Here we have a distinctive, easily built, shoal-draft cruising yawl. The 25’3″ Black Skimmer floats in 10″ of water and sails handily in not much more. She stays with, or ahead of, most stock boats of comparable size on all points (including to windward)…and nearly always outdistances cruisers of similar cost.

Skimmer finds her heritage in the working sharpies of the Atlantic coast. In plain terms, these ancestors can be described as relatively narrow, flat-bottomed skiffs that have grown in length. Properly designed sharpies offer impressive performance in return for modest investments of time and money.

Black Skimmer comes from a happy coincidence of natural design evolution and contemporary materials (plywood and epoxy). The early 1970s found me in need of a shallow cruiser for exploring the hidden creeks that disappear into the shores of lower Chesapeake Bay. The available stock boats seemed too deep, too complex, and too expensive. To my good fortune, the late Philip C. Bolger was writing for Small Boat Journal at the time.

In each issue of SBJ, the Gloucester, Massachusetts, designer presented a “cartoon”…a preliminary boat design created to meet the specific requests of an individual reader. The images often were striking, and the aesthetics sometimes…well, surprising. But the proposed designs always seemed perfectly suited to the clients’ needs. The designer’s essays, which accompanied the cartoons, were filled with sharp wit and clear insight. It occurred to me that working with Mr. Bolger to devise a new boat might prove good fun.

Photo by Mike O'Brian

Photo by Mike O'BrianBlack Skimmer awaits her first taste of the Chesapeake Bay’s tidewaters, the marshy and shoal-water environment for which she was designed. The year was 1973, the beginning of a long association between boatbuilder and author Mike O’Brien and designer Philip C. Bolger.

After some thought, I sent him a list of requirements for a sailing cruiser. The new boat should be easily, quickly, and inexpensively built; cruise a crew of two in relative comfort; float in less than a foot of water and sail, really sail, in less than two feet; be self-righting, self-bailing, and have positive flotation; and be able to take the ground absolutely upright without sustaining damage.

After only 10 days of anxious waiting, I found Bol- ger’s first cartoon in our mailbox. A rough sketch, penciled on a sheet of common typing paper, showed a 25′ leeboard sharpie with twin inboard rudders. The proposal looked fine, but the rudders with their purpose-made hardware seemed to conflict with the theme of minimum cost, and the blades likely would snag crab-pot warp all the way to the Eastern Shore and back. We agreed to replace them with a single kick-up rudder mounted outboard on the transom. After due thought, the designer found something in his cartoon that bothered him: the bow was “too prominent.” He lowered it.

The final drawings, which arrived just three weeks after the preliminary sketch, offered a few surprises. Bolger had moved the mizzenmast back hard against the transom and had set it off to one side in order to clear the rudder. The asymmetry seemed to make fine sense, but I worried that the farther-aft location of the sail plan’s geometric center would result in too much weather helm. Bolger explained the change: it seems that some boats of this type had been having lee-helm problems, and he’d warrant that Black Skimmer would have none. Indeed, as things turned out after the boat was built, the yawl balanced perfectly under sail (slight weather helm) with the leeboards hung precisely where the designer had drawn them.

Photo by Mike O'Brien

Photo by Mike O'BrienLeeboards, which give the design its lateral resistance, can be raised and lowered as needed based on conditions, point of sail, and water depth.The boat sails well in less than 2’ of water.

Yet another surprise appeared in the final tracings: a previously unmentioned bow-well appeared forward of the first bulkhead. Keeping any concerns about flooding to myself, I built the well as drawn. In a decade of sailing up and down Chesapeake Bay, that open well never took green water. It did, however, regularly carry dirty ground tackle, the bagged mainsail, and crew members who desired solitude.

Although Skimmer might appear radical to some eyes, she is composed of design elements that have been well tested through the years. Successful flat-bottomed sharpies nearly always show adequate rocker (longitudinal curvature) to their bottoms; and the heels of their stems are carried at, or clear of, the water’s surface. This configuration reduces crossflow at the chines, resulting in better performance in light air. When the breeze comes on, the steering remains docile and predictable. Flat-bottomed boats with insufficient rocker often seem prone to rooting, broaching, and other unpleasant behavior.

For lateral resistance, Skimmer depends upon leeboards, a large rudder, and hard chines with external logs. The leeboards contribute to Skimmer’s performance in ways that centerboards cannot match. Each leeboard needs to work on only one tack, so it can be shaped and positioned for maximum performance. The working board angles away from the hull and presents an efficient, nearly perpendicular face to the water as the boat heels to her sailing lines. A small amount of toe-in relative to the boat’s centerline can increase lift (some designers specify asymmetrical foils for the same reason), but Bolger cautioned against overdoing it. Leeboards don’t intrude on the accommodations, and they remain effective in extremely shallow water long after centerboards have retreated entirely within their trunks.

