After years spent exploring Baja California’s Bahía Magdalena in MADRINA, my 19′ 6″ Iain Oughtred Sooty Tern—an ideal boat for the job—I was beginning to feel my advancing age. It wasn’t only the sore muscles and creaking joints as I settled onto the floorboards, squeezed in next to the centerboard trunk for another long night of intermittent sleep; nor the dampness inside my cockpit tent, nor another meal cooked on a stove set on those same floorboards between my upraised knees. No, the larger question that returned whenever I thought about replacing MADRINA with something a wee bit more comfortable, and thus more substantial, was simply: If I’m ever going to tackle a bigger boat project, hadn’t I better begin now rather than later?

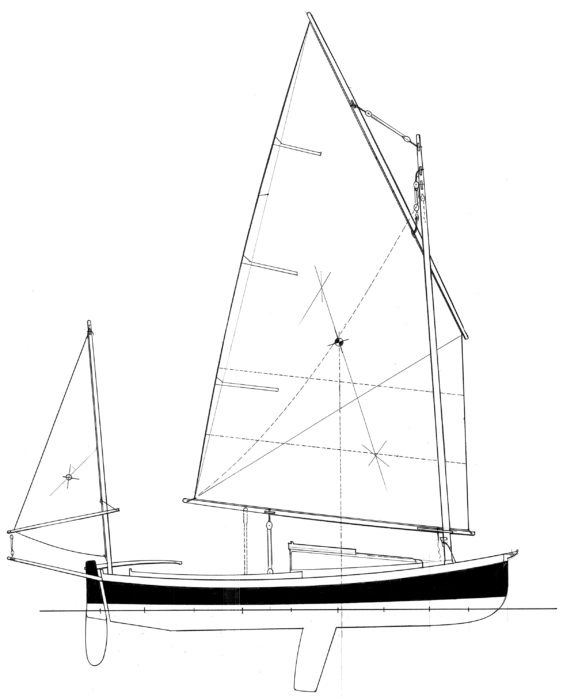

From the moment I opened my copy of Plans & Dreams Vol. 1, Paul Gartside’s first collection of plans and invaluable essays originally published in Water Craft magazine, I was taken by the 19′ 9 3⁄4″ centerboard lugger, his Design #166. I was particularly drawn to the simple standing lug, a rig with which I was already familiar, and imagined the design approaching that sweet spot between size, seaworthiness, and ease of handling. Also, having already built Gartside’s Design #130, a 12′ dinghy, I remembered the wealth of detail included in his plans, the breadth of classic, old-school building techniques they revealed, and that Gartside himself had been always quick to respond to questions.

Scott Sadil

Scott SadilOut of the water the sweet lines of Gartside’s design are clearly visible: the fine entry and aft skeg enhance performance both under sail and when rowed; the gently curved sheerline complements the sloping cabintop. For trailering, the boom crutch—used to support the main boom when at anchor—is moved aft to stand in the mizzen maststep to support the head of the mast.

Still, for months I hemmed and hawed. No question, Design #166 was a lot of boat: decks, cabin, exterior ballast, a tricky forward maststep, an impressive freestanding mainmast. Did I really want to commit to the time and expense of a job this size? Eventually, I realized there was only one answer: If not now, when?

