The Ellen 12 daysailer is a people magnet. At the ramps, people seem to come out of nowhere wanting to talk about it; in traffic they drive alongside and give a thumbs-up. Even out on the water, other boaters a quarter mile away will sail over just to take a closer look.

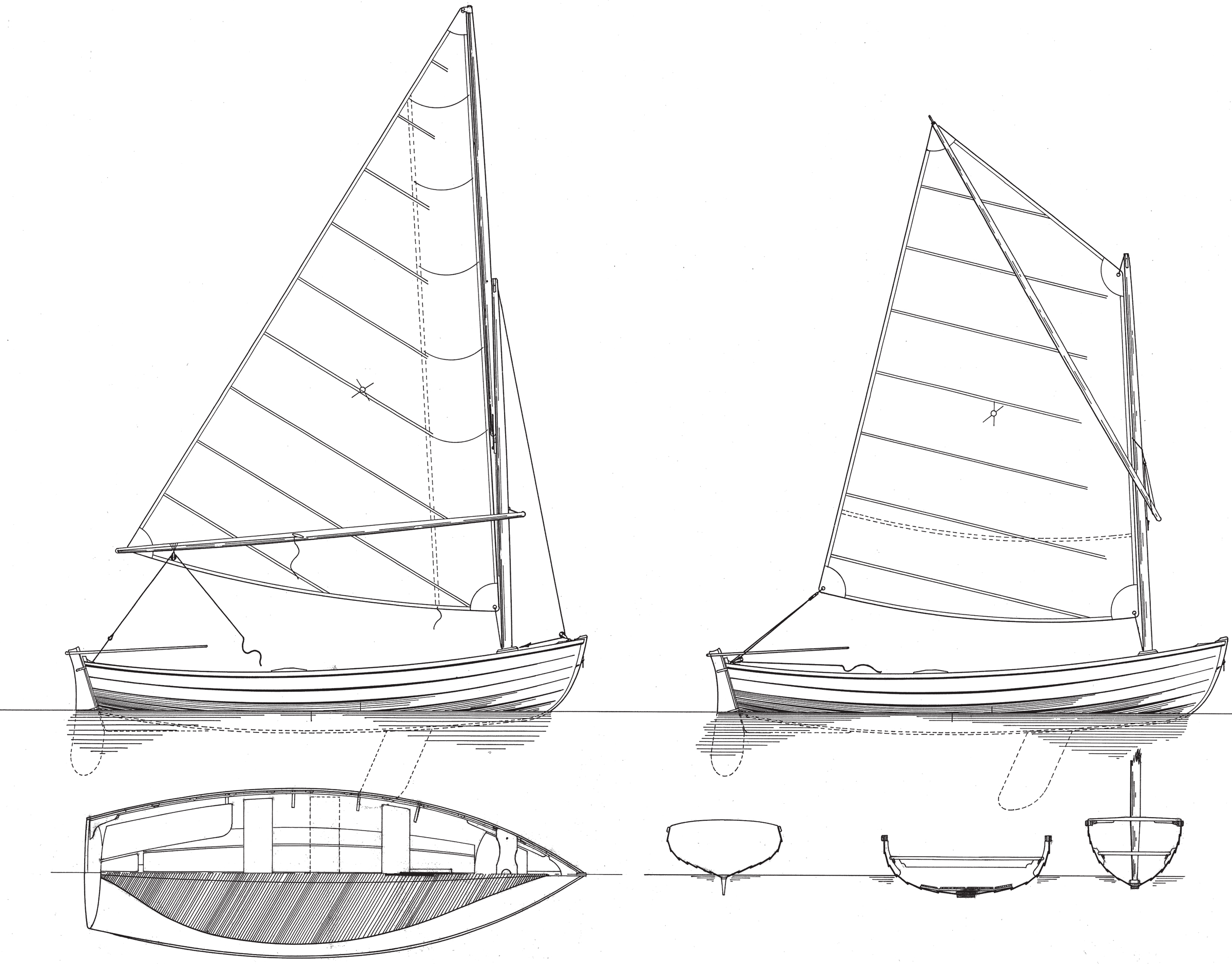

It is easy to see why. Designed by John Brooks in 1996, the Ellen sports classic lapstrake lines, a shapely transom, and a traditional spritsail rig. But the boat’s beauty is more than skin deep: it is a tidy performer that provides a confidence-inspiring, easily managed platform for joyful daysailing.

