My son was late in arriving. Nine months came and went without any stirrings from him. Another week went by. Still nothing. Cindy and I had both taken leave from work and we had time on our hands, so we loaded up the lapstrake decked canoe I’d built and headed for the lake. We had paddled a mile or so and it was then that Nathan, as he would be named, made his move. Contractions had begun, and not long after putting the canoe back in the garage we were on our way to the hospital. My entry into fatherhood the next day was marked by an unforgettable display of color. Nate arrived after a long and difficult delivery and his skin was a luminescent lilac color. Then, with each of the first breaths he drew, he turned, chameleon-like, a pink so radiant that I thought he’d be too hot to touch. Ten days later, we got Nate back out on the water as a newborn, not in the canoe, but in the Chamberlain gunning dory I’d built for my dad. He was a colicky baby, but was soon sound asleep aboard the boat and didn’t make a peep the whole time.

Two years and 11 months later, his sister was also digging her heels in well past the nine-month mark. Believing we’d discovered that the gentle rocking of a canoe was a sure-fire way to induce labor, we headed for the water again. Sure enough, the first contraction arrived while we were paddling in the middle of the lake. Alison, who has always been much bolder than her brother about approaching new and different experiences, was, as the doctor discovered, already locked and loaded when we got to the hospital. We took our infant Ali out on the gunning dory too. She was born in August, the height of blackberry season, so we rowed around the lake picking the berries that grew along the water’s edge. As we passed by one of the lake’s floating homes, the sight of a swaddled baby brought the lady of the house out on the deck.

“My, so tiny!” she said. “When was that baby born?”

“Yesterday,” we replied.

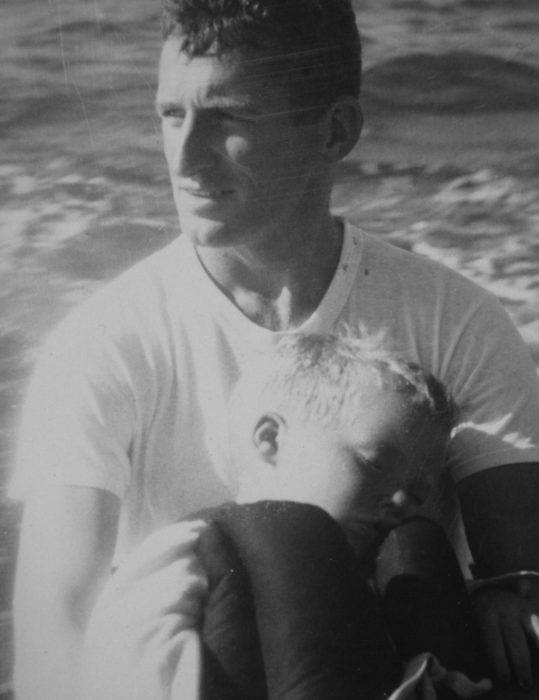

Sound asleep with my father aboard MOLLY MAY, circa 1956

I was too young to remember when my father first took me boating—he is no longer around to tell me—but there is a picture of me wearing a life vest, sleeping against his chest. On the back of that photo, in ink that has faded from black to brown, is written in my father’s hand “sleepy little son.” We were aboard MOLLY MAY, my grandfather’s 31′ cutter, sailing out of Marblehead, Massachusetts, with my grandfather at the helm.

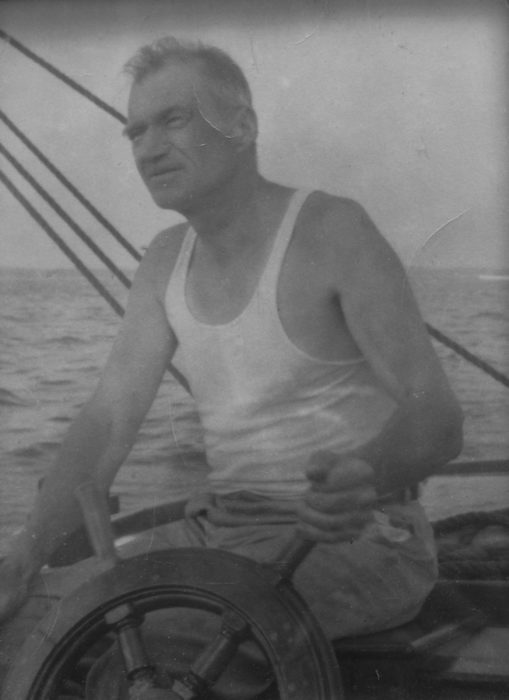

My grandfather, Francis Cunningham Sr., was usually at the helm when we sailed his 31-footer out of Marblehead.

