John Hartmann

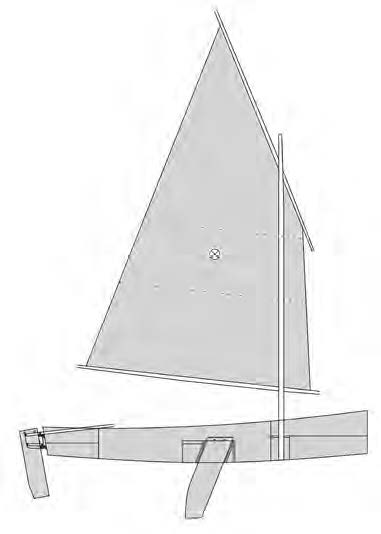

John HartmannThough Michael Storer’s plans call for a single balance-lug sail, boatbuilder Clint Chase added a mizzen to better keep the boat headed into the wind when reefing the main.

Twenty years ago, Australian designer Michael Storer drew up the Goat Island Skiff, which he named for an island in Sydney Harbour. Steeped in the Australian design and DIY traditions, he intended it to be light, fast, and easy to build. It was a successful idea, as to date around a thousand skiffs have been built in 27 countries. Over the course of two decades, the plans have evolved into a detailed how-to-build book, and it is now possible to get the Goat Island Skiff (GIS) in kits.

In Australia, dinghy weight standards are 8–10 lbs per foot of length—much lighter than the European and American standards set in the 1960s by relatively heavy fiberglass boats. A GIS, at 130 lbs, is about half the weight of a Finn dinghy (designed in 1949), but it has the same sail area. It is about the same weight as a Laser (designed in 1970), but with 25 sq ft more sail. Its 5′ beam gives a singlehander more power to carry that sail, but unlike a Finn or a Laser, the GIS can t ake a family sailing. The flat-bottomed skiff shape is relatively skinny on the water line, and with its significant sail area and light weight it can ghost nicely—much better than one would expect of a relatively high-wetted-surface hull.

A balance lugger, the GIS has some tweaks to make the sail set efficiently. The specifications call for the mast to be as unbending as possible, which is critical to a well-setting luff. A powerful downhaul controls draft. In some boats, this control has been moved aft to work as a vang as well, with a line around the boom and mast; this so-called “bleater” keeps the boom from going forward.

Storer recognizes that the skiff shape may not be the best for rowing, and he states that 9′ oars are needed to make a 5′ beam boat work under oars. The oars will fit in the boat’s bottom, or can be stored on the top of the bow tank, blades at the stem, handles held by the ’mid-ship seat knee.

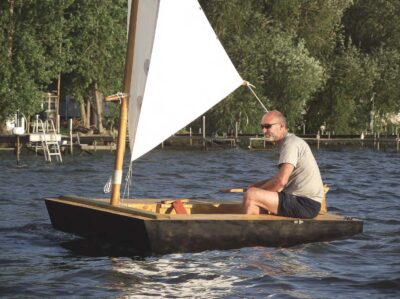

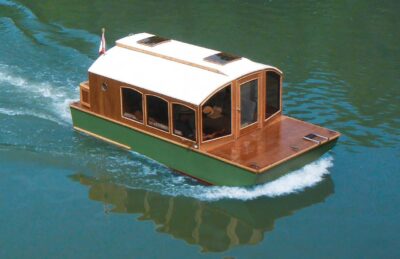

Despite having heard of the Goat Island Skiff for years, I’d never sailed one until last summer, when I encountered two at the Small Reach Regatta in August; one of those boats was owned by amateur builder Paul Hayslett of Branford, Connecticut, and the other by Clint Chase, a professional from Biddeford, Maine. There was also a former GIS owner, Christophe Matson, from Bow, New Hampshire, on hand; he’d had his boat for four seasons before moving to a camp-cruiser he could sleep aboard.

Paul and Cristophe are experienced sailors who were looking for an inexpensive, yet sophisticated, boat to satisfy their skill levels. Both were first-time builders, but it doesn’t take much to build a Goat Island Skiff. The plans come with detailed instructions, and the materials amount to, essentially, six sheets of 6mm plywood.

Storer’s website goes way beyond the usual designer’s offering, providing information about boat tuning and links to other online resources including Facebook pages, blogs, and sites maintained by builders and sailors. Storer also monitors his own Goat Island Skiff Facebook page as well as the WoodenBoat Forum (forum.woodenboat.com), and responds fully to email questions.

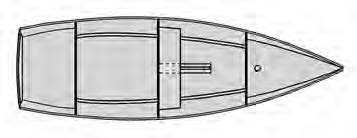

The builder assembles the sides, bottom, and transom to complete the basic hull. Three seats and their supporting bulkheads form the internal skeleton for the hull structure and built-in flotation tanks. Everything is coated with epoxy; no cloth is needed. Skids provide bottom protection for beaching. The daggerboard, breasthook, quarter knees, and rails finish the boat. This minimal list of parts keeps the hull light. And that’s the impression I got when I stepped aboard Clint’s boat, BLEAT, for the first time: Everything seemed light.