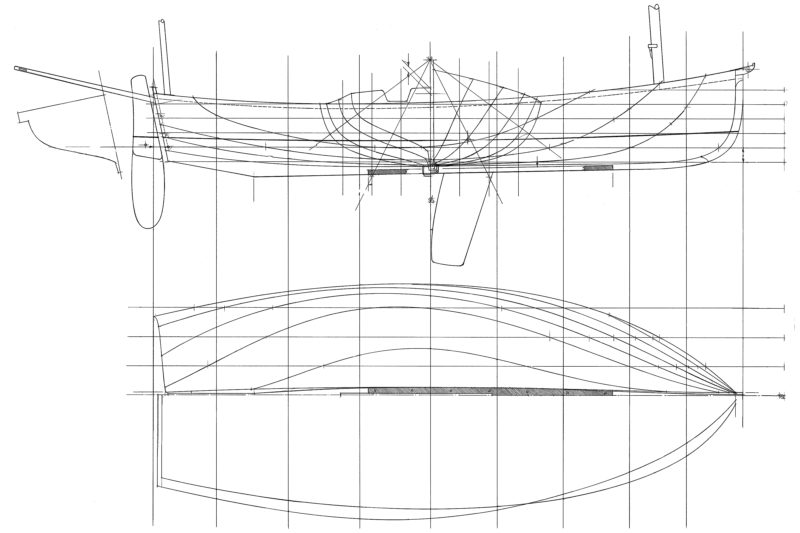

Although the plans for #166 show two construction choices—strip-planked and ’glass, or glued-clinker plywood—Gartside states, in his essay that accompanies the plans, that his own first choice for the hull would be “cold molding: a triple-skin layup of two diagonal and one fore and aft to finish about 12mm thick would be perfect and require little in the way of framing.” I was sold. I contacted Gartside and he drew up another page of construction details for cold-molding, bringing my set of plans to eight pages in all: lines plan, table of offsets, construction details, stem and maststep details, layout, sail plan, and the original setup detail for strip-plank or glued-plywood construction. There were no patterns. Throughout his writing Gartside advocates strongly for lofting: “Avoid the temptation,” he argues, “to shortcut the process.”

I did my lofting on plywood sheets spread out across my living-room floor, built my molds, and ordered up a load of western red cedar “shingle stock”—wide, uneven material (minimum thickness 4mm)—that I ran through a thickness planer to 4mm and then ripped into 4″-wide planking stock—narrow enough to fit the shape of the hull but not so narrow that I ended up with an unmanageable number of pieces. Gartside leaves the plank width to the builder’s discretion. The plans detail eight molds, and 13 battens measuring 3⁄4″ × 1 1⁄4″.

I applied the two opposing diagonal layers of planks and the final fore-and-aft layer and, after fairing the hull one last time, I sheathed it with a layer of 6-oz fiberglass saturated with epoxy. I used a two-part epoxy paint for the hull—further protection for the cedar hull. When a group of friends helped me to lift the hull from the molds, carry it outside and turn it over, I was surprised by its light weight even though the #166 hull is 1′ 7 3⁄4″ longer and 2′ 1 3⁄4″ wider than the Sooty Tern. Then, I was struck by the boat’s dimensions: mid-flip, when standing on its side, the hull stood far taller than my helpers—I was dealing with a boat of much greater size.

Kim Boehler

Kim BoehlerThe pivoting rudder blade doesn’t rely on weight to submerge it from its retracted position it. Its haul-up and haul-down lines are secured by a jam cleat on the tiller. The motor mount, mizzen mast, and boomkin are all offset so a standard tiller can occupy the centerline.

The lugger was also more complex. Among other testing elements in the build, it has a keel with 305 lbs of recessed external lead ballast—a great comfort when the 191-sq-ft mainsail fills with wind, but a construction challenge to be approached with care and consideration. The forward mast tube is also challenging. It is an aluminum sleeve that houses the maststep and runs from the deck, down through the forward flotation chamber, and drains downward through the keel itself. Its construction and installation involve some low-tolerance engineering that demands competency with this sort of metalwork. The plan details are explicit: the tube is fashioned in three parts that must be welded together and the heel plug, also clearly shown, is best machined out of high-density plastic.

The final challenges were in finding all of the hardware for the finished boat. I wanted to stick with silicon-bronze fittings as an appropriate match for a boat with such handsome, traditional lines, but could find nothing suitable at any chandlery. In the end I went with bronze fittings cast at Port Townsend Foundry, Tufnol blocks, and three-strand lines.

The free-standing mast is 22′ long and a full 4 1⁄4″ in diameter at deck level. I built it out of a single piece of Douglas fir, 10″ x 2 1⁄3″ × 26′, ripped down the center, ends swapped, the two halves hollowed out—as per the plans—starting 1,200mm up from the bottom and ending 600mm from the top. I kept the wall thickness to no less than the specified 25% of the outside diameter and epoxied the two halves together to complete the blank.

From start to finish, building TAMALITA took just under three years. Of course, the challenges would fade quickly from memory if I ended up with a boat that lived up to my expectations.

