It’s easy to lose track of time in an attic. None of the things stored in all of the attics I’ve known are needed for daily life and only a few of them, like Christmas decorations, will ever get used. What makes the things stored in attics worth keeping are memories. During summer family vacations in Massachusetts, I spent a lot of time in my grandparents’ attic. Behind a door in one of the upstairs bedrooms was a steep flight of stairs, painted white, that led to what was to me, as a young boy, a cavernous room. It stretched the full length of the house and had a vaulted ceiling, intricate with rafters and collar ties. The stillness of the space and the angled shaft of sunlight from a narrow sash window setting the dusty air aglow made the attic seem like a cathedral. What I remember most about the things stored there was my grandfather’s Army uniform, especially the stiff leather puttees, molded to fit the shape of his calves. It was one of the first things in my life that gave me a sense of history and the value of things that came well before my time.

The attic in my house is not nearly as grand, just a low wedge of space tucked under the roof on the north side of the house. While it is lined with kraft-paper-backed insulation, it is just as much a repository of memorabilia. Many of the cardboard boxes there are filled with photographs—prints from my teens and twenties, and slides for the years since then. There are so many albums, trays, and sleeves full of slides that I keep a light box on the floor, butted against a windowless end wall.

A few days ago, I stooped through the chest-high attic door to find something, I don’t now remember what, and sat down next to the light box. It comes on when I flip the switch for the attic lights, and the clutter of slides on the table gleamed with patches of color, like a crude stained-glass window. I was drawn to a group of warm pale-blue rectangles, slides I had taken during a 2002 kayaking trip to Palau in the Western Pacific.

I set a loupe over one, and as I leaned close and peered in, the tropical island waters and a palm-fringed beach enveloped me, as if I had fallen, like Alice, through a looking glass. I went from slide to slide, then pulled a box of slide sleeves, looking through the hundreds of images I had taken during five days of kayaking there with my friend John. Each look at Palau’s luminous sky and water lifted the weight of this oppressive winter.

Despite its location in the tropics, Palau had its own season of darkness in the fall of 1944. The Japanese held the archipelago and had fortified the islands with artillery and extensive networks of caves. Despite the stronghold’s dubious strategic value in the Pacific Theater, the American Armed Forces launched an attack on the morning of September 15, 1944, the first wave of what became known as the Battle of Peleliu, after the island at the south end of the archipelago. It was supposed to be a quick fight, but it went on for 73 days and cost thousands of lives. The assault was codenamed, prophetically perhaps, Operation Stalemate.

John and I didn’t reach Peleliu, where the worst of the fighting took place, but there were traces of the battle scattered among the islands to the north.

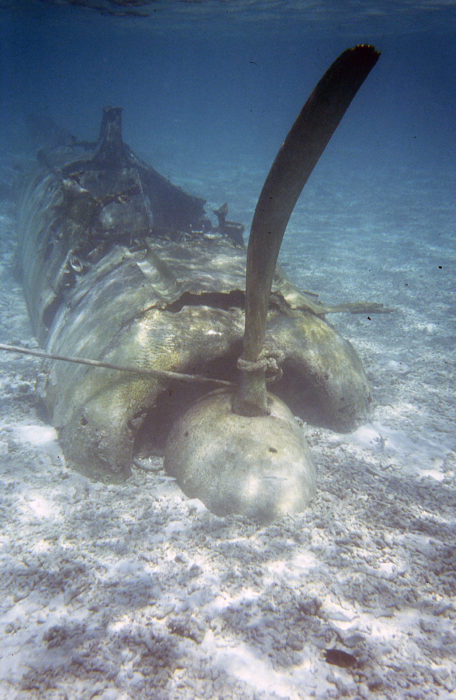

A few hundred yards from one of the islands we camped on, a Japanese fighter plane—a Zero—rests on the Ngaremediu Reef in just 6′ of water. It is upright and the cockpit is open; I sat in the seat once occupied by the pilot when he was shot down.

An engine and propeller blade are all that is visible of another wrecked fighter plane. The tip of the blade was taken by a souvenir collector armed with a hacksaw.

On one of the islands, John and I hike a trail that led past what was once a gun emplacement. Two of the artillery barrels remain, half buried.

Along with the barrels there were several artillery shells.

The trail ended at a lighthouse at the top of the island. The concrete tower was cratered by scores of bullets and, at the top of the lighthouse, an upright on the guardrail had been hit. The steel rod was a thick as my thumb and plowed through as if it were clay. The path the bullet took was very nearly horizontal, so I imagined that an American fighter plane firing 50-caliber machine guns must have been skimming just above the treetops, coming straight for the top of the lighthouse.

A few yards from a well concealed concrete machine gun bunker, dozens of beer bottles were scattered along the trail through the forest. They had been left by the soldiers assigned to guard a narrow passage between islands and now many of the bottles were inextricably wrapped in tree roots.

