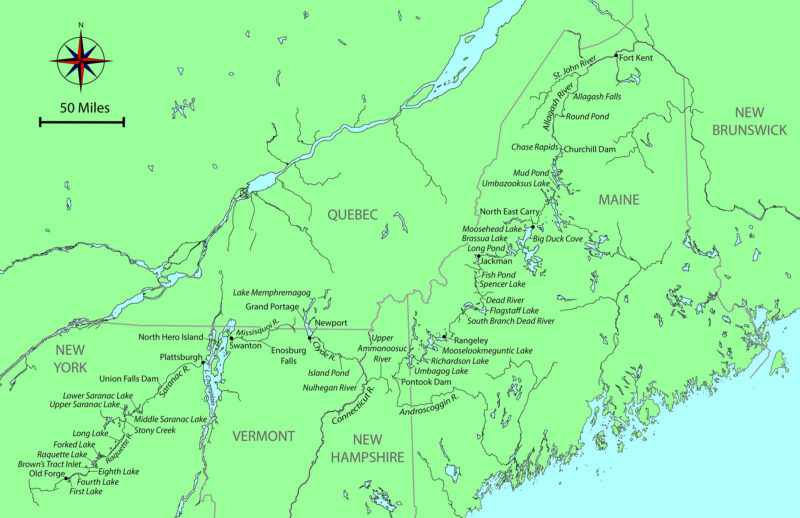

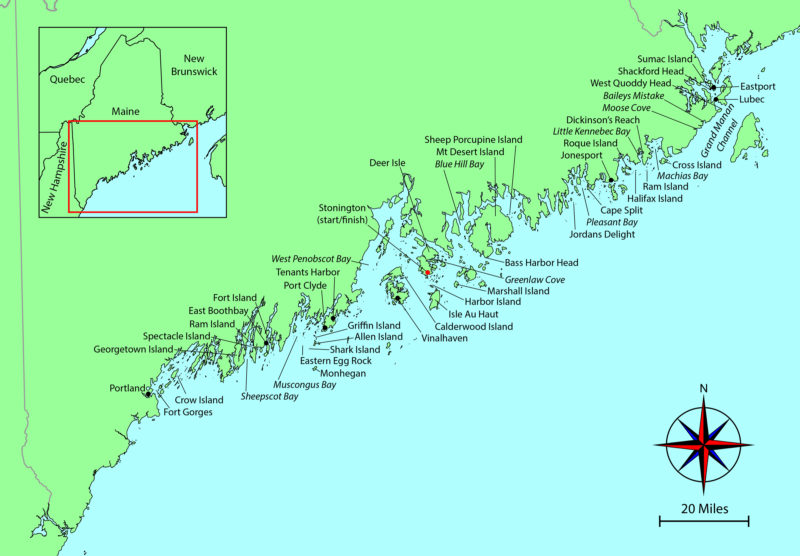

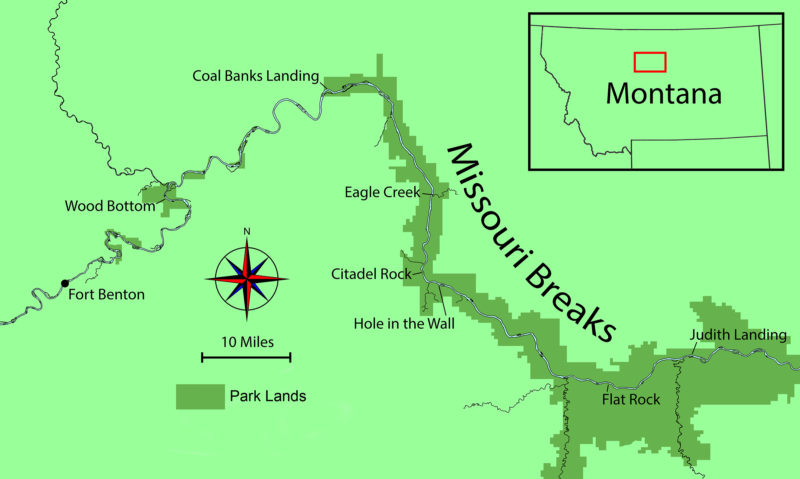

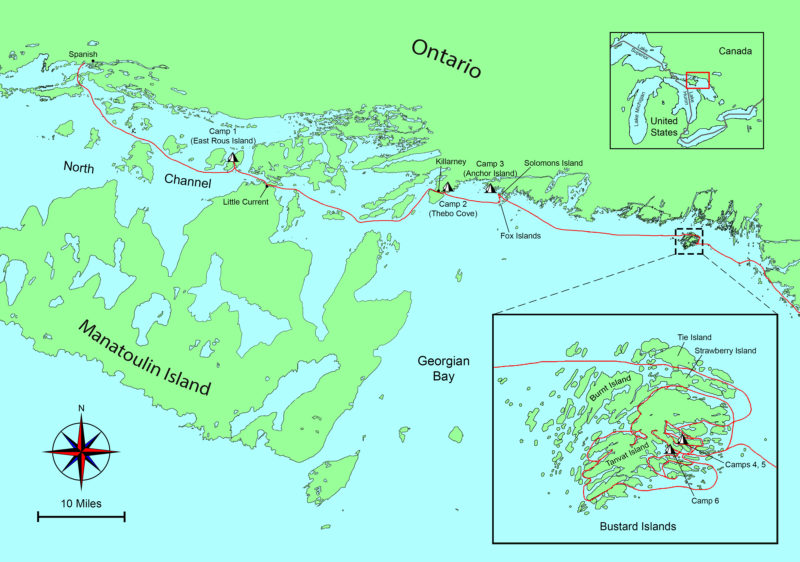

Our plan was simple: on Friday, April 30, 2022, Delaney and I would embark from Brooklin to make a 26-mile circumnavigation of the southern end of Maine’s Blue Hill Peninsula by way of Blue Hill Bay, Blue Hill Falls, and the Salt Pond and Benjamin River with a half-mile haul between the two along what once was an old Wabanaki portage. We were hoping that if we worked hard, we’d be able to make it back to Brooklin in three days, camping along the way on Long Island in Blue Hill Bay and at the Reach Knolls campground at the mouth of the Benjamin River.