My goal was to replicate the shoal-water attributes of my Sooty Tern: easy singlehandling, good speed under sail, maneuverability under oars. I also hoped to enjoy the added comfort of a small cuddy as well as the security of side decks, coaming, and external ballast when I ventured out onto California’s open Pacific Coast.

The cockpit is expansive. In the text that accompanies the plans, Gartside calls his lugger “a daysailer first and foremost.” Indeed, for an outing with friends it would be ideal—you could distribute six adults along the two side benches. The cuddy is small but still usable: large enough for a single wide berth, lots of floor space, a tiny galley, and what Gartside refers to as “the illusion of privacy for the head.”

This shallow-draft, flat-floored boat will also please sailors who have trailered any boat near this size in the past. It’s easy to launch and retrieve at any typical launch ramp. It’s also light for a boat of its length. My trailer is a standard model although the axle position was adjusted to suit a sailboat rather than a sportfisherman with a heavy motor hanging from the stern.

Kathleen Wilder

Kathleen WilderFor its size the lugger has a generous sail area. Most of the power comes from the 191 sq ft balance lug mainsail but the off-center leg o’ mutton mizzen sail can provide a bit of a boost and be tuned to achieve a neutral helm.

Setting up before launching offers some challenges. Anticipating what it takes to step the free-standing mast, Gartside added a second step 15″ aft of the main step. “The mizzen,” he writes, “is dropped in here first and used as a crane to lift the mainmast.” It takes some time to tweak and adjust the rigging, and the first time you raise the mainmast overhead, expect to feel your heart flutter. As a newcomer to the boat, I got some extra practice stepping and unstepping the mainmast while working through the mainsail rigging. Four lines lead back to the cockpit—throat halyard, peak halyard, parrel line for snugging the yard to the mast, and topping lift—the easy-to-handle setup is perfect for the singlehander once everything is sorted and in place. Once the lines are all rigged, they can be left in place. After gaining experience, I can step the masts, hang the rudder, go through my checklists, fuss with this and that, launch, and be sailing easily within an hour.

For a relative novice like myself, the boat is a delight to sail. With the substantial ballast built into the keel, its shapely hull carries the big mainsail well. The off-center mizzen will also make a lot of sailors happy, as it allows for the swing of a conventional tiller rather than the push-pull steerage seen on many small boats with two-masted rigs. I have sailed luggers most of my brief sailing career and find that Gartside’s points at least as high as I’m used to. Its peak halyard helps to keep the mainsail from twisting. The boat comes about easily, and if you do need a little extra turning momentum in light air, you can snug the mizzen in tight and hold the boom for a moment to backwind the mainsail. Adjusting the mizzen also takes care of any weather helm.

With the side decks and cockpit coaming, even in a stiff blow if the hull does dip a rail, the water stays out of the cockpit. Given a tough chance, however, there are three large watertight flotation compartments, one forward, and one on either side beneath the side decks aft of the cabin bulkhead. According to Gartside, the lugger will float upright if swamped.

Kim Boehler

Kim BoehlerThe author prefers to row standing up and facing forward—a position that offers excellent visibility ahead. Although the mainmast was not stepped in this picture, even when it is in place, the boom and yard can be raised above the rower’s head with the topping lift.

The boat moves smartly under 9′ oars, which are the longest that can be stored on deck. I row from a standing position in the cockpit so wouldn’t want to have to fight much of a wind, but if there’s a breeze, I could sail instead of row.

Finally, although I was initially reluctant to have a small outboard dangling from the transom, Gartside had included the arrangement in his plans, and I went with it. The first time I found myself in Baja’s Magdalena Bay in the face of a stiff wind and a foul tide, I felt lucky to have followed the designer’s lead. Aside from that episode, I’ve never felt the need to use my 5-hp Mercury propane motor for more than a few minutes at a time.

Scott Sadil

Scott SadilFor singlehanded cruising the lugger has much to offer: its flat ’midships sections allow it to sit upright when beached; the small cabin proves comfortable shelter for overnights; and the uncluttered spacious cockpit with angled coamings is a relaxing place in which to sail or just sit and enjoy the view.

