The small city of Rockland, Maine, has a big harbor with a strong working tradition. Although the unmistakable aroma of the fish-processing plant at the harbor’s north end is long gone, Rockland is still home to a handful of gritty commercial fish piers, some lobsterboats, herring trawlers, a few working boatyards, a Coast Guard station, a seaweed processing plant, the Maine State Ferry Service terminal, some day-charter boats, and a fleet of traditionally rigged windjammers. A harbor that can embrace all that activity is also big enough to be plagued by a significant chop that can build up inside the breakwater. Predictably and practically, the working boats there run to the large size.

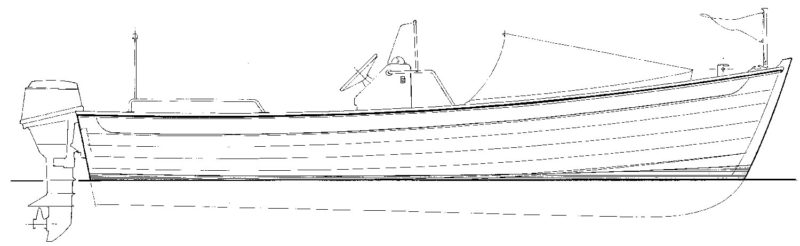

An exception to that rule is the new black work skiff that’s attending the fleet at the Apprenticeshop, a Rockland-based school for traditional boatbuilding and home to the Rockland Community Sailing program. Designed by accomplished local yacht designer Mark Fitzgerald and built by apprentices in the shop, the 17′ skiff is one of the better small yard boats I’ve operated. To start with, it feels like a workboat: heavy, stable, and predictable. While these aren’t characteristics I necessarily look for in a light recreational runabout of similar size, they are welcome in a workboat that I would normally think of as a bit undersized, especially to operate in the chop of Rockland Harbor.

With a 5′ 6″ beam, the boat appears narrow, and I feared that she’d be tender. But her mild deadrise of just 12 degrees at the transom means there’s a lot of buoyancy down in the chine, blessing her with admirable initial stability, even with my 200 lbs climbing over the narrow side deck. The boat has a designed displacement of 1,600 lbs.

When I visited Rockland in July, the Apprenticeshop crew was just launching an engineless 30′ one-design Haj-class sloop for the season, and director Eric Stockinger generously invited me to run the new skiff. I was already late to meet them at the shop’s launch ramp, so had little time to familiarize myself with the boat. There was no need to. It’s an advantage for a workboat that will be used by many different operators to be dead simple, and this boat is. I traced the fuel from the portable tank through a filter to the 20-hp outboard. There was no fuel shutoff or keyed ignition to worry about. I pumped the inline fuel bulb a couple of times, set the tiller throttle to start, and fired up the engine with a single pull of the start cord.

The Apprenticeshop

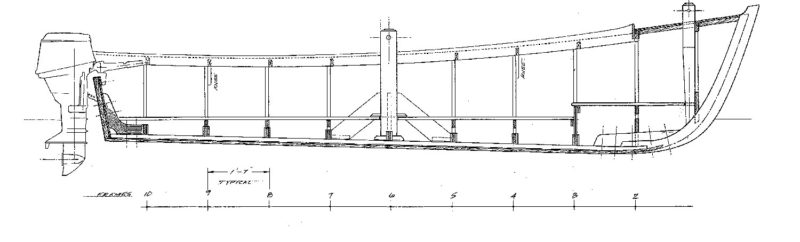

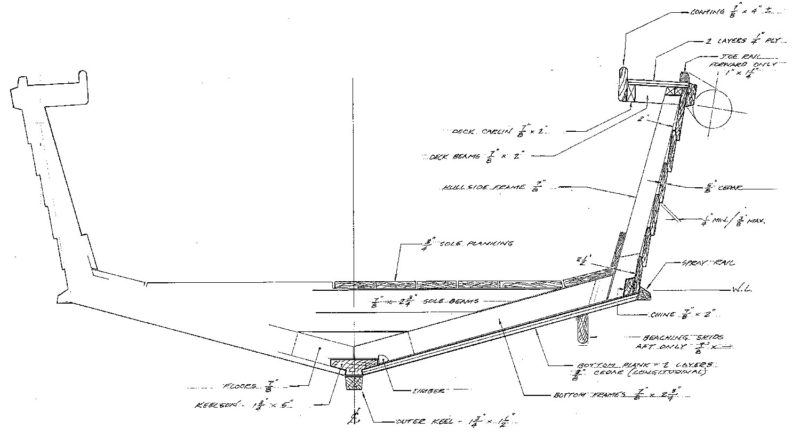

The ApprenticeshopThe AS-17’s framework is of white oak. Planking is of white cedar—two layers of 3⁄8” on the bottom, and 5 ⁄8” lapstrake on the topsides.

The Apprenticeshop

The ApprenticeshopThe deck’s rugged framing, which shows in this photograph, will soon be sheathed in plywood. The load on the heavy towing bitt is transferred to the keel via heavy knees.

Running over to the ramp at displacement speed, the boat tracked superbly, and I could rummage briefly for some lines to make fast to the Haj once I got alongside. While thus engaged, I couldn’t help but appreciate that the boat is uncluttered by thwarts, bulkheads, or a console. While that spare interior may not be ideal for most recreational vessels, it’s exactly what I want in a workboat where lines shouldn’t snag and line handlers shouldn’t stub toes or bark shins on furniture that’s just in the way.

