Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonThe Catspaw dinghy, Joel White’s adaptation of an 1899 Nathanael Greene Herreshoff design, is an excellent all-around daysailer that is stable, sails well, rows well, and tows well.

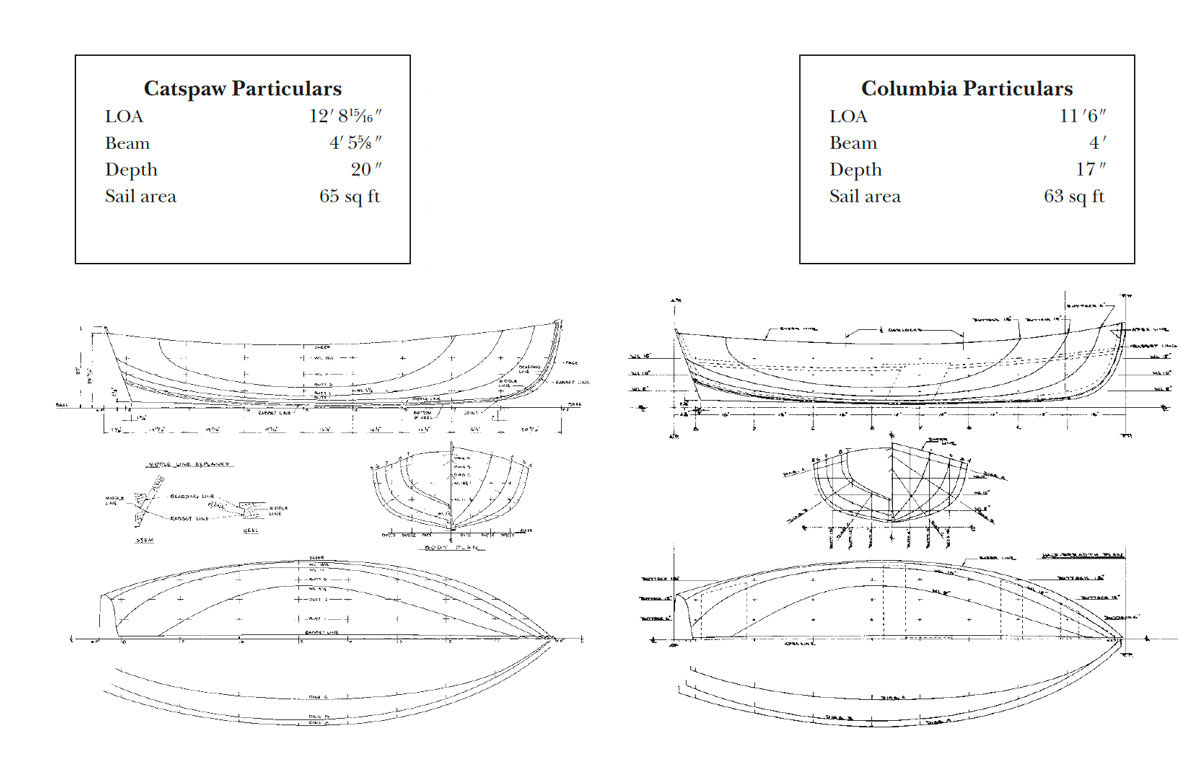

Good boats almost never fail to beget more good boats. Here’s a pairing of ancestor and offspring that proves the point as well as any could: the Columbia tender developed by Nathanael Greene Herreshoff in the last year of the 19th century and the Catspaw dinghy drawn by Joel White in the 1970s. The similarities are striking, but the differences are clear—nevertheless, either boat would be a fine choice for construction and use.

