Before I took to small-boat cruising in 1980, I did a lot of backpacking and was acutely aware of the weight of everything I had to carry. The longer I planned to stay out on the trail, the more food I needed to pack and the lighter it had to be. Ready-made backpacking meals in the ’70s were expensive and not very interesting, which is putting it mildly for TVP (textured vegetable protein), then a popular camp staple.

Fortunately, I could instead carry real food, thanks to the dehydrator my mother used to preserve some of the fruit and vegetables we grew in our backyard garden. For backpacking, I dried a lot of fruit, especially bananas, and my mother’s black-bean soup, which instantly came back to life with a bit of hot water.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorBlack bean soup—made of canned black beans, boxed vegetable broth, diced onions, minced garlic, cumin, salt, and pepper—takes 15 minutes to make, 30 minutes to cook, and a few hours to dry. Puréed and spread on parchment paper, it dries feather-light and is just as tasty when reconstituted.

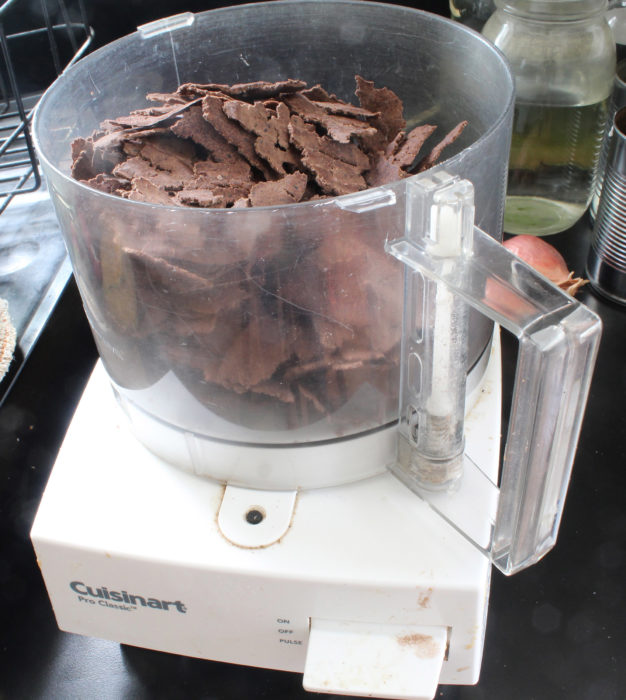

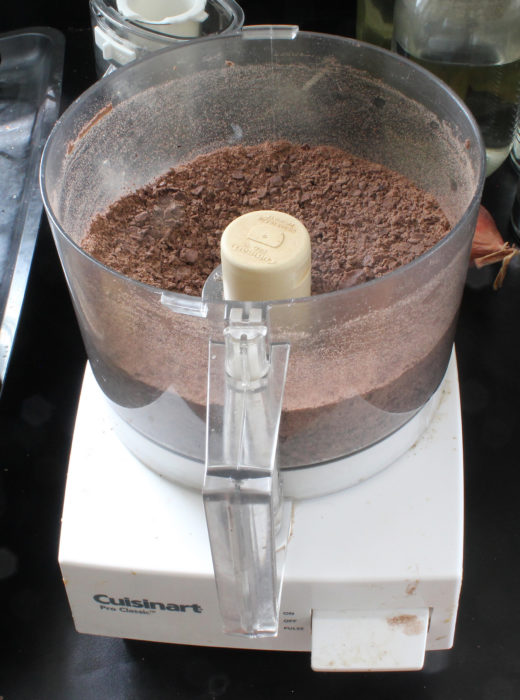

A food processor makes quick work of pulverizing dried soup.

The smaller the particles, the quicker they can rehydrate.

Basmati rice takes about 5 minutes to rehydrate and the black-bean soup reconstitutes almost instantly. I chopped some dried onion and added it to the mix without rehydrating. The rice-and-bean pairing adds protein to the diet.

For cruising, the boat takes the load off my back, so I’m not concerned about the weight of the food I carry aboard, but there are many soft foods such as tomatoes, bananas, and strawberries, that don’t travel well even when packed in rigid containers to protect them. Those containers take up a lot of space, even when they’re empty, while resealable plastic bags filled with dehydrated food require minimal space and take up progressively less room as the contents are consumed.

A 16-oz jar of salsa can be spread out on a single parchment-covered rack. Dried, it becomes leather-like and can be reconstituted with lukewarm water in about 10 minutes, faster with hot water. It’s a rather tasty snack, albeit a bit salty, when eaten dry.

To dry foods that are largely liquid—soups, salsa, and pasta sauce—spread them on a sheet of parchment baking paper placed on the dehydrator’s racks. Metal cans and glass jars can be left at home and the dried contents consumed over the course of several days without requiring refrigeration. For the sake of the environment, use compostable unbleached parchment paper. The paper can be used repeatedly, so one roll will last for a long time. It doesn’t transfer flavors from one drying to the next, so you don’t need to keep track of what each sheet was used for.