The Ellen is an attractive delight and seemingly the perfect small boat in many ways. Many amateur builders would jump right in if it weren’t for that one obstacle: lapstrake construction. It simply looks difficult, the kind of thing that separates the boatbuilder from the weekend carpenter. How does one gain the confidence to try it, particularly if one is learning the technique from a magazine article or book?

The plans for the Ellen from Brooks Boat Designs are on 12 sheets and include full-sized patterns for the molds, transom, rudder, and other parts. No lofting is required. The plans also cover the building jig that helps to simplify the epoxy-glued lapstrake construction. The book, How to Build Glued Lapstrake Wooden Boats, by John and his wife Ruth Ann Hill, is a 281-page compendium of information, referencing the complete construction of the Ellen in many examples. Detail is both the book’s greatest attribute and somewhat its obstacle. A reader can be daunted by the sheer level of detail and think the build is far too complex and will take too much time. That is really not the case. The authors simply care deeply about doing a high-quality job and showing you excellent techniques to get it right the first time. There is a lot to be learned from the book, but take it in doses. WoodenBoat magazine serialized the construction of the Ellen in issue Nos. 156, 157, and 158. Written by John and Ruth, the articles clearly present the proper construction sequence and contain some extremely helpful techniques.

Ed Neal

Ed NealThis model of the Ellen, built by the author, helped him become familiar with the construction processes before going to work at full-scale with expensive materials. The model includes three pairs of oarlock pads that are indicated by the plans.

To get comfortable with the process, I built a 24″ model of the Ellen using the construction drawing in the plans and following the magazine text. It was an excellent way for me to fully understand how the boat goes together and to learn skills such as how to spile a plank.

The Ellen is constructed from 6mm (1/4″) marine plywood planks. Okoume, meranti, or sapele BS 1088 plywood are all good choices. In both the articles and book, John details using a batten-guided circular saw for cutting out beautifully fair planks. The hull takes shape over a ladder frame that supports the stem, transom, and five molds. The forward three molds are mounted in a way that allows easy underside access to the lap joints for cleaning up epoxy squeezed from the laps before it cures. The plank laps are closed for gluing using a novel lap-clamping technique developed by the designer. Battens and drywall screws squeeze the laps tight, eliminating the need for mechanical clamps of any kind. Four pairs of sawn white-oak half frames set square to the planking add reinforcement to make a strong yet lightweight hull while being easier to fit than beveled frames set square to the centerline.

The plans present options for outfitting the interior depending on personal preference and intended use. The boat can be configured with a transom thwart and added sternsheets—“helm wings”—for sailing. It can be built with up to three thwarts to enable various seating arrangements for solo or tandem rowing. The thwarts can be made to be removable to open up space as needed for gear or sailing comfort.

Brian Hart

Brian HartWhile the plans are drawn with three rowing stations, the author opted to install just two and made the aft station’s thwart removable to open up the cockpit for sailing.

Since I would be sailing the boat with an occasional passenger and needed to row it off the beach, I opted for a transom seat and one thwart, the forward thwart reinforcing the top of the daggerboard case to be my rowing position. I added an additional set of oarlocks and built a second thwart I could quickly install for tandem rowing. This configuration provided an open, uncluttered arrangement.

Rowing off the beach meant stowing the 3′-long daggerboard and the fixed-blade rudder until reaching deeper water. When ready, the daggerboard slots easily into the case and holds itself well in the down position. The tiller fits snugly atop the rudderstock assisted by a pin, and the unit can be easily dropped onto the gudgeons without fighting the blade’s buoyancy.

The complete boat with rig comes in at around 135 lbs. I built the boat in two-hour increments, typically 8:30 to 10:30 p.m., often three nights a week, and logged 531 hours of construction time over 18 months. Being very light and matched to a lightweight aluminum trailer, the Ellen can be disconnected from the towing vehicle and hand-maneuvered to a launch site. Once at the water’s edge, one strong adult can lift and pivot the stern off the trailer and then lift the bow to get it onto the ground or into the water. This flexibility opens up many more launch site possibilities since no boat ramp is required.

Rigging takes five to ten minutes, longer if you have to attend to someone who has fallen prey to the Ellen’s magnetic charm and come up to talk. There are no mast stays. Simply insert the mast through the partner, mount the sprit, rig the sheet, brail up the sail, stow the daggerboard and rudder, ready the oars, and you are good to shove off.

