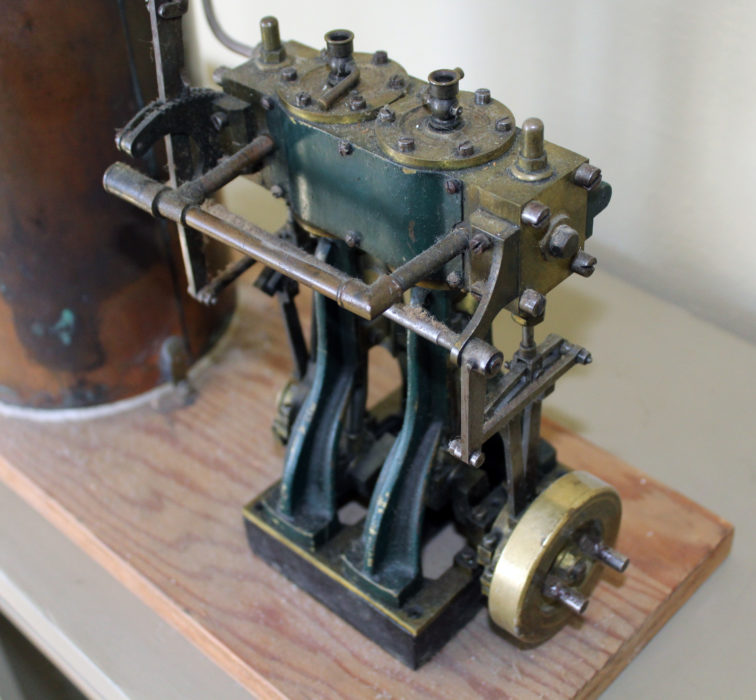

In my tweens my father let me play with a model steam engine that my grandfather had built, so I was told, from a Stuart Turner kit from England. I’d occasionally take the engine, its boiler, a small crescent wrench, a box of matches, and a handful of black licorice and set up on the concrete patio in the back of the house.

Stuart steam engine models date back to 1898. I’d guess that my grandfather’s is now about 90 years old. It doesn’t have a lot of hours on it and still runs smoothly.

After removing the pressure-release valve I could trickle water into its fitting until the water showing the gauge on the front of the boiler was almost to the top of the glass tube. I’d replace the valve, then fire the boiler with either an alcohol burner that Dad bought for it, a can of Sterno, or wood scraps. I preferred wood for the glowing golden flames at the mouth of the fire chamber and the plume of smoke issuing from the chimney.

The model is powered by a copper boiler secured to the plywood base over a circle of fire-proof jeweler’s soldering board.

As the pressure built, some of the fittings on the boiler would begin to hiss and spit. The whistle on the top of the boiler was my only means of checking the pressure. It would lisp when the pressure was just beginning to build, and with good head of steam, it would scream shrilly when it was time to open the valve to send steam to the engine. The brass flywheel might’ve also needed a bit of a nudge to get it spinning.

The engine never propelled anything, but it was pleasure enough just to watch it and listen to it—I’d sit by it eating licorice until the water level in the gauge dropped to the bottom and it was time to extinguish the fire.

When John Leyde invited me to take a run in a steam-powered boat up the Ebey Slough from Marysville, a half hour north of Seattle, I was eager to watch a steam engine put to use. John helped a friend build ATNA, an Adirondack guideboat that was featured in our January 2018 issue.

The propane burner in the boiler has not yet built up a head of steam, and all’s quiet.

The steam launch E. SCOTT HAMMOND is just one of the many boats John has built. Its lines were inspired by a Karl Stambaugh cruiser that John scaled down to half for an electric launch, then stretched to 18’ for the HAMMOND, launched in 2009, which was initially diesel powered and then converted to steam on 2016. The switch was one John was destined to make; his father worked with a logging crew in the Washington forests and ran a steam donkey, a powerful seething machine with a tall boiler and a powerful winch, all mounted on a pair of hip-high log skids.

courtesy of John Leyde

courtesy of John LeydeJohn’s father, Ralph, here sits on the winch drum of the steam donkey he operated. Grandfather Leo is behind him, and John’s uncles, Paul and Glenn Leyde, are in shirtsleeves standing in front of one of the log skids. The donkey was behind hauled between work sites where it was to be set on the ground, resting on the skids.

The engine for the HAMMOND was built in 2004 by a steam buff in Oregon. It has a 2-1/2″ bore with a 3″ stroke, making it a 241 cc engine, although it’s not just the top of the cylinder that does the work. The piston gets pushed by steam from above and below.

John’s steam engine pushes the HAMMOND along at about 4 knots.

The piston is lubricated not by oil, but by water condensed from the steam flowing into the cylinder, and the water is recycled in the hot well beneath the boiler where it will be turned into steam again. It is possible to use oil to lubricate the cylinder, but the water to be recycled gets contaminated with oil. John tried an oil-lubrication system once, and to filter the water before it reached the hot well, he ran it through a homemade filter: pantyhose filled with hair clippings from his local barber shop.

The boiler is propane fired, so there’s no smoke coming out of the stack. There are two propane tanks secured under the foredeck. With two tanks, John can switch as one becomes cold, even icing up, and interrupting the delivery of fuel as it is consumes at about 1-1/2 gallons per hour. There is a freshwater tank under the HAMMOND’s aft deck, and the water it supplies goes through a heat exchanger warmed by the engine’s exhaust to make the boiler more economical in the amount of fuel it consumes to create steam.

