photographs by the author

photographs by the authorMud flats don’t invite strolling, so with a pair of pattens you can have the intertidal all to yourself. A staff is a useful accessory for checking the depth of mud and water and maintaining balance.

When I rowed down the Ohio River, mud was something I had to deal with almost every day. It was the consistency of vegetable shortening and often as deep as my rubber boots were high. Ferrying camping gear from the boat to shore in the evenings and from shore to the boat in the mornings was an arduous process. I would have had an easier time of it if I had known then about mud pattens that waterfowlers use on the mudflats surrounding shoal inland waters along England’s southern coast.

If you’ve read Arthur Ransome’s book, Secret Water, you may remember splatchers: “two large oval boards, with rope grips in the middle of them for the heel and toe, and stout leather straps for fasteners.” Ransome’s drawing of them shows them about twice as long and twice as wide as the soles of the boots of the boy who is wearing them. I once improvised a pair of splatchers with driftwood and rope, and didn’t get far on an intertidal mudflat before I found myself stuck. Both splatchers were so firmly held by suction that I had to cut my feet out of the rope bindings to escape.

Boots alone sink into the mud, and suction can sometimes pull them right off your feet.

Mud pattens have been in use for centuries and are effective for walking on mud. They’re squares of wood or plywood with three cleats on the bottom, and two loops of thick rope on top. A separate length of lighter rope binds the thicker rope over the boot heel and instep. It’s best to use line that is not slippery, such as nylon, so the knots don’t loosen. I use manila; it has a coarse texture and stays tight.

Pattens distribute weight out over a larger area to minimize sinking. The positioning of the ball of the foot at the edge of the patten is what makes it possible to break the suction.

I made my first two pairs of pattens 12″ square, a common size in England. They can vary in size according to the softness of the mud and the weight of the wearer. I made my third pair 14″ square, and it’s a better match for my 220-lb frame.

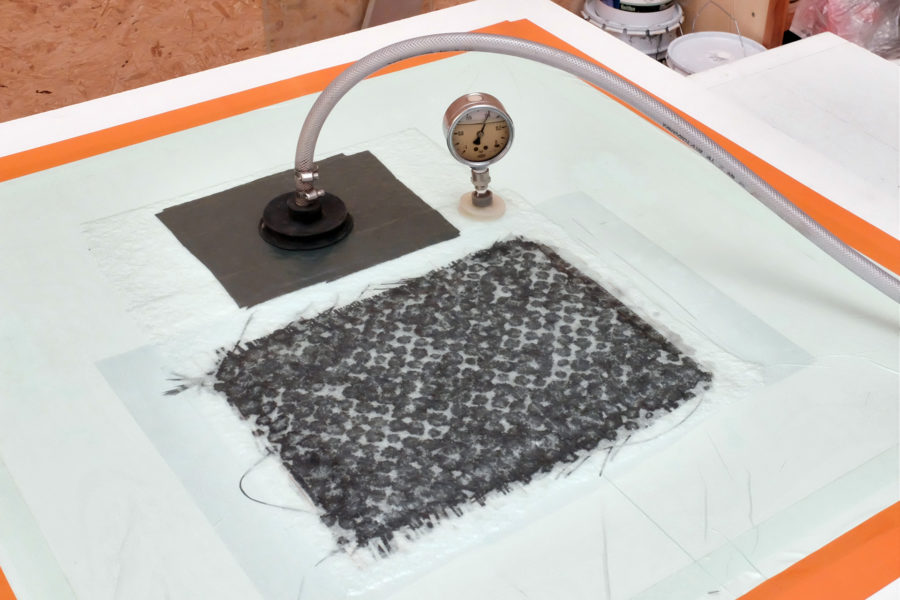

Cleats on the bottom add strength and traction to the pattens.

