The Guider, a new 18′ 7″ expedition boat from Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC), has been a development project for CLC’s designer, John Harris, and John Guider, a professional photographer and small-boat adventurer based in Nashville, Tennessee. The two have known each other now for 10 years and had previously collaborated on the Skerry Raid, a slightly beamier and partially decked version of CLC’s 15′ Skerry sail-and-oar boat. John G. used the prototype to travel the 6,500-mile “Great Loop” of the eastern United States. The Guider was designed and built for John Guider’s solo of the 2019 Race to Alaska (R2AK), a 750-mile human- and wind-powered race from Port Townsend, Washington, to Ketchikan, Alaska. Compared with the Skerry Raid, the Guider design features more storage space and comfortable sleeping accommodations, and has the seakeeping ability to push harder in rough and windy conditions.

Brian Forsyth

Brian ForsythFor approaching the beach, the centerboard is retracted and the rudder is lifted from its trunk.

To prepare for his summer 2020 expedition on Lake Superior, John G. brought his Guider to the CLC shop in Annapolis, Maryland, to be outfitted with a new cockpit tent arrangement. While the boat was in Annapolis, I was given the opportunity to sail it. A longtime beach cruiser and an aficionado of shallow-draft boats suitable for camp-cruising and sleeping aboard, I was delighted.

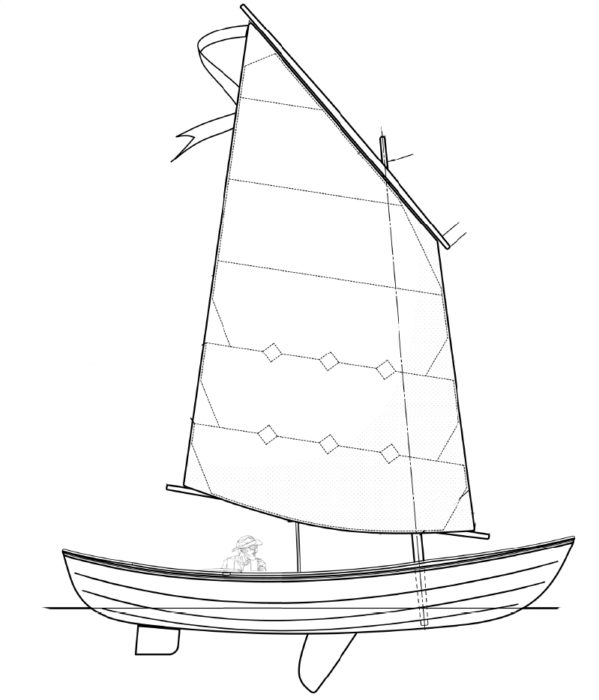

The Guider’s hull has fine ends and a relatively narrow waterline for easy rowing. The topside planks flare amidships to provide buoyancy and power under sail. The wherry-style plank keel is narrow but likely just wide enough to keep the boat upright on a beach or mudflat. The centerboard is a slightly profiled piece of 1/4″ aluminum plate, simple and tough. All spars are hollow and shorter than the boat for more compact trailering. The single balanced lugsail is 125 sq ft, about as big as a singlehander would want, providing plenty of oomph. Lazyjacks make sail handling manageable; the sail goes up and, more importantly, comes down in an instant. When lowered, the sail bundle is already mostly out of the way for rowing, and the lazyjacks can be snugged up to brail it completely out of the way, safely above head height. Two deep reefs are each set up with single-line reefing. All reefing lines and cleats are right where they should be on the starboard side of the boom, easy to use from a safe position amidships.

The Guider has decks fore and aft and side decks, making the boat significantly more seaworthy than a fully open boat. The side decks may look wide enough to hike out on, but with oars stored along the side decks in their locks and some purpose-made chocks, the decks are not available for sitting. This is an acceptable trade-off, as The Guider’s hull shape, beam, and intended stores and ballast should preclude the need to hike out. And the ready availability of the oars is the best I have seen on any sail-and-oar boat.

