Jim Levang’s Calendar Islands Yawl is a real beauty. Maine designer Clint Chase acknowledges the influence of designers he admires, especially in his early work—Paul Gartside, Iain Oughtred, François Vivier, and Joel White in particular—but intuition also plays a big role in his boats. “I just draw until it looks right,” he says. Based on this new yawl of his, it’s an approach that works extremely well, if you have as good an eye as Clint Chase, and have spent as much time looking at boats as he clearly has.

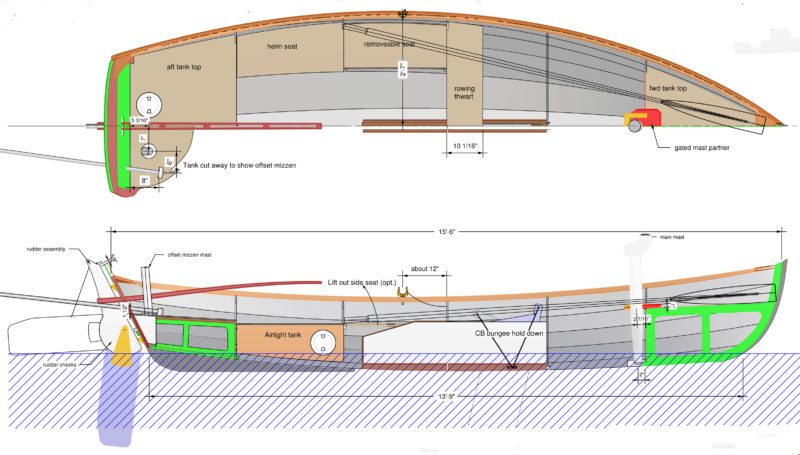

One design that Chase spent some time looking at was Australian designer Michael Storer’s Goat Island Skiff, a seemingly simple flat-bottomed skiff with a big balance-lug rig that has earned a reputation as a very fast sailer. But the Goat Island Skiff is not at its best in a chop, or under oars. One of Chase’s friends suggested there ought to be a Maine version of the Goat Island Skiff, something that could handle the rough waters and open stretches of the Maine coast. Chase happened to have on hand the preliminary 3D models for an 18′8″ yawl he’d been working on. It was too beamy for easy rowing, and much bigger than the Goat Island Skiff, but with his friend’s comments in mind, he played around with the design and, after scaling it down to 15′6″ and a beam of 5′2″, everything seemed to fit. The Calendar Islands Yawl was born. Chase describes the new design as “a fast, mostly-sailboat for singlehanders who would need to row for good lengths of time.”

Just two weeks after receiving the very first kit for a Calendar Islands Yawl, builder Levang started planking, and just three weeks of evenings and weekends later, working alone in his garage, he had a fully planked hull. Considering all the preparation work necessary for a conventional build—lofting, molds, strongback, keel, stems, and transom—I can see why Levang reported that the boat almost built itself.

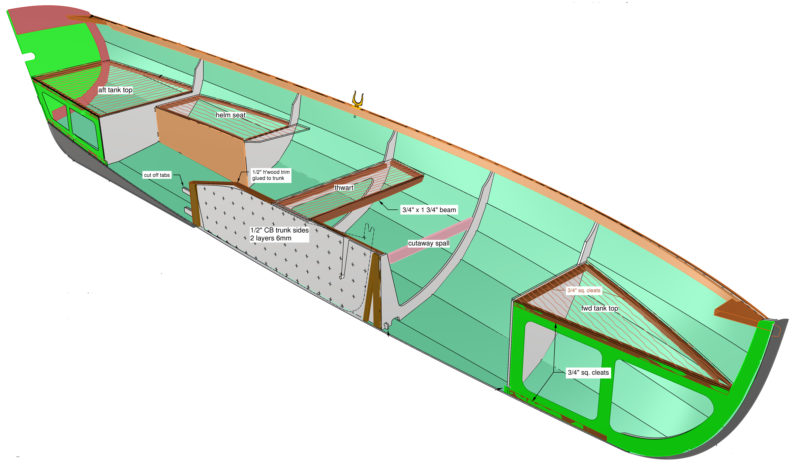

The kit’s well-designed building jig, computer-cut in oriented-strand board, speeds construction considerably. Its molds are cut to fit the boat’s permanent frames, and tabs and slots routed into adjoining parts make them self-locating. “It’s a very slick system,” says Levang. Frames, bulkheads, and the centerboard trunk are positioned, epoxied, and filleted before the planking goes on, so much of the interior is already in place once the boat is turned right-side up, eliminating a lot of fussy fitting and fairing.