As I nudged alongside the sailboat’s port quarter, the well-fendered work skiff didn’t bounce off as a lighter vessel (especially an inflatable) would. I stepped forward and made lines off, one to a stout galvanized cleat on the side deck (Stockinger noted bronze would look better, but economy is a necessary virtue in these times) and one to a sturdy samson post set in the short foredeck and running down to the keel deadwood for support. We backed away from the ramp, turned on the Haj’s short keel, and headed to the dock without fuss.

The beefy coaming around the long cockpit allows for lines to be handled from anywhere in the boat and run clear of obstructions. The only exception is the intentionally oversized oak towing bitt, supported by a natural hackmatack knee installed amidships. A line from even halfway up its height leading to a tow aft clears the low-profile outboard and allows the skiff to turn unimpeded without unhooking.

The Apprenticeshop

The ApprenticeshopThe AS-17 in its element: Tending to a Haj-class sloop that’s just been launched for the season.

The AS 17 Work Skiff was born of necessity as the Apprenticeshop’s need for a rugged utility boat grew to a critical point in 2011. The 40-year-old school and sailing center has an extensive series of floating docks to maintain as well as an ever-changing fleet of traditional boats and the community sailing fleet.

“We needed another workboat,” Stockinger said. “We didn’t want plywood, and we wanted something as open as possible.” At the same time they needed a boat that would be quick enough to serve as a tender for the youth sailing program, so a strictly displacement hull was out of the question. “A pretty little launch with fine lines and varnish just wouldn’t do it,” Stockinger said.

The quest for an appropriate model led not to a particular boat but to local yacht designer Mark Fitzgerald, best known for creating imaginative new powerboats with traditional aesthetic qualities for composite construction. The thinking was that the new workboat should look traditional but have the capacity to perform at high speeds, and this was a combination Fitzgerald had achieved many times before. The trick would be having him design it to be built with traditional heavy plank-on-frame construction.

Aaron Porter

Aaron PorterWhile designer Mark Fitzgerald specifies a top-end horsepower of 90, the Apprenticeshop’s new AS-17 is driven by a modest 20-hp Yamaha—an adequate amount of power for a boat meant to work around the waterfront.

“They’re so steeped in tradition,” the designer said. “I was honored when they asked me.” So Fitzgerald met with the apprentices and instructors who would be build-ing and using the boat to explain his ideas and gather more of theirs. Another consideration for the Apprenticeshop was the desire to have a model that they might offer for sale to potential clients. To that end Fitzgerald presented them with two models of the AS-17: a work skiff and an island commuter. The latter is essentially the same boat with 4″ additional freeboard to allow for safer, drier travel among Maine’s coastal islands.

Second-year apprentices Matt Dirr, Sophie Meltzer, Duncan MacFarlane, and Jeff Steele built the work skiff in the winter of 2011–12. Stockinger said they had to remind Fitzgerald that they wanted to build things “the hard way” incorporating labor-intensive details such as notched stringers that are valuable lessons, not hindrances, to efficient building. The boat was built upside down using the white oak frames as molds. In an effort to dispense with any athwartship support from bulkheads or thwarts, the sawn frames were made particularly heavy and gusseted with plywood at the chine and keel intersections. The keel and stem are of solid white oak, the bottom is two layers of 3⁄8″ white cedar planks laid longitudinally with the seams staggered and a coat of thick old paint spread between the layers, and the topsides are lapped 5⁄8″ cedar planks. The narrow decks required apprentices to build a complex supporting structure of deckbeams before applying a plywood deck. Fastenings were bronze screws, and copper rivets in the lapped topsides. A thick oak coaming and rubrail finished the deck edges.

Aaron Porter

Aaron PorterA bow pudding made of 1/2” manila line makes the new AS-17 a real pushboat, and adds an elegant touch.

“We were planning on hitting things with this,” Stockinger said by way of explanation after listing the robust materials and scantlings. That expectation informed the boat’s finish as well. Inside, the frames, planking, and Douglas-fir sole are simply oiled. They’ll weather with age, and the dings of dropped tools and flung gear will just add to her working character. The topsides are painted in one of my favorite practical finishes: Rustoleum flat black, a paint that hides the scrapes and gouges a working boat can’t avoid, and can be touched up with the scuff of a scouring pad and a dab of paint from a chip brush. As a finishing workboat touch, two apprentices artfully hitched a charmingly accurate bow pudding—a fender—of ½” manila line.

Running at speed with the 20-hp engine, the AS-17 Work Skiff makes 15 knots with the confidence-inspiring stability of a much larger boat. Fitzgerald said the new boat could handle 70 to 90 hp easily, and that’s the sort of power he’d suggest for the recreational version. As an able coastal runabout with real seakeeping ability and speed potential, this boat could be a slightly smaller rival to the Albury Runabout profiled by Maynard Bray in Small Boats 2010. As a versatile small work-boat, this model is hard to beat. ![]()

Mark Fitzgerald generously donated his designs for both models to the Apprenticeshop. For questions about commissioning either, contact Shop Director Kevin Carney at [email protected].

The AS-17 is a stoutly framed and beefy small skiff. Her diminutive size and 5’6” beam suggest a tender boat, but deep chines and 12-degree deadrise at the transom make her surprisingly stable. While conceived to be a workboat, she’d also make a great recreational runabout.

AS-17 Particulars: LOA 17’5″, LWL 15’10”, Beam 5’6″, Hull draft 11″, Engine draft 18″, Displacement 1600 lbs

Are plans available for purchase?

The Apprenticeshop was the source of the plans when the article published.There are no plans listed on their website.