Brian Forsyth

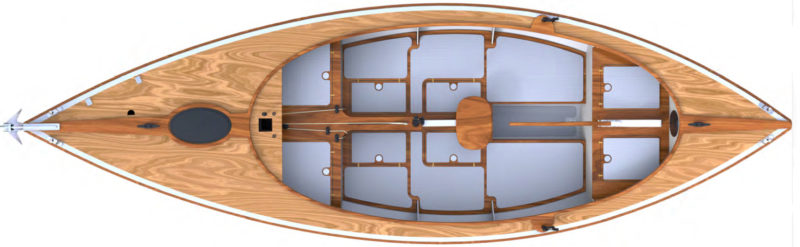

Brian ForsythThe interior has room on either side of the centerboard trunk for two to sleep comfortably. The aft end of the trunk supports a racing-style rowing seat. The boat has a dozen storage compartments and as many hatches for access to gear.

The defining design feature of The Guider, though, is its interior layout, optimized with 12 waterproof buoyancy compartments, most of which double as stowage for expedition stores with large, easy-to-operate plywood hatches. (The foredeck hatch has a large oval rubber kayak hatch cover.) The cockpit area is mostly a level space with just a small footwell set under the tiller. This makes for a quick transition to camp/sleep mode. I have slept, and attempted to sleep, in a lot of different small boats, and for an open boat, The Guider is as good as it gets. There are two spacious 6′ 6″-long sleeping flats, separated by the centerboard trunk and footwell. Nothing needs to be moved or reconfigured for sleeping. It can be as simple as rolling out a pad and climbing into a bivy bag in under a minute. In a few minutes more, you could rig a cockpit tent or sun shade.

Brian Forsyth

Brian ForsythThe rudder is housed inboard so it can be accessed more safely than a rudder mounted on the stern. The rudder is retracted here and the cassette that occupies the trunk when it is in use is visible.

The Guider’s rudder and tiller assembly is an elegant solution to an old problem. Traditional rudders on double-enders use either an overly long tiller or a long steering stick loosely coupled to a yoke mounted on the rudderhead. In either case, these stern-mounted rudders are difficult to retract or deploy (a potentially unsafe exercise in any kind of sea), and the tillers always seem to be in the way when you want to move around in the boat. The Guider’s rugged, retractable rudder slips through a dedicated trunk aft of the footwell. Above the rudder blade, the cassette, which the rudderpost pivots in, fills the well when the rudder is extended beyond the hull. It’s easy to deploy and remove the rudder from the safety of the cockpit. The rudder can be set halfway, with half the blade projecting, and left fixed as a skeg, for rowing. And the tiller pops up out of the way and clear of the boom with a simple bungee cord loop. Very slick!

After completing the design, crew at CLC built John G.’s boat, Guider #1, in 22 days. Yes, it will take you longer to build one. CLC sells Guider kits and components under a new group of designs called ProKits, intended for more experienced builders who don’t require step-by-step instructions. The construction manual, developed by CLC designer Dillon Majoros, consists of 38 full-color, richly detailed, 11″ x 17″ sheets and assumes the builder already has the skills required for stitch-and-glue construction, working with epoxy, filleting, and fiberglass sheathing. This project is a lot more complex than a plywood kayak, and while it could be built in a one-car garage, it wouldn’t be any fun. I would consider a two-car garage or similarly sized shop space a minimum workspace.

Currently the only way to build The Guider is from one of CLC’s kits. A full plan set will be available soon and will include a roll of full-sized paper templates for every wood part, so you cut them out from plywood sheets. Having built plywood boats from both kits and patterns, the precut kits are a no-brainer choice. As much as I love my high-end jigsaw, there are a lot of wood parts in this design. Let the computer and CNC cutter do what they can truly do better, more accurately, and much faster than you can.

Launching The Guider from a standard galvanized two-bunk trailer was a cinch at a ramp on the Severn River near Annapolis, although the trailer wheels were completely submerged to float the boat off. Prior to launching I had stepped the 30-ish-lb mast myself without difficulty and set up the running rigging and sail in its lazyjacks. For cruising, I think The Guider could be beach-launched with inflatable beach rollers; a strong crew would be an asset.

Ryan Kramer

Ryan KramerThe Guider has a single rowing station, so the second crew member can rest or attend to chores during lulls in the wind.

In a word, my overall impression of the boat’s performance under way was: “Easy.” With 300 lbs of crew (my daughter and myself) and 200 lbs of foam-wrapped lead ballast (called for in the plans) in the amidships storage compartments, the boat had an easy motion and became even more stable with the centerboard down. The Guider is easy to row, easy to sail, easy to switch between the two, easy to reef, and easy to beach. And easy is what I would want in an expedition boat, where conserving one’s energy is an important consideration.