During the battle, bombing, flamethrowers, and firefights stripped Peleliu bare of its forests, but Peleliu is now as it had been before the war as are all of Palau’s roughly 340 islands. In the half century that had passed by the time John and I visited, the artifacts of war—steel and concrete—had yielded to time and decay and were already being overrun by trees and brush, seaweed and coral. The islands were exceedingly beautiful and peaceful. In the middle of the Rock Islands, John and I landed on Eil Malk Island and hiked a winding trail through dark woods to Jellyfish Lake. Sea water circulates through the island’s porous limestone to refresh the lake and yet the bedrock has isolated the lake from the Pacific Ocean for 12,000 years. The species of jellyfish that now inhabit the lake, having no need to defend themselves, evolved to abandon stinging tentacles. John and I swam underwater surrounded by them, being careful not to disrupt them. The brush of their delicate watery bodies was so soft and smooth as to be almost undetectable.

There was so much to see in Palau from our kayaks, during walks in the woods, and while swimming. The days passed by much too quickly and to sleep seemed like a missed opportunity. I spent a few hours one night walking an exposed reef by moonlight.

John and I paddled two sit-on-top kayaks. This one that John is in was a double and used during passages between campsites to carry our supply of water and a cooler for our food.

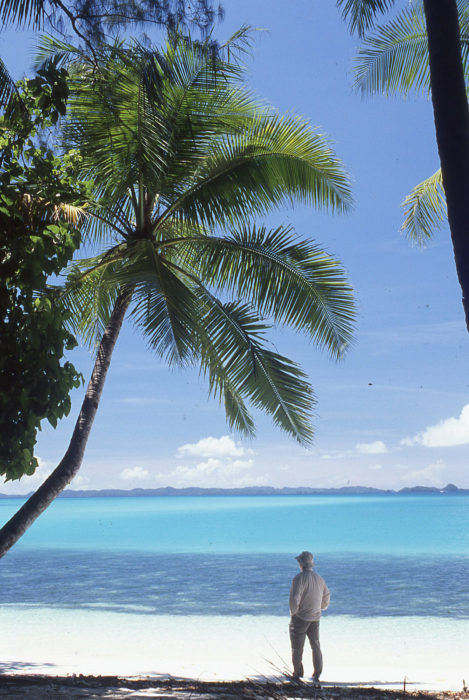

Many of the islands we passed were made inaccessible by mushroom-like overhangs of sharp-edged limestone. Those that had beaches, like this one, provided beautiful places to stop.

In a salt-water pond encircled by one of the small islands we found mudskippers, fish that climb trees.

