When the now-defunct magazine The Boatman was launched in the early 1990s, one of its objectives was to provide boat plans suitable for amateur construction. One such boat was the Mallard, the first of which was launched in 1994. The magazine’s initial brief to designer Andrew Wolstenholme was to produce a modern version of SWALLOW, one of the boats in Arthur Ransome’s book, Swallows and Amazons. The brief called for a “boat-shaped boat which will genuinely sail” and with “considerable visual appeal to inspire the builder in the first place and along the way.” It should be big enough for two adults and small enough to be easily handled ashore and to be built in an average domestic garage—a length of 12′ would satisfy these requirements.

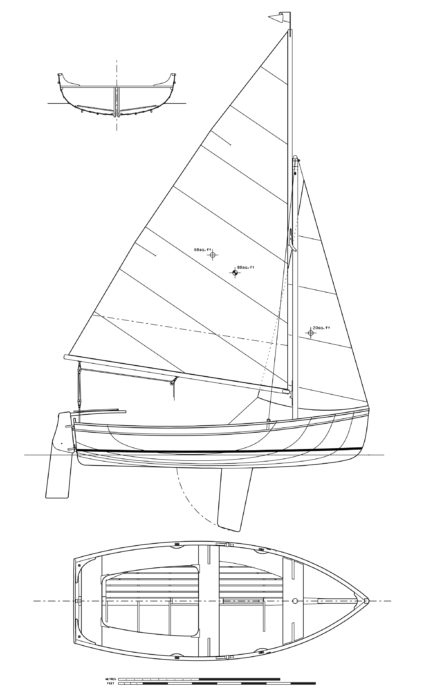

The SWALLOW described by Ransome in his popular works of fiction had a long, straight keel and no centerboard, but Andrew wanted to give the new design “a sailing performance that meets today’s expectations” while retaining “the aesthetic feel of SWALLOW.” So he based his Mallard’s hull shape on his earlier design, the 11′ Coot, giving it “a rockered keel to ensure good turning, an efficient airfoiled centerboard and rudder for good windward performance and maneuverability, and a skeg aft to ensure good tracking under oar.”

all photographs by the author

all photographs by the authorTim Harrison’s Mallard, newly christened TUCANA, was the only boat to brave the strong wind and rough water on Boatbuilding Academy launch day.

The Mallard was designed primarily for glued plywood construction—this satisfied the magazine’s aim to produce designs for the “more experienced, or more ambitious, builder”—but would also be suitable for cold-molding or strip-planking.