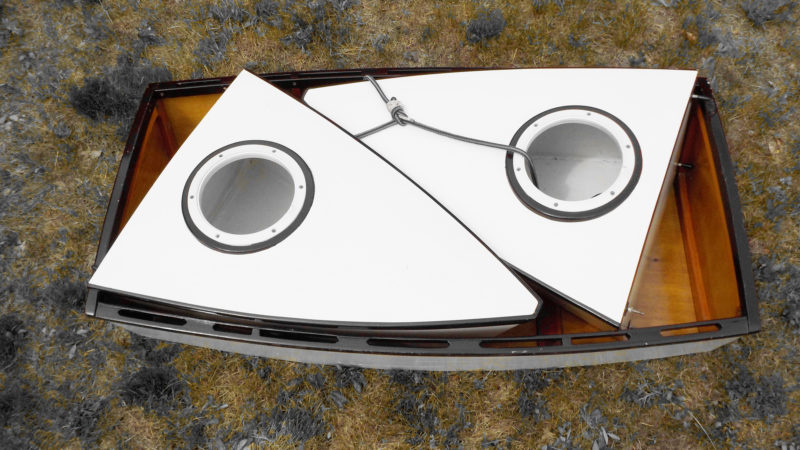

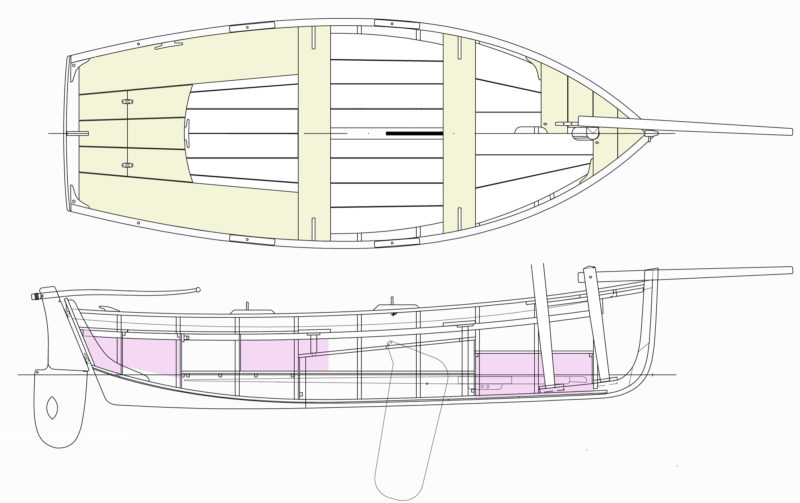

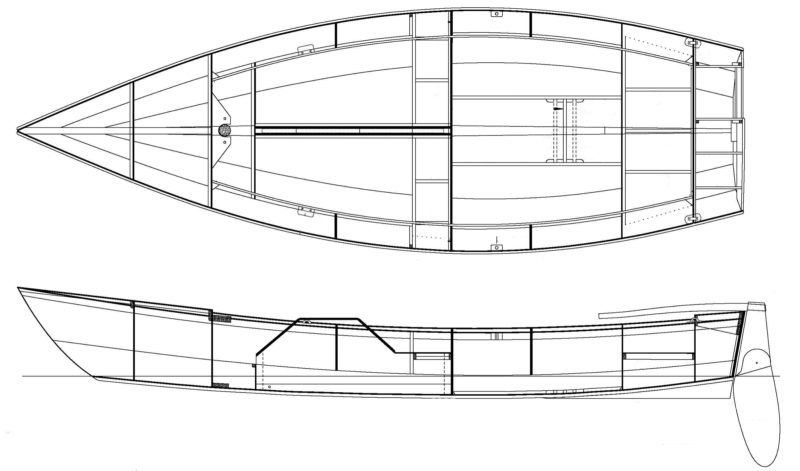

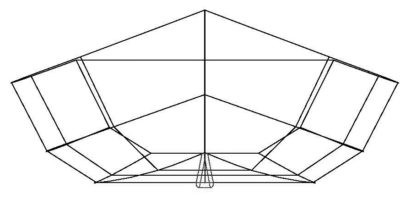

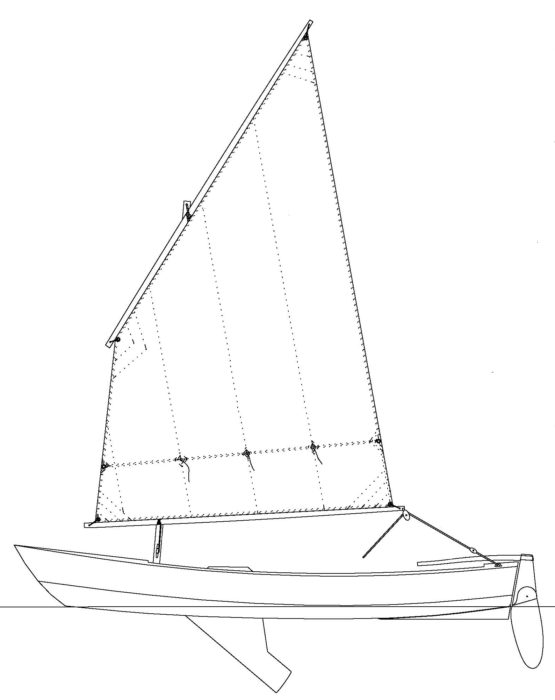

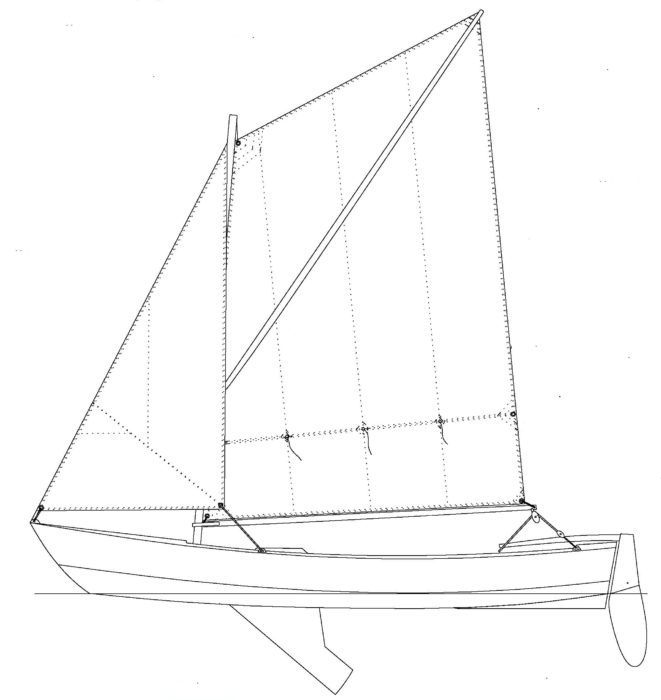

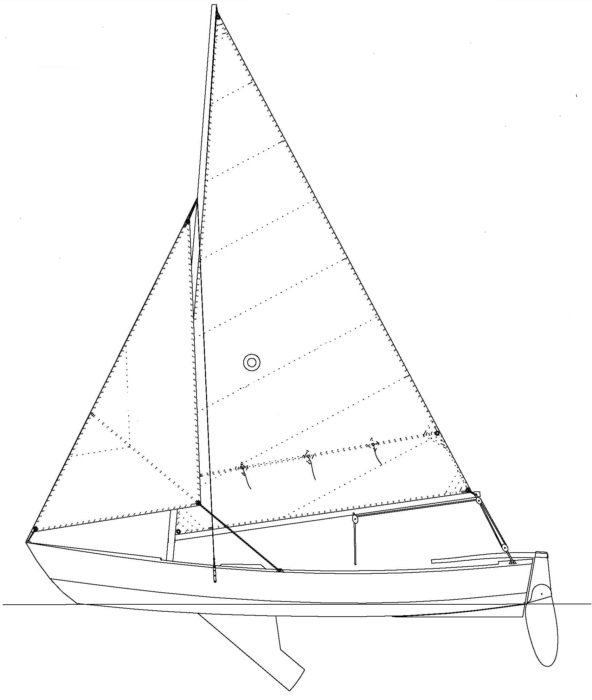

The trip was conceived only a week earlier as Delaney and I stood in my parents’ garage in Worcester, Vermont, and looked at the 17′ Chesapeake Light Craft Northeaster dory my father and I started building in 2014 in a one-week class at WoodenBoat School. He and I thought it would be a boat I could cut my teeth on for boatbuilding and rowing, but we had never finished it. Since the class it had been languishing in the garage for eight years. WHISTLER—as we named the