"Don’t you think such a project is a little too big for you?” That’s what my father said when I told him I was thinking about building a kayak. He used to do little craft projects with me when I was younger, and I remember when we made a small wooden figurine for Grandma to put in her garden. He did the sawing out and let little me do the painting. While he had in mind teaching me to use some tools and different materials, in the end, he always did the building and all the work with the tools, while I watched and cleaned up afterward. When I was old enough, I stopped taking part in these projects and turned to some simpler craft projects I could do on my own, such as sewing, braiding, and working with leather.

“A little too big” came back to me as I stood in a lumberyard collecting the first of the materials for building a Greenland skin-on-frame kayak, but the echoes of my father’s words faded as I breathed in the wonderful fragrance of the wood surrounding me. Thomas Bruns came out of his storehouse carrying a very long packet of lumber. He is the father of an old friend of mine, and I’d recently found out, just by chance, that he’s a lumber wholesaler. I could not really believe my luck, because for weeks I had searched the Internet for a source of wood of 16′ or more in length, knot-free and straight grained. Thomas had been very friendly when I emailed him, offering me wood for my project and not wanting any money for it—the amount of wood I needed for my kayak was not a quantity they think twice about giving away. For two big boards of pine and four beautiful, knot-free 20′ boards of hemlock I paid one homemade chocolate cake.

As I strapped the boards to the roof rack of my parents’ car, I still could not believe I was doing this. These boards were longer than any kayak I had ever handled, and “too big for you” was suddenly something I could see and struggle with as I loaded them.

The idea for this building project came up when I was practicing Greenland rolling in pool sessions during the winter months with my fiberglass Greenland-style sea kayak, christened NAAJA. In the Greenland tradition there are rolling techniques for every eventuality. In the Greenland National Kayaking Championship there are 33 different rolling techniques, from the Standard Greenland Roll with a paddle, to the Straitjacket Roll without a paddle, arms held tightly across the chest. I love my kayak, but it is just not perfect for rolling. I needed another kayak, one meant for rolling.

There are only a few manufactured models available that would fit for me, as I am not very big—5′ 7″, around 130 lbs—and a boat for rolling should be very low in volume. Suitable boats turn up only rarely in Germany as used boats, and shipping a new one is too expensive for some playing around in pool sessions. My boyfriend Martin said “just build one for yourself. It can’t be that difficult.” He was not really being serious, but still, the idea stuck with me. Then I started reading everything I could get from the Internet, and finally ordered the book Building the Greenland Kayak by Christopher Cunningham. I read through the whole book in a few days.

With every page I read, I tried to imagine if I could do each step, if I had or could borrow the tools I needed, and so on. As I got more and more interested in the idea of building, my thoughts drifted to it no matter where I was or what I was doing; I even had a dream about it. As I read and planned, it slowly became clear to me that the process of building the kayak was not that difficult. I became more and more determined to take the project on.

My parents did not take me very seriously at first, and I tried not to bother them as they had already been complaining “you only ever talk about kayaks,” even before this project got stuck in my head. I was used to this. For the last 15 years before I took up paddling they complained I “only ever talked about horses.”

I discussed everything with my boyfriend, but even he grew tired of the topic at some point, even though he was the one who got me to take up kayaking three years before. He is still making fun of me that I took it up a bit too well, laughing at my ever-growing collection of kayaks and gear and list of places I want to paddle. He also taught me paddling and rolling in the first place, and my first kayak was given to me by his grandpa.

I plotted where I could get my materials and find some space for building. When to do it was clear: I was to finish my master’s thesis in microbiology/biochemistry by the end of March 2019, and would start a PhD program on the first of June. I looked forward to building with my own hands something I could actually use. It would be just the break needed from lab work and sitting in front of computers trying to make sense of weird measurements of microscopic bacteria.

I needed a place to build the kayak. I was living with my parents in a flat on the third floor, and our cellar was so small that there wasn’t even room for my bike. I would have moved out earlier, but I wanted to wait until my boyfriend and I both had jobs and knew we would not have to move farther away within the next few years.

As I earned a lot of skeptical looks from family and friends alike for my project, I got more and more determined to do it. I did not expect it to come out perfectly, but I wanted to prove, not just to them but to myself, that I could do it and do it on my own. The biggest projects I’d done were a leather book bag and two leather guitar straps—nothing like building a whole boat from scratch. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that proving what I was capable of was driving me more than any need for another kayak, but I would never admit that to anyone.