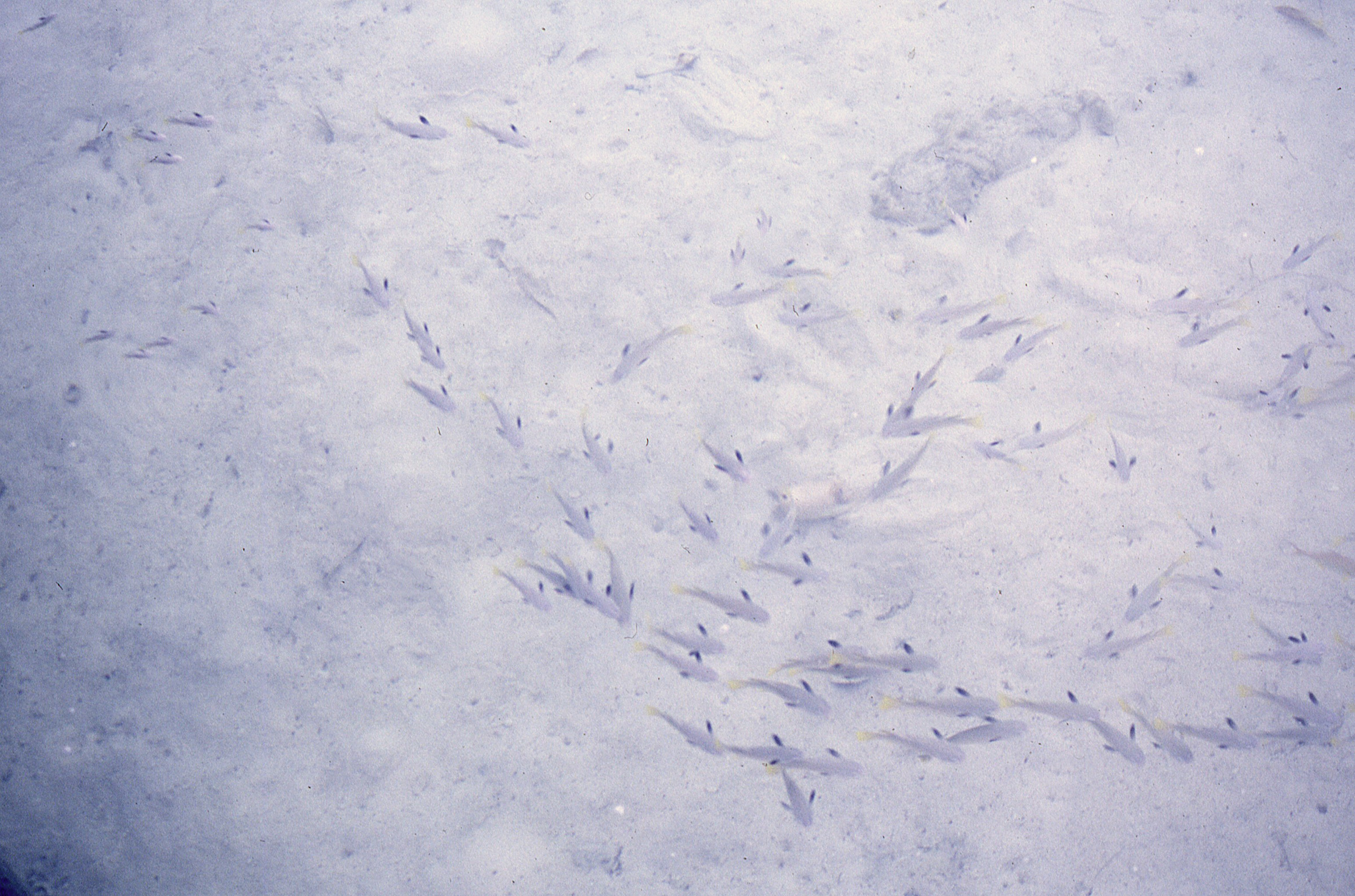

This school of fish made a swirling sumi ink painting in the shallows.

