Many years ago, I was looking for a daysailer I could easily trailer, rig, and sail singlehanded. It had to look good, too, with some traditional aesthetics. Crawford Boat Building’s Melonseed Skiff fit the bill.

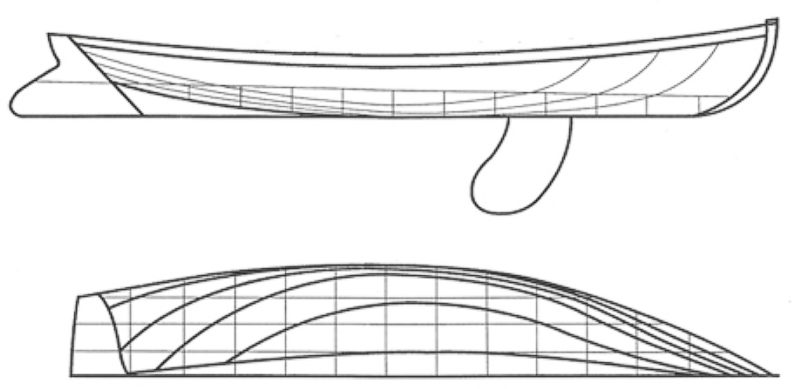

For over 30 years, Roger Crawford has been building his fiberglass version of the Melonseed Skiff in his small shop in Humarock, Massachusetts. He began when a decaying wooden boat, built to Chapelle’s lines in American Small Sailing Craft, was dropped off at his shop to be brought back to life. He restored the boat, took it sailing, and was so impressed that he wanted one of his own. He used the hull to make a mold he could build from, enlarged the cockpit, and increased the sail area. He has been busy building Melonseeds ever since, finishing them beautifully with teak rudder, tiller, rubrails, coaming, and floorboards, and varnished Douglas-fir spars. Anyone who has admired the lines in Chapelle’s book will recognize the low freeboard, hollow bow, curvaceous waterline, and enchanting tuck-up swooping from skeg to raked transom.

Courtesy of Crawford Boat Building

Courtesy of Crawford Boat BuildingThe spaces under the decks provide ample room for storing gear. A foredeck hatch facilitates access to items forward of the centerboard trunk.

Crawford builds his boats stout, with 1.5-oz mat, 0.5-oz mat, 32-oz stitched roving, and 10-oz cloth, doubled in the bottom, stem, and keel areas; the skeg receives 14 laminations. The deck is end-grain balsa core laminated between layers of 1.5-oz mat and biaxial stitched roving, with a nonskid finish that looks quite a lot like painted canvas. Solid fiberglass (without balsa core) in areas where there are through-deck fittings such as cleats, pad-eyes and oarlock sockets, assures peace of mind for years to come. The hull and deck are bonded together with epoxy, polyurethane adhesive, and stainless bolts and screws. Overlapped like the lid on a shoebox, the result is a strong, torsion-free unit.

Courtesy of Crawford Boat Building

Courtesy of Crawford Boat BuildingThe PVC centerboard will lower itself with its own weight; a cord and a clam cleat will control its depth and allow it to retract upon striking an underwater obstruction.

Crawford built his first 99 boats with the traditional scimitar-shaped teak daggerboard as recorded by Chapelle. Starting with number 100, the boats have a 1/2″-thick PVC centerboard raised and lowered by a simple pennant. He engineered the centerboard to have sailing characteristics as nearly identical to the daggerboard as possible. I have owned and sailed both versions and find a negligible difference between the two. The daggerboard trunk is entirely forward of the cockpit, whereas the centerboard trunk, at deck level, intrudes into the cockpit about 4″, an acceptable trade-off for the convenience of a board that self-stores, pivots when grounding, and offers infinite adjustment.

The shallow hull with a barn-door rudder that does not extend below the skeg makes this boat well suited to the shallows, and with a 6″ draft with the centerboard up, one can glide and slide over some very skinny water indeed—perfect for creek crawling.

Steve Siegert

Steve SiegertThere isn’t a thwart for rowing, so a couple of boat cushions will get the rower into a comfortable position high enough off the floorboards. The sail and all three spars for the sailing rig can be stowed below deck when they’re not needed.