Although I was steeped in boats while I was growing up, I took them for granted. Dad always had one, but I was more interested in riding my bike, climbing trees, skateboarding, and making explosions with firecrackers, calcium carbide, match heads, or homemade black powder.

In 1978, I was 26 years old when I built my first wooden boat, a Marblehead skiff, but it was as a means to an end: travel under my own steam. I was tired of carrying the heavy loads required of long backpacking trips and frightened by the cars and trucks that I had to share the road with while bicycle touring. When I finished the skiff, it met my expectations: it could haul more weight than I could ever carry and could take me places where I had the waterways all to myself. But when I began cruising in it, sleeping at anchor in a snug cove, cradled in the gentle rocking hull, it brought an unexpected and profound sense of comfort and safety. Perhaps it touched upon the sense that all’s right with the world that I felt when I was a child asleep in my father’s arms aboard MOLLY MAY.

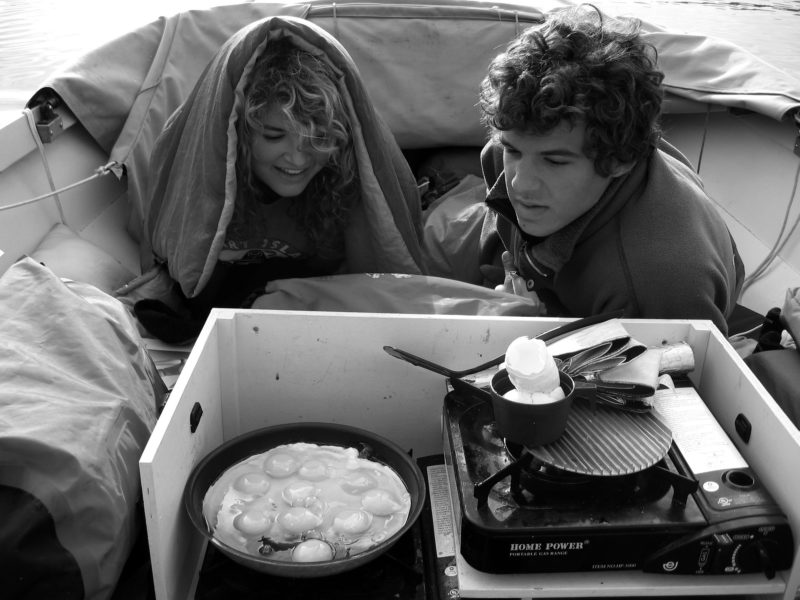

I built a few more boats specifically for voyages I wanted to make, but gradually veered away from building boats to take me somewhere, to building boats that were the somewhere. When I built a Caledonia yawl in 2003, I redesigned the interior around sleeping spaces for my children and myself. Nate and Ali would have a nest forward under a fully enclosed dodger, and I’d sleep on a platform in the main cockpit under a canopy that covered the rest of the boat. For several years we took summer cruises in Puget Sound and the San Juan Islands and never took a tent nor ever slept ashore. Each night we’d drop the anchor, button up the cockpit, and play games until it was time to sleep. I’d often rise up before them and get underway with an easy row along the shore. Nate and Ali would slowly wake to the rhythm of the oars and the sound of water curdling under the laps. I’d get the galley box out and cook them breakfast in bed—scrambled eggs, pancakes, French toast, or scones.

Ali and Nate enjoyed a Dad-cooked breakfast in bed and were happy to spend the better part of the day and night in their nest in the bow of the Caledonia yawl. The dodger that covers them at night is folded forward for the day.

