I’ve been exploring my local areas by bicycle for as long as I can remember. In the mid ‘70s I was living in Edmonds, Washington, and took a ride about 8 miles north to the outskirts of Mukilteo, a town on the shore of Puget Sound with a little-used airfield on its eastern inland side. An industrial park had been established in the two-story white clapboard buildings that had been left behind by the Army Air Corps. JanSport occupied one of the larger buildings with its production facility and customer service was housed in a smaller one with unpainted cedar siding, which had turned almost black with age on its south-facing side. A large green dumpster was set right alongside the larger building; it was about 18′ long and 7′ high, so I had to climb the welded-on ladder rungs to see what was inside.

What I found wasn’t at all garbage. All of the sewing scraps from the shop in the upper floor had been tossed through an open window. There were remnants of ripstop, coated nylon, Cordura, leather, webbing, zippers, cord—everything that went into the backpacks and dome tents that JanSport was making then. There were also rolls of new fabric still on cardboard tubes, thrown out because there wasn’t enough left to supply the pieces needed.

I’d been raised by parents who lived by a credo that my sisters and I adopted: Don’t buy what you can make, make do with what you can find. I’d been sewing since I was 10 and in the dumpster I found everything I’d need to outfit myself for backpacking in grand style. I couldn’t carry anything home by bicycle, so I decided to return with my mother’s car to make a haul.

I borrowed her navy-blue Volkswagen squareback and came back that evening and loaded it up with everything I thought I could use to make my own outdoor gear. That was the first of many trips. I kept a low profile and watched the buildings before approaching the dumpster. I noticed that the people working in customer service would fill a garbage can with returns and damaged products before leaving for the day at 5. About 30 minutes later, a truck would come and haul the contents of the garbage can away. At a quarter past 5, I’d take what I could carry, leaving the can half full to avoid suspicion, and walk it back to the car.

Almost everything from customer service had been slashed with a razor or utility knife, I assume to assure employees wouldn’t collect it or sell it, but the damage wasn’t a deterrent for me. The tents had been slashed while in their stuff sacks so the damage to the tents themselves was quite irregular. I repaired two 3-person dome tents, a wedge tent for two, and a few backpacks of different sizes. They all had an Edward Scissorhands look after I sewed them up but were as functional as they were when new.

I made many visits to the dumpster over the course of a few months, but the harvest came to an end when it was replaced by one with a screened lid and a padlock. I wasn’t too sad about it—I had collected enough material to make a lot of gear—nor was I too surprised. My father had told a few of his students, kids about my age, about the dumpster and I suspect they had been less discreet than I had been.

I had a dozen or so roll ends of fabric. One of them had several yards of light-blue coated nylon. I recognized it as the material JanSport used to make the tent rainflies I’d salvaged and I used it for stuff sacks, rain chaps, and a tarp. I didn’t use the tarp for backpacking because my tent and fly were my shelter from the rain. But I did take the rainfly on my first small-boat cruise. I brought it mainly as a ground cloth for shore camping and hadn’t anticipated the many other ways it would make itself useful when I had to sleep at anchor or wanted to make use of a light breeze. The tarp became part of my regular kit and accompanied me for over 4,000 miles of cruising and even provided a couple of hundred miles of surprisingly effective service as a sail.

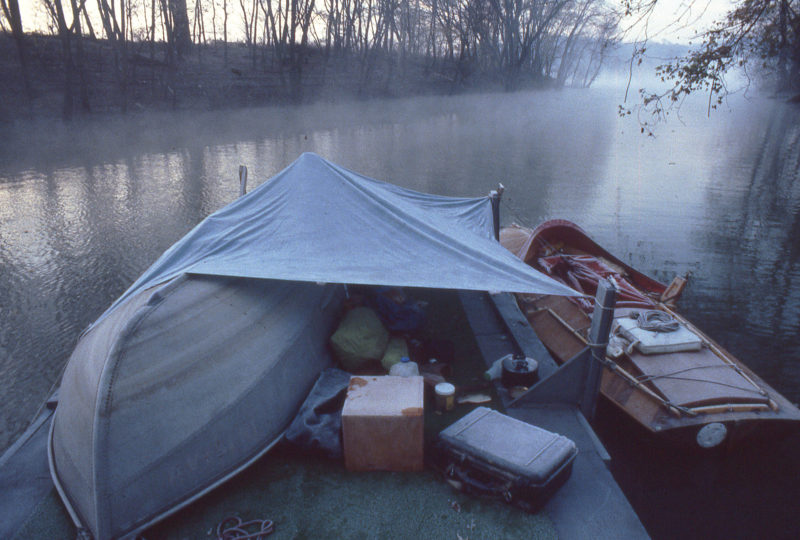

The simplest use of the tarp was as a boom tent. Rather than use the mast to support the boom, I made crutches from driftwood. The mast tended to thump when the boat rocked, a noise that kept me from falling asleep. I took this photo during a 700-mile cruise of the Inside Passage.

