In 1831, one of Charles Darwin’s Cambridge University professors, John Henslow, had been invited to sail as a naturalist aboard the HMS BEAGLE for what was to be a two-year voyage to survey the coasts of South America. He declined the offer and recommended that Captain Robert Fitzroy take Darwin, his 22-year-old protégé, instead.

Darwin set sail aboard BEAGLE from Plymouth, England, in December 1831 and arrived in the waters of the Galápagos archipelago, after a three-year, eight-and-a-half-month voyage. On September 17, 1835, the ship’s crew went ashore on Chatham Island, the easternmost of the islands, now known as Isla San Cristobal. The young Darwin was not favorably impressed. In his book, The Voyage of the Beagle, he writes:

A broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is everywhere covered by stunted, sun-burnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life. The dry and parched surface, being heated by the noon-day sun, gave to the air a close and sultry feeling, like that from a stove: we fancied even that the bushes smelt unpleasantly. Although I diligently tried to collect as many plants as possible, I succeeded in getting very few; and such wretched-looking little weeds would have better become an arctic than an equatorial Flora.

I wasn’t feeling quite so peevish when I arrived at San Cristobal, by air, on May 16, 2005. The air was thick with heat, but the stands of Galápagos prickly pear, an endemic species first recorded by Darwin, graced the airport grounds and sleek sea lions dozed on the town-front beach. I had been invited by my friend Olaf Malver, founder of the guide service, Explorer’s Corner, to join a group of kayakers and journalists for a six-day tour of seven islands: San Cristóbal, Española, Floreana, Santa Fé, Santa Cruz, Santiago, and Bartolomé.

GALÁPAGOS VISION

Our 50′ catamaran mothership, GALÁPAGOS VISION, carried seven inflatable sit-on-top kayaks: three doubles and four singles. We would paddle a new island from her every day and every night the Ecuadorian crew would make the passage between islands while we slept.

Darwin had come to catalog the species of the islands’ flora and fauna and for that work he will be forever remembered. It’s baffling that as a naturalist he didn’t enjoy the experience more; the Galápagos archipelago is one of the more beautiful places on Earth. Below are some of the animals and plants that I saw along with my impressions and, for some of them, in italics, what Darwin wrote about them.

Galápagos marine iguana

Amblyrhynchus cristatus (Galapagos marine iguana)

Darwin wrote of the Galápagos marine iguana:

It is extremely common on all the islands throughout the group, and lives exclusively on the rocky sea-beaches, being never found, at least I never saw one, even ten yards in-shore. It is a hideous-looking creature, of a dirty black color, stupid, and sluggish in its movements. A seaman on board sank one, with a heavy weight attached to it, thinking thus to kill it directly; but when, an hour afterwards, he drew up the line, it was quite active. Their limbs and strong claws are admirably adapted for crawling over the rugged and fissured masses of lava, which everywhere form the coast. In such situations, a group of six or seven of these hideous reptiles may oftentimes be seen on the black rocks, a few feet above the surf, basking in the sun with outstretched legs.

I threw one several times as far as I could, into a deep pool left by the retiring tide; but it invariably returned in a direct line to the spot where I stood. I several times caught this same lizard and as often as I threw it in, it returned in the manner above described.

Darwin chalked up this repeated return of the iguana to a “singular piece of apparent stupidity,” missing the fact that the iguana always knew exactly how to find its way back to where it belonged. I found the rocky shores were teeming with marine iguanas. The tops of their heads looked as if they had been crowned with barnacles, and their skin of scales hung in loose folds like chain mail. Despite their formidable appearance, the one above, with its enigmatic Mona Lisa smile and drowsy half-closed eyes, conveyed how gentle they are.

Galápagos land iguana

Conolophus subcristatus (Galápagos land iguana)

Like their brothers the sea-kind, they are ugly animals, of a yellowish orange beneath, and of a brownish red colour above: from their low facial angle they have a singularly stupid appearance. They are, perhaps, of a rather less size than the marine species; but several of them weighed between ten and fifteen pounds. In their movements they are lazy and half torpid.

I watched one for a long time, then walked up and pulled it by the tail, at this it was greatly astonished, and soon shuffled up to see what was the matter; and then stared me in the face, as much as to say, “What made you pull my tail?”

At the west end of Isla Española, we went ashore and followed a rough boulder-paved trail. I walked with my head down, picking my steps as much to find sure footing as to keep from inadvertently stepping on the iguanas that were draped over the rocks and nestled in the crevices between them.

Galápagos giant tortoise

Chelonoidis niger (Galápagos giant tortoise)

I frequently got on their backs, and then giving a few raps on the hinder part of their shells, they would rise up and walk away;—but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.

The only tortoises we saw were in the The Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora on Santa Cruz Island. This subspecies, above, has a saddleback shell, an evolutionary adaptation that provided the ability to reach higher edible vegetation.

