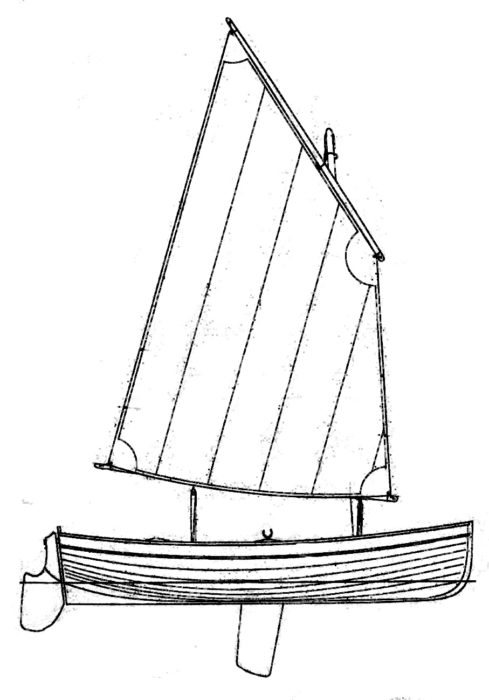

Iain Oughtred’s Guillemot is a multipurpose boat intended for rowing and for sailing with either a gunter or lug rig. He designed the boat 25 years ago and based it on the lines of a 19th-century ship’s boat or large yacht’s tender. It is intended to accommodate three adults comfortably, but could take as many as five over short distances in benign conditions.

Oughtred is best known for applying contemporary glued-lap plywood construction to traditional hull forms, and the Guillemot was primarily intended for that method. Glued-lap plywood has several advantages: it is easier to source the materials, easier to build, and results in a lighter boat. The Guillemot can also be cold-molded, strip-planked, or built in traditional lapstrake.

Regina Frei, a student at England’s Lyme Regis Boatbuilding Academy, opted for traditional lapstrake construction. Of the 319 sets of plans for the Guillemot sold to date, Oughtred believes that about 10 percent of the boats built have been traditional lapstrake, but suspects that percentage has increased in recent years. A glued-lap plywood hull is normally around 125 lbs; a traditional lapstrake one would be about 25–40 lbs heavier.

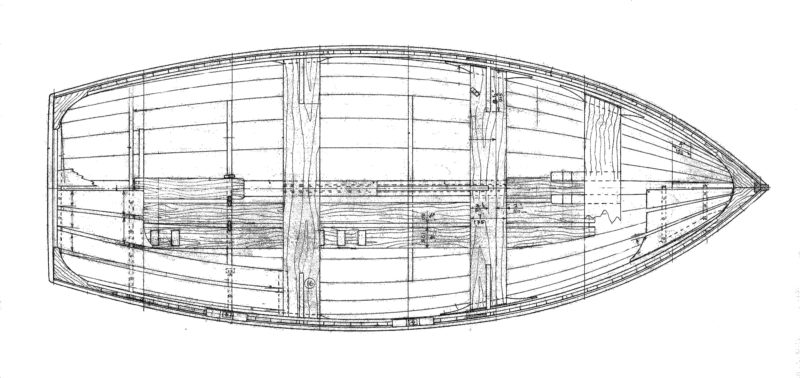

The plans include full-sized patterns for the stem, transom, floors, and temporary molds, and no lofting is required, but the Academy requires that students begin their projects with lofting, so Regina drew the lines from the offsets included with the plans, faired them, and created her own patterns. Oughtred’s drawings provide guidance for traditional construction, including scantlings for planking and steam-bent frames, frame spacing, and a recommendation for nine or ten strakes instead of the eight on the glued-plywood boats.

photographs by the author

photographs by the authorBuilding the Guillemot in a traditional manner provides lots of interesting and appealing details that are often absent in the glued-lap ply construction commonly used for Oughtred designed boats.