dory for my propensity as a 13-year-old to whistle while building it—looked forlorn as I ran my hands over the dusty hull, but all it needed to be ready for the water was interior paint and varnish on the rail.

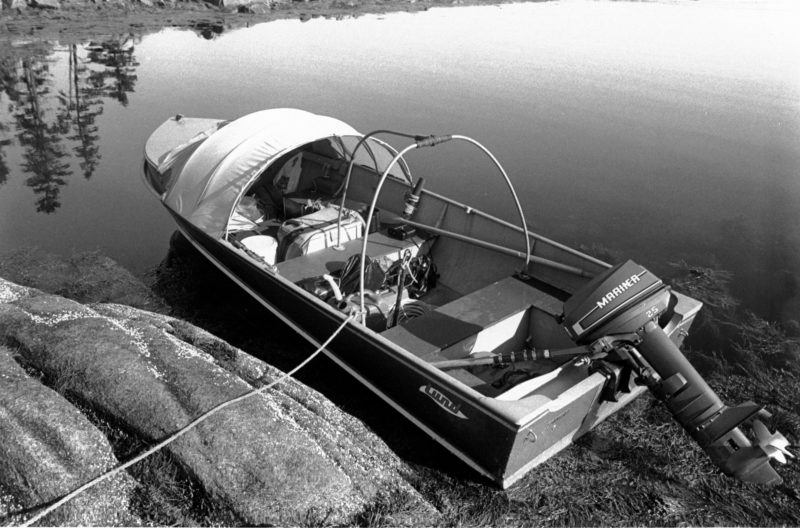

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Last year, while working at WoodenBoat School, I’d heard the stories visiting Grand Canyon river guides had told about running dories through rapids, and while WHISTLER is a different kind of dory, I imagined running the Blue Hill Falls tidal rapids at the entrance to Salt Pond. Delaney liked the idea of running the rapids and taking on the circumnavigation, and we decided to cartop the boat, take it with us back to Maine, and get it ready to launch.