An idle leeboard, perched on the weather rail, provides 120 lbs of effective and uncomplaining all-weather ballast. Some sailors dislike the appearance of leeboards, but to me they have the look of folded wings when the boat is at rest—and I’m happy to be done with centerboard trunk maintenance.

Photo by Mike O'Brien

Photo by Mike O'BrienA sprit-boomed “leg-o’-mutton” rig makes sail handling easy. Note that the mizzen is offset to starboard to clear the centerline for tiller steering for the transom-mounted rudder. The bow-high attitude of the dinghy astern (a Bolger-designed Gloucester Light Dory) gives a sense of Black Skimmer’s speed.

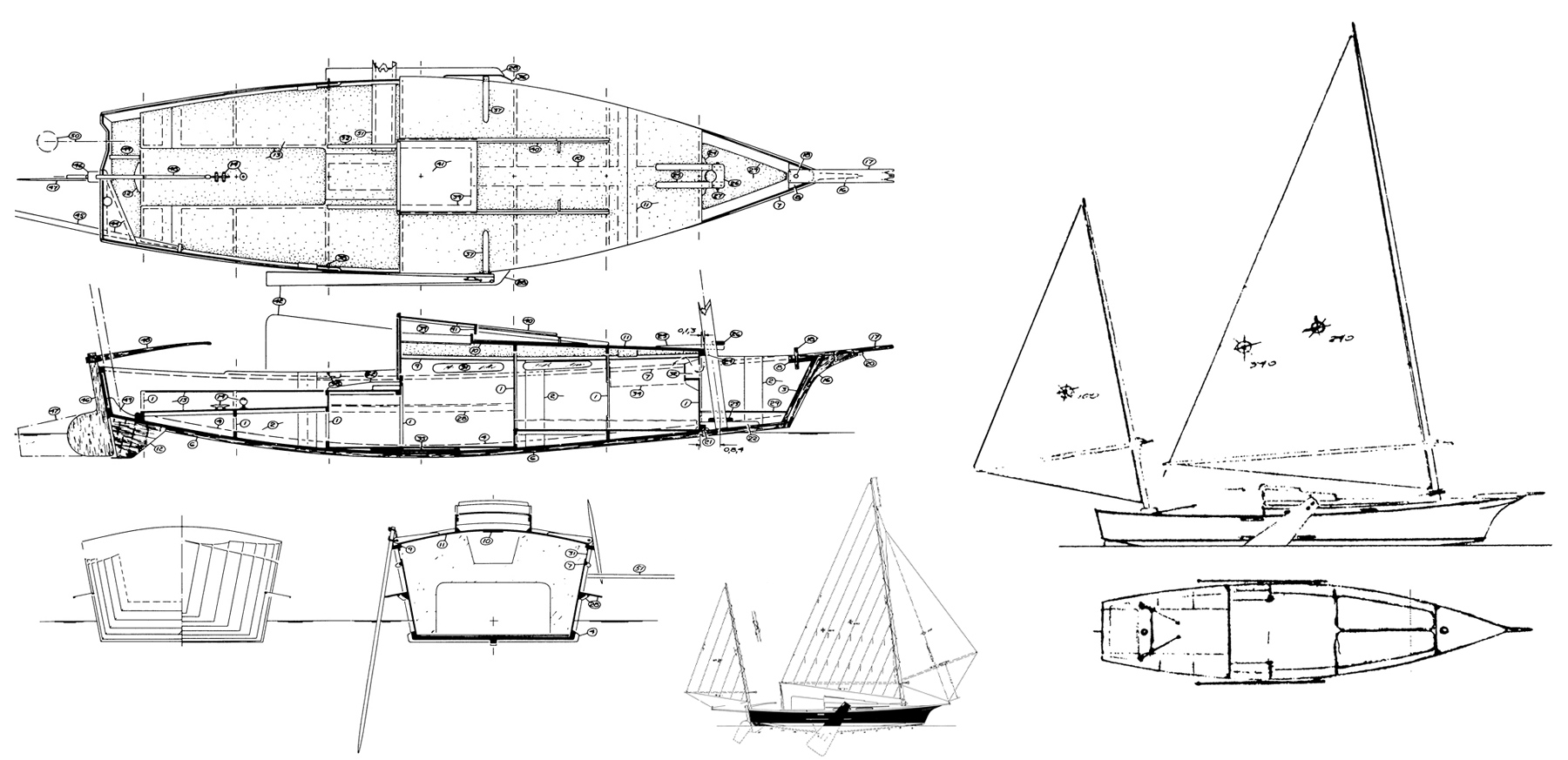

Skimmer’s construction plan speaks to her designer’s ability to engineer a strong and clean structure. A few bulkheads combine with longitudinal stringers and the plywood skin to produce great rigidity without the clutter of extensive transverse framing. Almost every element in the design adds to the boat’s strength. Sliding-hatch rails support the deck, and leeboard guards strengthen the sides. This rigid box-girder hull could winter on a knife’s edge without distortion.

