"Arrfff! Arrfff!”

This was the sound of a large gray seal as it poked its head out of the water and looked in my direction with unabashed interest. Now, I love seals as much as anyone and relish my regular encounters with them while I’m rowing on the river near my home in South Devon, England. But this was different. This seal was swimming in the Atlantic Ocean, eight miles off Land’s End, and I, rather than being safely ensconced aboard my skiff, was bobbing about in the water in a semi-inflated dry suit, just a few feet away from it. And, was it my imagination, or was this seal much, much bigger than the ones back home?

After a few moments’ contemplation, the seal sighed and slipped under the water again. A feeling of relief was quickly followed by unease at the thought that this huge creature was now swimming somewhere beneath me and I had no way of knowing where it was or what it was going to do next. Even though I knew a seal was highly unlikely to hurt me, my instincts told me a different story. So I crashed about and made what I thought were suitably macho seal noises.

“Arrfff! Arrfff!”

Almost immediately the seal appeared on the other side of me, and once again gazed at me with those big dark eyes. I had assumed it was a male seal protecting his territory, but it occurred to me then it might be just trying to be friendly, or possibly more. Perhaps a bright yellow dry suit holds an irresistible attraction to an ocean seal, normally sheltered from modern pinniped fashion trends.

Our moment was interrupted by the appearance of Will Stirling’s 15′ dinghy suddenly looming large with her bold cream-colored lugsail. The seal glanced over, its eyes bulged open in alarm and, with a grunt, it dove underwater. It didn’t reappear again, and I was relieved when Will luffed up beside me and I was able to clamber out of the water to safety.

The incident took place while I was a participant in Will’s madcap plan to sail around every offshore lighthouse in Britain. The project began in March 2012 when he and his wife Sara sailed around the Eddystone Lighthouse, 13 miles south of Plymouth, in a 14′ open dinghy. The couple did that trip to raise money for WaterAid, a global nonprofit devoted to bringing clean drinking water and hygiene education to disadvantaged communities, and the idea grew from there. Will’s scheme is an ambitious one, not least because of the sheer number of offshore lighthouses—at least 50—but also the remoteness of some, for example, Sule Skerry is 35 miles north of Scotland. But Will isn’t in any hurry, and regards it as a lifetime project.

By summer 2017, he had ticked six more lighthouses off the list: Les Hanois in Guernsey, La Corbière in Jersey, Godreavy near St. Ives in Cornwall, both lighthouses on the isle of Lundy in the Bristol Channel, and the Longships off Sennen, Cornwall.

In one 120-mile voyage he tackled two lighthouses, Les Hanois, and La Corbière in a 14′ open sailing dinghy, a type he has been building at his boatyard for the past 15 years, but an incident during that journey convinced him he needed something a bit more seaworthy. He and a crew member were off Jersey, hanging onto a mooring buoy to hold their positon in a strong adverse current, and almost capsized the boat. Will decided there and then he needed a boat that could cope with a greater angle of heel.

