Mersea Island, tucked into England’s Essex coast about 50 miles east northeast of London, is only truly an island twice a day, when the high tide covers the causeway that connects it to the mainland. There’s open water to the island’s southeast side at the junction of the Colne and Blackwater estuaries, and to the northwest mile after mile of tidal salt marsh with a wealth of wild waterfowl. This is the spiritual home of the Milgate duck punt.

The village of West Mersea occupies the southwest quadrant of the island, and has always lived by whatever the water and marshes could provide, so boats have long been an essential part of daily life. One of the many local businesses was a boatyard once owned by William Wyatt, who, as well as repairing the local fishing smacks and yachts, was also the local punt builder of choice. John Milgate, born in a cottage called Smugglers’ Way, just a few yards from Wyatt’s punt shed, started work at the yard at the age of 13, just after the Second World War. His retirement, 55 years later in 2001, didn’t stop him working on boats; he simply carried on in his own shed at home. The restoration of his 1892 smack, PURITAN OF COLCHESTER, was always going to be a lengthy job, so John wanted a simple, inexpensive boat to get him onto the water quickly, whenever the mood took him. He decided he needed a duck punt.

Gill Moon

Gill MoonSetting the leeward chine deep in the water gives the hull lateral resistance for windward work.

The problem at that time was that no one in West Mersea was building them anymore, so he’d have to come up with his own design, as well as rethink the construction process. The original shape had evolved over the best part of a century and a half, but construction techniques and materials had moved on radically. Many punts were home-built by eye, resulting in a lot of variation. Since many wildfowlers had to contend with shallow pockets, as well as shallow water, they built their punts out of whatever affordable materials happened to be available, and did the building as well as they could. The professionals, though, set higher standards, having good reason to build commissioned punts properly. No one wanted to lie in freezing bilgewater during a hard winter’s night on the marsh, so there was a penalty to pay for a leaky boat. The rule was that if a new punt leaked, its owner was due an amount of beer equal to the water the boat let in.

Professional builders also tended to evolve styles of their own, and the 1919 punt in the Mersea Museum shows that of William Wyatt. Milgate’s study of it revealed a slightly longer hull than some of its contemporaries, but the same 3′ beam. It was built solidly with 9″ x 3/4″ planks and 2-3/4″ of rocker in her otherwise flat bottom. A sheerstrake is clench-nailed onto the side, resulting in a couple of inches more freeboard than in punts from other parts of England’s east coast; this is probably because unlike many of those, it’s an open boat. The other obvious difference is that it isn’t quite double-ended, sporting a small triangular transom above the waterline. The short extended nose at the breasthook has a groove to take the punt-gun barrel. The matte gray finish was no surprise—there’d been plenty of Admiralty-surplus paint available in 1919. Not only was it inexpensive, it was also ideal for making stealthy progress among the mud banks, while stalking highly suspicious ducks. Powder and shot were expensive, so to have a chance of making a profitable bag, getting to within 70 yards of a flock to assure hitting the target was essential.

Marc Davies

Marc DaviesHaving just come about, the punt sailor has dropped his steering oar over the new leeward rail. There is no accommodation for seating other than the cockpit sole.

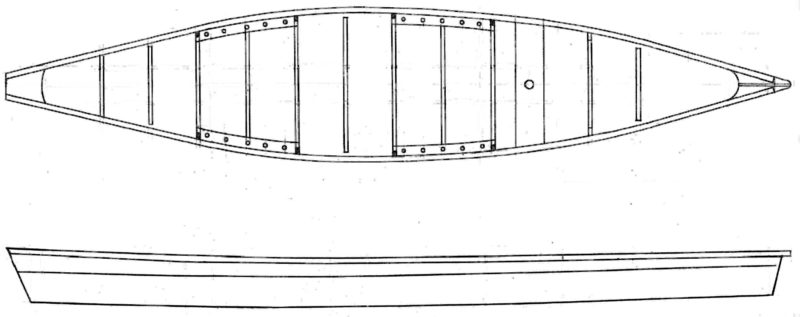

Milgate’s plan was, in the spirit of both the amateur and professional punt builders, to make his new boat as quick and economical to build as possible, while retaining the William Wyatt aesthetic. The 17′ length of the museum’s boat would have been wasteful in terms of plywood, so the new design was shortened to 15′ 8-3/4″, with a beam of 32-1/2″. Milgate’s punt is built with just three sheets of 10mm (3/8″) plywood, using softwood frames in place of the original oak.

The Milgate duck punt could hardly be simpler to build, and architect Mies Van der Rohe, with his guiding principle that “Less is more,” would certainly have approved. There’s no daggerboard, rudder, or decks. It’s just a sleek, flat-bottomed sharpie that’s not quite double-ended. Instead of building the bottom first, adding the stem and sternposts, side panels, and finally the frames, the Milgate design is built upside down on a jig, starting with the side panels. The result of using ply and softwood is that the boat usually comes out rather lighter than a 19th- or 20th-century version, at around 140 lbs, and lighter still if you opt for a stitch-and-glue version. The build isn’t a long process, and many Milgate punt builders are convinced that the majority of the time is taken up by painting.

Marc Davies

Marc DaviesPunts built to the Milgate plans may appear to have two lapped strakes, but each side is made of a single plywood panel. A kerf about 28″ long allows the upper part of the panel to flare to meet the transom. The lap is created by a false sheer strake applied over the side panel.