We worked on the boat in the shop at WoodenBoat the following week, and by Friday morning the paint and varnish we’d applied had dried. If we were going to do the circumnavigation, we had to start that day, as that last weekend in April was the only time we’d have together for several months, and the tides were perfect. The only problem: the wind was blowing 20- to 35-knots from the north, the worst possible direction for our row from the launch ramp at WoodenBoat School. Still, we were determined, until a small-craft advisory finally convinced us that launching to take on a 12-mile row from Brooklin to Blue Hill Falls would have been not only ill-advised but also rather dangerous. The new plan was to launch on Saturday from the South Blue Hill boat ramp 1-1/2 miles south of the falls.

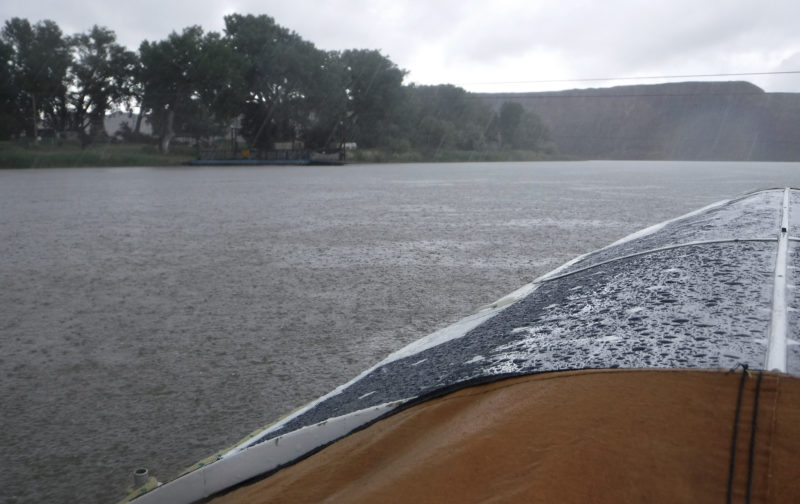

By 8:00 Saturday morning, Delaney and I were at the oars, bashing WHISTLER into steep swells. I was at the forward station, with Delaney at the aft thwart; we struggled against a 15- to 20-knot wind on Blue Hill Bay. The bow rose over a rolling 2′ wave and when the flat bottom slammed hard into the trough, I felt a painful pinch in my lower back as it compressed. A 20-knot gust brought us to a stop and tugged at my oars even though I had the blades feathered. Each stroke moved us forward only a few feet before WHISTLER butted against the next wave.

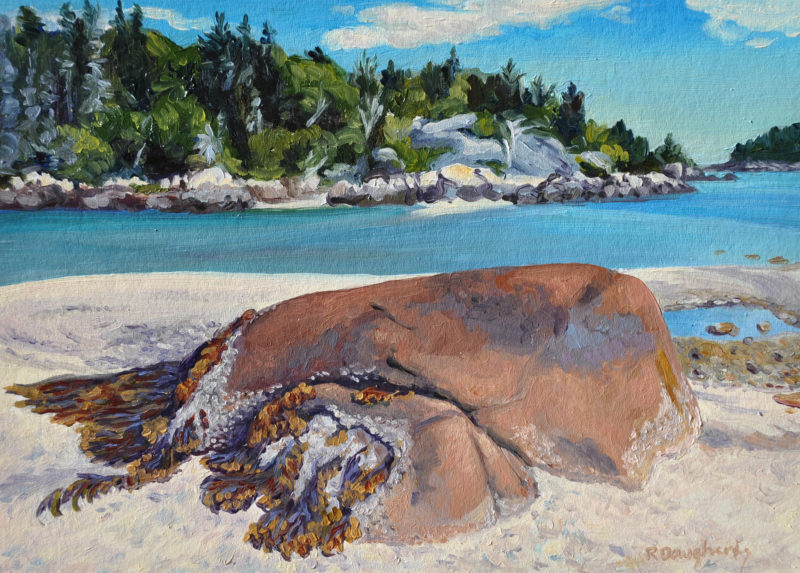

I could feel the burning in my forearms even though we had only made it ¼ mile under the steel-gray skies and whistling wind. “Need a break?” I shouted to Delaney. “Not a bad idea,” was the reply, and I turned us toward a patch of beach 50 yards to port with the promise of a calm resting spot drawing us in. We beached on a bed of baseball-sized rocks covered in dark green seaweed and dragged the boat out of the water so it wouldn’t get beaten by the knee-high swell breaking on the beach.