Photographs by and courtesy of the author

Photographs by and courtesy of the authorRalf-Peter’s workshop is amazing, but not a place to visit if you are claustrophobic. It is filled to the ceiling with boats, wood, and other materials, as well as all kinds of machines. To get from one end of the shop to the other is an exercise in acrobatics because you have to climb over and duck under boats and stacks of wood, and there is scarcely any bare floor.

Even before I set up a workplace to build the kayak, I needed to get my stack of boards sawn to the dimensions required. This necessitated a tablesaw, a machine I had never used before, and was the only step I was willing to accept help with. My friend Ralf-Peter Stumme has a prehistoric tablesaw with no safety features at all; I am always amazed that after using that thing for years he still has five fingers on both hands. He would not let me use it anyway, but he would do the rip sawing for me.

I rounded the corner into the yard of the rowing club in my hometown of Mülheim, Germany, where Ralf-Peter has his workshop, and heard a radio blasting some audiobook from the station he is always listening to, and I saw him in his customary red-and-white striped shirt working on a century-old four-oared racing skiff. The red and white stripes are the “official outfit” of the Classic Boat Club he founded in 2004, and about the only color of clothing Ralf-Peter owns.

As we unloaded the boards from the car roof rack, we chatted a little about my project. I was really happy to finally talk to someone who actually knows something about boatbuilding and who was interested in my plans.

Ralf-Peter put my boards through the tablesaw and I, at a safe distance from the blade, supported the boards as they came off the saw. We milled two gunwales, two chines, and a keelson for my kayak. After we loaded the milled pieces back on the car, I paid Ralf-Peter with a chocolate cake.

During the previous weeks of planning, I had figured out the perfect, secluded place to build my boat: my grandma’s garage. It is not very big, but if I kept the door that connects the garage to her garden shed open, there would be just enough space for an 18’ kayak and some tools. I had tidied up and moved out old flower pots, garden furniture nobody needed, and bits left over from projects my grandpa had done decades ago.

The space was small, but I’d have it mostly to myself and be free to make every mistake on my own. I trusted my grandma would not get involved too much, unlike my father or some people from our paddling club. I had a very good connection to my grandma ever since I was a small child. Her name is Ingrid, but I always called her Lieblings Oma— “Favorite Grandma” in German— when I was little, and only when I grew a little older did I learn that this was not very nice for the other grandma, so I just called her Ingrid or Oma. I would spend a lot of time in my late granddad’s little workshop as a child and was allowed to use some of the tools that he had left in the cellar. As I grew up, Ingrid would be the only person to witness my budding skills and trust me enough to let me do useful things, like install a ceiling lamp in her living room and doing minor repairs around the house.

Working at my grandma’s place had another great advantage: every day around noon, that good soul appeared in the dusty doorway to my wooden cave and called for lunch. A few hours later, there was cake. Or ice cream. Or both.

As lovely as this was most of the time, it became a kind of stress factor over the time I worked there. One day, while I was painting the frame, with my hands full of sticky boat oil, she could not accept that I did not, and could not, eat anything right then. She ended up standing directly next to me and shoving bites of ice cream into my mouth while I kept working. I accepted this to keep her happy, even though it really got on my nerves. Except from these minor occasions where I was stressed because of varnish needing my attention or steamed wood ready to be bent, we got along very well and I think she enjoyed having me there.

The first jig I made for the kayak project was a drill guide for drilling rib mortises into the gunwales. I nailed it together from some scrap wood I found in my granddad’s cellar. I didn’t focus on the aesthetics very much, but it still worked well. Over the course of the project, the contrast between this early piece and later parts became ever more apparent as my woodworking improved.

I quickly got into a routine of reading the book in the evening on the couch at home to memorize the next step I wanted to work on the next day. Then I converted all imperial measurements into meters and centimeters, looked up a few specific terms I didn’t know (English is not my first language), and put down some notes in German to use while working. This prevented a lot of time from being wasted while working in the shop.

As I shaped the gunwales, I built a few jigs to help with marking all necessary mortises and drilling holes in the correct angle and make it more efficient and precise. After about a week, they were ready to put on the building forms that would hold them in their proper angle and shape. This sounds easier than it was. As soon as one end of both gunwales was put into a form, the other end sprung apart, adding to the chaos in the crowded garage. After a few attempts I asked Grandma to help me and hold one end while I worked on the other. Together we finally managed to put the forms on. With just the gunwales sprung around them, what I had made already was looking like a kayak.

