Much like Nesbitt sodas and Odell Hair Trainer products, Lyman powerboats were everywhere in the 1950s. Thousands of consumer products were sold, used, admired, and then, eventually, cast aside. Tastes and styles changed, and that was pretty much that. Moreover, because they were all so common, nobody paid much attention to any of them, and—with the Lymans as one exception—nobody is much interested in bringing them back into modern use.

Fortunately, though, some people do care about the classic lines and good basic construction of the Lyman Boat Works’ line of powerboats, which included everything from small, zippy runabouts to family cruisers up to 35′ or so. And, as is the case with the 1950s cars of big fender fins, hood scoops, and lots of American-made steel, Lymans are still worth having for both their iconic status and for what they can still do in the environment for which they were designed. So that’s where Jonathan Taggart and Anne Witty started some 10 years ago when they began looking for a salvageable Lyman runabout for use in their waters of Georgetown, Maine.

“I was particularly interested in a clinker-built boat, one small enough for an outboard,” Taggart recalls. Several runabout brands from the ’50s combined lapstrake, or “clinker,” construction techniques with marine plywood and highly durable caulking concoctions, resulting in reliably watertight boats. “It didn’t really have to be a Lyman,” Taggart says, noting Penn Yan as just one other example of a company that produced clinker-built outboard runabouts with a rock-solid combination of plywood and caulking. But Lyman lapstrakes were what Witty and Taggart were most familiar with. “Plus I wanted a boat that chuckles,” says Witty, describing the trademark sound of small wavelets bouncing off the hull of a lapstrake boat.

Living in Maine, they began their search and quickly ran into a problem. Taggart quotes a veteran Lyman restorer as saying, “Don’t even bother looking in the Northeast. The ones worth having are so overpriced you can’t afford them. And the rest aren’t worth having at any price.” Taggart and Witty soon found this counsel painfully accurate—so they cast their nets ever wider.

Jonathan Taggart

Jonathan TaggartWith a no-frills functional layout, the runabout is easy to handle and to care for.

“Not surprisingly, we started finding more Lymans available in the Midwest,” says Witty. The birthplace of all Lymans was Sandusky, Ohio, a small city on the shores of Lake Erie noted for its recreational uses of that ideal location. With such a prime piece of real estate at hand, the brothers Bernard and Herman Lyman began a small boatbuilding business in the 1870s. Starting in Cleveland, the company eventually moved to Sandusky, where it grew on a reputation of using the best materials—white-oak keels and frames, white-cedar planking (plywood planking came later), nonferrous fastenings—while employing craftsmen who didn’t mind slowing the production line down a bit to get a fit or finish just right. From the start, Midwesterners gravitated to this type of proven, durable product in droves, while East Coast customers caught on later in the 20th century.

Eventually, Taggart and Witty found their 161/2′ runabout in a barn in Charlevoix, Michigan—although the “find” was actually in the modern sense of finding an item via relentless Internet searches. “I didn’t mind buying it sight-unseen,” says Taggart, who telephoned the owner and was told about all of the 1958 runabout’s deficiencies, which included rot in the stem and part of the keel, as well as general neglect from sitting in a barn for years. Returning overland from a business trip to Oregon and Montana, Taggart “swung by” Michigan’s Lower Peninsula on his way back to Maine. Finding the boat as described, including a trailer for the trip home, he paid the $2,000 and set to work.

From the beginning, we knew this wasn’t going to be a restoration to museum standards,” says Witty, who has spent much of her adult life as a museum curator—as has Taggart, a fine arts conservator. “We looked at it (the boat) as history, telling the story of its owners and its uses over time. We said, ‘Now we’re going to be part of its history, too.’”

So the curators began a non-curatorial process that started with repairing the stem and keel. “It was surprisingly easy,” Taggart says. The rot only extended into the false stem and false keel. The rest of the true backbone of the boat was still as sound as a 1958 silver dollar. Even better, the resorcinol glue in the laps in between planks was still solid, which isn’t always the case with Lymans. Hard use over many years sometimes rattles that glue free, and the bronze nails at the overlapping planks can’t fully compensate. Many elderly Lymans lack reliably watertight planks at every launching. But with Taggart’s Lyman, the planking was still very tight. So far, so good.

