I began building reproductions of traditional Inuit kayaks in 1978 after the first kayak I’d built—to my own design—taught me how little I knew about kayaks. The Hooper Bay was the first of the reproductions I built to explore the technology of Arctic cultures whose survival depended upon kayaks; it was followed by several Greenland-style kayaks. The most sophisticated of the designs I built to was an Aleut baidarka collected in 1936 and housed in the Lowie Museum of Anthropology (now the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology) in Berkeley, California. I visited the museum and was given access to the collection storage area to see the unskinned frame. It was beautifully carved, and each piece of wood was finely textured with the marks of the edge tools that had produced it. The baidarka was undoubtedly the work of a highly skilled craftsman and I was sure there was much I could learn by reproducing it.

My baidarka clearly showed that the Lowie specimen had been very fast and had remarkable seakeeping abilities. It sparked my curiosity about Aleut kayaking equipment; I next made an Aleut paddle and bilge pump. I was also intrigued by the bentwood visors the Aleut hunters wore. Called chagudax̂, they were beautifully painted and often decorated with long, arching, walrus whiskers. To keep the whiskers from interfering with throwing a harpoon, they were usually set on only one side of the chagudax̂. The visors not only shielded a hunter’s face from sun and rain, they also put his eyes in shadow to conceal them from skittish prey. And by some accounts, the underside of the chagudax̂ made distant sounds more audible.

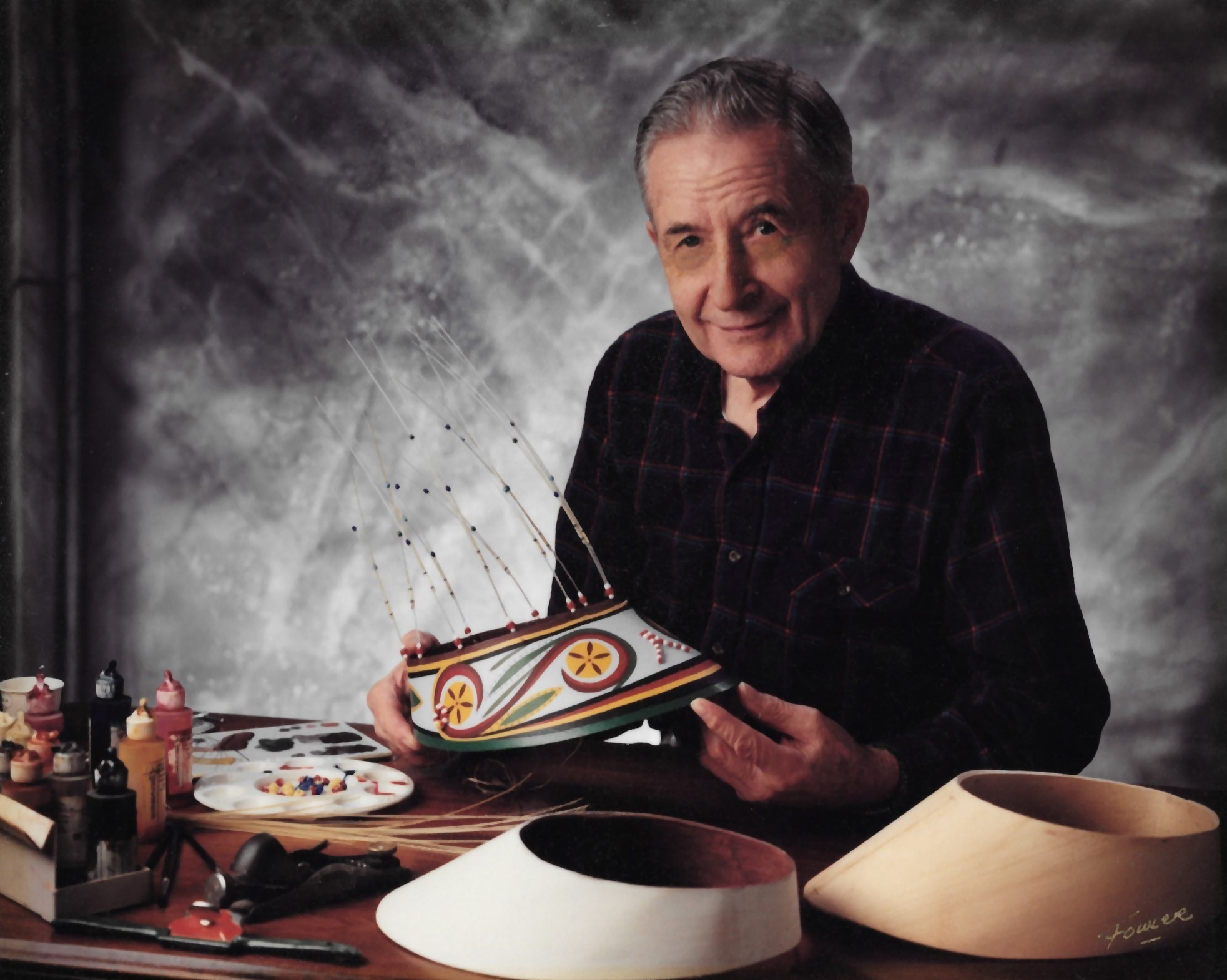

© Fowler Portraits

© Fowler PortraitsAndrew sat with some of his work for formal portraits that were used years later for a posthumously published book, Chagudax̂: A Small Window Into the Life of An Aleut Bentwood Hat Carver. It was co-edited by his daughter, Sharon, and published in 2012.

As I was researching the visors, I learned about Andrew Gronholdt. He was born in 1915, on Popof Island on the eastern end of the Aleutian Island chain. His father was a Dane and a boatbuilder, and his mother was Aleut, or Unangan, as the people of the islands refer to themselves. Andrew learned woodworking from his father and later in life put those skills to use working as a shipwright. His interest in his Unangan heritage led to study of the chagudax̂. Andrew became the recognized authority on the making of them, and classes he taught spawned a revival of the skills.