I’d been struggling with putting the building forms on the gunwales, but when Grandma happened to come by to see what I was doing, she lent a hand and held the ends of the gunwales in place.

Oma is way over 80, with age-worn bones and joints that barely allow her to walk properly, but she would never refuse an opportunity to help me with minor things on the kayak. She would look very content to be part of the project and was at least as proud of the boat as I was, but never trusted it would be seaworthy. She had been afraid of the water her whole life, and never learned to swim, so she expected the river would swallow me and the boat the first time I slipped into the cockpit. I tried to convince her it would stay afloat, or at least sink slowly enough for me to get out, but I don’t think she ever believed me.

The trunnels that keep the gunwale ends together have kerfs flared by wedges, so they cannot be pulled out when the kayak frame flexes. They’ll be sawn flush with the gunwales. At first, I struggled with the wedges because I made them too small and they broke off when I tried to hammer them into the kerfs, but when I made them from ash instead of pine and with a thicker tip, they held up very well. I was amazed by the fastening. It is cheap and elegant, requires very few tools, is super easy to do, and yet it is a very strong connection.

The weeks followed the same routine: I’d have breakfast with my parents before they left for work, drive to my little boatshop, work on the kayak for a few hours, have lunch with Grandma, work some more, have some cake or dessert, and then go home to do some paddling, horseback riding, or play my saxophone.

Every morning, I arrived to find my kayak lying there, waiting for me. The garage was fragrant with wood, reminding me of when my dad took me shopping for wood when I was little. Even the shop floor, littered with shavings and wood dust, had its own bouquet.

Each stem piece is fastened to the ends of the gunwales by lashings. They start with the turns of artificial sinew making a V shape between three holes. Turns around the two arms of the V to pinch it into a Y shape greatly increase the tension. The lashing is angled across the joint to pull the stem tight to the gunwale ends. The keelson, at top, will get pegged to the stem with the pegs set at different angles to lock the keelson in place.

When I opened the door to the garage, sunlight gave it a nice golden glow and the warm spring air and the songs of birds filled the space. As the weather grew warmer, the garden behind the garage came alive. It was full of flowers of every kind and color, but especially roses, which my grandma loves most. Some of them are much older than I am—they were planted by Ingrid’s mother. She is a good gardener and spends almost every day in her garden. Nearly every week, there are new flowers blooming somewhere. Among the flower beds there are herbs for cooking and a little grassy lawn to just lie upon and watch clouds drifting across a blue sky.

As spring warmed toward summer and I worked with the garage door open, I became entertainment for the neighbors. Little Emilia, who lived next door, was at first afraid of me and my electric sander because it is so loud, but when I switched it off, she was too curious to stay outside any longer. Sitting in the half-finished frame and using a little broom as a paddle, she laughed so loud that her older brothers came over to see what all the fun was about.

My grandma also did her part spreading the rumors about the girl building a boat in a garage, giving tours of the shop and showing the kayak to everybody who came to visit, but only after I went home for the day, because she knew I did not want the attention while I was working. She even showed it to a handyman who had come to the house to repair a broken window blind. After he saw the kayak and admired the work I’d done he said, “And this was really built by a woman?” Grandma was still very angry about that comment when she told me about it the next day.

When the deck part of the frame was finished, I put it to a test by resting it on the work stands and sitting on the deckbeam just aft of the cockpit, the one that will later be the backrest while paddling. I was amazed by how sturdy the structure was already—it did not bend or flex when I set my full weight on it.

The nine straight deckbeams and the two arched deckbeams forward of the cockpit were attached with pegs angled through the gunwales; the ends of the gunwales were joined with trunnels and lashings. As someone who has never worked with wood before, I was amazed how strong and stable the delicate-looking framework was at this point, even if it was just the deck and the whole hull was still missing. Resting on two work stands, it could support my full weight without any significant flex.

The hull consists of ribs made from ash and steam-bent to achieve the shape of the hull. Before bending, the ribs needed to soak in water for a while. After a lot of looking around, the only fitting container I found was the old bathtub in the cellar, dating back from when the house was still divided into two separate flats and my great-granddad had his bathroom in the cellar.