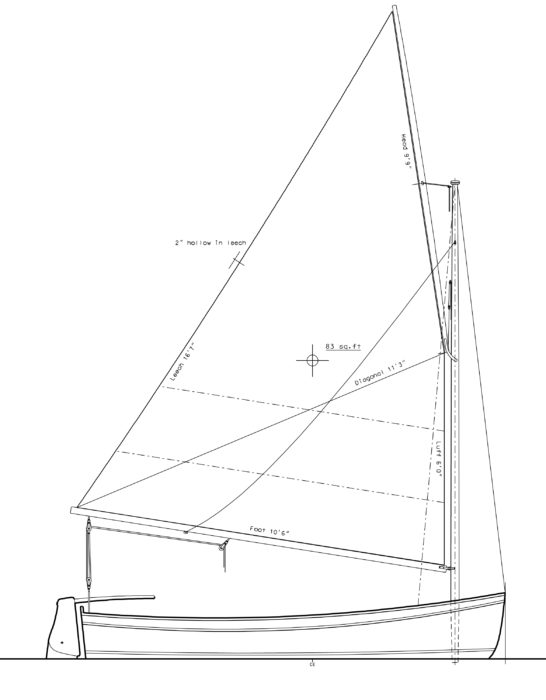

Although Jenny Bennett, the magazine’s editor, agreed with Andrew’s view that a gunter sloop rig would satisfy both the “sailing performance” and “traditional look” criteria, she also asked him to produce an alternative lugsail design. Ideally the mast for the lug version would have been unstayed and stepped through the forward thwart, but a further requirement was that the mast for both rigs be short enough to be stowed inside the boat when trailering. To do that without reducing the height of the sail plan, the mast was stepped on top of the forward thwart with shrouds to support it. This caused difficulties which Andrew foresaw and which the magazine’s own tester wrote about after sailing the prototype: “The problem is that the stays can interfere with the ability of the yard to swing well out or even forward of the mast when running.” A few years later Andrew had a specific request to design a cat rig for the Mallard (his Coot is also cat-rigged). The cat rig looked good and put the mast farther forward, opening up space in the cockpit for passengers. Adding mast partners at gunwale level close to the bow also allowed the forward rowing position to be used without unstepping the mast.

The mahogany gaff jaws were laminated to give strength to their curved shape. The gooseneck is an off-the-shelf fitting for a Mirror dinghy.

Tim Harrison is an ex-merchant seaman who also worked in the United Kingdom’s Hydrographic office, and when he retired he enrolled in the nine-month Boat Building, Maintenance, and Support course at the Boatbuilding Academy, Lyme Regis, U.K. He decided that while he was there he would build a boat that would be suitable to trailer all over southern England, and to sail with friends, his grown-up children, and his anticipated grandchildren—“real Swallows and Amazons stuff,” as he puts it—and the Mallard seemed to fit the bill. Having previously owned a glued lapstrake boat that he’d helped build, he decided that he would prefer “a smoother hull and a more modernish construction” and therefore would strip-plank his Mallard.

He ordered the plans from Andrew Wolstenholme, and although full-sized patterns were included, he lofted the boat in accordance with Academy course requirements. The package supplied by Andrew included CAD files, and Tim’s course tutors agreed, for convenience’s sake, that he could get the 10 molds CNC-cut by a local company rather than work them up from his lofting. The molds and the 7/8″-thick sapele transom were set up, upside down, on a structure raised to a comfortable working height. A solid sapele hog and a laminated khaya apron were fitted into recesses in the molds. Tim milled Western red cedar into 3/8″x 7/8″ strips and then started planking, a process he found to be relatively straightforward. He started at the sheer and worked toward the centerline, edge-gluing the strips with polyurethane glue and temporarily screwing them to the molds.

After cutting the centerboard slot through the planking and hog, he faired the outside of the hull and covered it with epoxy and 200gm (7-oz) fiberglass cloth. The hull was faired again after the epoxy cured. Tim then laid a 1/8” khaya veneer over the transom, and fitted the laminated khaya outer stem, the sapele 2 ¾″ x 7/8″ full-length keel, and a 1″-thick skeg. All but the top coat of two-part polyurethane paint was then applied before the hull was turned over to begin outfitting the interior structures.

After the inside was cleaned up, it was sealed with epoxy and 200gm cloth. The ¾″ plywood centerboard box was fitted, followed by the six ¾″-thick sapele floors to support the cockpit sole. The khaya gunwale cap was glued up with three sections: one inside the hull, one outside, and the third across the top. The top piece couldn’t be curved by edge-setting; it was cut to shape to match the plan view shape of the sheer. The completed cap gives the appearance of coming from one piece of 1 ¾″ x 1 1/8″ timber. Tim set a ¾″ x ½″ rubbing strake just below the sheer and painted the space between these two khaya strips red to give it the look of a sheerstrake above the white hull.

Originally, after some debate as to whether the Mallard should have side seats aft or whether people would prefer to sit or kneel on the floorboards to steer, Andrew included the seats in his drawings on the basis that individuals could always choose to leave them out. Tim opted to fit them along with the three thwarts, two of which would provide rowing positions, all in 7/8″-thick khaya.

