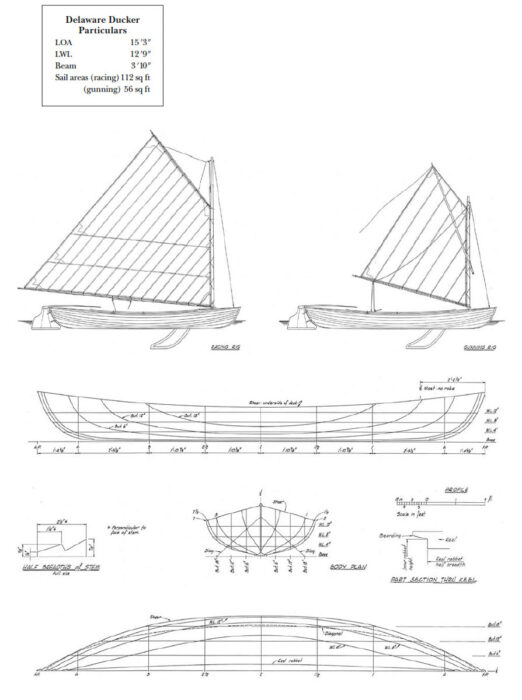

The Delaware ducker is a deceptively simple boat. It’s 15′ long, has a 4′ beam, and is low sided with side decks so that structurally there is no need for thwarts. There is a choice of rigs, depending on the crew’s intentions and abilities; they range from a 56-sq-ft gunning sail (as its name implies, the boat was developed for duck hunting) set with a sprit and a boom, to a 115-sq-ft gaff-headed racing rig.

The ducker is like a canoe: You need to step pretty close to the centerline when you board from the side. You need to have your hands on the coaming when you push off from the beach. And, if the wind is gusty, you must move from sitting or kneeling in the middle of the boat to the rail, where it seems you spend a goodly amount of time sitting on the low coaming. In short, it’s a sensitive boat that makes you move around.

Maynard Bray

Maynard BrayThe Delaware Ducker evolved as a bird-hunting boat on the tributaries of Delaware Bay. A study in simplicity and performance, it deserves close attention as a recreational boat.

If you have a passenger, the passenger can’t really row effectively unless you are working down a marsh and need someone to push-row looking ahead. Only if you are using the 65-sq-ft summer rig or the large racing rig can the passenger help balance the boat. So, the ducker is basically a singlehander, capable of carrying a passenger—a passenger who must move around to keep her moving. This is not a prescription for a highly marketable boat.

Still, the Ducker has some great virtues: It is one of the very few, perhaps the only, traditional working boat that would appeal to modern dinghy sailors—people used to boats that are tender and sensitive, boats that sail fast. There are no traditional boats that I know of that row as well as the ducker and can be sailed as well. It is one of the few traditional boats that will plane. It can be a demanding boat, but demanding boats are rewarding. There are boats that row faster and boats that sail faster, but there are few that will do both equally well.

I’ve owned my ducker, JOSEF W, for 30 years. She was built by Joe Liener in 1978 when he was an adviser to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, where I worked at the time. She is a copy of Joe’s own boat, GREENBRIAR. In honor of JOSEF W’s three decades, I had Nat Wilson replace her gunning sail last winter. He’d built the original sails, and the gunning sail had gone gray with age; patches were starting to go onto patches. With that new sail, I have been rediscovering the boat.

My first outing with the new sail on a local lake had fog and light wind. The 10-knot puffs coming through accelerated the boat to better than 4 knots, measured on the GPS. She’d ghost for a while as the puff died. When the breeze backed off, I needed to move from the side deck to the boat’s center in a hurry. Later, I took the boat out to my sister’s camp on a western Maine lake, rowing my wife the halfmile to the camp. A movable gunning box provides the rowing seat.

Ben Fuller

Ben FullerThe Ducker we see here is JOSEF W, author Ben Fuller’s 30-year-old copy of GREENBRIAR, whose plans reside at the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia.

Later, when the wind came up, I rowed back to pick up the rig and sailed for a while that day with a passenger who sat amidships on the bottom. The floorboards are a single structure—a “floor flat” that comes out in one piece and has cleats on it to position the gunning box. The box houses the oarlocks, compass, and other loose gear. The side decks are supported by metal rods that double as oar stowage. There is a removable V-shaped lunch platform that lives under the stern deck, and a removable stern seat for a passenger. My passenger and I used the gunning rig that day.

For singlehanding, the gunning rig is pretty versatile. It will move you in a drifter, when you think oars might be a better way to go. Its spars are short enough so they will stow in the boat or can easily be carried. I have sailed this rig in Force 6 winds and 4′ seas— conditions that push the ducker to its limits. With the low sides and the big open cockpit amidships, spray climbs aboard and from time to time you must bail. If your conditions are generally a short chop, this is not as much of a problem. A canvas rough-water deck would be easy to add. And in a breeze, when you turn onto a reach, you will see that planing this double-ender is quite possible.