Photographs by Delaney Brown and Tom Conlogue

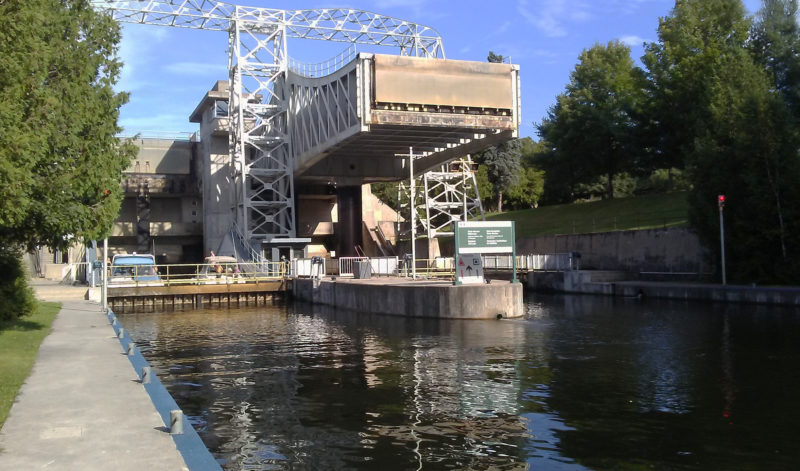

Photographs by Delaney Brown and Tom ConlogueAfter backing WHISTLER onto the beach, we did a reconnaissance run to the bridge to scope out the falls. The north end of the Blue Hill Falls bridge is visible above the dory’s aft thwart.

We sat on a smooth, waist-high boulder, watching the whitecaps roll by for five minutes, and caught our breath before pushing back out into the grim, green-gray water, white streaks trailing from the wave crests. I took short tugs on the oars to get us moving as Delaney shoved off and boarded over the stern. My oar blades dragged through mats of tangled seaweed until we were two boat lengths from shore. Delaney settled on the aft thwart, slipped her oars out through the locks, and we fell back into our rhythm, working our way to windward at barely over 1 knot. We stayed 30′ from shore, away from the waves as they steepened and crested in the shallows but somewhat protected by the land. Spray flung by the diving bow pelted my back. The water was loud on the hood of my jacket, ran down my back, and pooled around my feet to slosh back and forth between frames.

Delaney’s port oar dug in suddenly, as a wave crest caught the blade and sent it diving for the bottom. The grip was almost wrenched out of her hand as it tried to push her off the thwart. The oar dragged the bow around to port and we were no longer pointing into the wind. As the dory veered toward shore, I quickly pulled hard on my port side to correct our course while Delaney freed her oar from the water. A few strokes later it happened again, on the starboard oar this time. “I’m going to count how many strokes I can get in a row without catching a crab!” she yelled and began counting aloud as we continued to row. With Delaney chanting her stroke count aloud, we laughed every time she had to restart and cheered when she reached a new high score of uninterrupted strokes. After we had rowed for a half hour, I looked over my right shoulder and saw the sandy-gray arches of the Blue Hill Falls bridge, and we made for a beach just south of the bridge.

Blue Hill Falls is a short stretch of reversing tidal rapids at the entrance to Salt Pond. Four times a day water pours through the 100′-wide gap beneath the bridge, creating standing waves as the tide floods into and ebbs out of the 3-1/2-mile-long pond. While the safest way through is to wait for slack water, we had decided to go through at the peak of the flood when the current would be strongest and the rising tide would significantly shorten the portage at Salt Pond’s far end.

After beaching the dory and taking a quick water break, we walked over to the bridge to see what we had gotten ourselves into. After clambering up the scree slope at the side of the road and walking to the middle of the bridge, we looked down over its Salt Pond side at the flood tide’s standing waves. My worries about getting capsized instantly evaporated. While the rapid was moving fast, it wasn’t nearly as turbulent as I had remembered. On the north side, the water ran smooth and black under the bridge before plunging into a train of 3′ standing waves, but on the south side there was a straight shot through with only the occasional riffle disturbing the surface.

“This isn’t going to be nearly as exciting as we thought, is it?” Delaney said. “What do you think, should we go straight down the middle?” I replied, “Yep, let’s hit the medium-sized waves.” That approach would avoid the extremes, either too rough or too smooth. We climbed back down the rocks at the end of the bridge and walked gingerly among the softball-sized rocks along the shingle beach to the boat. We pushed off under a sky overcast with low steel-wool-gray clouds and maneuvered stern-first into the current upstream from the bridge.

Delaney took her seat and braced her feet on the sternsheets, and we let the dory get carried under the bridge. As WHISTLER picked up speed, the water turned from gray to dark green as it piled up on the bridge’s concrete footings on either side of us and funneled us through. Pulling occasionally on the oars to keep the stern pointed in the right direction, I steered us in between the fast, clean water off the starboard beam and the tumbling standing waves off the port beam. Below the bridge, we gently rolled over a smooth crest, then rose up the far side and crashed down. Looking past Delaney’s shoulder I saw just a tongue of water lap over the transom, and then we were past the waves and into the pond.

Choosing to take the middle route down provided a smooth ride, although in hindsight the line on the north side of the rapid would have provided a sportier experience.

Just past the Blue Hill Falls bridge, visible at the far right, and onto the Salt Pond, Delaney provided directions and encouragement while I enjoyed the easy rowing, good view, and occasional warmth from the sun.

In its narrow entrance, the wind was calmer and with the sun coming out we needed to peel off some layers, so about 500′ beyond the bridge, we cut diagonally across the current and made our way to the beach. After we took off our spray jackets, we pushed back out and rowed across the upstream current of a back eddy where leafy seaweed on the bottom waved gently toward the bridge. When we reached the main current, it again carried us southwest. Delaney moved to the sternsheets to take a break and watch the scenery slide by as I rowed us down Salt Pond with the wind and current nudging us along at an effortless 4 knots.