Jim Levang

Jim LevangThe CNC-cut joints in the long plywood panels are cut with three levels. The middle level is designed to lock the pieces together. The outer levels have an undulating curve that avoids the weakness of a straight butted edge and offers a more pleasing appearance than a jigsaw joint.

The 15′6″ Calendar Islands Yawl is designed for glued-lapstrake construction, with a narrow flat bottom and five strakes. The planks come precut in sections, ready for assembly into full-length strakes. The jigsaw-puzzle joints that join the sections together, commonly left exposed in kit boats, is invisible, cut only in the middle laminates of the plywood and overlapped by the outer laminates. With this stair-stepped approach the resulting seams visible on the inside and outside faces of the planks are gently undulating lines, a more refined look for a bright finish than the bulbous curves required to lock sections together . The bottom is glued to the interior framework and then the garboards are hung; seams between the bottom and garboards are reinforced with fiberglass tape. Before the remaining strakes are added, the garboards and bottom are sheathed entirely with fiberglass cloth and epoxy.

The kit includes precut parts for every plywood component in the boat, a detailed bill of materials, and a few full-sized Mylar patterns for parts that aren’t precut. Builders have the option to purchase an epoxy-fiberglass kit, a hardware kit, a sail, a painting kit, and even a carbon-fiber mast.

“All of my boats will eventually be buildable from plans or kits,” Chase explains, “but I need to convince people that the kits make more sense. It’s a huge added value to have all of the parts precut.” CNC-machine-cutting the parts can save on the cost of materials, notes Chase, because it can cut a tighter-nested sheet layout than it’s possible to do by hand, and removes the possibility of cutting errors. In addition, a typical kit customer will see a 25-percent savings in the time required to finish the project. “That said, when I was getting into boatbuilding,” Chase says, “I was frustrated when a boat was only available as a kit. I wanted to learn more about lofting and making plank patterns and so on. I respect that, which is why I want to offer plans as well.” There are a lot of traditional skills to learn and put into practice when you start with a lines drawing and a table of offsets: With a precut kit you skip lofting, fairing lines, and picking up patterns.

Jim Levang wasn’t bothered by that. To him, a computer-cut kit is not a shortcut; it’s merely the direct route, the logical outcome of the high-tech design approach Chase employs. Using paper plans to build a boat designed in a digital 3-D modeling space for plywood construction, Levang says, “would be like hooking horses up to a car and using it as if it were a stagecoach.”

Jim Levang

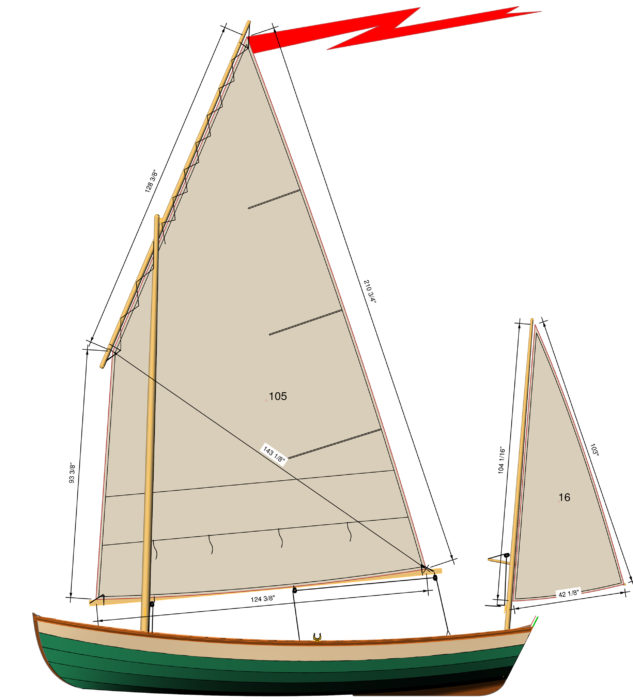

Jim LevangThe 105 sq ft main and the 16 sq ft mizzen offer good speed in light air. The 14’11” mast and the 11′ boom are both hollow with birdsmouth and box construction respectively.