The ducker will capsize or swamp. Water on the side decks gives you some warning, and turning loose sheet and tiller will let the boat ride neatly broadside to wind and sea. I have not capsized but have seen it done, jibing in a breeze. She will float crew and gear but not high enough to bail. For more demanding conditions I put canoe float bags under the stern and bow decks, and we have rigged at least one of the duckers with side flotation bags. These would give you a chance at bailing the boat.

When rowing without gear and rig, 4 knots is achievable in most conditions, and 3 knots is easy cruising. The Blackburn Challenge is an annual distance rowing race in Massachusetts, and I have done three of them in JOSEF W and finished with no more than 10-minute differences in varying weather. The boat even won the Blackburn in 1989. One must pull from the after rowlocks, as the boat trims bow-down when rowing from amidships, making the boat hard to handle. As an experiment I added a small rowing frame with a wheeled platform on which I can put the gunning box so that I can use a sliding-seat boat. While I don’t go significantly faster with this rig, I do get to use more muscles.

When you are sailing, the ducker demands your attention. But with the sail brailed up or just drifting under oars, that nice open cockpit is ideal for napping. She would easily carry singlehanded camping gear and a tent over cockpit, something that was done often on the Delaware in the original boats.

Ben Fuller Collection

Ben Fuller CollectionThe Ducker is ideal for double-handed daysailing or for singlehanded camping—which was one of the boat’s historical uses.

Sometimes, the sprit rig is the first element of this boat that captures people’s attention. The boom jaws are close to the deck, but the sail is cut with a high clew, so the tip of the boom easily clears the head of the sailor. There is also a furling line that runs from the head down around the boom, then back up and down the mast. One yank, and the sail, boom, and sprit are a bundle ready to be lifted out.

The hardware is elegant and functional. The rudder hardware is fitted to a curved rudder with a standard pintle-and-gudgeon arrangement at the bottom and two mating gudgeons at the top with a pin to connect them. There are small turning blocks on the foredeck to lead the snotter and furling line back to the cockpit for the larger sprit rig. The oarlocks sit on bronze pedestals that look like inverted cones, and the shank of the traditional oarlock is a little longer to fit them. Several padeyes are riveted into the boat’s bottom; they pass through holes in the floor flat. Traditionally, these eyes were used for hiking lines—short lines with T handles that support the hiker. I have rigged them with a toe strap, and added a hiking stick made from a bamboo ski pole to the tiller.

Joe Liener is no longer with us. He had retired to a spot near the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum from managing the Philadelphia Naval Yard’s small-boat shops, rising from a 3d class journeyman. His ducker, GREENBRIAR, is part of the CBMM collection, and the museum is making the ducker the centerpiece of their small-boat building program. If you don’t want to build one yourself, they would be happy to build one for you—as would the Apprenticeshop in Rockland, Maine, whose lead instructor, Kevin Carney, built mine. Another Apprenticeshop instructor, Brian McClellan, led the building of what may be the finest reproduction that has been built. You can do it yourself, too: using modern materials, the easy plank lines make glued-lap or strip-planking pretty painless. Glued-lap can be done in 5⁄16″ plywood, which is what Joe used to build GREENBRIAR.

Ben Fuller Collection

Ben Fuller CollectionDuckers were once ubiquitous. Given their recreational possibilities, it’s puzzling that we don’t see more of them.

It’s a little puzzling why we have not seen more duckers built in recent years. There have been perhaps half a dozen traditional ones built, mostly in museum and apprentice programs. Steve Clark, a highly experienced dinghy and sailing canoe sailor, saw the potential and built several cold-molded versions—and a mold for fiberglass hulls. People loved them at boat shows, but they did not buy. To my knowledge, one glued-lap version was built, taking the weight from around 150 lbs to 100 lbs; the cold-molded versions were as light as 60 lbs.

Were you to build, you’d have a choice of plans. Dave Dillion drew two splendid sets. Those for GREENBRIAR are in the collection of the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia. She has more deadrise and a flatter sheer than the other ducker that Dave drew— a boat given by John York to Mystic Seaport Museum. The York ducker is a bit steadier underfoot; this is the model used to build the cold-molded duckers.

JOSEF W may not be used as much as she once was. But I have worn out one set of oars and one sail, and there was a time that I commuted in her. Now she spends more time than she should hanging in the garage waiting to have a go. Perhaps she will if we can get more of these worthy craft built.

Dave Dillion

Dave DillionThe plans for GREENBRIAR, drawn by Dave Dillion and sold by the Independence Seaport Museum, specify two rig options: a small gunning sail and a larger racing sail.

Plans for the Delaware Ducker GREENBRIAR, and others, are available from the Independence Seaport Museum, Penn’s Landing, 211 South Columbus Blvd. & Walnut St., Philadelphia, PA 19106; 215–413–8638.

Thanks to Ben Fuller for letting me sail and row the Joseph F on my tour of the East Coast many years ago when I was racing my International Canoe. I bought plans and built the Elijah Harper in the 1990s and still use her for outings on the Salish Sea. She is one of my favorite boats and has seen a lot of use in the last 33 years. Ben’s comments on the boat ring true, a lovely design.