Being a boat built for an outboard, however, it was tough to tell exactly what size engine would be appropriate for a low-riding vessel with pronounced tumblehome aft. Weight would clearly be an issue, as it was in 1958. The boat itself is only 650 lbs dry weight and has room for four passengers. The U.S. Coast Guard ratings for such a boat have long been lost, but it seemed to Taggart that an engine much over 150 lbs might push the top of the boat’s transom perilously close to the waterline, especially when someone stood aft. In 1958, that meant you might be limited to an engine only up to the 25-hp range—older outboards generally having a higher weight-to-horsepower ratio than modern outboards. Additionally, Taggart and Witty wanted a quieter, more fuel-efficient solution provided by a modern four-stroke outboard—with some added get-up-and-go to it.

Settling on a 223-lb, 50-hp Honda outboard meant Taggart had to raise the transom’s upper edge by about 3″. “They still make that stain,” Taggart the conservator says, pointing at the nearly-invisible line where the top of the original mahogany transom meets the new filler piece. The stain to which he was referring comes from Sandusky Paint Co. (www.sanpaco.com), the Ohio-based company that has been supplying Lyman owners with specialty paints and stains since 1927. Taggart also stuck with the color known as “Lyman Sand Tan” for floorboards and other assorted pieces.

Jonathan Taggart

Jonathan TaggartSmall enough to reside on its trailer, and with plywood lapstrake planking that doesn’t need to “take up” after launching, this Lyman allows its owners to access their sailboat’s mooring regularly from a public boat launch.

But that’s about where the curatorial inclinations ended. “We’ve been concentrating on protection, not perfection,” Taggart says of his other paint and varnish efforts, which might earn him a B-minus at Varnish University. “We bought the boat intending to use it, to bang around in it, run it up on the beach, that sort of thing,” he says, adding, “you know: much like the original owners of Lymans.”

To that end, Witty and Taggart agreed to change the original Lyman cable-and-pulley steering system ransom’s upper edge by about 3″. “They still make that stain,” Taggart the conservator says, pointing at the nearly-invisible line where the top of the original mahogany transom meets the new filler piece. The stain to which he was referring comes from Sandusky Paint Co. (www.sanpaco.com), the Ohio-based company that has been supplying Lyman owners with specialty paints and stains since 1927. Taggart also stuck with the color known as “Lyman Sand Tan” for floorboards and other assorted pieces.

But that’s about where the curatorial inclinations ended. “We’ve been concentrating on protection, not perfection,” Taggart says of his other paint and varnish efforts, which might earn him a B-minus at Varnish University. “We bought the boat intending to use it, to bang around in it, run it up on the beach, that sort of thing,” he says, adding, “you know: much like the original owners of Lymans.” To that end, Witty and Taggart agreed to change the original Lyman cable-and-pulley steering system.

Jonathan Taggart

Jonathan TaggartThe current owner modified this boat’s transom, raising it and neatly matching the original finish, to accommodate a quiet and efficient four-stroke outboard.

And speed and reliability is what we got when we took little DEIOPEA, named for one of the Nereids of Greek mythology, out for a spin. Even after weeks in the owners’ barn on a trailer, the boat didn’t leak a drop as it hit the water and floated free of its trailer. Better still, with three adults aboard, the boat quickly got up on plane, roughly at half of the top-end rpms. Proper adjustment of the trim took a little time to figure out, but that’s common on any runabout, modern or otherwise.

Running at about 25 to 30 knots, the boat responded well in the smooth waters of our testing cove in Georgetown, Maine. In tight turns, her stern skidded a bit but didn’t feel too squirrelly. Taggart says he has considered installing skegs just above the waterline to minimize the skidding. But he and Witty are especially pleased with how the boat responds to wakes, tending to cut through the waves without pounding, as you would expect from a wooden boat.