Blue-footed booby

Sula nebouxii (Blue-footed booby)

Darwin wrote of the booby and the noddy:

The former is a species of gannet, and the latter a tern. Both are of a tame and stupid disposition, and are so unaccustomed to visitors, that I could have killed any number of them with my geological hammer. The booby lays her eggs on the bare rock.

On Isla Española, I walked within arm’s reach of the blue-footed booby above straddling a chick whose pink skin was only lightly covered with linty down. The booby was so unmoved by my presence that I felt invisible. Staring into the bullet-hole pupil of a booby’s pale-jade eye, I found myself moving my head to see if it would track me. It didn’t.

Sula nebouxii (Blue-footed booby)

While a male blue-footed booby will use its brightly colored feet to attract a mate, I saw many of them alone, slowly raising one foot at a time and tilting its head to admire his own feet. When sunlight hit their feet, the reflection gave the white feathers of their underbellies a pale, mint-toothpaste glow.

Masked gannet

Sula dactylatra (Masked gannet, masked booby, blue-faced booby)

Darwin: The gannets, sitting on their rude nests, gaze at one with a stupid yet angry air.

Galápagos hawk

Buteo galapagoensis (Galápagos hawk)

Writing of the “extreme tameness of the birds,” Darwin notes:

…all of them are often approached sufficiently near to be killed with a switch, and sometimes, as I myself tried, with a cap or hat. A gun is here almost superfluous; for with the muzzle I pushed a hawk off the branch of a tree.

Galápagos sea lion

Zalophus wollebaeki (Galápagos sea lion)

Although Darwin made no mention of the fur seals or sea lions of the Galápagos, he voiced his disdain for them eight months earlier on the Chilean island of Chiloe:

On the way the number of seals which we saw was quite astonishing: every bit of flat rock, and parts of the beach, were covered with them. They appeared to be of a loving disposition, and lay huddled together, fast asleep, like so many pigs; but even pigs would have been ashamed of their dirt, and of the foul smell which came from them.

At San Cristobol, I spent hours snorkeling. When I dove and swam along the bottom, a couple of sea lion pups would pass by, disappearing as quickly as they had appeared. But if I swam in loops and spins, two or three pups would join in swimming loops and spins around me.

On one occasion, as I was swimming just below the surface, a lone juvenile sea lion came slowly straight toward me staring steadily at me with eyes as dark as old motor oil. When it was about an arm’s length away, it bared its teeth, snapped its jaws, and turned suddenly away. For a moment, all I could see in the frame of my mask was its dark flank, and then there was only limpid turquoise water. I spun around, but in that instant the sea lion had disappeared.

Zalophus wollebaeki (Galápagos sea lion)

There was a single tree in the center of Isla Lobos. Sea lions huddled in the shade of its canopy. The dappled light fell across a mother nursing her pup. Still wet after climbing out of the water, her fur was as smooth and as bright as polished bronze.

Waved albatross

Phoebastria irrorate (Waved albatross)

On Isla Española, a pair of albatrosses faced each other in a mirrored dance, beaks swaying to the side then pointing upward while making raspy whistling sounds like poorly played flutes. The well-synchronized moves ended with a clattering swordplay of their beaks.

Three feet from the path we walked, an albatross was sitting on her nest. Her eyes, wide set and under the deep brow of alabaster white feathers, had a doleful, world-weary look. She lifted herself and turned her head to the side to look at the marbled egg that lay between her pale blue legs. On the other side of the path was a clearing a few dozen yards long leading to a cliff at the water’s edge. An albatross at the downwind end of the runway unfolded his wings and ran into the wind. By the time it reached the cliff, it had enough speed to get airborne and rose quickly in the updraft coming up from the water.

Galápagos brown pelican

Pelecanus occidentalis urinator (Galápagos brown pelican)

We paddled from Gardner Bay west along Española’s northern shore, a ragged tear of black bluffs, splattered white where birds had found places to perch. A pelican with pale blue eyes rimmed in red preened its feathers while I drifted by a paddle-length away.

Magnificent frigatebird

Fregata magnificens (Magnificent frigatebird)

Dagger-pointed wings of frigate birds carved circles in the sun-blanched arch of sky above the cove where VISION was anchored. Dozens of them had settled in the tangled branches of low trees along the shore, their ebon feathers glowing with green and purple iridescence as they puffed up their strawberry-red gular pouches to attract mates.

Galápagos greater flamingo

Phoenicopterus ruber (Pink flamingo)

On Isla Floreana there was a lagoon occupied by a dozen flamingos. There are only a few hundred of them in the archipelago and we were lucky to see them. The chicks are born with gray feathers; the pink develops over time from the carotenoids in the brine shrimp and algae they eat.

Galápagos heron

Butorides sundevalli (Lava or Galápagos heron)

I slowly and quietly walked toward a Galápagos lava heron that seemed to be asleep while standing next to a ledge of lava. I was 5′ away when it opened its eyes, at least the one facing me. I stopped, and a few seconds later the lower eyelid slowly rose up and closed.