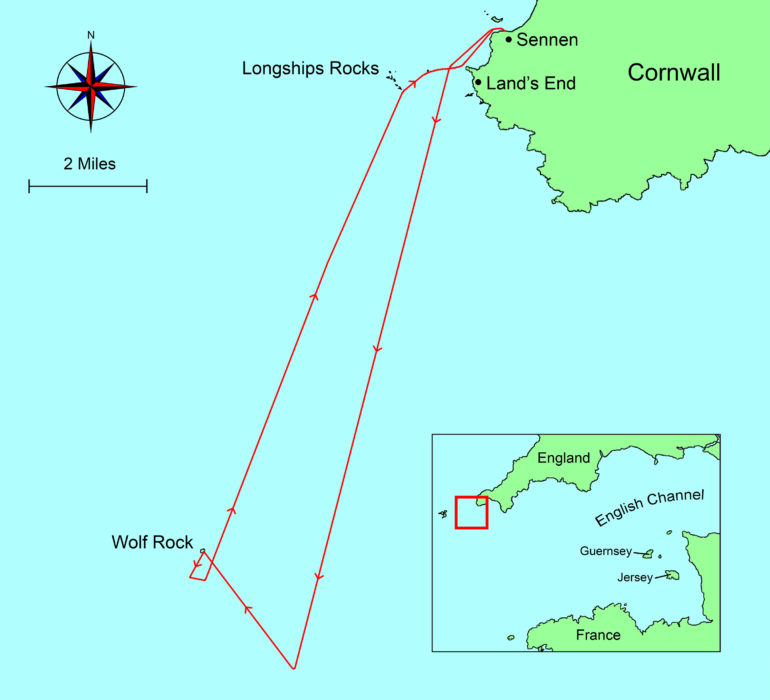

The result was GRACE, his 15-footer with side decks and a cockpit coaming all around to keep the water out, and an extended foredeck to give more shelter to anyone sleeping in the bow. I joined Will for the second attempt on his eighth lighthouse: Wolf Rock, 8 miles off Land’s End at the westernmost tip of England. He had to abort his first attempt because of bad weather, and indeed our departure was postponed when a Force 5 headwind and driving rain appeared on the appointed day. The next day, however, the clouds cleared and, after rejecting several possible launching places on the south coast of Cornwall, we finally launched GRACE at Sennen on the north coast, which we judged would give us a better sailing angle in the west-northwesterly winds that had been forecast.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonLeaving Sennen, Will keeps an eye on the sail as we round the end of the breakwater. His 15’ Expedition Boat was a development of his standard 14’ dinghy with side decks and a longer foredeck added to provide more protection from the elements.

Sennen is a picturesque Cornish village, popular with vacationers and surfers alike. At its western end is a beautiful little stone harbor, whose main claim to fame is being the most westerly harbor in mainland England. It is still used by a fleet of fishing boats that are dragged by tractor up and down the beach for launch and haul. A steep slipway runs down from the parking lot to the beach, which made launching the 500-lb boat slightly treacherous. The last time Will launched the boat here, his van couldn’t cope with the gradient and had to be towed up by the tractor.

Will is one of these very organized skippers who’ll send you a passage plan several weeks in advance, complete with course information, estimated timings, local tides, times of sunrise and sunset, and even the phase of the moon. He is also reassuringly safety conscious, and brought along all the essential safety gear in a waterproof bag, including EPIRB, GPS, VHF, compass, and flashlight. All I had to do was turn up with my lifejacket, a dry suit, a packed lunch, and a waterproof camera.

A light northwesterly breeze was blowing as we headed out of Sennen at 11 a.m. sharp, 30 minutes ahead of Will’s schedule. The Cornish coast is famously rocky and thousands of shipwrecks litter its shore; we were put straight to work just off the harbor entrance negotiating a reef growling ominously to windward. We cleared it without any trouble and a few minutes later passed one of the most dangerous rocks along this whole coast, the infamous Longships, the site of dozens, if not hundreds, of shipwrecks. Even after a lighthouse was erected there in 1873, that didn’t stop the 282′ steam-powered coaster BLUEJACKET being driven onto the rocks just a few yards away from the lighthouse, nearly destroying it in the process, on a perfectly calm, clear night in November 1898. The crew was saved but their embarrassment was never-ending.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingHaving overshot Wolf Rock on the previous tack, we approached it from the southeast. The east-going tide added about 45 minutes to our crossing, as we had to claw our way back.

Given the fearsome history of this coast, it might seem foolhardy to navigate it in such a small boat, and certainly the sight of those shadowy cliffs rising dramatically on our port side made me feel very small and insignificant indeed. But there were definite advantages in having such a diminutive steed. For a start, we wouldn’t have been able to sail between the rocks and the shore on a bigger boat, and would have had to take a longer route around the seaward side of the Longships. And even if we had hit a submerged rock with the dinghy, in most cases it would have been a case of simply raising the centerboard and sailing into deeper water, something that was definitely not an option for the unfortunate BLUEJACKET.

Will had a more philosophical take on going to sea in a dinghy, quoting first a great poet and then a great explorer: “As T.S. Eliot said: ‘Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.’ To start with I didn’t know the capabilities of the boat or myself. But with each trip I’ve got more confident and realize we can do this. My planning’s got better too, because that’s the key. And as [Roald] Amudsen said: ‘Victory awaits him who has everything in order—luck, people call it.’ You have to be prepared, and then hopefully you can sort out whatever’s thrown at you.”

Land’s End. The very words conjure up a feeling of foreboding, and before Europeans discovered America it had a much more literal meaning. Nowadays, while the cliffs are as dramatic as ever, with clusters of fierce-looking rocks peppering the coast, the overall impression is slightly marred by a hotel and tourist developments that look anything but wild.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

By the time we passed Land’s End, a quarter of a mile off to port, the Wolf Rock lighthouse was clearly visible as a faint finger on the horizon, 8 miles to the southwest. For centuries, the semi-submerged rock that the lighthouse rests on presented a hazard to shipping passing around Land’s End. A local diver estimated there are at least 100 wrecks between the rock and the mainland alone. From 1795 onward, four attempts were made to erect a beacon on the Wolf, all of which were smashed to smithereens by the sheer power of the Atlantic waves. Finally, in 1848, a 14′-high cast-iron beacon filled with concrete rubble was built and held fast. In 1861, work started on an elegant 135′ tower modeled on the Eddystone lighthouse. It took eight years to build, with work interrupted by severe weather and brutal waves. The new light was first lit in 1870 and operates to this day, sending out a single white flash every 15 seconds when darkness falls.