We’ll assemble Skimmer in “Instant Boat” fashion. Bolger provides drawings that show the expanded shape of the sides—that is, the sides as if taken from the hull and laid flat on the shop floor. We re-create these patterns at full scale directly on the plywood sheets that will sheathe the hull. Then we cut out the sides and wrap them around the bulkheads and transom, which act as molds. True lofting and building jigs are not needed.

This is fast work for experienced hands and easy work for beginners. With the help of two friends, I assembled the hull in one 11-hour workday (after four days spent cutting and finishing various components). Get- ting the prototype completely built and ready for her maiden sail required a total of 700 builder-hours, but she went together outdoors between paying jobs. Working straight through inside a shop, 500 hours should be sufficient to produce a plain but fair facsimile.

How does she sail? Skimmer will match most stock cruising boats of her length when beating to windward; off the wind, she’ll reach and run many of them out of sight. To attain the surprising windward capability, the mainsail should be cut fuller and with the point of maximum draft farther forward than is common these days. Sew the mizzen flat as a bed sheet—this tiny (64 sq ft) swatch of Dacron provides control rather than drive. We’ll often want to strap that sail down hard and forget it.

Considerable tension in the mainsail’s luff is needed for windward work, and the halyard alone cannot supply it. If we attempt to haul on the halyard with too much vigor, we might put an alarming arc into the mast…but the luff still will be too loose. We need to fit a powerful downhaul with at least a 3-to-1 mechanical advantage. When setting the sail, first we two-block the halyard and secure its fall. Then we lay into the downhaul to get the luff taut. Before you argue that this explanation violates several laws of Physics 101, let me say that the key lies in friction and the severe taper to this unstayed mast.

Photo by Mike O'Brien

Photo by Mike O'BrienA simple flat-bottomed shape, inspired by historical sharpies, makes Black Skimmer simple to build in plywood.

Skimmer shares one weakness with many other flat-bottomed sharpies. She does not like sailing in very light air and a slop leftover from the afternoon sea breeze or powerboat wakes. Here, a large headsail might help. The inverted “kite” sail headsail sketched on the plans never worked well. Perhaps a single-luff spinnaker….

This sharpie has no handling vices. Her off-the-wind manners in a stiff breeze and steep sea are comforting. When other monohulls begin their annoying, if not terrifying, rhythmic downwind rolling, Skimmer is rock steady. A powerful rudder and skeg combine with ample rocker and a shallow forefoot to make easy work of it. The self-vanging sprit booms help by reducing sail twist. And that rudder combines with the large leeboards and substantial rocker (with occasional help from the backed mizzen) to ensure reliable tacking. During my 10 years of sailing this sharpie, she never got caught in irons…not even once.

A professional builder should be able to deliver Skimmer for about the same price as a stock 22′ fiberglass cruiser, and she can be home-built for about half that cost. Whether or not that makes for a good investment depends, among other factors, upon how long and how well she’s kept—and upon the availability of buyers who agree with the words you’ve just read. ![]()

A preliminary “cartoon” proposed dual rudders allowing the mizzen mast to be stepped on the centerline. For simplicity, the author favored a single rudder; Bolger’s solution was to move the mast aft, hard against the transom and offset to starboard. Black Skimmer’s accommodations are rather spartan but unimpeded by a centerboard trunk thanks to the use of leeboards.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2010 and appears here as archival material. If you have more information about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Beautiful boat to my eyes! and you have the perfect place to sail her! Reminds me in so many ways of my Bolger’s Birdwatcher.

Why is the Dovekie designed by Bolger and built by Eddy and Duff not part of this article? The two boats are strikingly similar. Everything mentioned in this article pertains to the Dovekie! Peter Duff would not be pleased.

Bill Stocker, former Stonehorse owner.

The review of the Black Skimmer first appeared in Small Boats 2010 and material for that issue was gathered in 2009. In that same year Phil Bolger passed away and Edey & Duff closed following the unexpected death of the company’s general manager; the Edey & Duff Dovekies were no longer available.