Aside from the applewood from her Swiss homeland that Regina used for the transom, she purchased sustainable materials and locally sourced timber as much as possible. The Douglas-fir for the spars came from the Stourhead estate less than 50 miles away from Lyme Regis, and the larch planking stock came from Scotland. (British boatbuilders generally agree that the farther north larch is grown, the better it is.) The ribs, thwarts, and stem were made of English chestnut, and the rest of the centerline structure, along with the inwales, outwales, and sheerstrake rubbing strips, were of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified oak. When an adhesive was required, she used a bio-based epoxy.

Oughtred’s plans for glued-ply construction specify that the hull should be built upside down, but he agrees with Regina’s decision to build her boat right-side up to allow easier access inside the hull for clenching nails or, as Regina chose to do, peening rivets. The assembled centerline was set up on a base structure, and seven temporary molds were then fitted on the keel hog and braced with supports going up to the workshop ceiling. Regina initially lined the hull for eight strakes, but this convinced her that she would be wise to follow Oughtred’s advice and fit a ninth strake. She then re-spiled accordingly, to more easily get the planks to follow the shape of the boat.

The Guillemot has two rowing stations, spaced about 3′ apart—close, but not impossible quarters, for rowing in tandem. Two stations come in handy for a single rower managing wind and passengers.

Regina had to steam the forward ends of the bottom three strakes and the aft ends of the top three so the 5/16″ larch planking could take the twist required by the shape in those areas. With planking complete, she removed the molds, fitted the centerboard case, and then steamed in the 1/2″ x 5/8″ English chestnut ribs and riveted them in place. The two thwarts followed, and instead of using the sawn knees indicated in the plans, she fitted a single steamed chestnut knee at each thwart end. Oughtred felt that single steam-bent knee might not be strong enough: “I would suggest that two each side should be adequate. Very neat, in fact; a lot more comfortable if sitting on the thwart, leaning against the gunwale, which you can’t really do, with the usual single knee.” Installing the seats in the bow and stern came next, followed by the oak outwales, inwales, and rubbing strips.

The whole boat was coated, inside and out, with a “boat soup” of tung oil, linseed oil, turpentine, and Stockholm tar, the last coat of which also had some Japan drier in it.

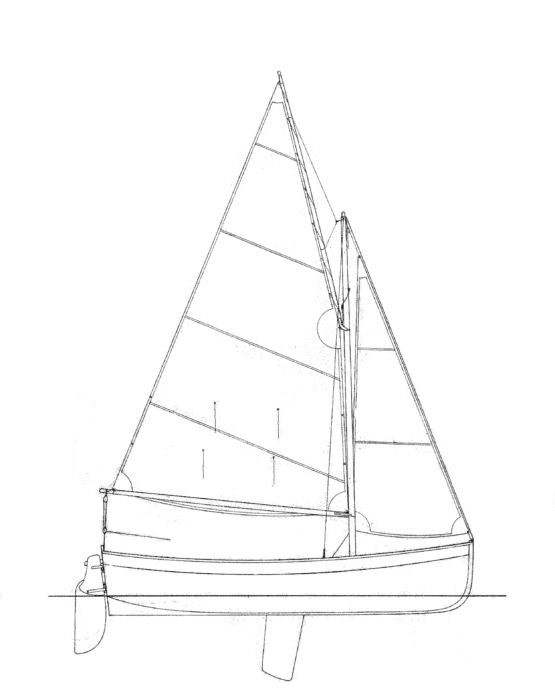

The sloop rig here carries 72 sq ft of sail. The plans include options for single sails: a balanced lug rig, with boom, carrying 64 sq ft of sail; and a standing lug, loose footed, carrying 55 sq ft.