Sally Lightfoot crab

Grapsus grapsus (Sally Lightfoot crab)

Sally Lightfoot crabs seemed to have extraordinary vision and when I approached them they quickly skipped over the rocks, even leaping the gaps between them, a shyness that was unusual on the islands. They got along well with the marine iguanas, which were content to let the crabs crawl over them. I saw one crab plant an icepick-sharp leg on an iguana’s eyelid without it flinching. The crabs feed on the iguana’s parasites and dead skin.

Galápagos prickly pear

Opuntia galapageia (Galápagos prickly pear)

This opuntia is one of six subspecies endemic to the Galápagos Islands. It is a tree-like prickly-pear cactus with the rust-red scaly trunk of a madrone. Land iguanas, like the one on the rocks, can’t reach these cactus pads, but there are five other endemic opuntias that they can feed on.

Palo Santo tree

Bursera graveolens (Palo Santo tree)

On Isla Floreana, the soft-shouldered hills are veiled with a tattered lace of palo santo trees, which leaf out only during the rainy season, January to April.

Gray matplant

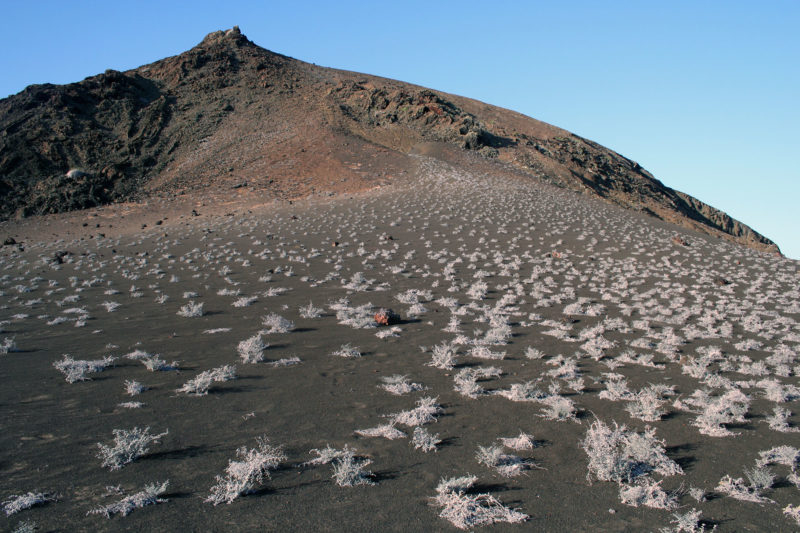

Tiquilia nesiotica (Gray matplant)

The highest point on Isla Bartolomé is a volcanic cone flecked with gray matplant, hoarfrost-white and just as fragile. The matplant, a Galápagos endemic, is a pioneer plant—life taking hold on ruptured earth. A boardwalk leading to the summit left the surrounding ground unmarred by footprints.

Bartolomé and San Salvador

Darwin wrote that the islands of the Galápagos archipelago “rise with a tame and rounded outline, broken here and there by scattered hillocks, the remains of former craters. Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance.”

With the sun rising behind me, I stood on the summit of Bartolomé looking northwest to San Salvador and watched the morning light bathe an unspoiled primordial landscape. It was like looking out over Eden.![]()

Lovely!

Your article on Darwin was quite funny and showed a side of him that I hadn’t seen even a hint of in On the Origin of Species. On reflection, it’s entirely possible that his crankiness is there, too, but that I couldn’t see it for my amazement at both his genius and the number of words he could write about pigeons.

I enjoyed your story and especially the amazing photographs from your trip to the Galapagos. They brought back some wonderful memories for me as I was so very fortunate to have been able to go to the Galapagos in 200p. Back before this kind thing was so commonplace and everyone was able to livestream every minute of their lives from any part of the world, I managed to send back nearly daily journals during my time there including one via a rather interesting encounter near Tagus Cove.

Thank you for this article. Decades ago, my family donated annually to the research station on the Galapagos and in return received a periodical newsletter (mimeographed!) of the work they did there. One time I even applied for a job to help eradicate invasive species on the Galapagos… didn’t get it though. A visit to these isles has been on my bucket list my entire life.

Those look like Feathercraft inflatables, your thoughts on that model would be appreciated.

Thanks,

Barry

The Feathercraft inflatable sit-on-tops were a good choice for the Galapagos and for novice kayakers. There were only a few experienced kayakers in the group, so we paddled slowly and the conditions were calm, so the kayaks were never put to the test. In the equatorial heat, we had to partially deflate the kayaks whenever we landed for a long stay ashore. Pulled out of the water, they would heat up and the air in the chambers would expand, possibly to the point of bursting them.

Feathercraft made very good kayaks and were leaders in creating kayaks for paddling places accessible only by air. The company closed in 2016 but the website remains active and parts are available to keep existing kayaks in use.

Nice article, and what a special place! We took our honeymoon there in 1999, rented a room at the Red Mangrove Inn in Puerto Ayora and hired a guide to explore Santa Cruz and took day trips to the neighboring islands. Nowhere else in the world can you get up close to such unique creatures and get to swim with seals and Pingüinos.