Other khaya pieces included the hanging knees, lodging knees, and breasthook—all 1″ thick—and the centerboard trunk cap. Douglas-fir served for the floorboards and the mast; the boom and gaff are spruce. Tim made the sail himself—with the help of most of the other students—as part of the Academy’s five-day sailmaking course.

Finished with her first sea trials, TUCANA makes good speed on the return to the harbor.

As I drove into Lyme Regis on the morning of the Academy’s Launch Day I saw that, as forecast, there was a blustery breeze blowing from the east, straight into the harbor. I wondered how many of the seven new boats would venture out onto open water and if any of them would manage to sail. Tim’s Mallard, christened TUCANA, was the only boat to do both. Initially Tim and his crew Peter Holyoake, who also helped him throughout the build of the boat, rowed TUCANA out of the harbor and alongside a pontoon where they hoisted the sail. They then enjoyed a lively sail in the choppy waters of Lyme Bay. Tim is an accomplished dinghy sailor and he controlled the boat well, frequently planing downwind and occasionally spilling the sail going upwind. Not surprisingly TUCANA shipped some water, which Peter bailed out. Before launching, Tim told me that he might “scandalize” the sail to depower it when running back through the narrow harbor entrance, and I was slightly surprised to see that he did so by raising the boom with the topping lift. When he got ashore I suggested it might have been better to lower the outer end of the gaff and he agreed, but said that the peak and throat halyards were made off on the same cleat and he was worried that Peter might have inadvertently let everything go.

After a wet and wild maiden voyage, TUCANA brought her builder and crew safely back into the harbor.

Safely back in the harbor, Tim seemed to want to adopt a “quit while you’re ahead” strategy, but I persuaded him to have another sail with me, although we agreed that this time TUCANA would stay in the harbor. I took the tiller and immediately felt that she was exciting but controllable, although there was a bit of play in the rudder and tiller. (It would have been surprising if there were no teething problems and this was a very minor one.) It felt natural to sit on the side seats, and I am not sure if it would have been particularly comfortable kneeling on the bottom boards. Just as we started to tack, I noticed that the tiller had been mistakenly set above the mainsheet traveler rather than under it. Inevitably this meant that the rudder lifted off its pintles as we tacked through the wind, which resulted in a few moments of unwelcome excitement as I reached over the transom to replace it and get the tiller where it belonged. We were soon enjoying some more fun reaching in the harbor before returning to the shore.

While the builder mans the helm and the sheet, the crew keeps his weight aft and is ready to respond to gusts.

If I had been Tim, I’d have thought twice about sailing TUCANA in those conditions in Lyme Bay on her maiden voyage, especially when so many other sail-and-oar boats were staying inside the sheltered harbor and none were hoisting their sails, but the new Mallard met the challenge head-on and offered many pleasant surprises.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Mallard Particulars

[table]

Length/12′

Beam/5′

Draft, board up/6 ½″

Draft, board down/3′ 1″

Sail area/83 sq ft

[/table]

The cat rig

The gunter sloop rig

Plans for the Mallard are available for £110 (approximately $175) plus shipping. Jordan Boats will also develop kits for the Mallard subject to demand.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Awesome little boat well done. More build pictures would have been good too. Love the rig choices. I’m an unstayed Cat man myself.

There are build diaries on our Boat Building Academy website for all of the boats, including Tim’s Mallard, which is indeed awesome.

(On the Academy’s web site under Boats/Boat archive there is a lapstrake Mallard. On the home page there is a video about the Academy and the Mallard TUCANA appears briefly under sail at 0:56 to 1:00. Ed.)

Swallow and Amazon both had standing lug rigs, as do our San Francisco Pelicans. Amazon was a centerboarder, really more useful for a small boat, lighter weight for one thing. Swallow sank when holed.

When used with a yard downhaul as well as a boom downhaul, it is a very useful and tractable sail. We have a jib, set on a bowsprit (jib boom) which can be used if conditions warrant.