I had Jim Levang’s Calendar Islands Yawl —hull No. 1—to myself for a 10-mile sail across the western tip of Lake Superior near Duluth. Rigging and launching the yawl was a cinch: We stepped the masts, pinned the removable boomkin in place, attached the rudder and tiller, and backed the trailer into the water until the boat floated free. I hoisted the balance-lug mainsail with the first reef tied in and shoved off from the dock.

I hadn’t gone more than a half mile before I decided to shake the reef out and try the yawl under full sail. With the mizzen sheeted in, the boat lay sedately head-to-wind, drifting slowly backward as I dropped the mainsail. Undoing the reef and rehoisting the sail took only a minute or two, but by that time there was a 700′ ore boat inbound through the ship channel. I tacked and jibed in tight circles to stay well out of the way, dodging back and forth in the narrow space between the nearby loading docks. The Calendar Islands Yawl came about reliably and smoothly, even in the shifting breezes behind the tall ore docks. Everything felt good and as soon as the channel was clear, I headed out onto Lake Superior.

By the time I’d reached Duluth’s inner harbor early that evening, I’d had a fair chance to try out the new design. The big, high-peaked mainsail is a delight in light airs, moving the boat along at a steady 3 knots when I can barely feel the breeze. The leg-o’-mutton mizzen is self-tending and almost makes the boat maneuverable enough for parallel parking.

Sailing performance is clearly the main focus of the design, but even so, the boat feels light and responsive under oars, tracking and steering well. Unstepped, the mast fit easily in the boat (heel aft, masthead protruding over the bow) without obstructing the oarsman’s stroke. The trim seemed just right for a singlehander, with the transom carried well out of the water. I maintained 2 knots without much exertion at all. With my long arms I felt the spacing between the oarlocks and the thwart was a bit too short, though; a wider thwart that extends farther forward would allow some room to accommodate rowers of different heights or to change position slightly during long stretches at the oars. There’s more freeboard than I’m accustomed to in a rowing-oriented boat, but that’s not a complaint; with 121 sq ft of sail, that extra freeboard will be greatly appreciated when sailing in rough conditions.

The late afternoon brought stronger winds, and I was soon sitting on the rail and paying close attention to the gusts. Even under full sail the boat felt stable and well under control, but like the Goat Island Skiff, it carries a big rig for such a light boat, allowing stellar performance in light air and keeping things manageable when it breezes up. Still, “reef early and often” will be the general rule. The yawl rig lets the skipper heave-to easily for reefing, or bringing instant calm and comfort whenever a break is needed. Sailed sensibly, this is a boat that can take you places—and more important, bring you back.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinThe bottom panel and the garboards are butted rather than lapped to provide a more abrasion-resistant bottom for beaching.

Large sealed chambers in the bow and stern, and under the side benches, provide ample flotation for capsize recovery. The tops of the bow compartment and center thwart are on the same plane, well below the sheer, providing a handy, unobstructed space to drop the mainsail and stow the bundled sail, boom, and yard. The tiller passes through an oval hole in the center of the transom; the mizzen is offset to starboard so it’s not in the way. The combination of a long tiller and a long centerboard trunk made onboard maneuvers a little awkward, though—a shorter tiller with an extension would be much more convenient.

The Calendar Islands Yawl has both a centerboard and a daggerboard option. The centerboard has some nice features: The interior sides of the trunk have shallow grooves to receive the board’s pivot pin, and these grooves make it possible to insert and remove the centerboard through the top of the trunk. The board is held down with a simple bungee, allowing it to retract if it hits an obstruction. Although I generally prefer centerboards, I’d make an exception in this case. With the boom kept fairly low to maintain a low center of effort for the rig, getting around and over the centerboard case when coming about felt more than a bit clumsy, even after a few hours aboard. A daggerboard would open up the cockpit aft of the center thwart completely, making it much easier for the helmsman to move across the boat.

