Seat cushions made to snap on top of ice chests add comfort to the tops of both stern compartments while under power. The open cockpit layout leaves plenty of room for crab pots if needed or a small cooler added for extra seating.

Running in a slight chop on Virginia’s Back River, the builder’s home waters, INLET RUNNER moves along nicely with very minimal pounding.

The Inlet Runner’s lightweight design needs minimal horsepower to perform well. We can cruise around all day on only a few gallons of gasoline, making the garvey very inexpensive to operate. With every nook and cranny sealed with epoxy, maintenance is easy. After returning to the dock, a quick rinse with fresh water is all that is needed. I leave the boat at the dock uncovered and it is unaffected by downpours.

The Inlet Runner is a great all-around, well-thought-out and -designed little powerboat. It’s easy to build and once completed is a lot of boat for the money: around $3,000 for the completed boat, less the engine. From start to finish the boat took a little over six months to build. I expect to spend many pleasant hours on her catching baitfish, fishing for flounder on calm days, and just messing about in the local estuaries and protected waters.![]()

Kevin Agee is a professional BMW Mechanic living on the east coast of Virginia. He spends most of his spare time fishing or sightseeing on his local waters. He has long been passionate about small, simple, and easy-to-maintain wooden boats that are versatile and have character; new to boatbuilding, he’s looking forward to more projects in the future.

Inlet Runner Particulars

[table]

LOA/15′11″

Beam/5′11″

Draft/7.5″

Design displacement/1,180 lbs

Recommended outboard engine/25–30 hp

[/table]

Plans are available from Dudley Dix Yacht Design and can be purchased along with measurements for the components or full-sized patterns on paper or on Mylar. A pre-cut plywood kit is in the works.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I’m curious how the self-draining cockpit works. Do you have a picture of the scuppers?

The cockpit sole slopes downward to the stern and water drains through two holes in the transom; the sole and the scuppers are above the waterline. You can see the starboard scupper in the enlargement here and if you take a close look at the photo showing the boat on the lawn, you’ll see the port scupper to the left of the motor.

Christopher Cunningham, Editor, Small Boats Monthly

Congratulations to Kevin on his construction and to Dudley Dix for his design. For a first-time builder, Kevin did a great job. May the winds be at his back and smooth seas ahead.

I’m very proud of my younger brother Kevin. As an avid outdoorsman myself, I appreciate the “need bait” excuse to build an awesome boat! Probably one of the better looking bait boats I’ve seen.