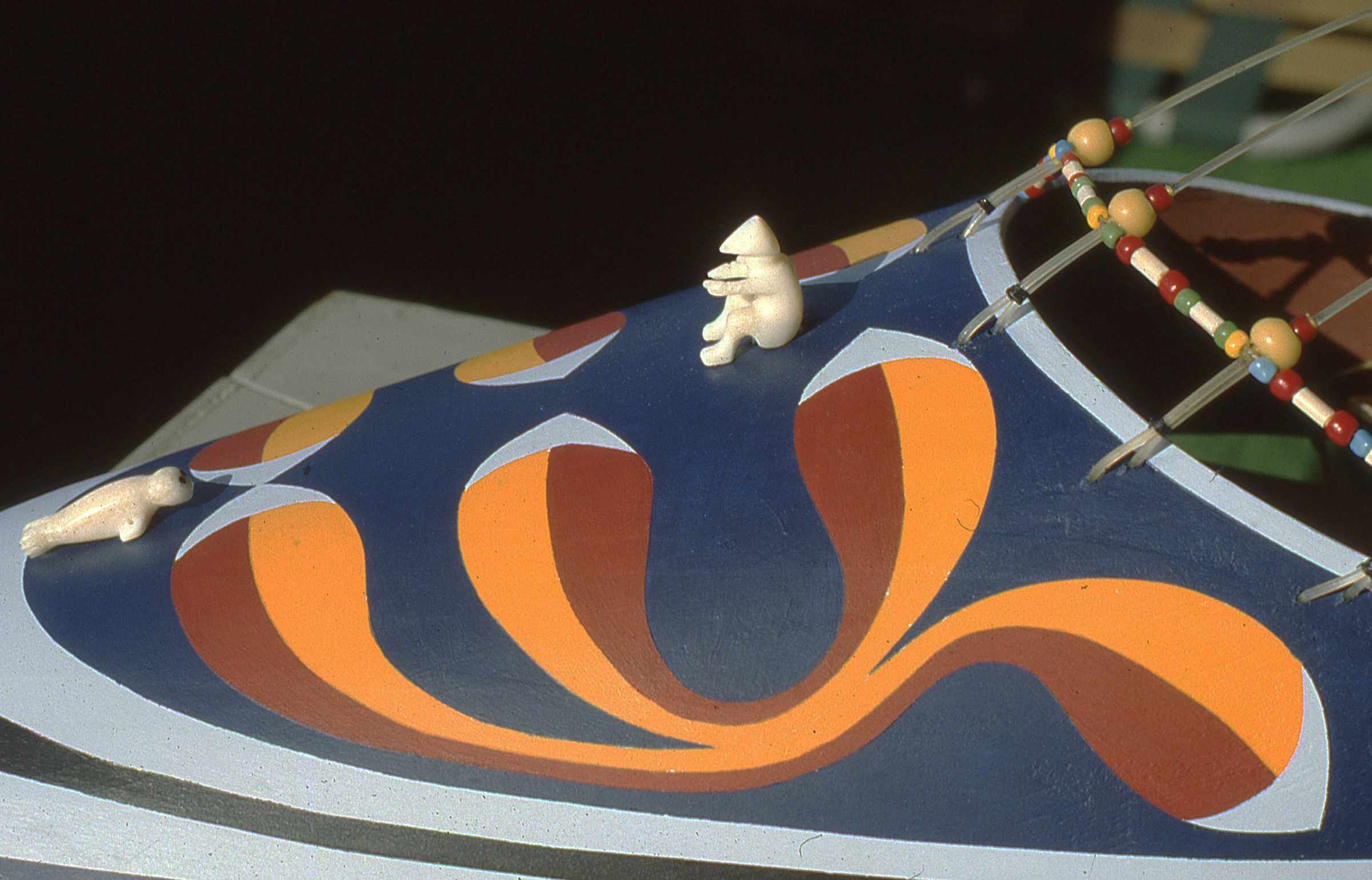

© Fowler Portraits

© Fowler PortraitsThe patterns painted by Andrew on this chagudax̂ are remarkably similar to those painted on a chagudax̂ collected in 1778 by an expedition to Unalaska Island led by Captain James Cook.

I was surprised to learn that Andrew lived in Edmonds, Washington, my hometown. I paid him a visit in 1993; he was 78 years old then, soft-spoken, cordial, and very willing to show me his work. He had both chagudax̂ in various stages of completion and a finished qayaatx̂ux̂, an even more elaborate type of headwear with a long bill and a conical shape with a closed crown. Several years later, when I was visiting the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural history in Washington, D.C., I saw that very qayaatx̂ux̂ on display in an exhibit of Aleut culture.

This photograph and those below by Christopher Cunningham

This photograph and those below by Christopher CunninghamA chagudax̂ like this with a long bill and well decorated would be worn by an experienced and successful hunter. I saw this chagudax̂ first at Andrew’s home, and a second time, years later, on exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution.

Andrew kept the decorative elements of his chagudax̂ true to historic examples, though they weren’t exact replicas of those preserved in museum collections. His long-billed visor here combined an ivory figure inspired by one chagudax̂ and painted patterns from another. Both of the originals are in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Leningrad.