With the retractable rudder blade, the lugger can be beached and will sit level and upright on a flat bottom. I prefer not to beach if there is any surf and on extended voyages I tow an inflatable stand-up paddleboard, which I use as a tender.

Headroom is limited, and at anchor I spend much of my domestic time seated atop the cabinet between the galley and the centerboard trunk, my head poking through the companionway. With the hatch closed, however, and vented washboards in place, the cabin is dry, quiet, and cozy. A small fan forward adds to the luxury as I stretch out on the spacious berth.

Paul Gartside’s Design #166 has many of the attributes and even comforts not often associated with small boats. He calls it a small boat and “a very simple boat.” Both descriptions have much to do with point of view. Gartside is surely a master of boat design and building. For mere commonfolk like myself, his Design #166 is neither small nor simple; rather, it is a big boat for big adventure, and an elegant piece of his legacy.![]()

Scott Sadil decided he needed to learn how to sail while he was building his first boat, TÍA, a Chesapeake Light Craft Northeaster Dory, a dozen years ago. He is currently the angling editor at Gray’s Sporting Journal and the author of six books, both fiction and nonfiction, that weave essays and stories into the sport of fly-fishing.

Centerboard Lugger Design #166 Particulars

[table]

LOD/19′ 10″

LWL/18′ 11″

Beam/7′ 6″

Draft/1′–4′

Displacement/1,405 lbs

Ballast/304 lbs

Sail area/214 sq ft

Mizzen/23 sq ft

Main/191 sq ft

[/table]

Plans for Paul Gartside’s Design #166 are available from gartsideboats.com, $360. Study plans are also available: $20 for electronic delivery, $40 for printed.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us!

What a beautiful little vessel. I love the plumb bow look, the fine entry and sweeping sheer line. Great choice of colours. Paul is doing a small stich-and-glue catboat for me now. Can’t wait to receive the plans.

This boat has been on my long list of designs to build for a while. I have trawled the internet trying to find examples that have been built with very little success. It is great to see a full write up of this build. It looks wonderful. Congratulations to the designer and the builder.

David

I am a newbie and need coaching. Is this a standing lug or a balanced lug rig?

That’s a balance lug rig. It has a boom that extends the forward lower corner of the sail—the tack—forward of the mast. A standing lug rig, with or without a boom, has the tack set at the mast.

—Ed.

Wonderful build story and review of the boat. It does indeed look sweet and appears to have that nice mix of stability and slipperiness. In many ways it kind of reminds me of Phil Bolger’s Chebacco. With very similar dimensions and a slightly different rig. Had you considered it as well ?

The Bolger design, as much as I, personally, love it, is subject to a significant flaw, in that it is unrecoverable from a capsize without major assistance. This was displayed during a test at the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival, some years ago, and is, I believe, documented in a YouTube video.

I have slightly bigger Gartside boat, 21’ – no cuddy, but I have a tent, mainly to keep rainwater out but there is enough space for sleeping. Boat is gaff rigged with headsail and topsail, it sails sprightly and can take some wind without reefing – I try to avoid weather that reduces the fun of sailing…

I have made some videos at youtube channel “Seppo E,” some daysails and one overnight, and some work that I‘ve done during winter.

Beautiful! Someone ought to produce them in fiberglass.

Love your article, and the boat is truly beautiful. I built Paul Gartside’s Loopen a couple of years ago, using the cold molded method. You are too modest. It was the most difficult and time-consuming project I had done to date, and I had built five boats prior.

Dave Johnson

Nice! How easy is it to work at the mast (i.e., in raising, lowering and adjusting that big lug sail), given the cabin trunk blocking access?

Is Paul Gartside is still in favour of traditional lofting? For 30 years computer software has been available enabling hull drawings to be faired to such an extent that NO fairing of the shadow moulds is needed (provided the set-up is accurate), and millimetre-perfect drawings of apron, transom, and any bulkheads/floors (fore and aft faces) can easily be generated and printed full size. Such software has the benefit of enabling good design of buoyancy tanks, and of course checking static hydrostatics and righting curves. This article, “Strange and CAD, may be of interest to readers.

This deserves to be built often and to be seen sailing the worlds many lakes and rivers.