In the year when Finland celebrates its position as design capital of Europe, the issue of how to preserve tradition in the face of ever-challenging technology is as topical as ever. In a country once economically dependent on processing its “green gold,” woodcraft comes with mother’s milk. At the annual gathering of “traditional wooden rowing boats” in the eastern province of Savo every summer, the Sulkava rowing event attracts between 6,000 and 7,000 rowers, with three main categories of small boats, comprising several hundred craft.

Along with Finnish naval architect Terho Halme, a former Dutch marine engineer, Ruud van Veelen, is doing his level best to infuse modern design and construction techniques into these categories while still adhering to the less-than-precise rules of the competition. While basic dimensions such as the height of the sheer at the stem and stern are specified, builders also are obliged to maintain “traditional features,” such as raking the stem slightly and fitting oarlocks so that their pins do not extend over the gunwales.

The adoption of plywood in traditional boatbuilding predated the establishment of the Sulkava races, although originally even the 40′, multiple-oared “church boats” that have a long history in the region and were usually built from hand-sawn pine. The use of multilayered veneers for light weight has improved performance, and today finding any sawn-timber boat at a rowing gathering is rare indeed. Van Veelen has introduced non-local plywoods, such as okoume, which particularly challenged the race committee tasked with guarding “traditional style.” More particularly, he has pushed for the use of ultra-light construction, using epoxy resins and glued joints instead of tar, glue, and copper rivets.

Anthony Shaw

Anthony ShawRuud van Veelen, a marine engineer from Holland now living in Finland, was inspired by the popularity of rowing to develop epoxy-plywood boats of light weight and high performance.

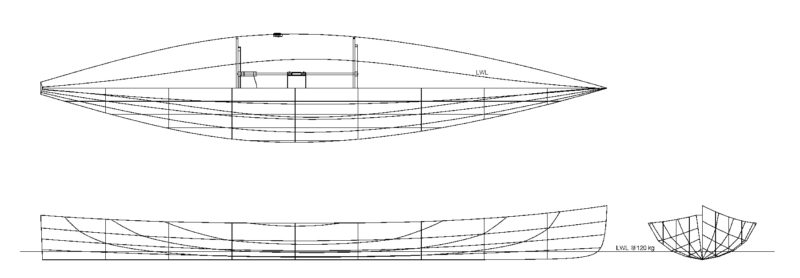

Hence the birth of the ultralight and fairly easily reproduced craft featured here, the Savo 650S rower. Living so near the venue of the Sulkava race, van Veelen had the demands of the local environment in mind: 60 kilometers of mainly sheltered inland waters where shallow draft and a long waterline are obvious advantages. His original design was a 21-footer that can be rigged for either single or double rowing, with the extra displacement adding only fractions of an inch to the depth of the load waterline. The Savo 650 is broader than his other design, the idiosyncratic “shift-rower,” in which one of the crew sits aft, wielding a long-handled paddle, and the two exchange places regularly to bring fresh energy to the sculls.

Apart from their sweeping chines, these two designs also share innovative hardware. Under the racing rules, the oarlock pin for the non-feathering oars cannot extend outside the line of the gunwale, but van Veelen developed a hinged pin that can be conveniently folded away during transportation. The sliding seat is of equally radical appearance when compared with traditional wheel-and-groove systems used on all other craft at the Sulkava gathering. Wheels are still required under the seat, but they have a pulley-like concave shape and run on top of two 7⁄8″-diameter stainless-steel tube rails running full length between beams attached to the two centermost frames. As well as looking very trim, the system is easy to adjust, since the footrests slide along the rails and are fixed in position by set-screws.

Anthony Shaw

Anthony ShawA simple sliding seat runs on stainless-steel tubes; the footrests are adjustable with set-screws.

Apart from the strictures of the race handbook, the Savo 650S is also very adaptable for non-competitive rowers. The longest major rowing event in Finland is actually the 200-km (124.3-mile) Karelia Marathon Row, held annually in the same lake as Sulkava at its northern extremity and finishing near the town of Joensuu. This also attracts a wide variety of craft and includes five overnight lakeside stops. Two of van Veelen’s customers use this design not only for the five-day event, but also for the 350-km (217.5-mile) round-trip there and back to Imatra, their home just 35 km (21.7 miles) from the Russian border. Although van Veelen is quick to insist that this design is not a cottage “runabout,” he points out that any rowing trip is easier when the craft has better hydrodynamic and steerage features, giving greater reward for energy expended.

My short outing in the four-strake version of the Savo 650S underscored these features. Given that most recreational rowing takes place under reasonably fair weather conditions, the disadvantages of light construction are somewhat relative. One keenly competitive customer even found that removing the 1.5-cm (0.6″) external “keel,” which runs along the whole length of the hull, did not radically affect the craft’s tracking characteristics, but reduced the wetted surface by 5 percent and saved an extra 1 kg, or about 2.2 lbs. Weighing less than 40 kg (88 lbs), the boat that I rowed got up to cruising speed very quickly, and even in a steady side wind held her course surprisingly well. She is less responsive to radical course changes, but with such low displacement can be maneuvered quite easily. My only surprise was the considerable overlap of the oar grips when in the resting position, about 30 cm (10″). This rowing overlap takes some getting used to, but this is actually a feature of all Sulkava racers, all of which are slender craft that do not use outriggers.

Anthony Shaw

Anthony ShawIn Finland, competitive rowing events are taken seriously. At Savo, the namesake of Ruud van Veelen’s design, races draw as many as 8,000 competitors, in a wide variety of pulling boats.

Construction of this model has so far been a professional task. “This is not a multiple-piece jigsaw puzzle to assemble, but it does require accurate initial cutting,” says van Veelen, who is so far the sole builder. He uses CNC, cutting from two-meter plywood sheets (6.6′) to precisely shape pieces that are then scarf-jointed to their full length after the initial cutting. Van Veelen also recommends the use of jigs for precise alignment, especially along the centerline. This enables creation of the simplest of lines without any chine battens and even without stitching, relying instead solely on epoxy gluing, using clamps every 10 cm, or about 4″. “Most home builders probably won’t have 120 clamps at their disposal, but there are ways around that, like temporary screwing and then filling,” he says.

Inspired by a comparatively small and light female customer, van Veelen has developed a slightly shorter version of his basic design. At 19′, this Savo 575 has proved quite maneuverable both on and off the water, yet it has retained good directional stability. She has proved that, like her forerunner, good handling qualities and minimum weight can be achieved by shrewd design and a construction technique that is simple but secure—and without using any fiberglass at all! ![]()

Contact Puuvenepiste in Finland for more information on the Savo 650. Old Wharf Dory in Wellfleet, MA, is an authorized builder of Puuvenepiste boats.

The Savo 650S is a lean and efficient machine designed for competitive rowing. Its construction is all modern, using lightweight plywood-epoxy techniques. However, its inspiration goes back to the Scandinavian “church boats,” so named because they were used for Sunday racing to and from church. In fact, one of designer Ruud van Veelen’s boats, similarly built, accommodates 14 oarsmen and a coxswain. Particulars: LOA 21’4″, Beam 4’2″, Draft 3″ (at a combined boat and crew weight of 265 lbs)

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.