Crawford has taken great pains to keep the boat as simple as possible, which makes getting on the water an easy proposition. Rigging is straightforward and the free-standing rig makes getting underway quick. The sail is kept furled around the mast and together they weigh about 15 lbs. Stepping the mast is a simple matter of inserting it through the partner on deck and into the step below. Hang the rudder on the gudgeons, insert the tiller, and reeve the single-part sheet through the block on the rudderhead. Unfurl the 62-sq-ft sail and insert the sprit end into the becket at the peak and push up to spread the sail. Cleat off the snotter with enough tension to give a crease between tack and peak (it will disappear when the sail fills). Clip the sprit-boom snap hook to the clew and tension and cleat the boom snotter. It’s customary to rig the sprits on opposite sides of the sail so that the asymmetry averages out. The sprit boom seems to cut into the set of the sail more than the sprit, making the favored tack the one with the sprit boom to windward.

When you board, either from the dock or the shallows, step toward the center floorboards. The boat can feel a bit tiddly until the firm bilge submerges. Once you’re seated on the floorboards, the boat is very stable.

Courtesy of Crawford Boat Building

Courtesy of Crawford Boat BuildingThe sheet is lead forward from a block on the rudderhead so the sailor can steer and hold the sheet with one hand. A cleat under the tiller can hold the sheet when it’s safe to secure it.

I find the ideal trim for singlehanding is to sit about even with the oarlock sockets, adjusting fore or aft according to conditions. The tiller comes naturally under your hand. Those accustomed to mid-boom sheeting will quickly adapt to the sheet running forward from the block on the rudderhead to your hand.

Once in the cockpit, there’s little need for moving about, other than changing to the windward side when tacking. This is not a boat that you stand up and walk about on. It wants your weight low and inside the cockpit. Setting sail is most easily done on the beach or the dock because the hollow bow and fine lines make it skittish if you go forward on the deck. I have done so many times, to furl or set the sail, or re-tension the snotter, but it does require good balance. If going forward is necessary, it’s safest to sit or kneel on the deck. Another person sitting aft in the cockpit will keep the stern down and help to steady the motion.

The cockpit is a little over 6′ long—big enough for two people and a picnic. There’s room up under the deck for a cooler, anchor, and other gear, and a 10″ x 10″ hatch gives access to the forepeak. The 7 -1/2′ oars store under the side decks. At 5′ 9″, I fit comfortably with my back against the coaming and feet in the lee bilge, with the reassuring sense that I’m down in the boat, not on it. Because seating is on the floorboards, knees, hips, and lower back need to be supple enough to tolerate that position. When sailing with a crew, the usual arrangement is to sit on opposite sides, facing in. This balances the boat nicely in most weather. In stronger wind, both skipper and crew sit on the windward side of the cockpit. The boat is very responsive to trim and weight distribution, so adding the weight of the crew to windward makes the boat stand up well to more vigorous breezes.

Courtesy of Crawford Boat Building

Courtesy of Crawford Boat BuildingThe Melonseed resists heeling well and often allows the sailor to sit on the downwind side in moderate breezes.

Despite the low-aspect, low-tech rig, the boat’s windward ability may surprise some folks. Although it doesn’t point like a Laser, it goes very well to weather. The spritsail doesn’t like to be strapped down too hard, and if it is, you’ll feel the stall. Give it a little room to breathe and the boat comes alive. It’s easy to find the sweet spot because the feedback from trim changes is immediate and obvious.

As the boat responds to a puff, the weather helm encourages it to head up, making it easy to naturally climb the lifts. Sailing fairly flat gives the best boat speed, but I find sitting out to windward in anything less than a Force 4 is unnecessary. In higher winds, sitting on the deck keeps the boat on its feet, reduces leeway, and maintains speed. When working to weather in a tie-your-hat-on breeze, you’ll need your foulies as spray sweeps the deck and cockpit and is tossed up into the sail. You’re plugged directly into the experience through the direct connection to sheet and tiller and the motion of the boat; the low freeboard and spray contribute to the sense of speed and adventure.

Because of the boat’s light weight, approximately 230 lbs all up, there’s little momentum to punch through steep chop hard on the wind. Easing the sheet and your course off the wind a bit will increase speed and deliver a palpable in-the-groove feeling. While it may require an extra couple of tacks, you will arrive at your windward goal far sooner than if you try to jam your way to weather.