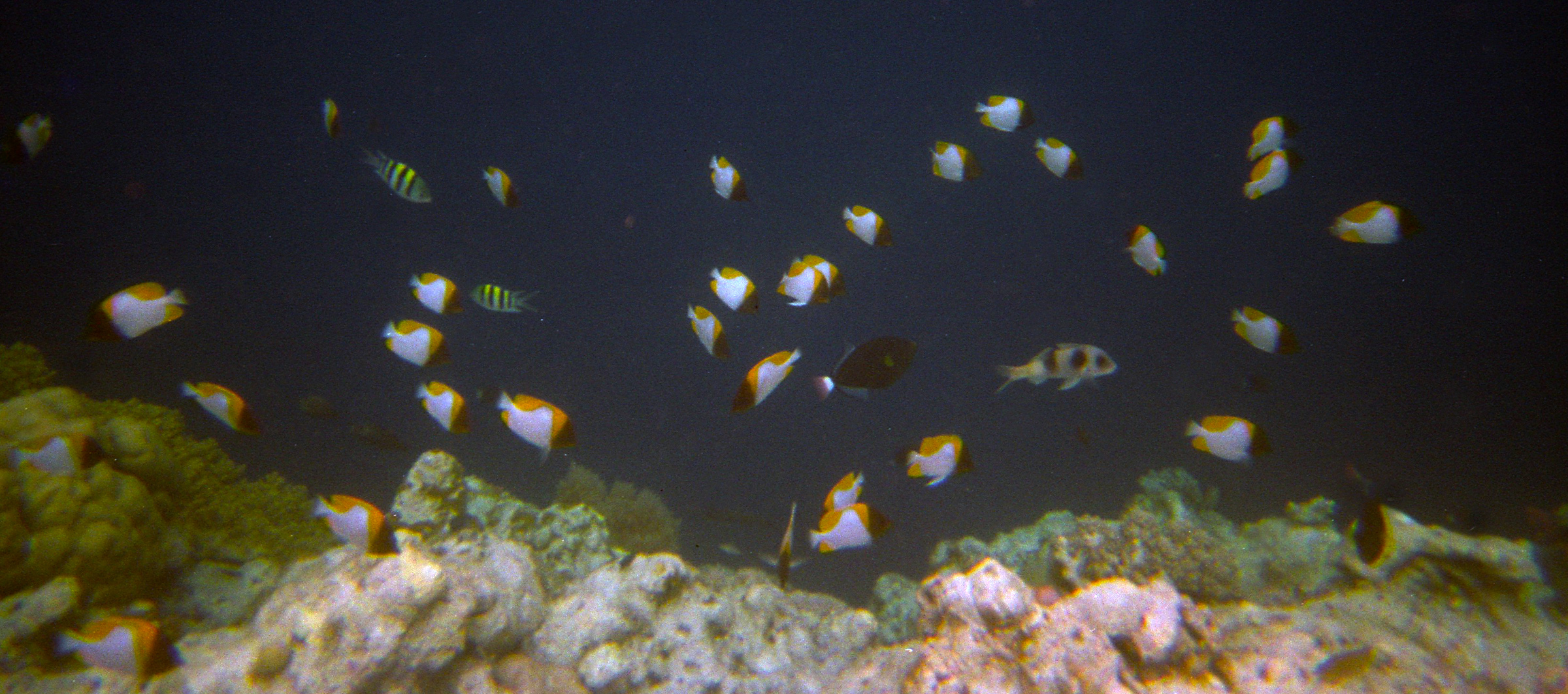

The underwater world was anything but quiet. A loud crackling noise, which sounded like a bowl of Rice Krispies right after milk is poured into the bowl, was made by pistol shrimp snapping their claws. They have one large claw that closes so fast that water cavitates around it. The sound comes from the water imploding back into that empty space. The resulting shock wave stuns their prey.

Fish and coral were almost everywhere in the waters of Palau. There was so much to be seen underwater that we spent almost as much time snorkeling with our kayaks in tow as we did paddling them.

I had come to Palau to write an article, so I always had a pencil and waterproof notebook aboard the kayak. As it became evident that there was so much to see underwater, I began taking notes while snorkeling.

With water as warm as bathwater, it was easy to get off the kayak and explore the shallows on foot.

Most of the mangroves are clustered close to shore with their roots intricately interwoven. These two are striking out on their own at the edge of a vast intertidal sand flat.

This beach where we camped was beautiful by day and even more interesting at night. I woke up to a full moon in the middle of the night, got dressed and walked well over 100 yards on a reef bared by the tide. Many of the tiny tide pools I passed held small fish captive.

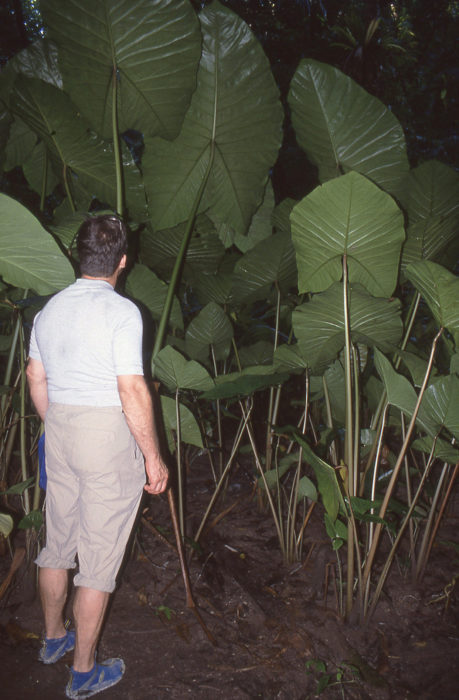

“…and one pill makes you small.” In the woods I found these improbable plants that had leaves up to 3′ long, each on their own stalk, some rising well over 8′ tall.

The broad leaves had an intricate architecture to support them.

In the midst of the woods a single yellow flower grew from the the bark of a tree.

The aptly named St. Andrew’s Cross spiders are kind enough to mark their webs with a large white X, making it easy to avoid walking face first into an otherwise invisible web.

A brief downpour rinsed the salt from our skin and we could sip the cool rain as it trickled down our faces.

Two islets, each only a dozen yards across, were connected by a limestone arch less than 2′ above the water.

On our last day, a 5-mile passage across deep, open water to Carp Island, distance diminished all of the islands to streaks on the horizon. I put on my snorkeling gear, slipped off the kayak, and dove down until I could no longer see the surface, only the same bright blue in every direction, with nothing to indicate up, down, or distance.

The slides in my attic, aside from briefly transporting me to a different, exceptionally pleasant time and place in my own life, brought some comfort in a winter whose long shadows have been further darkened by a pandemic and political strife. A broader view of history, offered by the woods and waters of Palau, holds a promise that, in time, enemies can become allies and battlefields paradise.![]()

Thanks for taking us along on a much needed break from this troubled season. Beautiful photos and a nicely documented tale.

Great wintertime story!

Good thing that shell decided not to fragment. Back when I was in EOD we tripped regularly to the Pacific to deal with unexploded munitions. People would gather or mark them.

I read your editor’s note in the March issue and it brought back similar memories of a grandfather’s attic, the real kind of attic. It contained my father’s uniform and a series of model planes he built while recovering there. I remember in particular a model of the fuselage of a DC-2, complete with interior details.

But what I remember most is the smell. Part wood, part musty, some leather, etc. I’ve come close to smelling that again, but never the exact aroma. They say that smell memory is very powerful. I believe them.

Thanks for sharing your memories and photos of your trip. I, too, am glad that the shell didn’t explode. And the war grave site of the aircraft must have been very moving.

Nice!