Steaming and making the bends was the step I was most afraid of and thought was most likely to go wrong. Just in case, I ordered more wood than necessary to have some backup. I made the steambox out of Styrofoam and attached a steam generator meant for removing wallpaper. When it was fired up, the workshop smelled and felt like a sauna: hot, wet, and fragrant from the heated wood.

Looking from the foredeck area toward the stern, I checked the ribs for symmetry. The deckbeam in the foreground is the one that will serve as the foot brace.

Steaming the ribs for the first time was a stressful task. The ribs are in danger of breaking, and I could scald my fingers. This was not the time for me to answer questions or have someone getting in the way. Oma—always interested in what I was doing and eager to hear that the next steps of the construction would be—stood between the kayak and my steambox, asking way too many questions while I was intensely focused on bending the wood. As I was doing it for the first time, I was not sure how important it was to stick to the steaming time exactly, and I did not want to take any chances. As soon as the wood is out of the steambox, it starts to cool and dry and becomes inflexible, so it needs to be bent without delay. This was the only time I ever had to throw Oma out of her own garage. I could tell she was a bit offended, so I explained the problem to her later and showed her all the parts I’d bent. That reconciled the two of us (well, mostly). I had to eat an excessive amount of ice cream afterward to finish making amends. After the ribs were all in their mortises in the gunwales and secured with lashings to keep them in place, I lashed the chines and keelson to them. I was amazed by the simplicity and the ingenuity of traditional Inuit boat building: pieces hand-hewn from driftwood, all held together with pegs and lashings. A few simple hand tools and materials gathered from the land produced seaworthy boats with such beautiful lines.

There wasn’t enough space in the garage to work on the stems, so I put the kayak frame out on the driveway and set it on cardboard boxes. I clamped each rough-cut stem to the gunwales several times to check its shape, and then did some adjustments until I liked the lines. Ingrid often came outside to see what I was doing and, with the boat sitting outside the front door, she could perch comfortably on her steps and watch my progress.

The last parts of the hull to make were stems, which I cut out of the pine boards Thomas gave me. They were lashed to the gunwales and attached to the keel by pegs. The ends of the chines were beveled and then pinched to the stems by a lashing that allows them to give a bit to dissipate impacts and accommodate the flexing of the kayak in rough water.

When all of the ribs were in place, the hull started to show its shape, so I brought it outside to try it on for size.

I made some minor changes to the stem shapes described in the book, just to fit my personal taste and the kind of kayak I wanted to build. I worried a bit about changing the paddling characteristics, as I knew there are many complex connections between shape of the kayak and its speed, maneuverability, and seaworthiness. A rolling kayak should have a minimal volume—the lower it sits in the water, the easier it is to roll—and I did not want to compromise the paddling and rolling properties too much, so I made only small changes.

The deckbeam that I’d brace my legs against is called the masik in Greenlandic. It had to be high enough to allow me to slip in and out of the cockpit and low enough to provide for a solid connection to the kayak.

When I sat in the kayak to test the fit of the cardboard masik template, I would have preferred to sit in the garden with the boat, but on that day it was raining. I read a book to keep myself entertained while I made sure that I could sit in the kayak for a while without my legs hurting or going numb. I had left the garage door open and, when I heard people walking by, I turned around and was often met by curious stares.

To find out a perfect shape for my masik, I cut out a cardboard test pattern and clamped it to the gunwales to see if I could get in and out of the boat and sit in it comfortably as well. To test the long-term comfort, I sat in my boat, on the floor of the garage, and read a book for an hour. This attracted even more long stares from the people walking their dogs or on their way to the bus stop. Many of them I did not know—they probably lived a few streets away—and they passed without stopping, so I didn’t get to explain why I was sitting in my kayak with a book.

When I was fitting the masik, the aft deck ridges were already in place behind it. Here, the arched deckbeam forward of the masik is not yet in place. This will give the forward deck ridges a nice curve from the straight footrest deckbeam to the masik.

After adjusting the cardboard masik until I was happy with it, I traced its outline on a 2″-thick ash board and cut it out with a sabersaw. After I pegged it in place around the top inside corners of the gunwales, I attached the deck ridges just forward of the masik as well as the pair aft of the cockpit. The frame was finished. The weather was very nice and I gave my boat a little photo shoot in the garden before covering it with its skin, concealing the elegant structure for the next ten to twenty years.

There were so many flowers and shrubs in my grandma’s garden that there wasn’t room to photograph the finished frame without damaging the plants or having them in the way. Her neighbors are not as keen on flowers as she is, so I used their garden as a photo-shoot setting with more space.