The fitting-out is equally straightforward. Floorboards are essential unless you’re partial to lying on the frames and soaking up bilgewater. A couple of tholepins, or preferably, in my view, oarlocks for the steering oar are a must-have. A punt rows very well too, so budget for a pair of oars—you can even use the same oarlocks. When it comes to the sailing rig, most West Mersea duck punts use cast-offs from Optimist dinghy racers. The sails you see with the enduringly cool logo of a duck made up of a D and a P are custom-made by Gowan Ocean Sails, about 50 yards from the old Wyatt punt shed. The shed is now part of the facilities owned by the Dabchicks Sailing Club, founded in 1911 by William Wyatt and other West Mersea sailors.

So, now that it’s built, what exactly have we got? Getting to and around the marshes, while occasionally eluding unexpected game keepers, required an adaptable boat that was light to handle ashore, quick to launch, easy to push over mud, and comfortable being sailed, poled, paddled, or rowed. The Milgate Duck Punt is all of these things, as well as a good weight carrier in the bargain; it’ll comfortably take a couple of adults and a fair amount of gear.

Once aboard a duck punt, several things are immediately apparent; the first is just how stable she is, with her flat bottom and low crew position. Next comes the discovery of just how few inches of water are needed to sail her off the beach. Once afloat, a shift of weight to engage the leeward chine and the punt can go to windward. There’s no need to find water deep enough for a centerboard or rudder. Once you’re off the beach, you’ll also discover that the duck punt is no slouch under sail, either.

Marc Davies

Marc DaviesMartin “Lurch” Blackmore makes himself comfortable on the floorboards as he works to weather.

Steering becomes progressively more intuitive, as you get a feel for shifting your weight forward to initiate a gentle luff or aft to bear away, with more major adjustments being done with the short steering oar—usually referred to as a paddle. While this might sound like a case of coarse and fine adjustments, the reality is that you’ll soon be using both methods pretty much at the same time. It’s a bit like steering a bicycle on a winding road by leaning while turning the handlebars. The paddle is key when tacking. Four good strokes, the total allowed under the racing rules, should be more than enough to get the bow around before switching the paddle to the new leeward side for steering.

Duck punts are sailed with the helmsman lying down. There have been experiments with various types of backrest; according to Milgate, the most exotic of these was also the cause of the only recorded capsize. They are usually pretty comfortable for recumbent sailing, and taller skippers, like Martin “Lurch” Blackmore who sails No 10, POINTYBIRD, often stretch out with a leg draped over the side.

Gill Moon

Gill MoonIn the hands of a skilled sailor, a duck punt can take on a stiff breeze.

The Milgate punts can stand up to a bit of weather. In over 20 knots of breeze they’ll be absolutely flying, but still nowhere near the ragged edge. They’re quite maneuverable as well. The close racing in the tight spaces along the foreshore shows that with a bit of practice, the rudder and centerboard won’t be missed.

Aside from breaking out the oars if the wind dies or taking a punt out for a leisurely row on an evening tide after dusk, duck punts are also rowed quite seriously. The West Mersea Town Regatta, an annual event first held in 1838, includes rowing events for duck punts rowed as singles or as pairs.

The duck punt can do anything you’re likely to ask of it in and around thin water. It’s easy, quick, and above all inexpensive to build; the plans are free, and the build itself can be done for about $150. All these things helped convince my wife that I’ve got to have one. The only problem is convincing her that I also need to keep those more complicated and expensive boats that lurk in our garage.![]()

Marc Fovargue-Davies is a Research Associate at the University of London’s Centre for Corporate Governance & Ethics. More importantly, he also works with Adrian Donovan, (who built, among others, his Morbic 12, CADFAEL, as well as a particularly fine pair of Whitehall skiffs), and the International Boatbuilding Training College at Lowestoft, England. Marc regularly contributes to both Water Craft and Classic Sailor.

Milgate Duck Punt Particulars

[table]

Length/14′ 6.75″

Beam/34.75″

Depth amidships/14.125″

[/table]

Plans (5 sheets) for the Milgate Duck Punt are available online.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I have sailed many boats over the years, but none have brought me as much joy as THE DONKEY, my duck punt. For those who are interested in building a duck punt, I have a blog detailing the process of building mine and a large collection of the best Duck Punt sailing videos on my Youtube channel. I can’t encourage you enough to build one! They are inexpensive, lightweight, super fun, and will teach you more about sailing than you think you already know. And where else can you find a boat you can sail in 6″ of water?!

Some of the videos Rusty has collected were created by Martin “Lurch” Blackmore, the skipper of DP 10 seen above. Lurch has a Youtube channel—lurch1e—with videos of duck punts and other boats.

Christopher Cunningham

Editor, Small Boats Monthly

This boat has been “on my radar” for a bit. I think this article just pushed me over the tipping point, and I am going to have to build one now.

I do have one question: what length of oars are used/recommended?

I believe the “class rules” state that your oar be no shorter than below your nose or longer than the top of your head when standing up straight, although there must be a handicap for sailors of diminished stature. I just use a canoe paddle so I would be a laughing stock in Mersea.

Yes, build one!!!

My apologies for taking a while to join the conversation. I’d say that the ethos of the Essex coast in general (and Mersea in particular), is firmly based on what works, rather than any written rules; since “what works” usually includes the question of cost, if you’ve got a canoe paddle handy, no Mersea man would criticize you for not wasting resources on a longer one!

By the way, I spoke to John Milgate this morning, who tells me that his neighbor let off his punt gun yesterday evening, and that various passers by thought that the local power station had blown up. From the perspective of a dozen or so Teal, it might as well have done.