In the last half of the 20th century, the southern New England coast and shores of Long Island were peppered with sturdy and simple workboats known as Brockway Skiffs. Designed and built by Earl Brockway of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, these budget-friendly plywood-and-lumber skiffs were ubiquitous in the region and used by professional watermen and recreational fishermen alike. Flat-bottomed and slab-sided, they were generally built in 14′, 16′, or 18′ lengths, and could be built as either skiffs or scows.

The boats developed a reputation for being able to carry a load, and they spread around the country and as far as Southeast Asia after the U.S. State Department adopted the Brockway design to aid typhoon-ravaged fishing communities. Built with less-expensive lumberyard-quality wood, roofing tar as adhesive, and galvanized nails, Brockways didn’t usually survive more than two decades, but they were easily replaced. With Earl Brockway’s passing in 1996, the boats’ numbers in the the southern New England coast dwindled, but his skiff still retains a strong cachet with backyard boatbuilders and designers alike, including Walter Baron whose refined Lumber Yard Skiff design has strong ancestral ties to the Brockway.

Photographs by Jason Pietrzak

Photographs by Jason PietrzakThe flat plywood bottom will pound in a chop. Placing the fuel tank forward minimizes the impact by keeping the bow down and minimizing the surface area presented to the waves.

Several years ago, I wanted to have a small, utilitarian, cheap outboard boat that was tied to New England tradition. I was on a strict budget but needed something stable and safe. A coworker showed me pictures of his Earl Brockway–built 14′ scow, and as I originally hail from the lower Connecticut River valley not far from Old Saybrook, the Brockway 14 was immediately a beguiling option. Timothy Visel, an educator and self-appointed Brockway historian, has developed plans for the Brockway 14 Skiff and posted them online. Visel took the lines off a conserved Brockway 14 in 2002. Much like the boat, the plans are straightforward and written with the novice boatbuilder in mind.

This type of boat construction allows the builder to get as fancy or simple as desired. The plywood can be A-C, marine fir, or marine plywood. Clear construction lumber is used for chines, frames, and gunwales. There is also a choice of adhesives and fastenings. I used meranti plywood, fir lumber, and a mix of PL Premium polyurethane construction adhesive for less critical joints and marine epoxy at the stem, chines, transom, and bottom joints. Sikaflex 291 would be another good choice in keeping with the spirit of a budget-built boat without compromising structural integrity. Depending on how long one wants the boat to survive, anything from galvanized nails to deck screws to stainless fastenings (as I chose) can be used. Traditional roofing tar can be employed to seal the joints, but superior modern glues, with only a marginal increase in cost, will improve the strength, watertightness, and life of the boat.

There are no difficult bevels or curves to be plotted during the construction. Straight lines are drawn directly onto two sheets of 1/2″ plywood for the sides, and the shape and rocker of the boat come naturally through the bending of the sides during construction. The start of the build is a fir 4×4 shaped into a stem with two dead-simple bevels. The two side panels, cut and joined with 1/2″-plywood butt straps, are attached to the stem and then bent around a single mold—made of 2×6s—that is temporarily placed amidships. The biggest struggle is attaching the sides of the boat to the 1-1/2″ thick transom, which is laminated from two 3/4″ plywood sheets. A Spanish windlass, explained in the plans, along with a second pair of hands perhaps, surmounts this obstacle.

The skiff is not designed to get on plane. The bottom is rockered from stem to stern rather than straight over the aft half of the hull as it would be for a planning boat.

Chine logs, made from 1×4 lumber, and floor timbers are installed next into the upside-down hull. The floor timbers butt and join the separate pieces of the bottom plywood, so no scarfing is necessary between bottom panels. A 2×4″ is specified as the floor timber, but I used some 4×4s I had on hand. Limber holes allow the water to drain the length of the boat. The 3/4″ plywood bottom is laid on the upside-down hull, fastened, glued, and trimmed. A keel for abrasion resistance is added along the centerline of the boat, usually made out of a 2×4 or 2×6, on the flat. I used an unfinished oak 2×4 and bonded it to the bottom with PL Premium and galvanized nails.

The boat is then turned over for fitting-out the interior. The 14′ version is light and well-mannered enough to be handled and turned over by one strong person with no special rigging necessary, while two people make this process supremely easy. Thwarts are then installed on 1×4 cleats, which tie the vessel together. Again, I used a mix of scrap 2×6s and okoume plywood that I had in my garage for the thwarts, but anything robust enough can be used, such as the stair tread that the plans recommend. The plans describe a center support post for each thwart, but I found the 2×6s to be plenty stiff and did not install posts. Flotation is strongly encouraged by Visel for safety. With the ample freeboard, there is room for high thwarts with stacks of foam underneath.