Heading back to the gravel beach where we launched DEIOPEA, I noticed Taggart still had high-enough regard for the Lyman folks of yore to remove the company logo from the old steering wheel and epoxy it to the center of the modern wheel. “I don’t mind running her up on the beach,” Taggart said as we did just that. “But I am glad it’s a Lyman.” Some things from the 1950s are indeed worth keeping operational, if not outright restored. ![]()

Lyman runabouts are commonly found on the used-boat market. For a good source of information about the type, contact the Lyman Boat Owners Association, P.O. Box 40052, Cleveland, OH 44140; 440–241–4290; www.lboa.net.

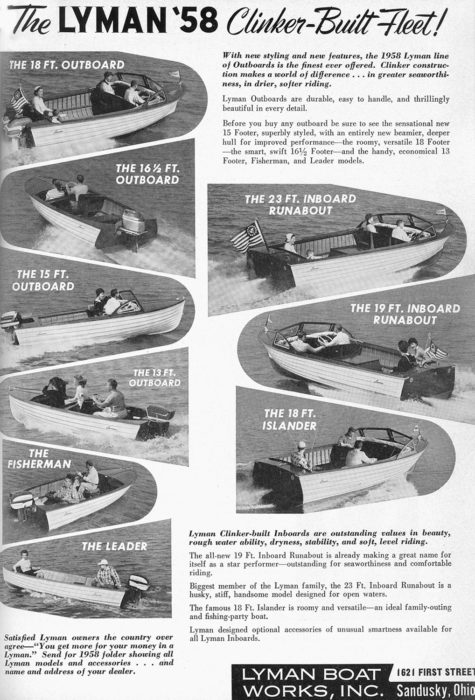

In 1958, Lyman advertised a full range of outboard runabouts, from 13’ to 18’. Its largest inboard-powered boat at that time was 23’, though in later years the company built boats as large as 30’. The company’s claim of durability has been proven by the fact that many Lymans are still in use today and are highly regarded by their owners.

DEIOPEA Particulars: LOA 16’6″, Beam 5’10”, Depth amidships 2’3″, Weight 650 lbs, Motor 50-hp outboard

About 20+ years ago, I found a Thompson of about the same vintage, and paid too much for it. When I got it home, I discovered the keel was badly hogged and split in the area under the forward thwart. It took a load of concrete blocks (with the boat supported at each end), plus a car jack, to restore the proper shape, and a Spanish windlass to squeeze the topsides back in, as it had spread badly in the same area, and plenty of epoxy to glue in a reenforcement. The forward deck was also in rough shape, so I made up some 3/8″ plywood out of doorskins because the boat was too wide to use standard width marine ply. Later on this proved to be a mistake, as you can easily imagine. Remarkably, none of the bent frames were broken, even at the significantly tight turn of the bilge aft. Unlike the Lyman in this story, my boat leaked when first launched, though not badly.

I also reenforced the transom with an athwartship piece of heavy aluminum angle (about 1/4″ thick, maybe 3″ X 6″). I ended up using a Mercury engine (used, of course) of about 60 hp, as I recall. I loved the handling of the boat on the Salish Sea (Puget Sound, north of the San Juan Islands), especially poking into a chop, as it was very soft riding. But off the wind, it had a scary tendency to root when slamming into the back of a 3′ wave, and would jerk on the steering in a disconcerting way. I never had the nerve to open it up in those situations, and to this day wonder how it would have behaved.

I eventually sold the boat, sad that my home-laminated “plywood” foredeck had delaminated rather badly. I lost track of the boat after that. It was a good looking boat, very much resembling the Lyman in your story. I always admired its lines.

My brother and I travelled down the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers to the Gulf, turned left to Panama City, Fla, about 40 years ago, in a Lyman with an inboard 4-cylinder Graymarine engine. It was a a great boat for the trip, anchoring at river sandbars and later on Gulf islands. My brother purchased the boat for $700 and we sold it for about half that months later in Florida. Thanks for the article and the reminiscing. The boat and the brother are now gone.