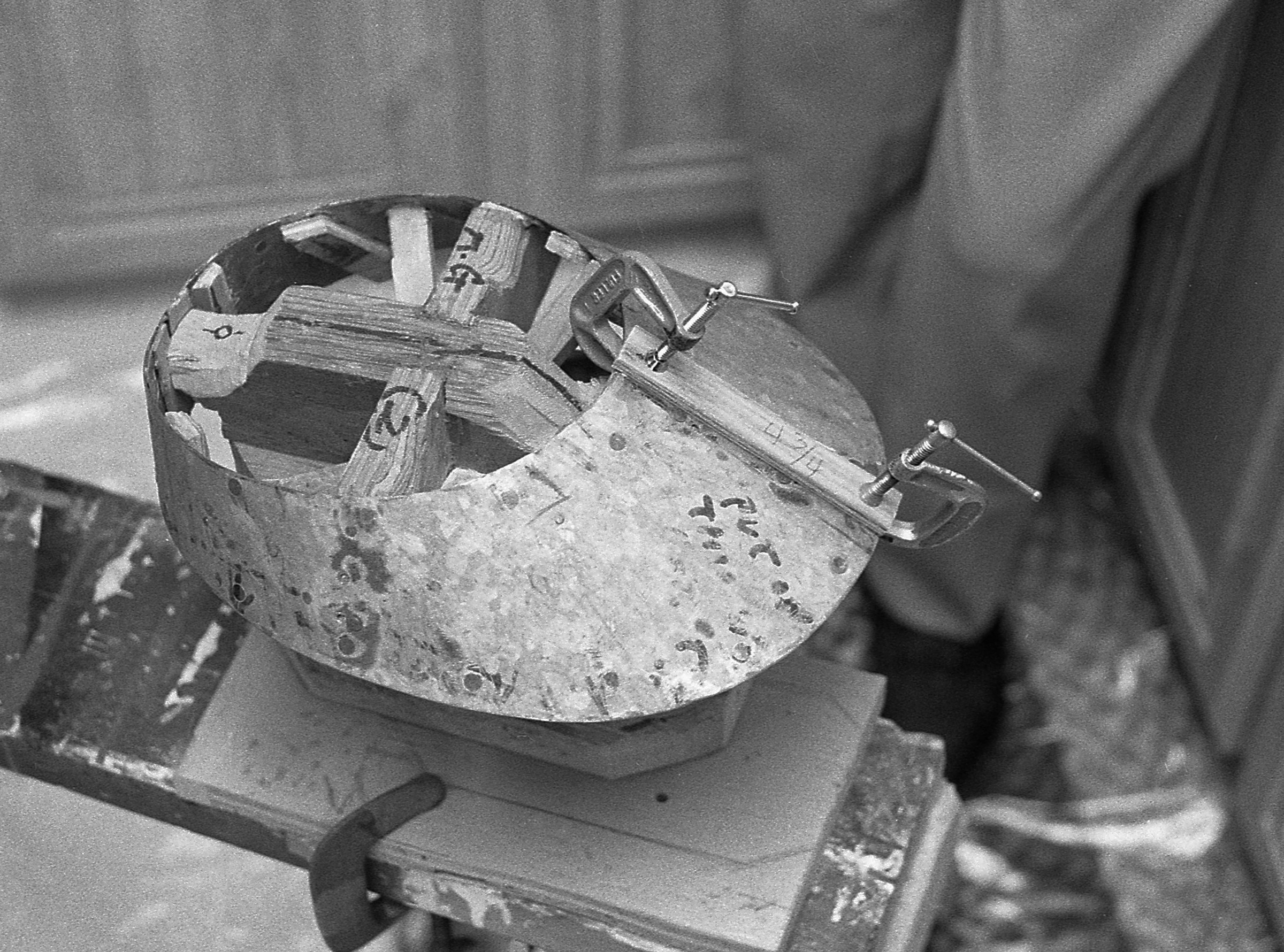

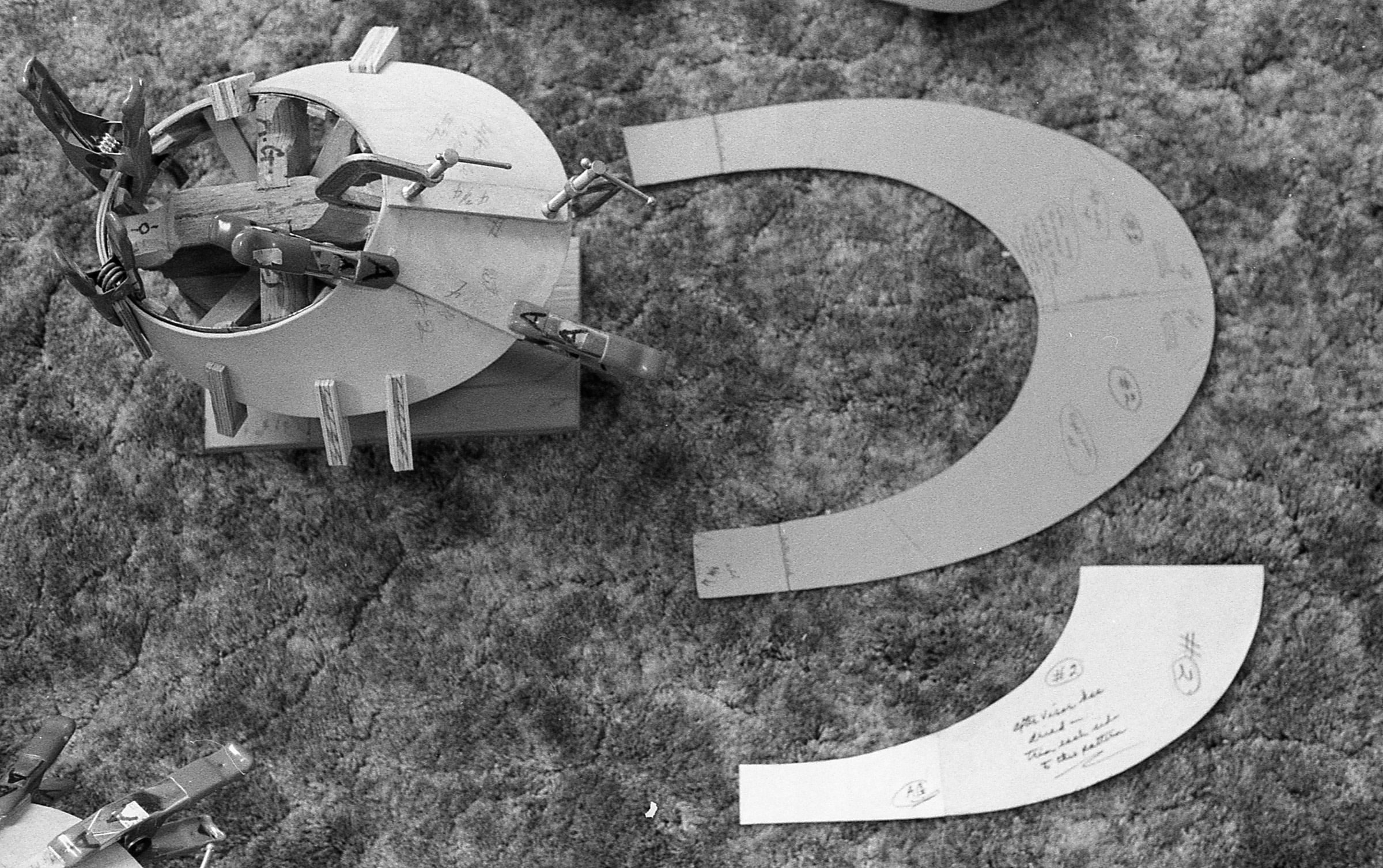

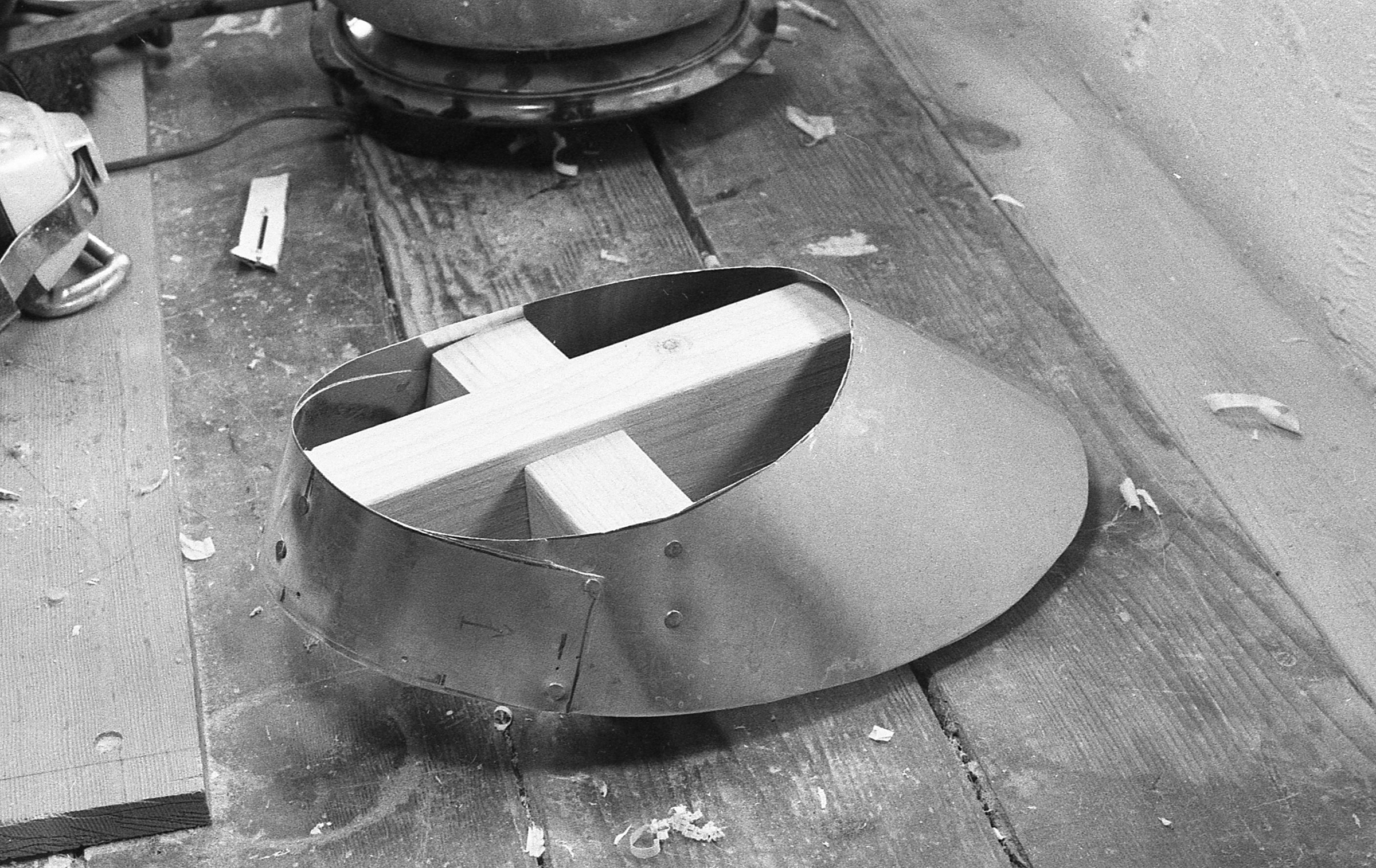

I was daunted by the complexity of carving required by the qayaatx̂ux̂ and focused on the simpler chagudax̂. Andrew let me trace several of his patterns and showed me how he bent the shaped wooden pieces over bending forms he’d made of galvanized sheet steel.

Andrew had bending forms for chagudax̂ of different shapes. He did the steam-bending in his