We were never in a rush to shove miles underneath the keel. Whenever we reached a new island, given the choice of going ashore for lunch or eating on the boat, Nate and Ali always opted to stay aboard, where the floorboards yielded underfoot and the benches rocked when you sat down. Nate and Ali cozied themselves in a nest of pillows and sleeping bags, with everything they needed close at hand. The quarters were tight and we had few luxuries, but we were, as Germans so aptly put it, wunschlos glücklich, wishlessly happy.

Is there something innate in all humans that draws us to give ourselves over to the gentle motion of a small boat in the water, just as we are compelled to stare into a fire’s flickering flames? Or is it something that slips into an infant’s heart in unguarded moments in a father’s arms before falling asleep on a boat? Whatever it is, I am drawn to it still, that gentle rocking that soothed me when I was a child and that awakened in my children the urge to be born.![]()

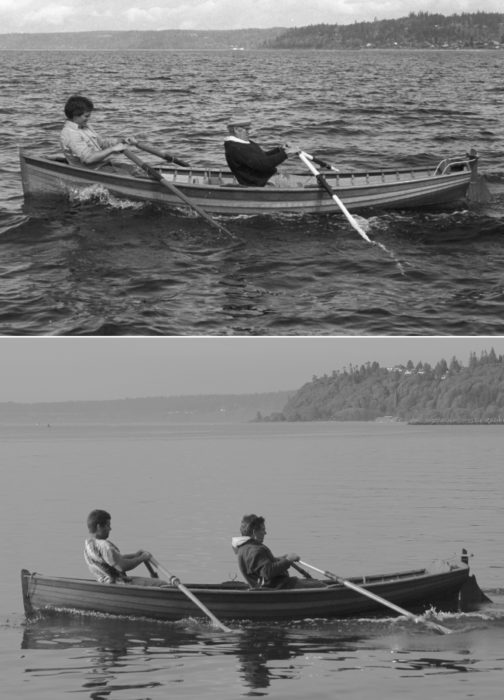

Top: John Hartsock, Bottom: Lily Dickens

Top: John Hartsock, Bottom: Lily DickensWith Father’s Day in mind, my son Nate and I (bottom photo) went for a row in the Whitehall I built in 1983. Thirty-five years had passed since I rowed that boat (top photo) with my father, Frank Cunningham (1922–2013).

Good article, Christopher.

A wonderfully thought-provoking article. I have no way of knowing when Dad first took me out in a small boat, but my own sons all came out with me on salt water when they were under six months old. My first two grandchildren are now seasoned sailors at four and two years of age, both having been afloat on the briny since their first few months out of the womb.

We are now up to the fourth generation of one family to have used the same 15′ sailing dinghy—designed and built by Dad—and there are no signs of any change-of-course on the horizon.

Thanks, Chris

Loved the article Chris. Those are great pictures of you rowing with your Dad and then your son. I also like reading about your Caledonia Yawl camping trips.

As a boy traveling with my family in a car along the south shores of Cape Cod, I saw a sailboat for the first time. Rather than being surprised or intrigued, I remember that it all seemed so familiar. Yes, I thought to myself. I knew what was going on as if I had been sailing for many years. Later that week when I was in a 14′ catboat with my brothers and my dad, I got the chance to hold the mainsheet and the tiller and confirmed that, yes, my hands already knew what to do. I knew how to sail from day one. Later, as a young man, I built a large trimaran and struck off for a two-year adventure with no open-sea experience and no navigation skills. After 10,000 miles under the keel, I returned with body and boat intact, a much different person. But I have often wondered where my connection to the sea came from, I imagine I was a sailor in an earlier life. Whether that is so or not, my connection to the sea runs mysterious and deep as it does for so many others both young and old.

I really enjoyed this article, Chris, so evocative and rich. Many thanks for sharing it.

Wonderful article, Chris! Made me think of my first rowing experience as a young boy, going out at 4 am with my father for fishing. I was rowing silently and he was handling the fishing gear. That was back in the ’50s and we had that beautiful new 13′ 6″ clinker-built larch-on-oak rowboat that my grandmother bought for us. She knew that we did not have the money to buy one; it was a really a gorgeous present because times were hard then and money was scarce!