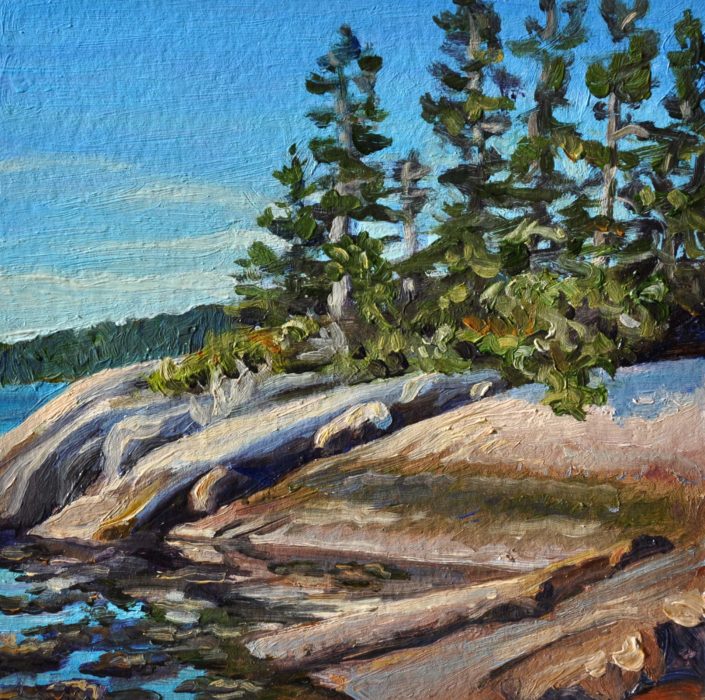

A half mile farther along, we skirted a rounded granite boulder that splits a channel where the pond narrows from 1/5 mile to just 80 yards. A half mile farther we saw a field of buoys ahead, arranged neatly in long rows 20′ apart. At the first buoy, Delaney peered over the side into the water at the fuzz-covered ropes hanging straight down and disappearing in the olive-green murk. “Mussels?” she wondered out loud; I shrugged. She did a quick Google search on her phone, which revealed it was indeed a shellfish farm, growing oysters as well as mussels.

By noon we had made it to the head of the Salt Pond, where it turned into Meadow Brook, a channel 10′ wide with grassy banks on both sides. We had timed it perfectly, and arrived at high tide, but the brook was still too narrow for the oars. We climbed out and used the bow and stern lines to guide WHISTLER up the winding stream, our boots crunching softly over the dead grass on the bank.

Nosing up to Meadow Brook, the channel became shallower and we dragged the dory over submerged rocks while avoiding the visible ones. The guardrail of the Hales Hill Road bridge was within sight, beyond the large boulder in the distance.

The brook quickly became too narrow for rowing, so Delaney and I hopped out and lined the dory up the last bit of the way to the beaver dam.

After navigating six bends in 60 yards and crunching the boat on a few submerged rocks, we were at the Hales Hill Road bridge. Its cement slab, supported by stacked rough-hewn stone blocks, spanned an opening just 6′ wide—barely enough room for the boat—and 4′ high, too low for us. The water running through the culvert was more than boot deep. Delaney scrambled up the embankment and crossed the road to the upstream side of the bridge, where she stepped over the metal guardrail, pushed through chest-high raspberry bushes, and poked her head and an arm over the edge above the water, ready to catch the boat. I gave WHISTLER a shove. The boat coasted smoothly upstream through the culvert for a few feet, before veering to port toward the rough-edged wall. Dangling as far out as she could without falling into the stream, Delaney grabbed the breasthook and saved the newly varnished rail from making contact with the rocks.

The water flowing under the Hales Hill bridge was especially deep, so we shoved WHISTLER through unmanned.

Just 50′ upstream from the bridge, we came to a 3′-high beaver dam of tangled twigs flanked by thick brush. Rounded granite boulders scattered around the dam had tan-colored bands marking the water level when the dam had been about 1′ higher. We had brought two large fenders to use as rollers for just such an obstacle as the dam and deployed them for protection from the rocks. We scooted WHISTLER safely over and into the still, pooled water upstream. Delaney crawled over the transom and stood up forward with an oar in hand, and we paddled canoe fashion up the beaver pond.

The rollers that we brought with us helped us clear the beaver dam with little struggle. Beyond the dam, the water was deep and clear, making the paddling easy.