kitchen with a plastic sheet on the floor to catch the inevitable drips. His legs, here in the corner of the kitchen cabinets, are the only photograph I have of him.

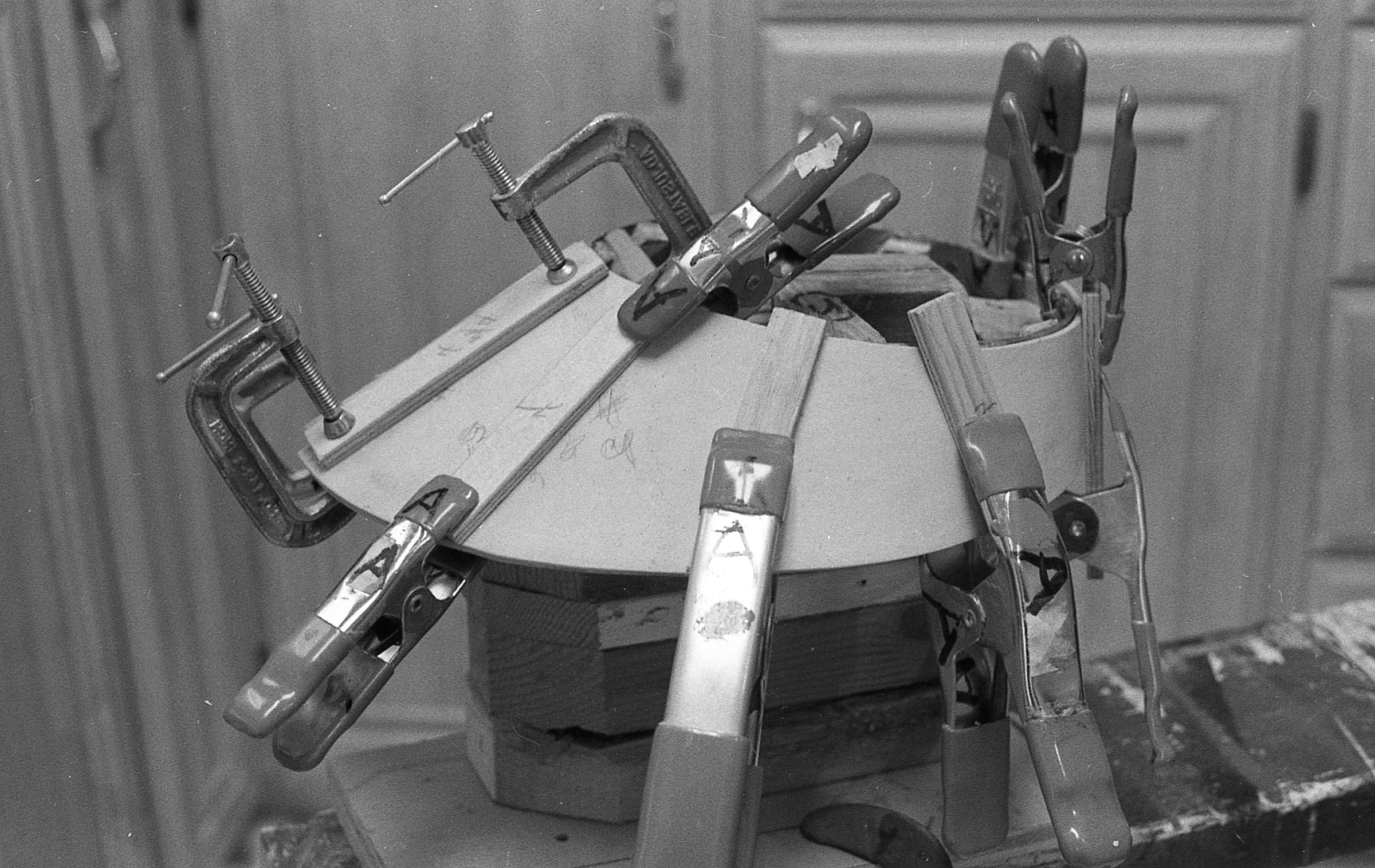

This bending form has steamed parts clamped to it. Two C-clamps hold a small caul over the half-lap joint; spring clamps and homemade clothespin clamps pinch the wood to the form while it cools. The full- and half-patterns are the ones associated with this particular form.