With the frame finished, I decided it was time to give the kayak a name. I wanted a Greenlandic name, with a meaning that matches the boat. After some research and a lot of reading through various online dictionaries I finally settled for alleq, the Greenlandic word for the long-tailed duck—Clangula hyemalis—a species common in the Arctic and famous for being very vocal. That made it a good match for me—as a child I was often scolded for talking too much.

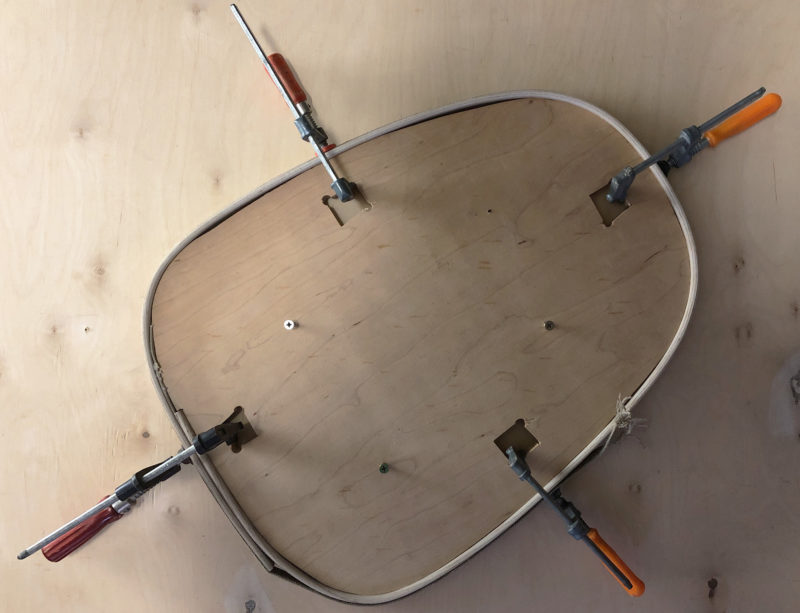

After steam-bending the cockpit coaming around its form, I set it out to cool and dry overnight. On the next day, the hoop held its shape very well and I would bend the coaming flange over it.

While the frame was complete, there was only one more wooden part to make, and that was one I was kind of afraid of: the cockpit coaming. It is a wooden steam-bent hoop and it would be attached only to the kayak’s skin. I’d had some splits develop when I was bending the ribs, so I made the stock for the cockpit hoop thinner. That worked quite well. I used thicker stock to make the coaming flange, which would hold the spray skirt. It failed when bending so I ended up making it in two separate pieces, joined with glued scarf joints. The end result had an acceptable shape and was pretty strong.

I gave the frame and the coaming three coats of boat oil, a mixture of boiled linseed oil, tung oil, and other natural oils. Its smell was not unpleasant but it carried a few hundred yards down the road, leaving the whole neighborhood smelling like a boatbuilder’s workshop. I often noticed people passing by with their noses up in the air, sniffing to figure out where the smell was coming from.

With all woodworking done, it was time to sew the skin on. ALLEQ’s skin is made from cotton duck, which would later be painted with oil-based boat varnish to make it strong and waterproof. To get the skin on without having wrinkles on the finished boat, I waited for a very hot and sunny day, because cotton canvas can’t be fully stretched when it has moisture in its fibers. It takes two working together to get the skin pulled really tight—one to pull the canvas tight and the other to staple it, temporarily, to the gunwales—so, for the first and only time during my build, I asked Martin to help me.

I was so nervous and excited when we arrived to do the work on my grandma’s terrace. I warned her that we wouldn’t be able to stop in the middle of the process, so she brought her armchair and cup of coffee outside and settled in to watch us in silence. In the glaring sun, with the temperature climbing into the 80s, I felt a little sick when Martin and I started to work.