The tale must begin at the beginning. N.G. Herreshoff worked up a fine yacht tender—with lifeboat-style watertight chambers forward and aft—for COLUMBIA, which won the America’s Cup in 1899 and 1901. Amid the hoopla, somehow the lifeboat was so universally admired that it became a staple offering of the Herreshoff Mfg. Co. in Bristol, Rhode Island, for decades. A dizzying array of variations were built. Mystic Seaport in Connecticut has two of them in its watercraft collection, one a 1929 boat 12′ 6″ LOA with a 4′ 10″ beam with lifeboat-style chambers and the other an 11′ 6″ open boat from 1905. The latter was documented and replicated by Barry Thomas, then of the museum’s staff, in a noteworthy 1977 pamphlet, Building the Herreshoff Dinghy: The Manufacturers Method. For a grateful audience of small-boat craftsmen and for posterity, the book also recorded a surviving Herreshoff boatwright’s memories of the building technique and some specialized tools he used.

“This is the best model for a tender I have ever seen,” the designer’s equally famous son, L. Francis, wrote in 1948 in The Common Sense of Yacht Design. “They row well, sail well, and are good dry sea boats, and will tow through anything.” This was high praise, so it is small wonder that more than a century later the type still attracts considerable interest.

Thank goodness that not all yacht owners these days insist on dragging an embarrassing battleship-gray inflatable astern in order, it seems, to avoid rowing at all costs or under any circumstances. In 2008, a group of like-minded yachtsmen gave us an extraordinary example of excellent taste in tenders. For simultaneous restorations of four Herreshoff Buzzards Bay 30s—three of them side-by-side at the French & Webb shop in Belfast, Maine, and one in Darling’s Boatworks in Vermont (see WoodenBoat No. 203)—three of the owners carried their vision through to a fine conclusion by ordering Columbia dinghies as tenders. Named for their waterline lengths, the Buzzards Bay 30s are magnificent yachts, magnificently restored, and their tenders superbly complement the yachts themselves.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonBuilt by Taylor & Snediker Woodworking of Pawcatuck, Connecticut, the bright-finished Columbia tender for the Buzzards Bay 30 YOUNG MISS is a lovely construction, light yet strong.

Two of these tenders were for oars only and were fitted with lifeboat chambers fore and aft. The other was an open boat, set up for sailing. At 11′ 6″ LOA and 3′ 11″ beam, they are slightly smaller than the 14′ original lifeboat. All three were built the Herreshoff way by Taylor & Snediker Woodworking in Pawcatuck, Connecticut. (David Taylor, who worked with Ed McClave of MP&G in Connecticut on the research for the three dinghies, presented a paper on the boats to the 2009 Classic Yacht Symposium at the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol, Rhode Island. More Columbia dinghies came later: a full-sized version was constructed to exacting standards at Stonington Boat Works in 2009 for the restored Herreshoff New York 50 sloop SPARTAN, restored by MP&G in Mystic, Connecticut, and Taylor & Snediker built a 15′ 6″ version for a 163′ ketch built in New Zealand.)

When I took YOUNG MISS’s tender for a row around Belfast Harbor, the first thing that struck me was the boat’s delicate construction. Her steam-bent white oak frames are only 1⁄2″ × 1⁄2″, and her Atlantic white cedar planking a mere 1⁄4″ thick. With her mahogany sheerstrakes molded in the Herreshoff manner (see WoodenBoat No. 208) and mahogany trim, she is fine-looking under any circumstance, but never more so than when alongside the mother yacht herself. True to Herreshoff’s original, this one has watertight chambers fore and aft. The after bulkhead doubles as a seat back for the passenger’s thwart and in time-honored fashion carries the name of the yacht in gold-leaf lettering. Bronze lifting rings are fitted on the centerline near the stem and the transom. With these fine details and her all-varnished interior and topsides, the tender is a very handsome boat in her own right, regardless of what yacht she may be nestled against.

Beyond her appearance, however, is her performance. She is a delight to row. The boat has quite high freeboard, but with oars of the proper length—these were 7 1⁄2-footers—she moves very comfortably. She is also incredibly stable. I walked around in the boat with no worries about balance. Soon I noticed that the boat doesn’t seem to appreciate aggressive rowing, but you can readily settle in to an all-day pace. She will move so steadily at this rate that you begin to feel that you’re merely along for the ride, accompanied by the cheerful chortling of water against her plank laps. I can’t recall a more comfortable rowing setup than this one in a boat of this type, nor a greater feeling of security. I’ve no doubt the boat would sail in comfort as well.