To retain its new shape, the freshly bent wood stays on the form while it cools and dries. After the wood has taken a set, the size of the chagudax̂ can be fine-tuned a bit by adjusting the overlap of the ends at the back.

He told me he made walrus whiskers from nylon weed-whacker monofilament. To straighten it, he would stretch wraps of it on a board with two nails in it and warm the monofilament with a heat gun. To taper a straightened length, he’d put one end in a drill and spin it while pinching it with sandpaper.

For making artificial walrus whiskers, I wrapped weed-whacker monofilament between two nails and took the curl out of it with a heat gun.

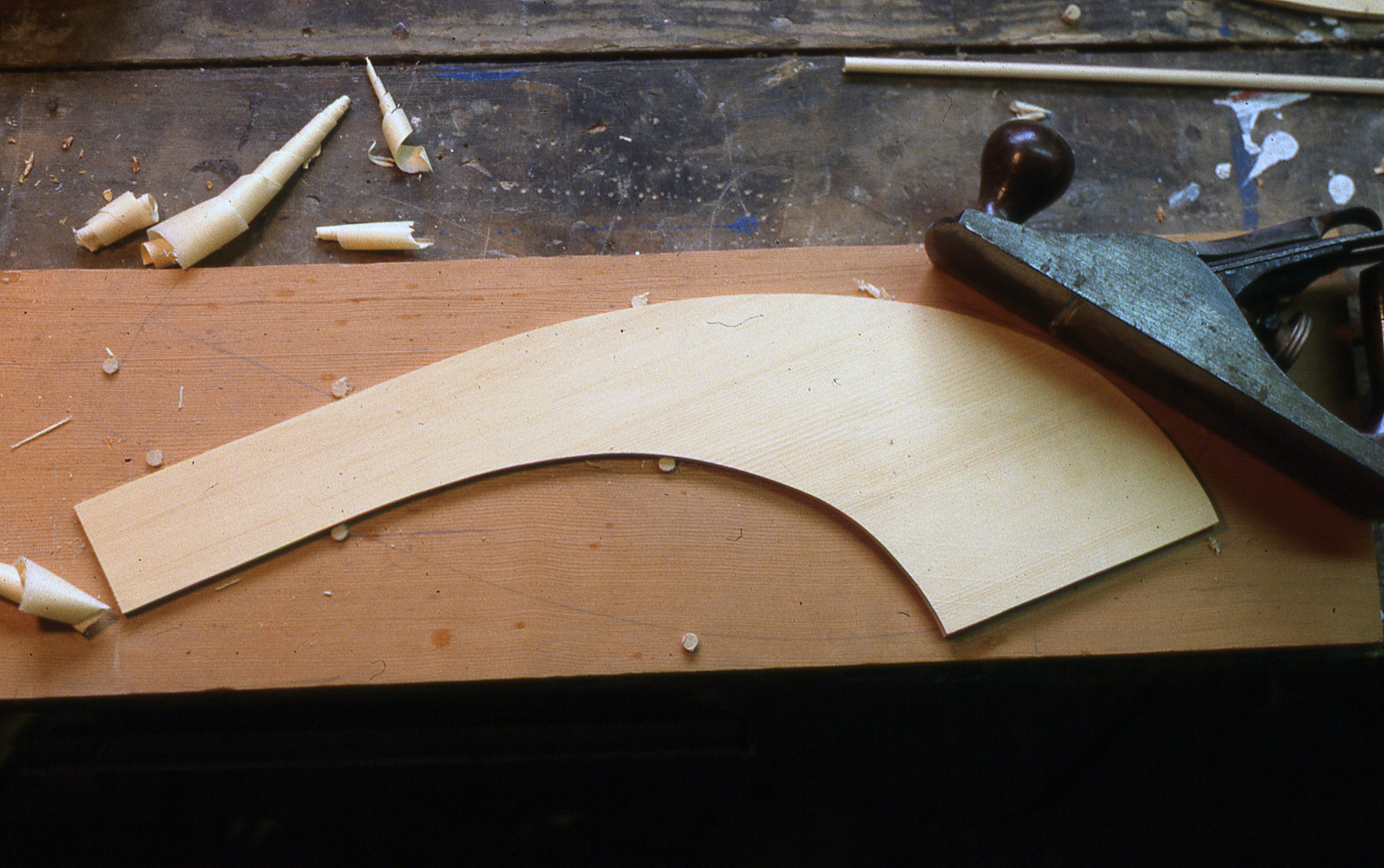

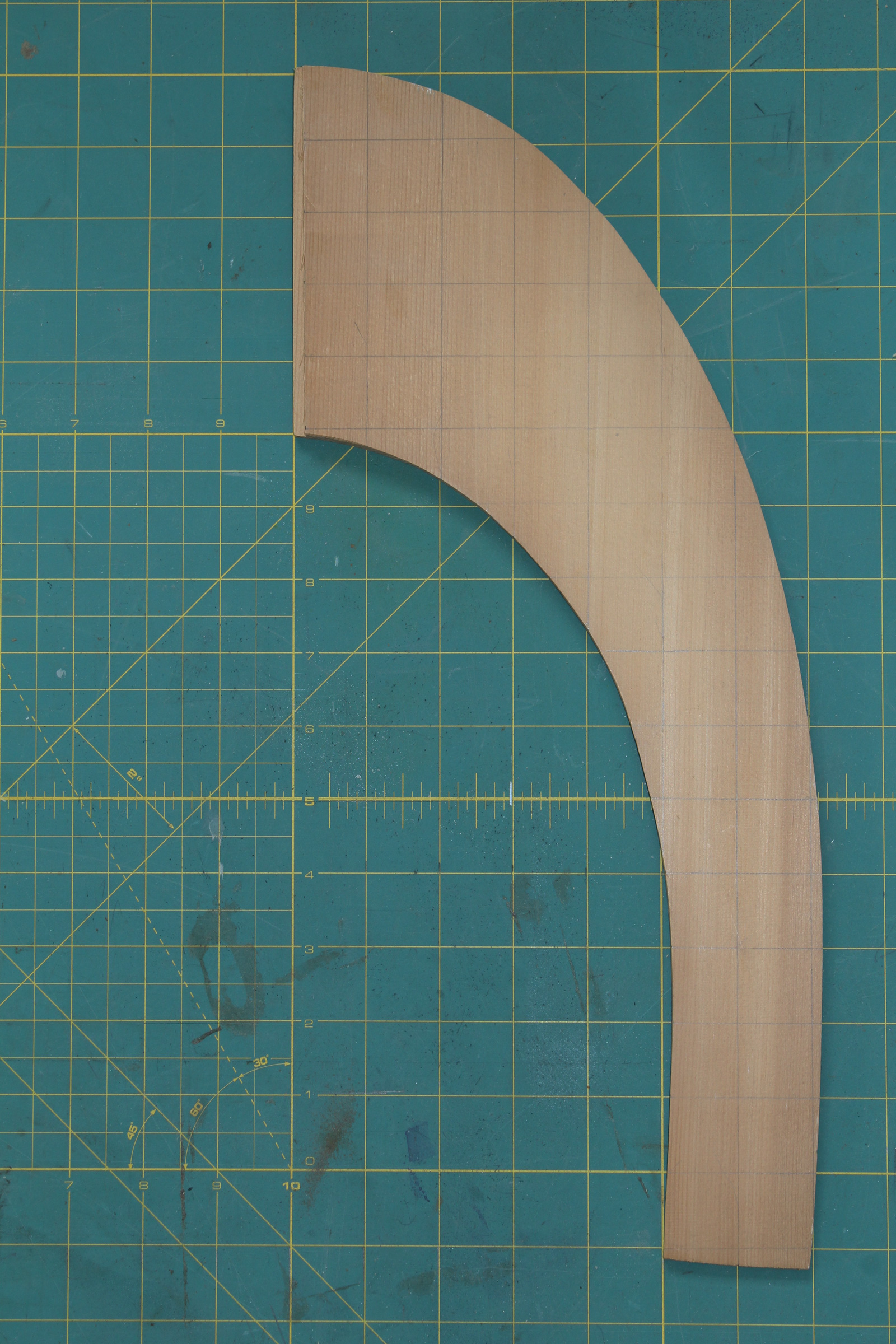