Clint Chase

Clint ChaseThe Goat Island Skiff has a clean uncluttered interior, with flotation and storage compartments under the bow and stern thwarts.

To get the boat underway from the beach, a long, well-shaped daggerboard and rudder need to be shoved down once the water is deep enough. The rudder is unusual; it’s an extremely efficient vertical blade with an ingenious kick-up system. The balance lugsail goes up easily, and the powerful downhaul working against a stiff, light, hollow mast lets you control the draft. Clint and many other GIS owners are rebuilding their booms to take the loads of a loose-footed sail, a sail that will set better than one laced on. The wind was light on the day of my trial: 5–8 knots with a small chop.

Going to windward, the boat accelerated quickly in the puffs—puffs that were strong enough for me to sit on the rail with a foot hooked into a convenient spot that Clint built into his center thwart. Skiff owners usually have a Y-shaped toe strap, or a pair of hiking straps, which Clint will be fitting into his boat. A tiller extension is essential; Clint made one with a bit of string coming out of a hole in the end for a truly universal joint. If sitting on the bottom or a side seat and not moving around much is your sailing style, you would be better served by a heavier boat. Fore-and-aft positioning wanted me to be on the rail or sitting on the seat amidships. The feel of the helm was very light, with just a hint of a tug to weather.

Clint added a small mizzen to make it easier to lie quietly to the wind while reefing or moving about the boat. I played with fore-and-aft trim and the amount of heel needed to work into the light breeze. Flat-bottomed boats tend to slap as the waves hit the windward chine. Most of that effect is removed when the boat is trimmed with the bow down.

The boat tacked easily. A bit of a roll, something common in dinghy sailing, helped speed her through it in the light stuff. I could just drop the tiller to leeward, hesitate a beat or two as she swung up and through the wind, and then switch tiller and sheet hands and move to windward.

In light conditions, sailing off the wind was simple. The wind was so light that I didn’t bother retrimming the mizzen. Jibing was a non-event: Simply steer to leeward and give the sheet a yank. As the boom came over, a small S-turn to the new leeward side countered any tendency to round up. The big efficient rudder helps. When sailing downwind I found, like on a Laser or most other modern dinghies, a bit of heel to windward made steering with the rudder superfluous. Upwind in light air, steering by heeling a bit to point up and flattening out to head off also worked well.

In discussing capsizing, Paul noted that building a boat yourself gives one the confidence to fi x things. He’d gone over on a gusty day and righted the boat, but was too close to a lee shore to climb in with the sea that was running. In hitting the beach he put a couple of cracks in the bottom. Once the boat was bailed out, he sailed home, looked at the cracks, looked at the season to come, put some duct tape on them, and went sailing. Permanent repair waited until the off-season.

The fact is that any light boat can be capsized. The Goat Island Skiff has pretty high sides, which make it harder, but it can be done. She is easily righted with the daggerboard floating pretty close to the water and the hollow mast keeping her from turtling. Righted, she floats with the daggerboard trunk out of the water. Getting back in can require some agility. If I had problems I might rig a step that could drop into the water off the transom the way it’s done in sea kayaks. With the boat drifting sideways, a yank on the mainsheet could balance pushing down on the weather side, a common practice in other singlehanded dinghies.

Paul was rowing while we discussed his experience, while I was paddling my kayak alongside. His crew was sitting on the bottom of his skiff just ahead of the stern seat. The trim for rowing was perfect; I could just see the edge-grain in his plywood bottom with virtually no transom drag. I also watched Clint and his crew rowing. He was more heavily loaded with his full camping kit, and might have been dragging ½” of transom.

What is really unusual for such a relatively high-performance boat is that you can take a family for a sail. With a crew of two or more, the skiff settles right down. On the long broad reach home on day two of the Small Reach Regatta, the wind had come up to white-caps and a number of boats reefed. Clint didn’t reef, although he has a well-organized jiffy reef for his first reef. His passenger simply rode the center seat, facing forward, and Clint sat on the rail. With puffs, he was well positioned to hike out a little and his passenger could slide up or down to keep the boat level. Later, when BLEAT sailed to the ramp for haulout, Clint’s passenger was comfortably sitting on the bottom ahead of the center thwart reading and handing out cookies.

It’s hard to imagine a more versatile small sailing boat. Her performance in racing against modern dinghies is impressive, with handicap numbers like a Laser radial or OK dinghy. But you can also sail sedately, taking along friends. While rowing is not the boat’s strong suit, it is acceptable and the GIS can even take a small outboard. If I were not over-boated already (by some standards), I’d think about adding one to the fleet.

Plans for the Goat Island Skiff are available at https://www.storerboatplans.com/boatplans/goat-island-skiff-simple-sailing-boat-excellent-performance-lightweight. You can see pictures and contact other builders at www.facebook.com/groups/GoatIslandSkiff. Kits are available from Clint Chase at https://www.chase-small-craft.com/.

Particulars

Length 15′ 6″ (4.73m)

Beam 5′ (1.52m)

Hull weight 128 lbs (57kg)

Sail area 105 sq ft

(9.75 sq meters)

More than 1,000 Goat Island Skiffs have been built since

Michael Storer first drew the plans 20 years ago.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.