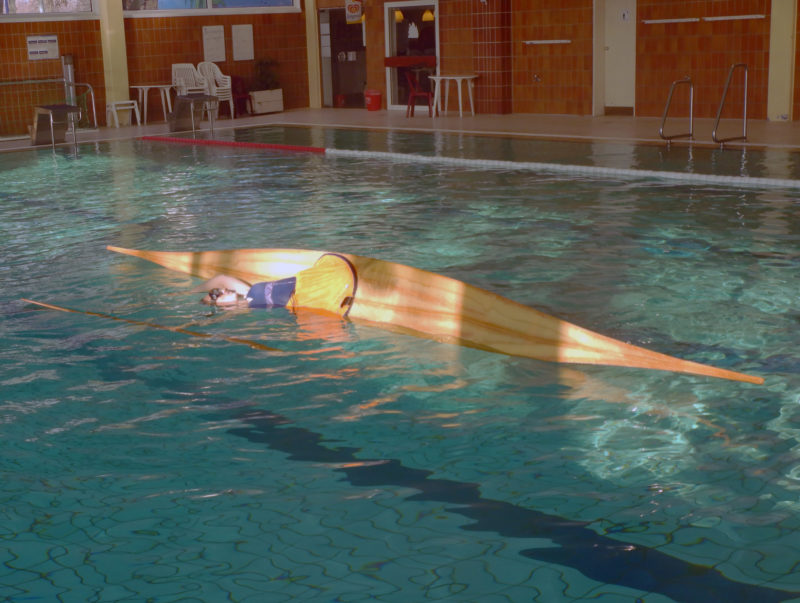

Getting the canvas skin on the frame pulled really tight requires two people and some strange contortions. To pull the longitudinal tension into the skin, Martin laid on his back with the stem on his chest, braced his feet against a deckbeam, and pulled the canvas while I stapled it to the stem. Here, he gathers his strength for the big pull.

Finding a good position to pull the skin tight on the frame of the kayak led to a few funny positions, but Martin is used to crazy jobs from working in Ralf-Peter’s workshop as a student and did not complain. Ingrid stayed in her armchair all day, sometimes smiling or grimacing as she watched us struggle, and wisely kept her thoughts to herself.

We managed to stretch the skin over the hull, holding the tension with a neat row of staples along the sheer, and sewed half the deck by evening. Sewing up the rest and removing the staples took me another two days, but I could easily do that alone. The cockpit coaming was attached to the skin by sewing as well, resting its forward end on the masik, and the aft end steadied by the two aft deck ridges.

Sewing the canvas skin under the hot summer sun was not very pleasant, but Ingrid thoughtfully lent us her little parasol to make the work a bit more tolerable. She also served up lots of ice cream and cold drinks, so it could have been a lot worse.

When all sewing was finished and ALLEQ already looked ready to go, the time-consuming process of coating the skin started. I wanted to do it with the natural oil-based varnish, to avoid any harsh chemicals and having to wear breathing protection while working. This meant having to put on several layers of varnish, each of which needed to dry for at least 12 hours before I could paint the next layer. As the boat always had contact with the stands I placed it on, I could only paint either the hull or the deck each day.

The whole building project had gone on much longer than I had planned: I had started working on my PhD project full-time in June, and the kayak’s progress was slowed down as I was only able to work on it on weekends and some afternoons.

Summer slowly faded into autumn, the days grew shorter, the weather got colder, and I slowly became tired of a routine of work–varnish–eat–repeat. In the end, I went to the garage every day to sand the varnished surface and then brush on another layer not because I enjoyed doing it, but because I wanted to get it over with. Grandma had started to worry about where she could put her garden furniture over the winter if my kayak was not finished—another reason to pull through and get it out of that garage.

The varnishing went on for three weeks and I finally finished it in time for our kayak club’s end-of-season paddle at the beginning of October, roughly five months after starting the project.

After taking the finished kayak to our club’s boathouse, I wanted to take the usual look-what-I-built photo. My friends laughed at me as I posed, but they obliged and took the picture for me.

From the beginning, I was looking forward to bringing ALLEQ to the club without any announcement beforehand, to enjoy the surprise on people’s faces. On the day of the tour, I took the car with the roof rack to my grandma’s house and loaded up the boat with a little help from Martin. Then we drove ALLEQ over to the club slightly early, placed the gleaming amber kayak on the grass in front of the boathouse, and waited. Two more friends arrived who knew what was going on, so there were four of us, standing in the doorway, giggling, and brimming with excitement.

My plan was fulfilled: people stopped, looked a little confused, and started searching around for whoever placed the kayak there. There were lots of questions and even more compliments. Some people did not even realize the boat was self-built and thought it was bought somewhere. I was really happy to answer all questions and…I enjoyed the attention. I had kept quiet about the project all along, to make this moment even more fun and special. Now I enjoyed it as best as I could.