On that first Inside Passage cruise, I rowed and sailed a 14’ Chamberlain dory skiff. For light following wind I used the blue tarp as a spritsail and set it opposite the boat’s regular spritsail, using the topmast as a sprit. While spritsails usually have a high peak, Norwegian snekker have spritsails that are very nearly rectangular. The tarp nicely balanced the sprit mainsail, set here, but mostly out of frame to the left. With the nearly symmetrical rig, the skiff had a neutral helm.

Set on a line spanning a creek that empties into the Ohio River, the blue tarp was my shelter for a rainy night spent in my sneakbox.

One of the other shelters I made with the tarp used the camera tripod for support.

I picked a raft as a place to sleep on an especially cold night just off the Ohio River. The tarp kept some of the frost off me but nothing more. I didn’t sleep at all. I would have been better off sleeping in the boat where I would have found a bit more protection from the cold.

On a downwind run off Florida’s Gulf Coast, I ran with the main set to port and the blue tarp to starboard, helped out with a board I found on the beach to serve as a whisker pole.

When the sneakbox took the wind over the starboard quarter, I sailed on a broad reach and moved the whisker pole forward. With the tarp, jib, and main all drawing well, the sneakbox got up on plane.

I hadn’t finished the squaresail for the Gokstad faering I built for my second Inside Passage cruise and it took a few evenings of sewing to get it ready. In the meantime, the tarp served in its stead, using the tiller extension as a yard and the squaresail’s yard as a mast.

Alaska’s Seymour Canal is a 34-mile-long inlet that separates Glass Peninsula from Admiralty Island. When a very light breeze from the south ruffled the water, I was ready to take a break and sail. The squaresail wasn’t providing much speed, so I rigged the tarp to quicken the pace. The only way to hoist it was to tie its gathered end on the mast’s backstay; an oar tied to the tarp’s bottom edge spread it out.

With the tarp to starboard and the tiller extension holding the squaresail to port, the faering caught as much wind as it could and moved a bit more smartly.

I joined a group of kayakers for a three-day outing/paddling tour of Ozette Lake on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. When the morning of the second day offered a wind that would take us directly to our next camp, I was reluctant to pass up the free ride and talked the group into rafting-up to sail. There were six of us when we began sailing, but the kayaker who had been on the left side got peeled off when we got up to speed and couldn’t catch up. I dropped back to take some photos and with a short sprint I was able to rejoin the group.

It has been over 40 years since my JanSport dumpster dives and the tarp, the rain chaps, the stuff bags, and the tents are all gone. The coatings peeled off and the fabric took on an unpleasant odor. All I have left is a backpack with the stitched-up scar running from top to bottom. I still don’t buy what I can make—there’s great satisfaction in that. And I still make do with what I can find, nurturing an appreciation for a generous world’s gifts of serendipity.![]()

What a great dumpster to find! I think we all have stories of useful resources that were our secret treasure troves, now long gone.

Hi Christopher,

Just thinking ,after reading your excellent piece: maybe we should make “Dumpster Diving” a compulsory subject in schools?

In our world of instant gratification and throw-away culture it’s well past time to teach our children a change of tack.

Lucky you to be encouraged to sew at an early age!

Chris,

I started reading about your Inside Passage sail/row and thought that was a great story about hearing from little Bergie many years later.

I’ve noted that in some marinas dumpster diving is a community effort. It often takes the form of a community exchange. Not all diving is good, though. One person’s garbage is another person’s trash.

My town dump here west of Boston had amazing discards from light industrial cast-offs. That was 45 years ago. Today half is now a recycling facility, the other half is a soccer field. I just rediscovered that fun from those days recently by searching a metal dumpster for “welding material.” Also scored was lawn mower, rototiller, and cement mixer—all working. I promised myself to always leave more than I take

My belief is in Re-purpose, Re-use, Re-upcycle before purchasing new.

We have a town recycling center or dump as well. Everything is priced right—Free. My scores have been big roll of outdoor carpeting, two oak tables (one 6′, on 8′, with leaves that looked new), two adding machines that I took apart, and $120 stuffed in the springs under some drawers.