Because I built my Brockway with meranti marine plywood and epoxy, painted it with enamel Rust-Oleum, and keep it on a trailer, I decided against fiberglassing the exterior of the boat. One could certainly ’glass the boat, but it is not necessary and adds time ,expense, and weight to the project. It took me four weeks to build the boat from start to finish, working around my job. I spent approximately $600 on new materials and used leftover lumber and materials from past projects for the rest, and bought a used 6-hp two-stroke outboard for another $600. I estimate the Brockway 14 weighs somewhere around 350 lbs, and two people can carry the newly finished boat from shop to trailer. It’ll tow with ease behind any car and launching and retrieving it at the boat ramp are a breeze, taking just minutes.

The 4×4 post is not in the plans but the addition provides the skipper with something to hold on to while standing up. A tiller extension makes it possible to occupy a position close to the center of the boat and prevent the stern from squatting excessively.

When I first launched the 14, I was worried that it was going to be too tender—the bow seemed to me far too narrow. To my great pleasure, when I pushed it off the beach and jumped in over the stem, the boat barely knelt to acknowledge my presence. For a 14-footer, it has been rock solid and dependable from the first moments on the water.

The Brockway 14 is a straight-up workboat without any recreational pedigree. It is designed to carry fishermen and fish and whatever else needs hauling. It was not designed for high-speed running. Underway at displacement speeds, the Brockway 14 plows ahead, leaving a displacement-style wake that I take care to mitigate in anchorages and sensitive shoreline zones. When the speed increases, its shortfalls are easy to pick out. The easily drawn, long, straight plywood sides translate into an entire hull that is rockered. There is no flat run aft, as many such skiffs now have after design refinements, such as Baron’s Lumber Yard Skiff. Because of this, motor trim and weight distribution are crucial to keep the bow down as speed increases. If there is any sea while underway at speed, the boat will want to point to the sky as it stands on the rockered stern, and the bottom will start slamming. I have placed my fuel tank under the forward thwart to add weight in the bow. A passenger on the forward thwart with the skipper directly behind the center thwart offers the best balance for quiet handling characteristics.

When solo, I steer from a standing position just aft of the center thwart, using a tiller extension and a “chicken post”—an upright 4×4 that I use to steady myself while underway. The chicken post is a modification I made and is not reflected in the Visel plans. I can get the skiff going quite well from this position and, in calm water, can steer by shifting my weight.

Steering can be achieved by shifting weight to the inside of the turn.

Operated at sedate speeds in rough water, the workboat heritage comes to the fore and the Brockway offers a stable ride, shouldering the waves to the side and plunging forward with confidence. Slow isn’t a bad way to travel. While at full throttle, and with a person on the forward thwart, my skiff can achieve about 10 knots and leave a relatively quiet wake, but it’s hard on the motor to operate at red-line for long periods of time, and I usually cruise at a sedate 6 knots or half-throttle on my 6-hp two-stroke. We make excellent time over distance in a straight line compared to rowing and sailing, with the added pleasure of enjoying the sights along the way that are often missed at higher speeds.

With a 6-hp outboard, the Brockway can hit around 10 knots.

My wife and I spent three foggy days cruising some of the Maine Island Trail in our Brockway, TURKEY DINNER. With plenty of room for coolers and gear, the boat offered comfortable and economic cruising with all the extra amenities for beachside camping. We motored approximately 36 sea miles running at a leisurely 6 knots and consumed only 3.5 gallons of gas over the course of the trip. The skippers of lobsterboats waved as we passed, probably in recognition of the Brockway’s workboat sensibilities. The maximum rated horsepower for the boat is 25, but this would not necessarily lead to any speed benefits as the boat’s bottom was not designed to go high-speed running. I imagine a 9.9- or 12-hp motor would be an ideal intersection between speed and economy. The boat would ride relatively flat with a well-placed passenger up forward and would cruise at 10 knots without having to max out the throttle.

The Brockway 14 Skiff is not the prettiest boat I have owned nor the best performing, but it takes much hard handling and outdoor unprotected storage without complaint. Between the simple systems, steady feel, and absolute ease of use, I find it becoming my daily choice for fun, stress-less motorboating. The Brockway Skiff looks right at home in any shoreline waterway and is a practical option for an economical and approachable powerboat. ![]()

Christophe Matson lives in New Hampshire. At a very young age he disobeyed his father and rowed the neighbor’s Dyer Dhow across the Connecticut River to the strange new lands on the other side. Ever since he has been hooked on the idea that a small boat offers the most freedom. His previous Boat Profiles include the Atlantic 17 Dory and the TAAL SUP board.

Brockway Skiff Particulars

[table]

Length/14′

Beam/60.5″

Maximum Power/15-hp outboard

Passenger capacity/500 lbs

Passenger with cargo capacity/620 lbs

[/table]

The book How to Build the Brockway Skiff, by Timothy C. Visel, is available online from The Sound School, Regional Vocational Aquaculture Center, of New Haven Connecticut.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Very nice write up of an archetype, and lovely images, thank you. Simple to build and use, and capable beyond its unassuming appearance. What could be better?