When everybody was ready to go, we finally took ALLEQ down to the river Ruhr. Getting aboard was a little bit tricky as expected, but worked out fine and I stayed upright and dry. Finally paddling my boat, I could not get my huge grin off my face: ALLEQ paddles very nicely, is very maneuverable, and is faster than I had imagined. Unfortunately, Ingrid could not be there on the day, as it would be too far for her to walk from the parking area to the water to see us depart, but I took lots of pictures for her and promised I would find a place where she can watch me paddling ALLEQ without having to walk far.

ALLEQ looks good on the water, very sleek and elegant, and, when I’m aboard, rests perfectly in the water with just enough freeboard. Sitting on the bare wood slats is much more comfortable than I had anticipated. I had planned on putting in a seat cushion later, but that does not seem necessary. I did, however, add a piece of pool noodle around the coaming as a backrest.

When I took ALLEQ to the swimming pool for the first time, I was really happy about the rolling I could do. In this picture, I’m doing a balance brace, a way of floating on your side, halfway between capsized and upright. The paddle, held on an extended arm, provides extra flotation. Properly done, this position can be held with little effort and nearly endlessly (or at least until you get hungry).

The weekend following the launch, I took ALLEQ to a pool session for kayaks, and it again fulfilled my expectations. It rolls better than my sea kayak and its masik gives me a very good connection; I could easily complete some rolls that were difficult before. For the first part of the session I was so busy answering questions that I barely had the time for rolling. Everyone at the pool was surprised by the kayak from the moment it arrived. There was an endless stream of compliments.

Martin and his father both were eager to try the kayak, but it was built to fit me and was too small for them to slide into the cockpit even though they can easily fit and paddle all my other kayaks. Neither of them is that much bigger or heavier than I am, but their feet are at least two sizes bigger, and that is enough to form two bumps in the deck when they try to slip into the cockpit. My parents were not very interested in the kayak, and did not see it launched and paddled, but they happily listened to my report about the event the next day. I am pretty sure that they are secretly proud of my work and that I achieved it all alone, especially my dad, but he would never tell me.

For myself, I am very happy with the outcome of the project I had taken on and seen through. I had feared that there would be visible flaws on the finished boat and that the kayak would not paddle with the modifications I had made to improve its rolling ability. The project was a huge success, and gave me a lot of confidence in my abilities. I am a little worried about being overconfident, but I believe future projects, like making a Greenland paddle for ALLEQ, will work out if I just take the time and try.

Martin got a new job and we were able to move into a new home of our own. It needed some work and, when we began to remodel the kitchen, I was suddenly responsible for all the sawing, because Martin said I was the one with the skills required. He cannot have been entirely wrong, because all of the countertops fit quite well, and our new kitchen is working just fine.![]()

Isabelle Heker lives in Essen in the Ruhr area of western Germany. She is currently working at the University Duisburg-Essen in the laboratory and writing her PhD thesis in microbiology/biochemistry. She was introduced to paddling by Martin about four years ago, and since then accumulated a collection of eight kayaks and two canoes. Paddling soon took up an increasing part of her life, with membership in a club, paddling holidays and tours, and organizing and instructing paddling courses for the university’s sports program. The Greenland-style kayak, ALLEQ, was her first attempt at boatbuilding. She had no previous experience in woodworking, but used to repair fiberglass boats with Martin sometimes when necessary. When she is not paddling or working, she is horseback riding or playing saxophone in a Big Band.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Wonderful memories with Oma

Isabelle, best Small Boats article, ever!

Isabelle, you rock!!! Having previously build three wooden kayaks, two in Greenland style, I just recently finished a skin-on-frame West-Greenland boat which looks very similar to yours, except of course, made to fit me. Despite the previous building experiences, I thought of the SOF build process as a special challenge, albeit one that would get me closer to the roots of kayaking and rolling. Yes, the bending of the ribs was particularly unnerving given the short time-window to get the correct curvature which changes from rib to rib. I am super-impressed with your courage and persistence and I suspect that this may not be your last venture into boat building.

As someone who was raised in Germany I read with a tinge of sorrow that your father did not express his appreciation and admiration of his daughter’s astonishing accomplishment. It seems to be a particularly prevalent characteristic of German parents (especially fathers) to not be able to compliment the achievements of their offspring. Perhaps a new generation of parents will overcome such sad inhibition.

Anyway, the water is very crunchy around Western Pennsylvania, so I’ll have to be patient in trying out my new SOF kayak. Meanwhile, I so enjoyed your beautifully-written account.