Second hand Dovekies are still available. Yes, Edey and Duff closed after the sudden death of David, their general manager. His death was preceded by Peter Duff’s death after a long struggle with Parkinson’s disease. Peter had a close relationship with Phil Bolger. They were both proud of the Dovekies built by Edey and Duff. Black Skimmer’s description is exactly the same as that of the Dovekie. I think readers would appreciate the history of this unique design by Phil Bolger.

I will certainly investigate this as well as the associated boats. This seems the ideal to me but I have more info to gather. Not sure I have room yet to build but sure I can find it. I need a place to find all of Mr. Bolger’s ideas and designs. One of the many geniuses we have been blessed by in so many realms.

In many ways Birdwatcher is a better boat than Dovkie, and fulfils the same design objectives. Plus, it’s designed for home building.

Hi guys,

Thanks for the article on Black Skimmer. I need to mention a predecessor, however. Way back in the Dawn of Time, 1960, at Mashnee Island (at the Head of Buzzards Bay) I used to sail my small boat by a strange winged creature which turned out to be Black Gauntlet. She was longer than Skimmer, maybe 30+ feet. It had been built nearby at Bucky Barlow’s yard in Pocasset (The Home of the Meadowlark). Peter no doubt did much of the work and the details and later while sailing other boats and knowing Mait Edey I crossed paths with and cruised occasionally with Peter Duff and BG. She was fast and spirited. Peter usually left the “Potato Chip” mizzen up at night to keep the boat from yawing around at anchor. I can say she was a bit noisy if the waves in the harbor were more than 0.5 inches with that bow out of the water, while the Meadowlark is silent. Those were some great days of adventure and experiment.

Bob Wallace

Am in infested in the Skimmer. Who sells plans and is a kit available?

Plans for Black Skimmer are available from http://www.Instantboats.com , Harold “Dynamite” Payson’s website. I sailed a Black Skimmer for a week’s charter across Florida Bay from Key Largo to Everglades City, down to Lignum Vitae Key and back to Key Largo. Handled beautifully, just as Mike says in the article. There was ample room inside for sitting and kneeling headroom (I’m 6’2”, my wife is 5’11”), a porta potti, a camp stove, and a roomy double berth forward.

I built two small Bolger boats, Teal and June Bug, and corresponded with and spoke to Bolger and Payson both. I have several of their books in my library and the letters will be filed in them.

I chartered a Black Skimmer at Key Largo for almost a week on Florida Bay over 30 years ago. It was a perfect match: thin boat for thin water.

How much headroom inside the cuddy or forward section? Nice design,

Thanks

Jim

I also chartered a Black Skimmer (three times) in Florida Bay and still think of it often, even thirty years later. I believe one of the chartered boats was the original Skimmer. Wonder where they are now?

Hi,

Yes, I chartered the red one. Great fun. The black one ended up in a restaurant parking

lot as a road side attraction on the 1A. If I was to guess, mile marker 45 ? Back in early ’90s.

I saw the article about Black Skimmer in the Small Boat Journal (or was it WoodenBoat? I don’t remember which) long ago. I lusted over that boat for years. But living in the Chicago area I couldn’t justify building one. Then the successor design, Martha Jane, appeared. Allegedly a Black Skimmer modified for easier trailering.

After moving to Florida I built, sailed and loved the Martha Jane. She was snub-nosed, a bit shorter, and had a balanced lugsail with a shorter mast mounted on a tabernacle. She was supposed to be water ballasted. I had my drill bit poised at the chine to drill the hole for the water ballast and couldn’t make myself do it. Water inside a wooden boat didn’t seem like a good idea. I filled the tanks with 500 lbs of solid ballast.

Early on, we discovered the flaw. With the 200 sq ft mainsail luffing and the small mizzen cleated we were hit by a shifting gust of wind, maybe 40 mph and knocked flat. I thought she’d self-right but instead she turned turtle and we had a terrible time.

Mr Bolger decided that there was a problem and designed a “fix” which included sponsons, 500 additional pounds of ballast and optional “high house” (which I didn’t add because of windage concerns.)

The modified design also included dual shallow-draft rudders. Now the boat was an absolute delight. I miss her to this day.

She was noisy at night when anchored, even small little ripples seemed magnified inside that huge interior. But I still loved that boat. Of all I’ve owned, she the favorite.

So glad to see this article. Around Christmas, 2021, I found a blurry image of a large boat on Craigslist. Only $1000, which appealed to my Scots ancestors! Turned out it was a Black Skimmer, built in 1982, but not in bad nick at all. So I bought it.

Since then I have been working on it. The first thing I found out was that it was unacceptable without a private potty, so with the advice of The Nomad Boatbuilder I decided to lengthen the cabin by about 30 inches and its height by 7 inches. Hard to get a private head into a 4 foot cabin. So far things are going well, but the proof of the pudding will be in the eating.