Using Andrew’s dimensions, I tapered each half of the chagudax̂ from a thickness of 1/4″ at the center of the bill to 1/8″ at the end of the arm at the back. A plank with dowels set at the outline of each piece held it in place for planing. I used vertical-grain Port Orford cedar, leftovers from planking for my Whitehall.

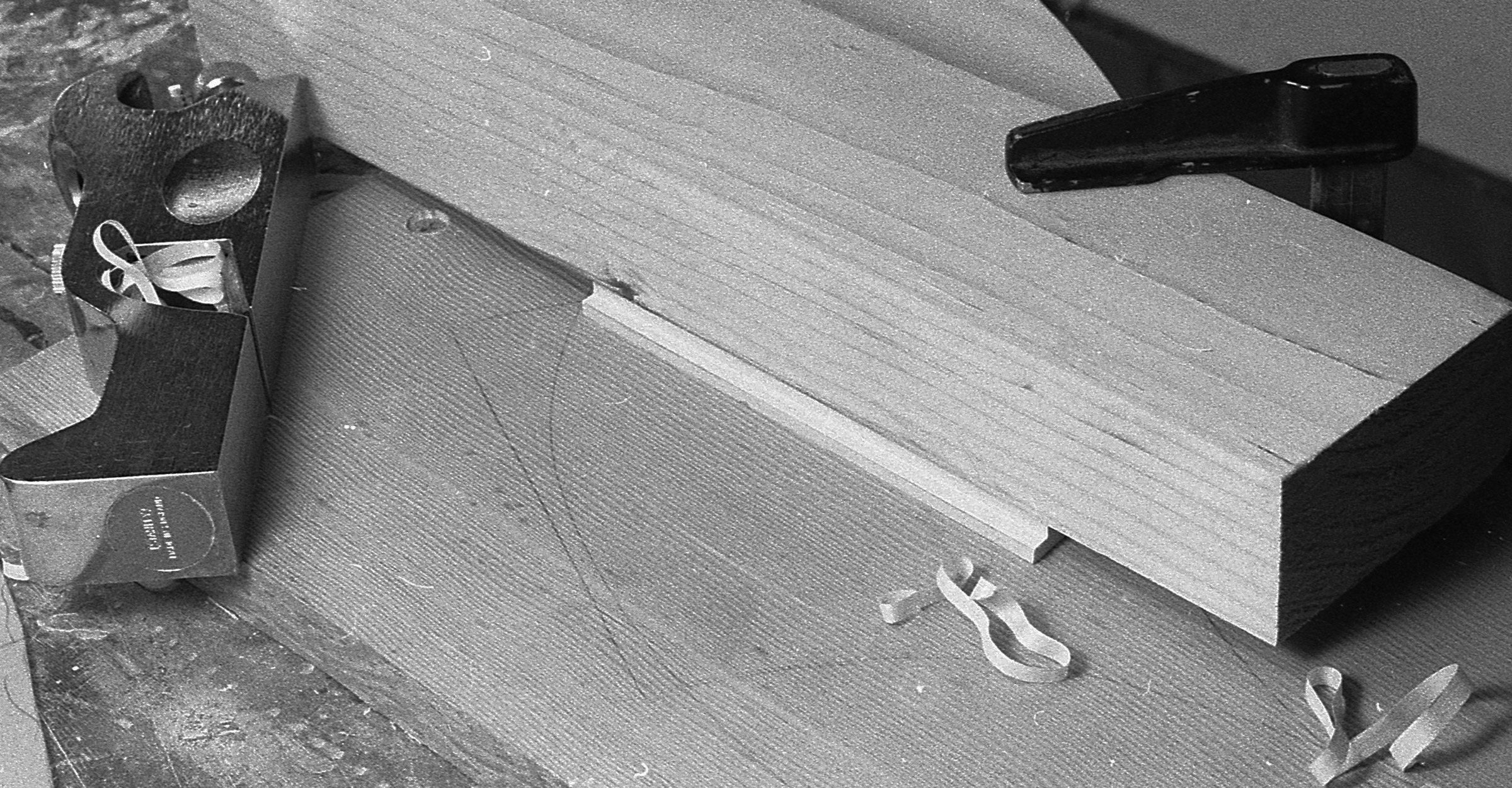

The two halves of a chagudax̂ are joined by a half-lap at the centerline. With a block of wood clamped on as a guide, a rabbet plane cuts the lap.

Like Andrew, I used galvanized flashing to make my forms. The zinc coating keeps the steel from staining the steamed wood that gets wrapped around it. With this form, I would soon find out one of Andrew’s refinements that I had missed: the ends of the wooden cross pieces need to be cut down to provide room for clamps.