When tacking, the natural weather helm does most of the work. I usually release the tiller with a slight nudge and let the rudder swing of its own accord. As the bow turns through the wind, I scoot over to the other side of the cockpit. By that time, the bow is falling on the new tack and I center the tiller and trim the sail. Coming about in a big chop requires that you sail through as opposed to relying on momentum to carry you.

Courtesy of Crawford Boat Building

Courtesy of Crawford Boat BuildingThe sail is not equipped with reef points as most owners don’t find them necessary. When the breeze stiffens, the peak of the sail gets twisted to leeward, spilling the wind. The twist reduces the effective sail area and lowers the center of effort, reducing the heeling force.

If you get caught in irons, you won’t be there long. Because the mast is in the eyes of the boat, you can easily back the sail to swing the bow off. If you raise the centerboard and back the sail, the boat will pivot in place, a useful tactic when maneuvering in tight spots.

This boat will spoil you for jibing. The sprit-boom keeps the foot from rising and the single-part sheet runs smoothly through the block as you ease the sheet at the end of the jibe. Jibing is a casual affair in moderate conditions and doesn’t require much sheet tending. Higher winds demand more prudence and control. In Force-5 conditions, I opt for the “chicken jibe,” looping to windward to bring the boom across, then falling off on the opposite downwind tack. One of the benefits of the free-standing, rotating mast is that the sail can be luffed out forward of the mast to flag out ahead of the boat in certain situations, like easing into a lee shore landing in mild conditions.

Control downwind is good, as the sprit-boom exerts its self-vanging effect to limit the twist in the sail. There is, however, a golden rule: To prevent the white-knuckle “death roll,” don’t allow the peak to go farther forward than perpendicular to the boat’s centerline. Leaving a bit of centerboard down helps maintain directional control, and I usually scoot aft a trifle to give the rudder a little more bite. The tucked-up quarters and raked transom prevent the stern from dragging.

The hull’s theoretical maximum speed for the 12’ waterline is 4.6 knots, and the boat seems to get up to hull speed easily. I can’t confirm this with GPS data, but I once sailed on one tack for 8 miles, closehauled, in a 12–15 mph breeze. I loosely timed the leg, and the resultant math showed a bit over 4 knots, which I thought impressive for sailing closehauled into a chop. The boat really struts its stuff on a reach, with the bow wave bubbling along the side deck. In the right conditions running before the wind, it’ll plane for short distances, and sometimes surf down the backs of the waves.

Crawford’s early boats were equipped with reef points. Reefing can be done, but it requires rigging a halyard and longer snotters which complicates the simple setup. In those early years, Crawford decided that the reefpoints were superfluous because the boat is so capable in such a wide range of wind speeds. No one was using them anyway. In reality, if you think the boat needs a reef, you probably shouldn’t be out there. Scandalizing the sail by dropping the sprit and letting the peak of the sail fold over is useful in a hard chance, but pointing ability will be compromised.

Bruce Gordon

Bruce GordonThe 62 sq ft sail has enough area to provide pleasant sailing in light air. The spars are Douglas-fir and the trim, tiller, and rudder are all teak.

A 10–15-mph breeze is magic, but the Melonseed will ghost in a whisper and tromp happily to windward throwing spray in 20. I have sailed in mid- to high-20s with gusts over 30 and the boat took it in stride.

Capsizes are rare, and all I know of were caused by a cleated sheet that wasn’t freed quickly enough in a gust. The small clam cleat on the tiller can be used to relieve your grip on the sheet, but the sheet should stay in hand in all but the mildest breeze, cleated or not. The full bilges do a good job of resisting heeling once submerged, and the peak of the sail tends to depower as it twists off a bit in the bigger puffs. Solid water creaming alongside the coaming is your cue to ease off. But there is a point of no return, when solid water over the coaming fills the cockpit and you wish you had eased the sheet. The boat has flotation under the decks and will float upright when swamped.

On those days when the breeze is elusive, I “power-sail” through the flat spots with a few strokes of the leeward oar. It’s also possible to row off a lee shore in moderate conditions with the sail set. You can leave the sheet unclipped to allow the sail to luff without the chance of it wrapping around the tiller. Be prepared for the foot of the sail to take a swipe at your hat.

Roger Rodibaugh

Roger RodibaughThe boom and the sprit are set on opposite sides to even out their effect on port and starboard tacks. THREE CHEERS, shown here, is the author’s Melonseed, hull #463 .