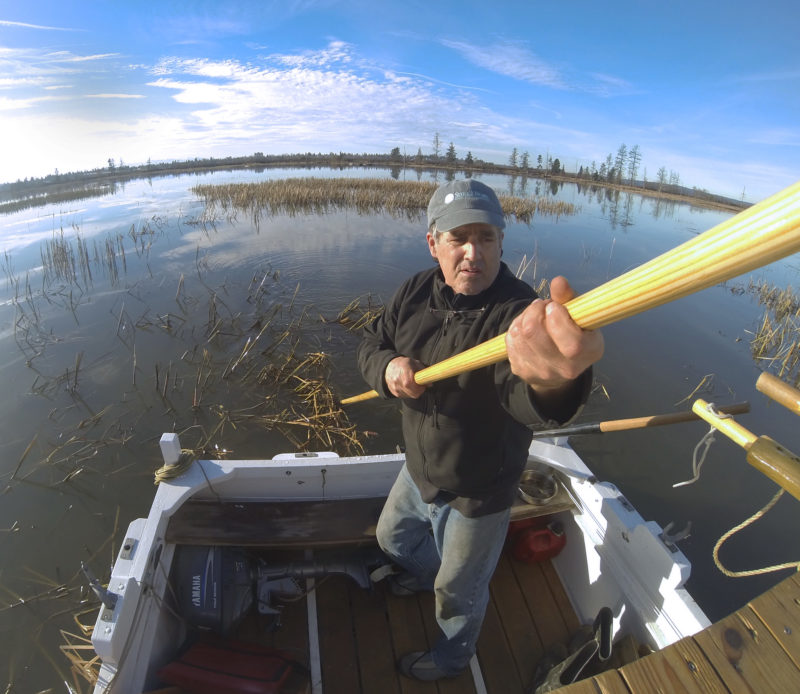

As the water got shallower, poling became the only way to move forward. Despite the common knowledge that you should never push off the bottom with the blade of an oar for fear of it splitting, the width of the blade proved less susceptible than the handle to sinking into the muck below.

The smooth going was short lived. After only two minutes of paddling, the skeg started to drag in the mud below. We decided the best option was to drag the boat over dry land toward the tree line 1/4 mile away, and Delaney leaped from the bow for the streambank and landed on a tussock of grass. I thought she had made it, but then the tuft sank under her, and she splashed down into knee-deep water with a howl as her boots quickly flooded. She scrambled for firmer ground and eventually found a piece of grass that did not sink immediately. She stood up with a scowl.

I poled the boat a few more feet until the bow was nestled in grass, then gingerly stepped over the rail onto a firm-looking patch of grass. It shifted unsteadily below me. I knew we had to get the boat to firmer footing if we were going to drag it any farther. I braced my feet against two tussocks, grabbed the breasthook, and pulled firmly. The boat lurched forward no more than 1′, and then came to a halt with the screech of dry grass on paint.

From where we had run aground, it was a half mile to where satellite images we’d studied seemed to indicate the portage should have started. Realizing that we clearly were not going to make it to the Benjamin River that day, our new goal was to get the boat to the portage before dark. It was only 12:30, and that seemed like a realistic goal.

Abandoning what was left of the main channel, I began dragging the boat toward the tree line, hopping from one tuft of grass to the next to avoid the deep puddles scattered around them.

Getting ready to schlep the gear to lighten the boat, we took a quick break to feel sorry for ourselves before beginning the first long trudge to the tree line.

I began unloading some of the heaviest items: Delaney’s duffle, the cast-iron skillet, two 1-gallon jugs of water, and my dry bag backpack full of food and camping gear. Delaney worked her way toward me, lifting her legs over the tussocks and pushing through the chest-high grass, falling with almost every other step. Loaded down with gear, we scrambled toward a point in the tree line 1/4 mile away where we would stash everything and eat lunch before coming back for the boat. As soon as we set out, we knew we had made a mistake. What had looked like drier land was in fact just more tufts of grass, surrounded by water. Stepping from one clump to the next, I crushed each tussock down, throwing my balance off and sending me stumbling. Water poured into my boots, and thick mud beneath the water threatened to pull them off. My clothes were damp and sticky and my back prickled with sweat.

In most areas the grass reached Delaney’s chest. As we headed back to the boat after lunch, she gave me a distinctly displeased look amid the expansive grassy landscape.

Delaney, whose legs weren’t long enough to step up on the tussocks, slogged through the mud and water while carrying a gallon jug of water in each hand. Every few steps she fell from one puddle to the next and disappeared behind the tawny grass, but somehow remained smiling. By the time we had made it to the firm, dry ground at the tree line, it was 1:15. The carry with our gear had taken us 45 minutes to traverse a quarter mile, and we hadn’t even brought the boat.

Delaney crawled into the trees leaving a trail of wet socks and spray gear. I pulled a wool blanket out of the duffle and stretched it out on some moss amid the trees, then made BLTs from homemade bread and Delaney’s favorite vegan bacon. Munching on my sandwich, too hungry to care about the fake meat, I looked out over the expanse of undulating golden grass, and my optimism began to increase. “This ain’t too bad after all,” I said, looking at Delaney. She offered a half smile, and I noticed she was shivering in the light early spring breeze blowing through the trees. I scrambled over to my backpack and pulled out the space blanket I had stashed for just such an occasion. She lay down on the wool blanket, I spread the space blanket over her, and tucked the upwind side under the backpack. I curled myself around her back; the shiny silver rustled over our heads. Through chattering teeth, she cheerfully said she would warm up in no time.

Ten minutes later, her shivering hadn’t stopped. “Time to move,” I said. Delaney grumbled but got up and put on her wet spray gear and socks as I packed up our gear and piled it by the edge of the trees. To warm us both up, I set a brisk pace back to the boat; soon we were both sweating again, and once she started cursing again I knew she would be okay. After reaching WHISTLER what seemed like hours later, we sprawled in opposite ends of the boat while we caught our breath. “This may have been one of the worst ideas I’ve ever had,” I said, feeling bad for dragging her on this adventure. “Maybe make the next one an easy trip?” she offered, and we got ready to drag the boat.