Regina opted for the gunter rig with 72 sq ft of sail (the lug rig has 62 sq ft), “because it looks nicer and it will be more interesting to sail with a jib as well as a mainsail.” The mast is stepped on the keel hog immediately forward of the forward rowing thwart with no deck-level support. It has two shrouds anchored at the gunwale and a forestay connected to a bronze stemhead fitting that also takes the jib tack. The lug rig has an unstayed mast with partners spanning the gunwales at sheer height. Oughtred is considering adding something similar, perhaps at thwart height, to the plans for the gunter rig to allow easier stepping for the singlehander, although shrouds would still be required to brace the mast and provide support for the jib.

As soon as Regina’s Guillemot, christened LEAF, was launched, she rowed her out of the Lyme Regis harbor while her crew—Dan Adam-Azikri—prepared the rig. She rowed from the forward of the two rowing thwarts, and this would have been perfectly satisfactory but for the fact that the yard, boom, and sail were on the centerline ready to be hoisted, requiring Regina to row from an offset position. The centerboard and rudder blade were lowered, the sails that Regina made during a weeklong sailmaking course at the Academy were hoisted, and LEAF was underway. There was quite a chop in Lyme Bay for such a small boat, and only one other boat dared venture out of the harbor to sail. LEAF appeared to handle the conditions nicely, and I soon got the chance to see this up close after Regina and Dan rowed back into the harbor to fetch me.

The generous freeboard and firm bilges give the keep the Guillemot dry and steady in gusting winds.

Although there was some initial concern that the boat might be a little crowded with three of us aboard, the larger crew did give us an advantage in rowing and hoisting sails: Regina and Dan took an oar each in the aft rowing position and kept us head-to-wind while I sat comfortably in the bow seat and hoisted the sails from forward side of the mast. Dan and I then sat on the sternsheets benches either side of the tiller and took turns steering while Regina sat on the forward thwart and moved from side to side as we tacked to keep the boat level. We quickly got used to this arrangement agreed that it didn’t feel at all crowded. Had it been windier, we would have needed to get more of our weight to windward, but there would have been adequate space for us to do so.

The Guillemot’s performance was impressive. The gunter rig was easily managed, and we never seemed in danger of getting caught in irons when tacking. It was surprisingly easy to steer through the waves both upwind and downwind. The freeboard was just enough to give us a reasonably dry ride. While the wind was fairly constant, in the gusts that we did have, we didn’t have to react quickly to spill the wind from the mainsail or move our weight to the weather rail to keep the boat under us. It was clear that Oughtred had put an emphasis on safe, steady sailing so “you don’t have to hang out to keep her upright.” Still, the Guillemot was enjoyably lively. Oughtred later told me that he himself had been quite surprised at how lively the Guillemot was when he first sailed one.

The mast for the gunter sloop rig is supported by shrouds and a forestay, not a mast partner.

Regina–an experienced rower–later had a chance to row LEAF properly without having the mainsail and its spars in the way. She was by herself in the boat rowing from the forward thwart and was really pleased with the performance. Oughtred later told me that although that is the favorable position for a singlehander as the boat is currently configured, it would be better still to have single ’midships thwart aft of the opening in the top of the centerboard case where the rower’s weight would put the Guillemot in better fore-and-aft trim. He is thinking of adding this to the plans as an alternative to the two thwarts that LEAF has.

The Guillemot is a really nice and functional all-round sailing and rowing boat and it will take a small outboard, too. The boat is eminently suitable for two or three adults, or perhaps better still, a family of four with young children. It is especially pretty when built in the traditional manner.

![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Guillemot Particulars

[table]

Length/11′ 5″

Beam/4′ 5″

Weight/143 lbs

Sail area/lug, 62 sq ft; gunter sloop, 72 sq ft

[/table]

Plans for the Guillemot are available through the WoodenBoat Store and Oughtred Boats.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Beautiful woods, nicely done plank-on-frame.

Will the “boat-soup” finish eventually oxidize to black?

I am building a 14′ lapstrake dinghy using pieces of an old boat for patterns. Does anyone have a comment on my choice of clear 1/4″ Douglas fir for planking? I will be using copper clench nails for fastenings.