Then, too, during my sailing trials I sometimes found myself sitting farther back in the boat than good trim demanded, at the forward edge of the side seats rather than nestled in behind the rowing thwart. The space between the side benches and the center thwart, an interesting design feature, creates a cozy spot well forward for the helmsman to lean against the side of the hull when a bit of weight is required to windward. A removable seat insert can be used to extend the side benches to the thwart when desired, but either way, a daggerboard would be a better choice here, since the centerboard case restricts the space available.

Jim Levang

Jim LevangThe 10′ oars called for in the plans get tucked between the inside face of the stem and the top of the fourth frame aft to keep them out of the way when under sail.

By the time I reached the Duluth ship channel and dropped the main to row into the inner harbor, I was wishing I could have more time with the boat. A whole summer, maybe with time to adjust the details of rigging and fitting out for camp-cruising, time to find out just how much speed that big rig can really provide, and time to get used to the admiring comments from other sailors as we breeze past them—although I must admit that, after my day with the boat, I’d already grown accustomed to that part.

Tom Pamperin

Tom PamperinFour separate watertight compartments provide flotation and , through watertight deck plates, dry storage for gear.

The Calendar Islands Yawl is so beautiful, and meets its design brief so well, that I had to remind myself that the boat I’ve sailed is the first of its kind, rather than an established design that has gone through a number of small refinements over the course of several years. Chase is considering minor changes, including a slightly firmer turn of the bilge, and a lower transom to increase bearing aft and provide a little more speed off the wind. He also intends to remove the aft compartment and extend the side seats back to the transom, which would simplify construction of the mizzen step while still providing plenty of buoyancy. And although Chase hadn’t initially intended the crew to sleep aboard when cruising, he may include details for an optional sleeping platform. But whatever tweaks Chase incorporates, his Calendar Islands Yawl has already hit the mark.

I’d had a great day of sailing, but it couldn’t last forever. As the sun dropped below the horizon, Jim Levang met me at a small beach along Duluth’s inner harbor, where the boat’s rocker and narrow flat bottom made it easy to roll the hull up onto a couple of plastic fenders. From there, four of us lifted the boat out and carried it to his trailer. A few minutes later we were on the road.

As Levang dropped me at my car back on the Wisconsin side, I was already running through my list of fellow boatbuilders. I have two boats already, and a new build underway, so I’m not in the market for another boat yet, unfortunately, but there’s got to be someone in my area who can be persuaded to build a Calendar Islands Yawl—the daggerboard version. It’ll have to be someone who’s too busy to go sailing much himself and willing to loan the boat to me.![]()

Tom Pamperin (www.tompamperin.com) writes regularly for Small Boats Monthly. His first book, JAGULAR Goes Everywhere: (mis)Adventures in a $300 Sailboat, was released in 2014.

Calendar Islands Yawl Particulars

[table]

LOA/15′6″

Beam/5′2″

Depth amidships/22″

Estimated hull weight/~175 lbs

Displacement/~520 lbs

Sail area, main/105 sq ft

Sail area, mizzen/16 sq ft

[/table]

Kits (from $2,537.50 to $5205.00) and plans ($250) for the Calendar Islands Yawl are available from Chase Small Craft.

Builder Jim Levang has a few more videos of sailing STELLA MARIS on his YouTube channel.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I am somewhat enamored with the America Skiff 20 and the Redwing 21, but this is an intriguing design in a smaller boat. So many boats, so little time. I just built my first, a Jimmy Skiff from Chesapeake Light Craft. I still have to add the sailing rigging and learn to sail.

Any information available on costs for plans and/or kits? Given my location, probably plans.

Robert, with the cutting of parts being done on both coasts, I can send kits anywhere in the US. The Calendar Islands Yawl is getting a revamp based on what I’ve learned from the first-built CIY, Hull #1, written about here. Getting that revamp into production is dependent on getting some preorders, so if you are interested, give me a shout at 207-602-9587 or email me at [email protected]