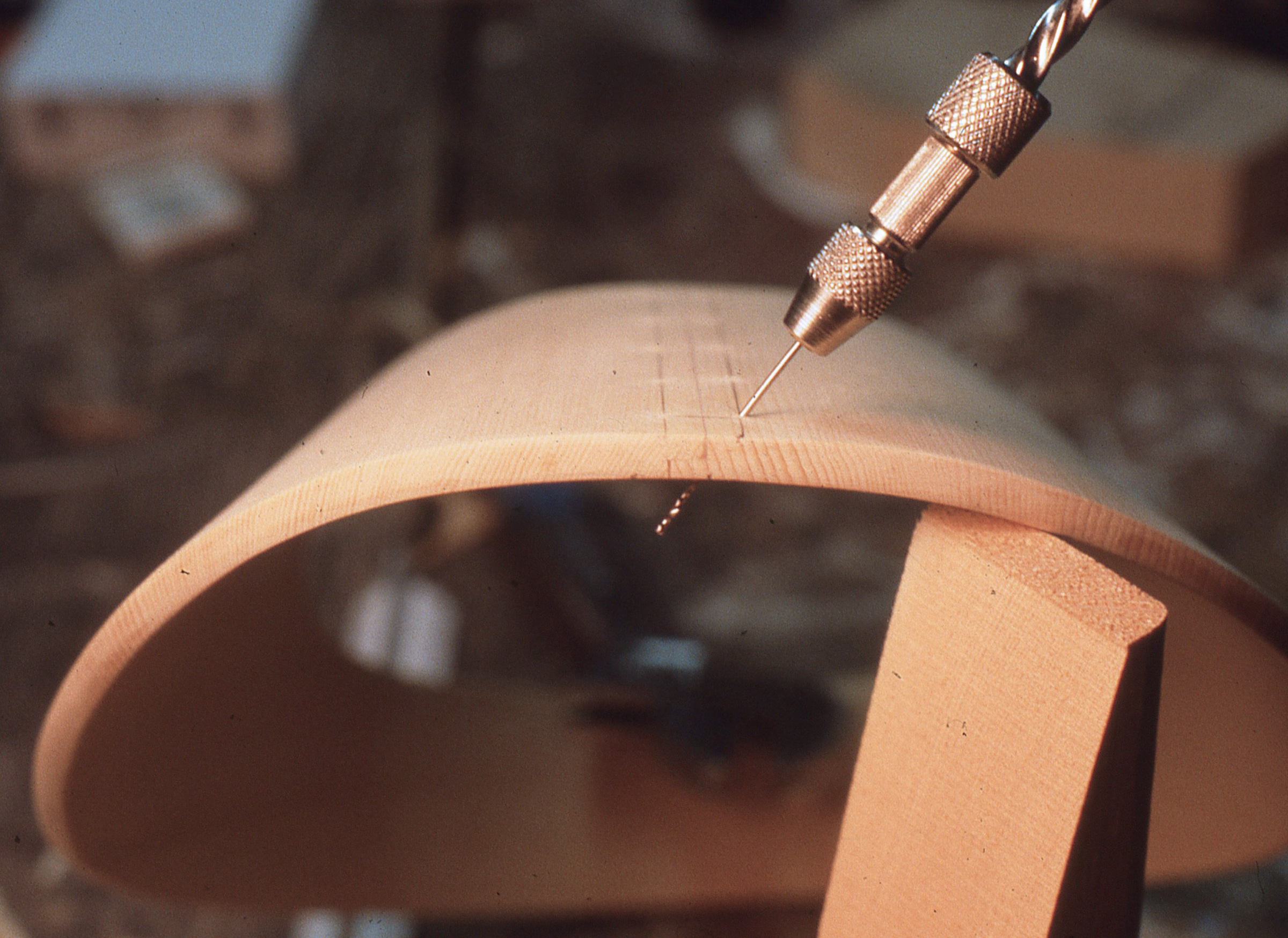

The holes for the lashing at the lapped joint are drilled at an angle to keep it centered over the seam both outside and inside. I glued the joints to make the lashing job easier.

After I finished painting my first chagudax̂, I started making a second.

While my chagudax̂ is a good match here for my Aleut baidarka, I’ve never risked wearing the visor while paddling it. As it is in the Unangan culture, the chagudax̂ is much more than a utilitarian object.

I was quite grateful for the time I spent with Andrew and went home equipped with what I needed to know to make my own chagudax̂. I made two, carefully painted both with Unangan-inspired designs, and adorned one with the faux whiskers. To give the glass beads used to decorate the whiskers a local touch, I made them by spinning molten glass on a bicycle spoke coated with kaolin as a parting agent. I collected glass from old debris uncovered by low spring tides: broken beer bottles for brown, a Noxzema jar for blue, and a Ponds Cold Cream for white.

I had put too much work into the two chagudax̂ that I’d made to risk damaging or losing them while boating, so I kept them as works of art and remained curious to know how they would work. I had been experimenting with PVC plastic cut from drain pipe to make megaphones and found that an 18″ section of 4″ drainpipe, cut down one side and heated for about 8 minutes in an oven at 170 degrees, would create a flat sheet 13-1/4″ wide—just a fraction of an inch shy of the tracing I’d made from Andrew’s patterns.

With my PVC visor, I heated the one-piece blank in the oven and molded it to my head for a perfect fit. The painted design is taken from the family crest brought from Scotland by my seventh great-grandfather.

After cutting the blank for the chagudax̂ from the sheet, I heated it again, a little less this time, and bent it into shape, let it cool, and then drilled and lashed the overlap. I painted the underside a dark brownish red, as Andrew did his hats. For the top, I didn’t adopt the Unangan patterns for my own, but used elements from my family’s private signal. After the paint was well cured, I custom-fit the visor by giving it a few minutes in the oven, then molding it on my head and letting it cool there. With contact along the entire perimeter, it has a comfortable fit, even where the bill’s edge makes contact with my forehead.

My PVC visor was quite plain by Unangan standards, but it proved to be eminently practical for cruising.

On my cruise at the end of last summer, I quickly grew to like the PVC chagudax̂. In bright, hot, sunlight it darkened the overhead glare in a much wider area than a baseball-style cap and protected the tops of my ears from sunburn. In a downpour, I wore it under my cagoule hood and was well shielded from the rain. And a chagudax̂, whether wood or PVC, doesn’t get soggy. It does indeed have an acoustic quality, though I noticed it mostly when I was motoring: when I looked down into the boat it made an almost startling amplification of the motor behind me. If the top of my head gets cold, I can wear a stretchy watch cap either over or under the chagudax̂. Thanks to Andrew, this versatile part of Unangan technology has found a place aboard my boat.

Andrew died in 1998 at the age of 82, and I regret that I had paid only one visit to him. There surely must have been more about Unangan culture and kayaking that he could have taught me. When I was doing more research at the time that I was getting ready to make my PVC chagudax̂, I read that he and Elisabeth, his wife of 65 years, had a daughter, Sharon. I searched the web for her and was ultimately able to connect with her through a Facebook page. I emailed her about my visit with her father and attached a photo of my chagudax̂, including the one I’d made from PVC drainpipe. I was a little worried about how she might react to taking Andrew’s inspiration away from the Unangan bentwood tradition and interpreting it in plastic. I was relieved when she replied: “You are a true Unangan! Our people made do with the materials available to them, right?” ![]()

The book, Chagudax̂: A Small Window Into the Life of An Aleut Bentwood Hat Carver, is available from Blurb, a self-publishing company.