A boatbuilder with experience could readily build such a boat. Rather than plowing through the historical records to try to reconstruct original lines—a daunting task even for professionals—the builder would be well-advised to work from existing plans. R.A. Pettaway’s detailed lines, table of offsets, Bermudan-rig sail plan, and construction plan for Mystic Seaport’s 11′ 6″ boat were included in Barry Thomas’s pamphlet, which is still readily available. This boat, I should note, did not have the lifeboatstyle chambers, so building-in such flotation would require additional planning and judgment on the part of the builder desiring them.

A serious builder could replicate Herreshoff’s methods if so inclined—which for this boat most notably called for a building mold at every second frame position, or 10 molds altogether. Frames were steam-bent directly to these molds, the rest installed after planking. An experienced builder could also devise a typical building jig—with ribbands sprung over fewer molds. There’s also no reason why the hull couldn’t be planked in glued-lapstrake plywood.

The story of the Columbia lifeboat would have been a fine one—a classic—even if it ended there. But it didn’t. The story took a new turn with Joel White.

White, often inspired by Herreshoff boats, worked here in Brooklin, on the granite-bound coast of Maine. Among his successes was the famous Haven 12 1⁄2, a centerboard version of the Herreshoff 12 1⁄2. When a client came to White looking for something like a Columbia dinghy, White thought to preserve the design’s essence while applying the logic imposed by this environment. Here, the boat would not spend a good deal of its life hoisted aboard a yacht or at a yacht club dinghy dock. Instead, it would ground out routinely on stony beaches and might often be dragged up above the tide line. Varnished topsides would be a mistake. Thin planking could easily be damaged. The original boat’s great all-around performance could be retained, but the hull would need to be more resilient.

White named his resulting design the Catspaw dinghy, completing the work in 1977. The boat, which was the subject of the first thoroughgoing, multi-part “how to build” series in WoodenBoat magazine (WoodenBoat Nos. 26, 27, and 28), became widely popular. For years, the design has been, and continues to be, one of the staple boats of WoodenBoat School’s Fundamentals of Boatbuilding course. Hundreds of plans have been sold, and who knows how many have been built.

What’s different? For starters, the Catspaw is a carvel, or smooth-skin, construction. Instead of riveted, overlapping planks, these are riveted to the frames only, and where the plank edges butt against one another, the seams are caulked in the traditional way with cotton. The planking has to be 1⁄2″, instead of 1⁄4″, for this type of construction, so the boat is heavier. White also made it 10 percent longer—12′ 9″ instead of 11′ 6″—to better accommodate family daysailing. Reasoning that the original’s daggerboard could damage the hull if it smacked hard into a submerged rock, White used a centerboard instead, which would pivot upward and spare the hull itself any harm. He drew a simple sprit rig, which has no boom and poses no risk of knocking heads when tacking. Like Mystic Seaport’s original 1905 version, White’s boat omitted the lifeboat-style chambers but retained the simple interior arrangement.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonBeing able to run up on a beach in Maine—definitely a desirable trait—calls for the stouter 1⁄2″ planking used on the Catspaw dinghy. For hoisting Columbia dinghies aboard a yacht, the light weight of the original light lapstrake construction was preferred.

These days, some people may be tempted to look at something other than carvel construction for the Catspaw. It could be built handsomely in lapstrake construction. Strip-building would work. But I suspect that many intending to launch from a trailer for each outing will look to cold-molding, using glued-up overlapping layers of wood veneer. Carvel-built boats have to be given some days to “take up” after launching, and until they do, they will leak, sometimes considerably. For those without access to a mooring, marina, or dinghy dock, cold-molding would be a reasonable choice. Builders choosing this method will have to make adjustments to the mold patterns for their setup, and those unfamiliar with the technique would need to do considerable study, or perhaps take a course. Builders I respect also caution assertively against making such a hull too light.