Ryan Kramer

Ryan KramerThe 125-sq-ft balanced-lug sail has two lines of reef points. Under sail, with the board down, The Guider draws 36″.

Easy does not mean slow. The Guider could hold a GPS-measured 5-plus knots on any point of sail in moderate 10-knot breezes. It is a fun boat to sail, nicely balanced and responsive. The 3:1 mainsheet tackle is essential but enough to handle the big lugsail. There is something special about the way that sail pulls the boat on anything higher than a beam reach in a good breeze, like being lifted by a hot-air balloon. I have felt this before in catboats occasionally, at least until the weather helm made me aware how much I was fighting the laws of physics. But The Guider’s helm has a balanced “on-rails” feeling I normally associate with keelboats. I could control the boat with one finger on the tiller.

This is a “sit-in” or rather a “sprawl-in” boat. Without the need to hike out, I always felt secure at the helm in the roomy, deep cockpit with my feet in the footwell. With my daughter at the helm, the cleverly designed removable rowing seat, held in place with a single bolt and hand-friendly knob, was my preferred seat for serving as crew under sail. I could sit facing forward and tend the mainsheet. The racing-shell-style seat provides a comfortable rowing perch, with the footwell’s aft bulkhead providing rock solid foot bracing. I’d consider bringing along one or two small, inexpensive vinyl beanbag chairs, a secret comfort weapon for many small-boat cruisers.

Beaching The Guider and getting under way again was a piece of cake. The boat is easy to move under oars from the rowing position, whether rowing forward or backward, another benefit of the double-ended hull design. Under sail again, the 1/4″ aluminum-plate centerboard is an effective depthsounder and takes care of itself in the shoals.

There is no provision to add any sort of motor to The Guider, and it would be challenging and counterproductive to try. Thoughtfully designed to be a purely sail and oar boat, The Guider is best employed and enjoyed motor-free. If you are looking for a fully realized expedition-worthy craft that’s also a hoot to sail, I would highly recommend The Guider.![]()

Brian Forsyth learned to sail as a kid at Navy sailing clubs in the U.S. and overseas. After his own 20-year Navy career as an aviation maintenance officer and a second career as an information technology consultant, he is now free to mess about in boats as much as he wants. A former coastal-kayaking instructor and keelboat racer, he now sails, paddles, and builds small boats in Solomons, Maryland. He enjoys camp-cruising Chesapeake Bay with his sailing buddies, the Shallow Water Sailors, and is a member of the Patuxent Small Craft Guild, a group of volunteers who work in the boatshop at the Calvert Marine Museum.

The Guider Particulars

[table]

Length/18′ 7″

Beam/6′

Dry Weight/600 lbs

Ballast/200 lbs

Max payload/900 lbs

Rowing draft/9″

Sailing draft /36″

Sail area/125 sq ft

[/table]

The base kit for The Guider is available from Chesapeake Light Craft for $4,897.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Really appreciate this review. I’ve been wanting to hear details about this boat.

Thanks

Having grown up in Duluth, MN, on the shores of Lake Superior, and having sailed the Great Lakes in the Merchant Marine, I have the deepest respect (pun intended) for the incredible power of Lake Superior. I would love to hear more of the adventures of John G. on Lake Superior. What a great looking boat. I have to shift gears to think of cruising on Gichi-Gami, the “Great Sea”, in a small boat.

Love that interior!

Any info on the bilge pump setup?

Guider #1 has a manual bilge pump mounted on the aft bulkhead that can be operated while at the helm. The discharge is plumbed to a thru-hull fitting aft on the port side far above the waterline. The long intake hose can reach any place in the cockpit or cockpit compartments.

Brian, your Shallow Water Sailor website is very cool. Thanks for all the interesting sailing articles on the site.

Brad

Thanks for this. I have been wanting to build either this boat or the French Ilur. Tough choice.

Are there any pictures of this boat with the cockpit tent set up? It would be nice to see how that set up works.

I too would like to see the inside with the cockpit tent set up. This is a really nice boat.

Would anyone know the approx draft with the rudder fully deployed but the board fully up? Many thanks, David