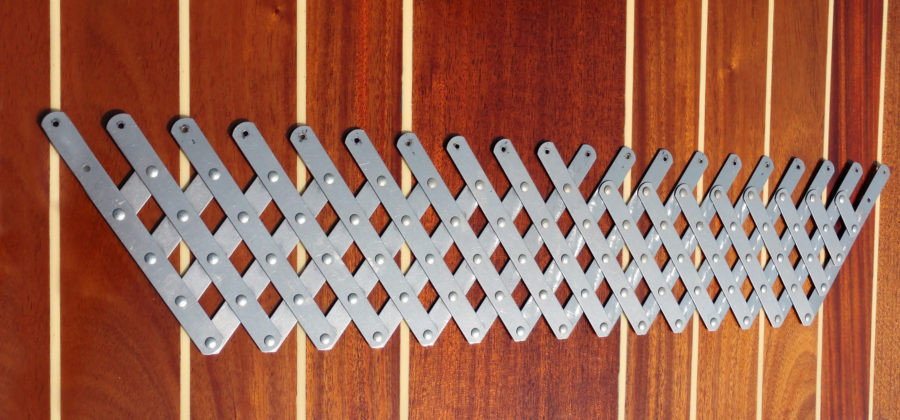

The grain of the board or plywood runs perpendicular to the boot. The bottom is reinforced with three hardwood cleats—two running the full length from front to back and beveled at the ends, and one in the middle running side to side. The middle cleat stops shy of the longer pair; the gaps make it easier to wash mud off that would otherwise get stuck at the intersections of the cleats. The H-pattern of the cleats help the pattens resist slipping in all directions.

The traditional method of tying a platten on makes a secure connection to a boot. Manila rope holds the knots well. See the video below to see how the line is tied.

The proper placement of the boot on the patten is with the toe sticking beyond the edge. This puts the ball of your foot close to its forward edge, and your heel near its middle. When walking on mud, you use a normal stride, putting your weight first on your heel, where it is distributed evenly across the patten. At the end of the stride, your weight transfers to the ball of your foot and the front edge of patten. That edge sinks while the back edge lifts, breaking the suction and prying the patten out of the mud.

That transfer of weight to the edge is what sets the mud patten apart from the splatcher. Splatchers extend beyond the toe of the boot, as well as the heel, so the weight remains within the perimeter of the splatcher. Since you can’t use the downward force of your weight to break the suction, you have to resort to lifting. That’s not only an ineffective way to break the suction, the upward force you apply with one foot adds to the downward force on the other foot. The more you struggle to release one splatcher, the more difficult you’re making it to release the other. That’s what I discovered with the improvised splatchers I had to cut myself out of. Trying to lift them only got me more deeply mired.

This 12″-square plywood patten has ash cleats, 3/4″ by 1″, set on edge and screwed to the base. The cleats on my 14″ pattens are a bit heavier—7/8″ by 1-1/4″. The 1/4″ gaps at the ends of the middle cleat let water sluice the mud out of the corners when it’s time to clean up. The stopper knots on the rope ends are Figure-8 knots.

The 1/2″ manila loops are set at a boot’s width and each loop, requiring about 2′ of line, is laced through holes drilled 6″ apart. The lacing line, coiled up here, is about 6′ of 1/4″ manila with a half hitch in each end to keep it from unravelling. The base is made of 1/2″ plywood, the same as I used for my 14″ pattens. My other 12″ pattens have a base of 3/4″ pine.

It takes me less than an hour and a few pieces of wood from my pile of scraps and cutoffs to make a pair of pattens. With them, mud doesn’t have to be a barrier to exploration. They’ve opened up a new landscape just as snowshoes do in snow.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly. He’s grateful to the Langstone & District Wildfowlers & Conservation Association for steering him away from splatchers.

A note about safety: If you encounter mud that is so soft that the pattens begin to sink, retreat to firmer ground. Larger pattens may work, but it’s possible that the mud is too soft to be traversed safely. Given my experience getting stuck with my jury-rigged splatchers, I’d advise carrying a knife and extra lacing lines.

Good for Flounder spearing as well. I haven’t tried mud patterns but splatchers you walk with a sliding motion, trying to lift a foot is impossible. Snowshoes use the same motion.

Hi Christopher,

I spent last weekend on my Drascombe Coaster up a creek on Hanford (Secret) Water and could have used a pair of splatchers/pattens.

As you probably know the Walton Backwaters were one of Arthur Ransome’s favorite places to visit on his yacht, NANCY BLACKETT. I’m a member of the Nancy Blackett Trust, which maintains and sails NANCY BLACKETT from her base on the Orwell River just up from Pin Mill.

All best wishes, excellent publication

Those pattens look like anchors and my boots can’t come off when tied into them. Looks like a death trap to me! Let’s try Turnagain Arm outside Anchorage when the tide’s out.