An entire 25.5-oz jar of pasta sauce takes two racks to dry and the leather it produces folds to fit easily in a small resealable bag.

A bit of water and about 5 minutes on the stove is all it takes to turn these dehydrated ingredients—diced onion, tomato slices, precooked elbow macaroni, and pasta-sauce leather—into dinner.

Parchment paper works for rice and quinoa, too. When those grains have been cooked and dehydrated at home, they require shorter cooking times and use less camp stove fuel when reconstituted during a cruise. To rehydrate rice, for example, bring 1 cup of water to a boil, add 2/3 cup dehydrated rice, turn the stove off, and let the pot sit, covered, for 10 to 15 minutes while the rice absorbs the water. You can turn the stove on for a short while before eating to heat the rice to your preference.

Cooked quinoa dehydrates well on parchment paper. Fully dried, it makes a very crunchy snack.

If you don’t have a food processor for breaking up dehydrated food, a rolling pin works well. Here it’s breaking clumps of basmati rice into individual grains.

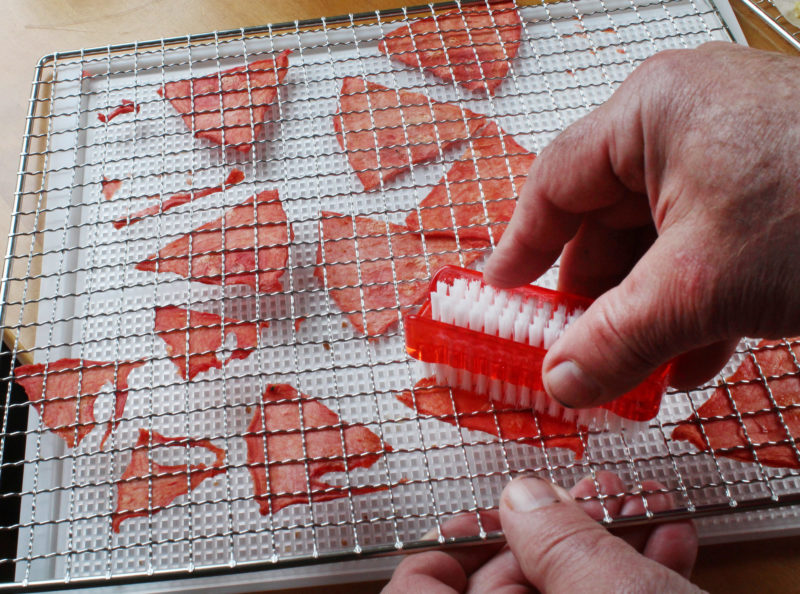

Some foods can be quite sticky and difficult to remove from the dehydrator’s trays. Watermelon, which becomes a delicious taffy-like candy when dehydrated, adheres to steel racks. A stiff-bristled fingernail brush (never used for fingernails) can push food off from the back side of the rack. Parchment paper can slow the drying a bit, but it makes it easier to remove sticky food.

If you find that some foods stick to the racks and are difficult to pry loose, a stiff-bristled brush can press them off from the back side of the rack. After this first try with 1/4″ slices of watermelon, I dried the next batch on parchment paper which made it easy to remove.

Dehydrators can also be used for meat—whether beef, chicken or fish—but in the form of jerky. I haven’t yet explored that possibility. There are many books devoted to dehydrating, with instructions and recipes for making different kinds of jerky and drying foods of all kinds.

A sampling of dehydrator projects, from left to right, top to bottom: pasta sauce, salsa, strawberries, onions, homemade black-bean soup, deli Bombay potato soup, Roma tomatoes, bananas, watermelon, croutons, lemons, apple.

There are many makes and models of food dehydrators on the market with prices starting as low as $35. The less expensive ones are made of plastic, with many using BPA-free materials for the food trays. I prefer a stainless-steel type for durability and to minimize my use of plastics. The Cosori 267 I bought has a digital control panel for setting the temperature from 95 to 165 degrees F, and the time up to 48 hours. It has an automatic shut-off to prevent the unit from overheating.

A bonus to dehydrating foods during the cooler months: the dehydrator produces heat, and rather than let that go to waste, I keep it in my study rather than in the kitchen. When I’m at work at my desk, the dehydrator can take the chill off the room, and I don’t need to use a space heater. The only sound is the rush of air moving through the unit, a pleasant whisper of white noise that is not at all distracting.

The 600-watt Cosori dehydrator has six stainless-steel racks and works quietly at 48dB, the range of average room noise. If my house is cold, I’ll move the dehydrator into the study to take the chill off while I work and make it easy to grab an occasional bite to eat.

Dehydrating food will add some time to your preparations for a cruise, but it’s well worth the effort. Some foods, like black-bean soup, are every bit as good when reconstituted and others, like watermelon, are transformed and intensified by dehydrating. And you can save food that might otherwise go to waste languishing in the kitchen.