Patterns

This half of a chagudax̂ is cut from a copy of one of Andrew Gronholdt’s patterns. The grid is made of 1″ squares.

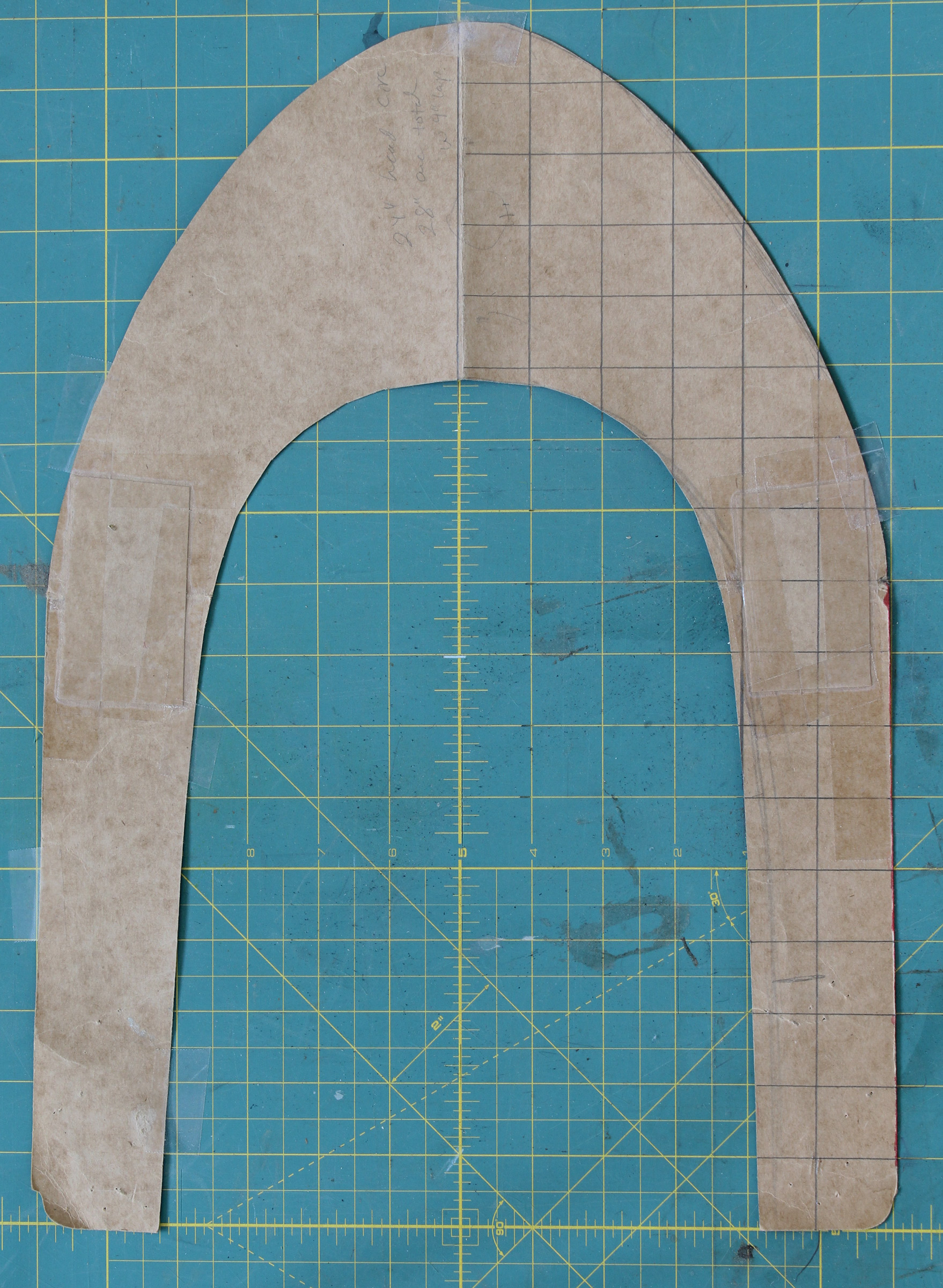

This is the pattern for my one-piece PVC visor. The fit created by a 4-3/4″ overlap of the ends matched my 7-3/4 hat size.

When my wife saw the pictures she told me some of her 4th grade students made replicas for living history class trips to Fort Ross on the Sonoma County CA coast. (The fort was founded by Russians who brought Aleut otter hunters down the west coast hunting for the fur trade with China.)

How does one pronounce Chagudax̂ and qayaatx̂ux̂?

I’d like to try making one. Or more. Could you take a picture of your pattern with something to show scale?

I’ve had limited experience with steam (and boiling water) bending wood. My impression is that, at least for hardwood, kiln-dried is less suitable than air-dried (sometimes completely unsuitable), so I’m wondering which woods are best and is kiln-dried OK?

At the end of the article I’ve added photos that you can use to make patterns.

I have no idea how the two Unagnan words are pronounced. There is an Aleut dictionary online with a guide to pronunciation, but I wasn’t able to figure it out. The Smithsonian Institution produced a nine-part series of videos on making chagudax̂, featuring two of Andrew’s students. Several people appearing in the videos have clothing printed with the word chagudux, but I didn’t hear the word spoken. On one web site, one of the people in the videos gave the Unangan word for sea otter as chagudax (with the plain “x”) and wrote that it was pronounced “chaa-kuu-the.” The Aleut dictionary had different words for sea otter, but I think it points out that the words aren’t pronounced as they appear to English speakers.

Andrew and the makers in the video mentioned above used Alaskan yellow cedar for making the hats and visors. I used Port Orford cedar for mine. Kiln drying tends to make woods brittle and less suitable for bending, but if it is all you have, soak the shaped pieces in water for a couple of days.

Thanks so much. The pattern’s a leg up on getting started. I figure I can make a pattern out of chipboard, try it out for fit and use that to make a form. Thanks again.

Here’s a link I found for Aleut pronunciation:

http://www.native-languages.org/aleut_guide.htm

Sort of to stray from the traditional approach, I wonder if cedar strip/bead and cove might be an option. Another option might be 1/8″ veneer plywood hollow-core door skins. I love the visor worn as part of a parka hood during foul weather.

The end of the article quote: “You are a true Unangan! Our people made do with the materials available to them, right?” Scrap used hollow core doors are available in my neck of the woods – making do with materials available to me…make me sort of a mid-American Unangan, too.

A great article, Chris.