Although you can row with the rig struck down inside the boat—the 10′ spars fit entirely under the decks—I prefer to leave the rig ashore if I’m rowing just for the pleasure of it. The boat carries well between strokes, tracks well, and isn’t knocked off course by a cross-chop. There is no thwart—sitting on a couple of cushions puts me at the right height. Crawford has an optional foot brace that bolts to the floorboards with wing nuts and can be positioned specifically to suit the rower.

Since I keep the boat in the garage and haul it to the water for each sail, ease of trailering is an important consideration. With the spars stowed in the boat alongside the centerboard trunk, the Melonseed makes a neat, streamlined package for towing. The boat and trailer total less than 500 lbs, so it’s an easy pull even for a compact car.

The combination of easy trailering, simple rigging, sure-footed wholesome performance, and traditional aesthetics have made Crawford’s Melonseed Skiff the perfect daysailer for me and has delivered decades of enjoyable, uncomplicated time on the water. ![]()

Roger Rodibaugh, despite living in landlocked central Indiana, has been sailing for 50 years. He credits the sailboat on top of his first birthday cake with starting it all. He recently retired from chiropractic practice and sails his Crawford Melonseed Skiff, THREE CHEERS, on Summit Lake and Prairie Creek Reservoir. He’s looking forward to the sailing season of 2021, which will be his 30th in a Melonseed.

Melonseed Skiff Particulars

Length: 13′ 8″

Beam: 4′ 3″

Displacement: 235 lbs

Sail area: 62 sq ft

Cockpit length: 6′ 1″

Spar length: all 10′

Weight: 235 lbs

Finished Melonseed Skiffs, complete with standard equipment, are available from Crawford Boat Building for $15,500. (Prices updated March 2022)

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

For one of the very best of all the Melonseed videos open this link. Turn up the volume as the music is wonderful, pour a glass of your favorite beverage and watch some beautiful sailing.

Perhaps the best of the small traditional craft for recreation. Few have survived and I suspect that most of the Jersey gunners used the cheaper sneakboxes. The Seaford skiffs of Great South Bay on Long Island seem to have been more common, are shaped about the same but have a built down keel and are centerboarders, instead of the sprung keel and daggerboards of Melonseeds and sneakboxes.

Folks – with all due respect to the long time Melonheads on the eastern seaboard and others far and wide; you have just heard from the Master of the Midwest Melonheads, a group of fun-loving kindred spirits that ‘RJR’ as we call him, started gathering together back in 1999 (I think it was) for a week long gathering known as the Melonseed Midwest Rendezvous or MSMR as we’ve called it. It is truly a blast and we look forward to it every summer – well except this past one. RJR will shy away from this designation, but I believe he has done more to celebrate and promote this wonderful sailing craft than any other, short of Roger Crawford himself. For some of the most evocative video of the Melonseed you’ll ever see, check out John Masella’s YouTube channel.

And for a glimpse of RJR’s familiarity with this wonderful little skiff, check out the bit from my 2013 MSMR vid starting at about 2:05:

I’m blessed to have taken my first ride in RJR’s Melonseed in 2001 and then went home and ordered up a boat. Try one and you may do the same!

Doc Musekamp

Oshkosh, WI

MS#178, Pearl

Great article, RJR!

Informative with a beautiful layout. Along with Roger Crawford’s website, it’s my new link to send to folks I’m trying to convert to a Melonseed.

This is the Way.

Holly Bird

Palm Harbor, FL

MS#268, GOSHAWK

Your wonderful article on the Crawford Melonseed was a cruel reminder that it is still March in New England and still a bit early to get back on the water in my Melonseed! Instead I went out to the garage to give it an admiring look and a pat on the gunnel.

Digger Donahue

BOLD O’DONAHUE Hull #534

Digger, there’s a lot to be said for having your little darlin’ in the garage where you can give her a look and an affectionate pat—day or night and in all weathers. My Melonseed lives in the garage and the daily view has gotten me through many, many winters and fanned the flames of anticipation for the new season. Wishing you an early and long season on the water.

RJR

Beautiful lines on this Crawford Melonseed. I very much enjoyed the article and the video of the boat in action! Thank you.

My Melonseed, SERENITY, (#241) is a joy to sail. It really doesn’t get any better than this.