A bronze 16×20 propeller pushes the HAMMOND along at about 4 knots. It’s a good thing that she doesn’t go much faster, because John spends about half of his time tending the engine, checking the boiler, and going forward to check on the propane tanks. “Never take a date out on a steamboat,” he said, “you’d just be ignoring someone.” I took the initiative to keep an eye on our course up the serpentine bends of the slough, and often reached across the cockpit to turn the wheel, mounted on the portside coaming. I too let a lot of shoreline slip by without notice. Watching a steam engine is very much like staring into a campfire: it’s soothing, almost mesmerizing.

I’ve been using a very reliable 2.5-hp outboard for a dozen years, and as happy as I have been with it, I don’t really take pleasure in it because it doesn’t make for good company. With two of the boats we use it on, I’ve abandoned its tiller and put some distance between the helm and the motor so I don’t have to put up with its constant thrumming and quivering. John’s steam engine is a much better companion, soft-spoken and more open—it doesn’t hide behind a cowling and an engine block.

I’ve often thought I’d make a model launch scaled for the Stuart Turner engine, but while I might enjoy seeing the boat underway, I’d miss watching the workings of the engine.![]()

Too cool. Great stuff! Bill Garden would have loved it.

R

If anyone is interested in steam boats, locomotives, cars, etc., check out the Northwest Steam Society.

$20 a year for membership and quarterly news letter with lots of advice and wisdom on steam projects.

…or in the UK, The Steamboat Association of GB. They also run a forum which may answer some of the technical questions here.

The 1962 Boatbuilding Annual from Sports Afield magazine featured a 20′ steamer by David Beach. Had a plywood V-bottom hull and was double ended. He suggested an engine made by the Semple company, if I remember correctly.

That was a great series of magazines, and at one time my dad had most of them, which I inherited. There were some good designs, by Beach, Edson Shock, Bruce Crandall, Weston Farmer, and Rogers Winter. One designer, Hi Sibley, drew some of the ugliest designs ever produced by a sentient being. And one, who shall remain nameless (as I have an aversion to litigious attorneys), stole designs from other naval architects. One of those was for a husky outboard utility/fishing boat originally by Luther Tarbox, and another of a low-powered displacement cruiser by John Atkin. This design thief would copy the lines exactly, and reproduce almost word for word the introductory rationale for the design parameters. I never heard whether any of his victims tried to bring him to account.

My dad actually built a little 8′ plywood skiff from a How to Build 20 Boats magazine, and I enjoyed it for fishing and dinking around for quite a few years.

I was very sad to see the demise of those magazines, as they provided a lot of material for daydreaming. There was also “How to Build 20 Boats,” and “Boatbuilder’s Handbook”, which featured designs by William D. Jackson. “Mechanics Illustrated” and “Science and Mechanics” were publishers of some of these, and there were others.

Of course, the advent of fiberglass and aluminum boats that you could buy at your local department store put and end to these great publications.

In the mid-fifties, while on vacation in Stonington, Maine, my father picked up a 6-hp steam engine with a Stevenson Link that had been salvaged from an old logging tug. The engine followed my parents through 13 moves for 50 years while my father dreamed of building a suitable launch to go around it, but sailboats always prevailed. Nonetheless, for many years in the sixties he subscribed to Light Steam Power, which I loved to read and look at as a kid. Lots of great photos and drawings of steam launches and other contraptions. The engine was about 4.5 feet tall and weighed hundreds of pounds; my father kept a set of wooden rollers around for the sole purpose of moving it when needed. My mother used to joke that she was going to put a lampshade on it and turn it into decor. Eventually, my father realized the boat wasn’t going to materialize and donated the engine and what he knew of its provenance to the Lumbering Museum in Patton, Maine. Anyone with nautical steam ambitions who could find any old issues of Light Steam Power would find much to enjoy.

Darn! Since my Naval architecture days at Michigan,I’ve dreamed of building a steam launch. Now at 80 years old and three boatbuilding projects behind, it seems I need to refocus. These wonderful articles keep the dream alive.

One of the Northwest Steam Society members is 91 years old. Last year, he went steaming in his boat 76 times! He continues to improve on the boats and engines he has built and is a great inspiration to the rest of us club members.

Like your grandfather’s engine I am 90 years old. Before WW II, Japan made a model steam boat you could run with a small candle. I spent hours running it in the bathtub. I then got a paper route and was able to purchase a running steam engine. My father worked on a steam boat on the Great Lakes, so each summer I got to see real, big steam engines. Brought back a lot of memories. Very good article.

I don’t understand the piston being lubricated by water. Water would be the last thing I would want even close to a piston. Perhaps I am still tied to thinking about internal combustion, and this is, after all, water-pressure (steam-pressure). So what material are the pistons made from that they can be “lubricated” by water? Thank you.

I don’t have an explanation on a scientific, molecular structure level, as to the ability of steam to act as a lubricant. All I know is that it seems to work, although, there will be some wear in the mating surfaces of the cylinder and the rings. Some of the newer engines have Teflon rings which would cut down on friction in the cylinder. Stainless steel would be a good bet for rings and pistons. My humble opinion is that wear in the cylinder and rings is acceptable as opposed to the possibility of introducing oil into the boiler which would render it inoperable. Boilers are very expensive and rings are relatively cheap.

I’m hoping someone can put me in touch with John Leyde, I’d like to ask some detailed questions about the Hammond’s hull and its design/construction.

I’ll send your note and email address to John.

—Ed.