The banana bread I make with dates and walnuts turns into biscotti when dehydrated. It needed chocolate (of course) and I found I could warm semi-sweet chocolate chips in the microwave for 90 seconds, then apply the melted chocolate with a spatula. A half hour in the refrigerator cools and dries it.

Drying food has a long history, and the possibilities are virtually endless. Turning banana bread into biscotti was a delightful discovery; I’ll do that often, whether I take the biscotti cruising or enjoy it at home.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

You can share your tips and tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Magazine readers by sending us an email.

Good article. Food for thought, as it were. I am wondering about how appealing some of these things, or others that can be thought of, would be with room temperature water, or perhaps water warmed by the sun under a dark cover would be. Sometimes the clutter of even a simple alcohol stove and can of fuel along with the effort to heat the meal seems not to be worth the effort after a long strenuous day.

What great ideas. But I was really hoping for the black bean soup recipe of your mother’s!

Here you go:

Black Bean Soup

1-1/2 Tbsp olive oil

3/4 cup diced onions

28 oz canned black beans with juices—don’t drain

2 tsp cumin

1/4 tsp salt

Pinch black pepper

3 cups vegetable broth

Bring a large pot to medium heat and add olive oil and onions. Reduce heat, stir, and cooked covered for 4 to 6 minutes until soft.

Add garlic and cook 1 to 2 minutes

Add black beans, cumin, salt, and pepper, and broth

Bring to boil. Reduce heat, simmer covered for 30 minutes

Blend until smooth with immersion blender or food processor

Dehydrating: Spread on parchment-paper on rack, dry until crispy, pulverize in food processor or with rolling pin.

Rehydrating: Put in a cup or bowl, about 1/2 to 2/3 the volume you’d like to eat. Add boiling water and stir until restored to consistency before dehydrating or thicker.

Great info, we are needing to build up a cruising-food menu. Our meals have to be gluten free so a lot of store-bought expedition meals don’t work for us. This gadget would allow us to just dehydrate some of our leftovers. And now we have a biscotti recipe as well 🙂

The banana bread recipe I use for the biscotti calls for gluten-free flour. I add about 3/4 cup chopped walnuts and 3/4 cup chopped Medjool dates.

Very thoughtful article. Thank you.

In reply to Steve Althaus: The trick for “rehydrator meals” on days where you know you’ll be too beat to even heat up water at sunset is Thermos Cooking (look it up). Basically, boil some extra water with your morning coffee, pour a bit into a Thermos to preheat, pour in your meal ingredients, top off with more boiling water and seal it up. Let it sit, eat later. Timing is key, some foods (rice) won’t do well sitting for 12 hours. Solution, two thermoses, one for hot water, one to “cook” in a few hours before final anchor-time. Three thermoses (thermosii?) if you want a hot lunch. Sounds like a lot of gear, but it’s not… You can get a few short, squat, bowl-sized thermosii for “cooking” (and as general dinnerware) and just one big tall one for your hot water. Cheers!In reply

Okay this was embarrassing: I sustained myself on rations of peanut butter, Cheeze Wiz, crackers, Cola, and instant ramen noodles. Looking back, I now know why I never felt that great after. Salt upon salt upon salt. I have a dehydrator…might as well use it!

I can highly recommend dehydrating cooked extra lean ground beef or ground chicken. These meats rehydrate with the full flavour you are looking for with a camp meal. Ground meats rehydrate quickly and are more appetizing in a recipe than is jerky. Curried chicken and rice, beef chile are two great cruising (or backpacking) meals.

A very brilliant article full of great information and the comments are just as great. With over four decades of mountaineering, sea kayaking, and small craft expeditions, I’ve always brought my own dehydrated food for I could mix and match to create a wider verity of meals. Thermos cooking is a great method of preparing meals ready to eat after a long challenging day. It greatly helps with personal and group moral, having a quick ready to eat warm/hot meal.

My husband is more a boater then I am. But I do love dehydrating, canning, all that stuff. Dehydrating is my favorite because it’s the easiest form of preserving foods. I’m also in several forums for storing foods.

But this article brought to point several simple things I’ve never heard of or if I did I’d forgotten. I (my husband) bought silicone drying sheets (they have a lip around the edges) for things such as dehydrating liquid Items such as fruits, eggs, etc. and I don’t ever recall anyone saying they used parchment paper! COOL!!! Love the dedicated fingernail brush idea. I’ll be getting one of those. And pointers about cooked rice/pasta/sauces and premodern soups! I’ll be looking into things such as Alfredo sauces etc. I think maybe because those of us who have food storages do canning, we don’t always think of dehydrating a lot of items for quick “cooking” but I will rethink my whole system. Many of these things dehydrated will take much less real-estate on my shelves in dehydrated form than in liquid form. Lots to think about and great for discussion in other forums. Awesome article!!