For all of the 12 years that I’ve worked at WoodenBoat, the Catspaw dinghy JESSE—carvel-built at The WoodenBoat School in the mid-1980s—has been quietly riding to her mooring off our waterfront. To renew our acquaintance, I took her out in a pleasant 10 to 12 knots of breeze. The rigging is as simple as it gets. With no stay or shrouds, the mast stepped quickly while the boat was alongside the float. The sprit slips into a loop at the peak of the sail and its heel fits into a kind of sling called a snotter, which hauls taut and is made off to a cleat on the mast. The only other line is the single sheet, which takes a turn around a thumb cleat well aft on the rail. To tack or jibe, you just free the sheet from this cleat and take a turn on the corresponding cleat on the opposite side. The plans call for two such cleats per side for more control over the sheeting angle depending on the point of sail—a good idea.

I rowed JESSE a few days later, choosing a breezy day with gusts to perhaps 16 knots. The characteristic I noted on YOUNG MISS’s Columbia dinghy I saw again—she doesn’t like to be pushed too hard. The all-day pace works best. I easily made steady headway into wind and tide, and seas of a couple of feet posed no problem at all. The boat felt a little heavier than YOUNG MISS’s tender, but not enough to be a bother. One quibble I had with both boats is that they really should have foot braces for rowing; neither had them, and both would benefit.

Joel White and R.A. Pettaway/Mystic Seaport

Joel White and R.A. Pettaway/Mystic SeaportThough their construction methods are completely different, the larger Catspaw dinghy, left, and its predecessor, the Columbia dinghy, right, have very similar hull shapes.

Both in sailing and in rowing, JESSE seemed extremely secure, with ample freeboard and loads of stability. When I was putting the rig away, I did something I like to do with sprit-rigged sails. I freed the sprit heel from the snotter, swayed it aft, folded the leech of the sail around it, rolled the sail up tight in the sprit until it was up against the mast, then tied it all off with the sheet to hold it there, making a self-contained bundle. From YOUNG MISS’s tender I knew something about this hull’s stability, but I was a bit astonished at how steady the Catspaw remained even while I was way up forward in the “eyes” of the boat, manhandling the bundle out of the mast step and partner for stowage. That sense of security is a high recommendation for a boat and inspires confidence in her ability to handle just about anything that comes her way.

She does everything well, but nothing to a fare-theewell. She rows steadily, but she is not a racing shell. She sails efficiently, but she is no close-winded sloop. She’s no cartopper, but she’s not unduly heavy, either, and would trailer handily. Her freeboard is ample but not so much as to make her look clumsy, which she distinctly does not. She could carry a load of people or gear or both. She is, in short, a worthy successor to the Columbia’s character as an “all-around” good boat.

All in all, it’s a story with a happy ending—but for the builder of either of these fine dinghies, the story would be just beginning.

Detailed plans for the 12′ Catspaw dinghy are available from The WoodenBoat Store. Be sure to check out our in-depth look of the Catspaw Dinghy design for more details.

Plans for the 11′ 6″ Columbia dinghy have been published in Barry Thomas’s book, Building the Herreshoff Dinghy: The Manufacturers Method (Mystic Seaport Museum, Connecticut, 1977). That book and two others mentioned in this article—How to Build the Catspaw Dinghy: A Boat for Oar and Sail, WoodenBoat Editors (WoodenBoat Publications, Brooklin, Maine, 1980); and Mystic Seaport Museum Watercraft, Maynard Bray, Ben Fuller, and Peter Vermilya (Mystic Seaport Museum, Connecticut, 2008)—are all available from The WoodenBoat Store.

Contact Taylor & Snediker Woodworking at 22 Mechanic St., Pawcatuck, CT

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.