The mud pattens I made are modeled after those used in the bays around Portsmouth, England, where the tides have a maximum range of around 15’. Turnagain Arm has a maximum range of around 40’—second only to the Bay of Fundy—and a tidal differential over 27’ will create a tidal bore that will rush in over 6’ high at up to 15 miles per hour. The mud in Turnagain Arm is composed of glacial silt and the microscopic particles give the mud some peculiar properties that make it especially dangerous—it quickly softens when disturbed and when it resettles it becomes more compact. The conditions in Turnagain Arm may be extreme, but Charlie raises a good point: There are places where pattens cannot be used. If the mud is so soft that the patten sinks below the surface, you’ll get stuck.

We saw the belugas in Turnagain Arm a few years ago. Amazing:”Belugas are Back“

Years ago, I was working in a house located on a muddy bay. At lunch time, I noticed a pair of skies with running shoes attached to them, lying on the grass next to the beach. I asked about them and the lady of the house started laughing and said, “You should have been here. My husband—you can’t tell him a thing—thought that if a duck can do it, I can too.” He made the “skis” to retrieve wiffle golf balls from the mud flats at low tide. Apparently, after hitting a few balls, he put on the skis to retrieve them. It didn’t take him long to get stuck, and he called for help. His wife spent the next five minutes lying on the grass laughing, telling him “I told you so!”

Then she started cutting brush and started throwing it out to him so he could rescue himself, which he was able by crawling across the brush towards shore. She got in the last word, again, by hosing him off after he reached shore. And there lay the skis.

Twenty years later, I was planning a week-long sailing-canoe trip on Willapa bay, here in Washington State. It’s the second-largest estuary in the USA. Every low tide most of the bay is mud, and I had rigged the boat to live/sleep aboard. I bought a pair of Mudder Boots for around a $100. I didn’t need hip waders with these things. You can walk, or even run if you prefer, on top of the mud. (I’ll admit I’ve never tried running in mine.) The cost has gone up since—$144 now—still a bargain. This invention is better than sliced bread.

Looks like a worthwhile experiment for my clam-flat mud, ankle-deep stuff. Clammers use hip boots. I do shorts and wetsuit booties which go in over the top. But that is only a summer solution. I once tried it in Tevas and a sole was torn off.

Blue Hill Bay won. I made the 12″ pattens but the muck was too much for them as I immediately sunk in and never got more than a few feet from shore. Possibly larger pattens might work but, considering how oozy the mud is, I’m don’t think so.

As Charlie Matteson makes clear in his comment above, not all mud is equal. My initial trials, shown in the photos and video in my article, were in Duwamish River mud just south of Seattle. There the pattens worked beautifully. When I used my pattens on a midnight walk in the tide flats of the Snohomish River north of Everett (see my article Uncertain Ground) my pattens supported my weight well, but the mud was very sticky:

A few yards from the boat, the sand turned to mud and I couldn’t walk without having to pull my boots up behind me. I turned back, got my 14″-square pattens out of the cockpit, and tied them on. I clomped back across the sand to the mud and tried again to walk to the river channel. The mud was extremely sticky and the rope bindings tied tight over my boots pressed painfully across my instep. The mud stuck to the bottoms of the pattens, making them quite heavy; each step became increasingly difficult. Turning around without falling was a bit of a chore, and getting back across the mud I had just walked over was harder than it was the first time. I was relieved to get back to the sand.

The mud in Blue Hill Bay may be especially fine; you’re probably right that larger pattens might not help.

Blue Hill Bay is not exceptional on the Maine. Mud flats are or were clam flats with the clams living about 6″ down. Best investment to deal with clam-flat mud is to do what the clammers do: hip boots. This is halfway-up-your-ankle mud which can be negotiated nicely with wet-suit booties, but will destroy Tevas or other sport sandals. Good news with the mud is that I dropped one of those small pyramid anchors in it years ago with chain attached. The anchor is well out of reach now but I can check the chain, which is happily not rusting away buried as it is in an anaerobic environment.

I’m glad I found this page. My daughter has been stuck in river mud for 2 weeks. We made these pattens and, success, my daughter has her self esteem back. I know this article was written in 2017, but they work in 2019. Thanks!

I need to go out to see how far the ledge is below the top of the mud at low tide for a pile-diving project assessment. These may do the trick. Thanks.

Before you charge out, test the mud step by step to make sure the pattens are big enough to keep you at the surface and the mud is not too sticky.

Do any mud enthusiasts out there have any experience with the pluff mud in Southeast USA, more specifically Hilton Head Island? I would like like to make a pair and try them as the mud is quite soft and prone to many rescues. I avoided a call for a rescue after an hour of sitting down and pulling my boots off one at a time, rotating 180 degrees, taking a step and repeat. Not again without some pattens, if they have a chance.

Thanks