It was slow, brutal work. With me pulling and Delaney pushing, we moved the boat only 2′ at a time before it came to a halt or one of us fell into the mire. The sharp bottom edge of the breasthook dug into my hands and the grass under the boat turned from gold to black as it was crushed into the water. Working slowly, we inched toward the tree line, leaving a dark scar through the brush behind us. The effort made my arms burn and left me panting.

A little over an hour later, we made it to the trees. Gasping and saying little, we unpacked the last of the gear and looked for a place to set up the tent. Even though it was only 5:30 and there was plenty of daylight left, this was as far as we were going for the day. We were completely burned out and needed to get out of our wet clothes before we got chilled. We found a flat spot in the trees, and pitched the tent; I crawled inside, lying face down with the warmth of the smooth nylon sleeping bag tempting me to sleep. Delaney joined me, using my back as a pillow and we remained motionless for a while, waiting for our strength to come back so we could make dinner.

At the beginning of the day, while we were launching WHISTLER at the boat ramp, we had met a lobsterman who, after hearing our plan, had invited us to stay on his land if we didn’t make it as far as we hoped. His only direction had been “on the left beyond the bridge at the end of the Salt Pond.” We were unsure if we were in the right spot, but we started gathering wood for a fire, hoping this piece of the woods we had found was on his property.

I kicked loose leaves and grass to the side and made a fire ring of soggy logs, and soon the warmth of the leaping flames provided a welcome relief from the chill of my damp clothes. We heated up dinner, an Indian rice affair, in a cast-iron skillet and scarfed it down as the dark crept in steadily. Fed, watered, and starting to warm, we sat by the fire for hours, socks spread around the flames like fallen flower petals. Around 10 p.m., Delaney did an especially jaw-cracking yawn, so we extinguished the fire and moved into the tent, with the pleasant scent of wood smoke clinging to us like an earthy perfume. In the dark, above the tent’s mesh panels, the sky had cleared to a kaleidoscopic view of stars, and we fell asleep to the sound of spring peepers.

I woke up late the next day, and, gingerly testing my muscles, was surprised to find I hadn’t locked up overnight. The weather began as the day before had with low puffy clouds, with occasional breaks that let the sun through. We packed up and were ready to get underway by 10:30, keenly aware of our dwindling time. Trying something new, we used two fenders as rollers, sticking as close to the tree line as we could where the ground was dry and the going a little easier. Delaney placed the fenders under the bow and pulled while I pushed and threw the fenders forward when they slipped out the back. It was slow going because fenders refused to roll over the hummocks and the dory bottom dragged across them. “Do you think we need these things?” Delaney asked, after half an hour of wrestling with the fenders. We threw them into the boat and dragged it, Delaney leading the bow with the painter while I pushed the stern.

It was a dramatic improvement. Compared to the day before, the sliding was much easier on the dry grass, and we could make it a full 10′ before I ran out of breath and had to take a break. Two hours later, after stopping for a half-hour lunch break in the trees, we had covered a quarter mile. We left the boat next to an abandoned cow pasture and walked up the remaining distance along the edge of the trees to where the portage proper should have started. It wasn’t good. Branches were tangled together in a thick wall and the trees were clustered close together; while a portage was definitely possible with a canoe or kayak, WHISTLER was far too wide to squeeze though. Our options were to go back the way we came, or try to cut up over to River Road, a quarter mile to the southeast.

Delaney led WHISTLER like a recalcitrant mule toward the cow pasture. As the ground evened out, it became easier to move the boat without the rollers and rely on strength and stubbornness.

Since retreating over the difficult ground we’d already covered was not an option—we had run out of time—we walked up the cow pasture toward the road, hoping to find a house with someone friendly enough to let us bring our car to pick up the dory. Walking up a gravel access road off one of the pastures, we strolled past a spent 12-gauge shotgun shell on the ground. Apparently, this was an unusual sight for a Florida girl, and Delaney grabbed my arm. “We’re going to get shot!” she said. “Relax,” I replied, “Most people at least have the courtesy to ask who you are before they shoot you.”

We crossed River Road and walked up to a farmhouse perched on the top of a hill, where a couple in their mid-forties were more than happy to help, insisting we have a drink of water before giving us a ride to our car.

Delaney and I drove back to the cow pasture and threw gear into the car. When we rolled WHISTLER over to lift her onto the roof rack, twigs and grass poured out. The bottom of the boat was scarred where rocks had cut through the epoxy, graphite, and fiberglass, and the topside paint had long pale streaks from brush dragging along the side.

After securing permission from the property owners to bring our car to their field, we faced the last challenge of the trip: hoisting the 100-lb dory onto the roof rack. Delaney apologized to WHISTLER for the rough treatment. At the beginning of this adventure, the hull didn’t have a scratch on it.

We had done only about 6 of the 26 miles of the circumnavigation of the Blue Hill Peninsula we’d set out to do, but we’d had more than our fair share of adventure. We might have made the whole loop if we’d had more time, or a more friendly weather forecast. We had underestimated the difficulty of hauling a 17′ dory to an ancient and inaccessible portage, and if we had done a little more reconnaissance, we might’ve known what we were getting into. But we had made an attempt, and managed to have a good time and keep each other going even while doing something that couldn’t be done. ![]()

Tom Conlogue is a former WoodenBoat School waterfront staff member who is currently feeding a crippling boat addiction as a student at Maine Maritime Academy. He can usually be found near some patch of water messing about in small boats.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.