First, congratulations to Isabelle – great boat, exceptionally well done! I envy you for the great building experience as well as for the outcome!!

Christoph – I’m a bit shocked by your very generic and categorical statement about German parents: “It seems to be a particularly prevalent characteristic of German parents (especially fathers) to not be able to compliment the achievements of their offspring” – Wow! That’s pretty strong, if not outright offensive. This does not at all correspond to my experiences of growing up or being a father in Germany. In Germany, like in probably all other countries around the world, there certainly are parents with one or other deficiency (or even too many thereof), but “a particularly prevalent characteristic”… come on…

I know, this is not the place for discussions other than boating, but as a caring father, I cannot let this stand uncommented.

Peter

Congratulations not only for starting on something you weren’t sure about but persevering through to the finish!

All of us who build our own boats had to start with a first boat and we had to learn the skills and develop solutions to problems just the way you did.

Great story!

Great article, well written, and good sense of humor. So much ice cream!

Thanks, Isabelle, for a terrific article. The story, the kayak, and most importantly, you come through beautifully in your writing. Please write more articles for Small Boats as life and paddling go on! And best wishes for a successful Ph.D.!

Regards,

Tim

Very nicely done! That’s a superb looking kayak, especially for your first attempt!

I loved your story. Capable people can do many things. I’m planning my small-boat building experience, and think SOF will be my launching point. I have more woodworking experience, so I won’t be able to write a start from nowhere report that is as moving as yours. Congratulations on your success, and I hope you continue to relish the joy of new experiences that require some effort.

Toll gemacht, Mädel 🙂

As a German father of two girls, I had a painful grin in my face reading your report. Just imagine, what those terrible sharp tools can do to girls’ fingers …

Nevertheless, never ever a girl should be told to be unable for woodworking! So fathers of this world, keep at least your mouth shut if not able encouraging and giving compliments to your woodworking girl.

Your boat really looks very cute and well made. Do you know how heavy it is?

Nice story

I enjoyed your story and the joy you found in doing this project, which seems to have spread throughout the community from Ingrid, to neighbors, and beyond. Now how do I go about getting one of your chocolate cakes?

Good for you, Isabelle. Go girl! You proved to yourself and others in your life that you can do anything you put your mind to. Also, your kayak is as all good boats should be. Not just a boat but a work of art. It’s a thing of beauty.

Congratulations,

Wayne

Was für eine großartige Geschichte Ihres Projekts und Ihrer Reise zum Abschluss.

(what a great story of your project and journey to completion)

Really enjoyed your article! I know the feeling when others tell you “you can’t do that.” Don’t listen to them and plow ahead. With a little bit of thought, things can be built by yourself (with a few Kreg clamps), for example, a log cabin and a 18′ Glen-L boat named CHUG-A-LUG. Good looking boat you have there, Kiddo.

I always enjoy this magazine but I think this is the best tale so far. Thank you so much.

Wonderful story. I’m betting that this will only be the first of a line of home-built kayaks.

Beautiful boat.

Wonderful story.

Thank You!

Sehr gut gemacht Isabelle

Look up “courage” in the dictionary. It has your picture. Well done und sehr gut!(I think)

My complete respect to you on your project. Alleq is stunningly beautiful!

Congratulations, Isabelle, on constructing a beautiful kayak and an exceptionally entertaining and well-written story. Please write more!

A great and inspiring read and beautiful kayak, enjoyed all of it, the technical, the shops and lawns, and family. Thanks!

What an inspirational story! As for the level of support and encouragement one should get from a parent (especially a father when it comes to this kind of project), guys can also encounter discouragement from parents who don’t support their children in their endeavors. In my own case, my dad never told me to stay out of his shop or away from his tools. I started using his table saw as soon as I was tall enough to see over the table, and I still have all my fingers. I know people who never received that level of trust who are afraid to tackle anything, and are always seeking approval from others because they are afraid to take risks. I salute your for your intrepid determination. It would be wonderful to see a video of you rolling your new kayak

In my area (NW Washington state), I know several people who have built skin-on-frame kayaks, often with the guidance and coaching of Corey Freedman of Anacortes, WA. Though I myself have not built such a boat, I have made several wooden kayaks using kits from Pygmy Kayaks, of Port Townsend, WA (which unfortunately has ceased operation). As I am now incredibly old, and have a bum shoulder, I no longer have the confidence to roll my kayak, which means I try to stay upright.