The boat rows easily out to deeper water where the daggerboard is dropped and the rudder mounted. The brail line which binds the sail and sprit to the mast is released, and with the 60.5-sq-ft spritsail set and drawing, the Ellen quickly responds and comes up to speed. The rounded bilges provide reassuringly smooth stability and the fine entry parts the water for a comfortable, easy ride through chop. In gusts the Ellen easily communicates her changing positions without lurching and warns early of being blown overblown. Sitting on a cushion on the floorboards, one can easily see what is happening on the leeward side of the sail. There is no boom to clunk your head.

Rowing solo from the thwart at the daggerboard case puts the bow down and lifts the stern. With the skeg only skimming the water, the boat skews about a bit. With the addition of a passenger or ballast in the stern, the boat trims out and tracks well. My main interest in the Ellen is as a sailboat, and the unobstructed interior provided by the single daggerboard case rowing thwart makes it much easier for me to move about under sail. It is a trade-off with tracking ability I willingly take.

Brian Hart

Brian HartThe Ellen performs well under oars, but for those who require a motor, the stern is designed to support the weight of a small outboard and its operator.

With the fixed-blade rudder, sailing onto a beach is a bit sketchy but thrilling. One has to mentally calculate decreasing water depth and distance to the beach and quickly pull the rudder out of the gudgeons at the last instant for the final uncontrolled coasting onto the sand. On a brisk day, brailing the sail, pulling the rudder, and rowing in under control is the better option. The Brooks/Hill book has a drawing and instructions for making a rudder with a pivoting blade.

Windward performance with the spritsail rig is decent. This is a boat designed for leisure sailing, not racing. Because the Ellen is so light, you need to keep a vigilant eye on wind and weather conditions. If winds are in the upper teens, the Ellen will be overpowered and have difficulty making progress to windward or crossing the wind. You will have to frequently spill wind by easing the sheet to stay upright. If you are adventurous and a bit daring, you might devise a method to reef the sail while keeping the sprit in position to hold the peak aloft. It is something you will definitely want to practice first in light winds.

Brian Hart

Brian HartThe sprit rig, seen here, is designed with a single horizontal reef. The optional sliding gunter rig has a vertical reef, which can be employed without dropping the sail. Note the brail here crossing the sail from throat to leech.

Brian Hart

Brian HartWith the brail pulled home, the rig gathers neatly around the mast, clearing the cockpit for rowing when the wind fails.

Building my Ellen was the most satisfying thing I had ever done. Although it has been nearly 20 years since its launch, it continues to hold that record for building satisfaction. Like so many others, I continue to admire its good looks. A close friend seeing the boat for the first time said, “You know, in 50 years that boat will be in a men’s clothing store with dress shirts piled in it!” I can only hope.![]()

Ed Neal of Cleveland, Ohio, started his interest in woodworking as an eleven-year-old Boy Scout, whittling neckerchief slides. Twenty something years ago he came back from a wilderness canoeing trip in Canada wishing to add an outrigger to the canoe for additional safety. He went to the downtown Cleveland Public Library looking for a book that might be helpful. There he fell down the boatbuilding hole and has yet to surface. He is now the executive director of the Cleveland Amateur Boatbuilding and Boating Society.

Ellen 12 Particulars

[table]

Length/12′

Waterline/10′ 8″

Beam/48″

Depth, keel to sheer/18″

Sail area

Gunter/62.5 sq ft

Sprit/60.5 sq ft

[/table]

Plans for the Ellen are available from Brooks Boat Designs for $95. How to Build Glued-Lapstrake Wooden Boats is available from Brooks Boat Design and The WoodenBoat Store for $39.95.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Ellen 12 is truly a truely beautiful lapstrake daysailer. Awesome job, Ed!

John,

Did you make your soft boat fenders? If so, what rope did you buy to make your fenders? I’ve found instructions on how to make my own but I have not found definite advice on what roping to buy and where to buy it.

Paul Davoux

Hi John,

I bought the fender from The Knotted Line in Redmond, WA. They can make just about anything you need. They advertise in the classified-ad section of WoodenBoat. I’ve been happy with it and their service.

For the fender, traditionally, it would be manila, which is available through RW Rope in New Bedford, or cotton, which they also have. For longevity, you might consider their Hempex alternative. Or just give them a call—they know their rope!

I’d love to see this boat with a Duckworks Portage Pram Sail – albeit a bit small (until they offer larger fathead sail sizes). A simple high-performance sail rig would be smart on this beautiful hull – but I know it doesn’t follow form…