As always, a great article from you, Christophe. What are you sailing these days? GIS to Sea Pearl to Caledonia Yawl to ?????

I am unbelievably boatless right now in terms of sailing cruising craft, but exciting things are on the horizon! Stay tuned!

Bought three boats from Earl, a new England yankee character from another age. In addition to a 12′ skiff for $150, i also bought a 9′ sailboat, including sails (Earl sewed them in cotton), for $140 and a 12′ sailboat including sails for $215 with surround seating. Earl didn’t like to make the larger sailboat, took too much time. I paid him in March to build it, he wouldn’t commit to a delivery time but he did complete it in mid June. He didn’t call, you just had to drop in periodically to check, but not too frequently.

Great memories,

Dick

I had at least five Brockway boats: 14′ scows, 16′ scows, a 16′ skiff, and a 20′ skiff.

Lobstered and gillnetted bunkers, mackerel in Guilford. (What happened to mackerel?)

Just turn boat over on beach for winter and paint bottom and launch in spring. What a time that was! Still have a miniature hull he sold me when I bought my last boat before he died.

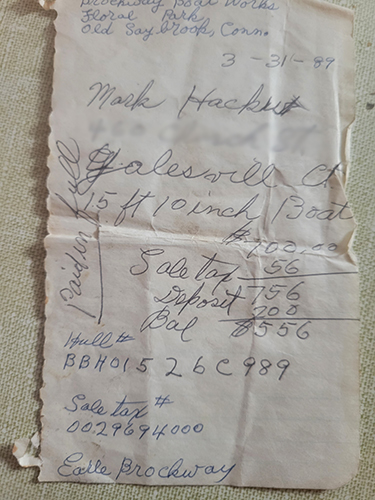

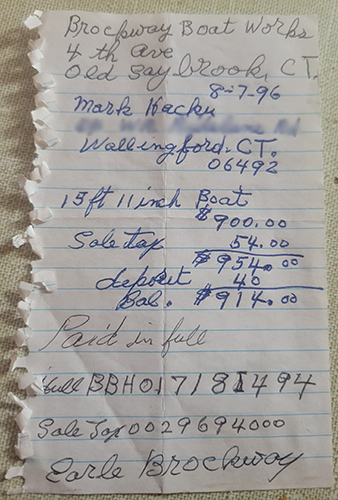

My buddy bought oars he made from ash or something that could row a skiff. I found these notepaper sales slips from Earl dated 1989 and 1996.

The DMV made him change to regular sales slip form soon after these boats. There was an increase in price, but he needed to put in more flotation, as well as customized seats, and widen the gunwale for balancing pots.

If you worked a boat, turned it over on the beach in winter uncovered, it would last 10 to 12 years. Material was just plywood so it would deteriorate. His way I guess to get return customers. He would deliver a caravan of small skiffs in tow across Long Island Sound to places that would buy and rent them at daily rates for bottom fishing. In Connecticut, customers must have just stopped and picked them up.

I’m sure he had other irons in the fire.

I’m 70 years old now, still fishing. I miss those boats you could bounce off rocks in the Thimbles blackfishing or duck hunting.

Mark Hacku

Grew up in Charlestown R.I., at the Shack on the way to the Breachway. Leon Grinnell was the last of his breed, I have no poetry to do him justice….a man’s man in every way, keeping his living from pond to sea teaching us all what we’d need to know. We dove off his docks daily and off his Brockway often…but I took pride the day he let me steer a line of eelpots in front of his seemingly ancient Johnson 18, and more so when I brought my son from Saybrook to Leon’s. Beginning of different wonderful days. Out in Arkansas, earlier today, I bought a deep green 14’×78″ scow , 15 horse Tohatsu/tiller…..just felt good being close to Leon and Earl among the best of men, from the best of times.

When I was a kid I had several friends that had the larger Brockway boat and we had a blast catching fish out of them. Many of them had British Seagull motors to power them as it was economical but took a while to get out to some of the fishing grounds. Very seaworthy boats in my opinion.

My Dad bought a bunch of Brockway skiffs in the early ’70s, towed them to Block Island from Saybrook and had a small rental fleet along with an 18′ Brockway scow as a garbage-boat business in New Harbor for a few years. I was too young to get involved at the time, but Dad took me to visit Mr. Brockway at his shop when I was in high school in early ’80s. I remember he had on an old pair of sneakers with holes and no socks. It was January with snow on the ground and he was working outside in his yard. There were 2X6s all over the place that he was coaxing to shape by bending them over barrels and other detritus in the yard with heavy weights tied to one end and the other jammed under something stable. That impressed me. I built my first skiff the following summer and will be teaching college students how to build a quick canoe (Michael Storer design) to use for hands-on wetlands conservation research next Fall. Like the other posters and countless others, Earl Brockway is a part of my story and history, and I cherish those memories and the simple, straightforward boats he created.