It was bright sunshine as we headed for the Wolf—so named because of the howling noise the wind makes when it blows through the islet’s fissures—and GRACE seemed to delight in the steady westerly Force 3 breeze. It was certainly a fine day to be out at sea on a small, exquisitely built wooden boat, with the sun high in the sky and the water just a few inches away. Behind us, the rocks of west Cornwall receded into the distance, while ahead of us lay what looked like an endless expanse of sea. Next stop, the Azores.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonWolf Rock was the first lighthouse in the world to be fitted with a helipad on top of the tower.

We were soon surrounded by wildlife, another advantage of traveling by sail in a small boat. An endless array of seabirds passed us by; the ubiquitous gannets, a Manx shearwater, and what I took to be a black tern, went about their business without the slightest concern for the little wooden cockleshell in their midst. Halfway to the Wolf, I spotted a big, floppy fin straight ahead and steered GRACE to leeward of it. It turned out to be an ocean sunfish, a strange-looking white slab of a fish, as tall as it is long, that seems to be all head and no body or tail. It seemed reluctant to interrupt its sunbathing and only dipped down under the surface at the last minute, passing so close we could have touched it.

Soon after, I spotted some strange splashes in the sea about 200 yards off our starboard bow. Eventually I could identify the commotion as some dolphins, but far from being the being the playful, friendly sort who come and frolic off the boat’s bow, these guys were hard at work apparently using shock-and-awe tactics to confound a shoal of fish. We passed by unnoticed.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonWith the boat anchored off Wolf Rock, Will swam ashore with our cameras, phones, and VHF in a dry bag.

With the Wolf Rock light drawing closer, Will made a strange confession. As he described his previous trips on the boat, he admitted that none of his crew had come back for a second go, so each trip had to be done with a new crew. That gave me pause for thought. I was crew No. 8.

With the wind backing to the west and a stronger-than-expected current setting us to the east, we weren’t able to make it to the Wolf Rock in one tack. Instead, we overshot it and took a few short tacks to windward, and soon the lighthouse began to loom large over the port bow, its elegantly tapered tower making a distinctive L shape with the rock below. One of the rules Will has set for himself is to sail completely around every lighthouse on the list, so we rounded the Wolf to port and made a counterclockwise circumnavigation, and then dropped anchor in a small cove in the lee of the rock.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingCan’t go over it, can’t go under it. The only way to get ashore safely was to go through the wash. We floated onto the rocks in our dry suits, relying on their buoyancy to keep us afloat.

Anchored about 50’ away from rocky islet, we were faced with the same dilemma the builders of the lighthouse and its subsequent keepers faced: how to get on and off it. Even in the relatively benign conditions of that sunny August day, a big swell surged around the rock, rising and falling about 6’ and creating swirling eddies. Back in the days when the lighthouse was manned, the keepers came up with ingenious ways of transferring people and stores from ship to shore, including using a kite to fly a line out to the relief ship. Once the ship was in position, the men put their feet in a bight in the line and hung for dear life as they were winched on or off the rock.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingThis ledge seemed to be a favorite sunbathing spot for seals. They scampered away when they saw us. The 1848 beacon is visible on the left. The landing area between the beacon and the lighthouse built in 1870 was a key part of the building the towers, as well as making it easier to get keepers and stores on and off the rock.

Judging by news clips from 1950 and 1952, it was pretty hazardous in good weather and completely impossible in bad, which meant the keepers often went weeks on end without supplies or a relief crew if a storm was blowing. The problem was finally solved in 1972 when a helipad was built on top of the lantern, the first lighthouse in the world to be modernized in this way. Once the lighthouse was fully automated in 1988, there was no need to transport keepers or bring supplies.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonWill climbed to the top of the 1848 beacon. Made of cast iron and filled with concrete rubble, it was the fourth attempt to build a light on Wolf Rock–all the others were swept away by the power of the waves.

Our solution to the problem of getting ashore was simpler. With the dry suits zipped up, they provided enough buoyancy to more or less float us over to the rock. Then it was a matter of choosing the right rock and the right wave, washing onto it, and hanging on for dear life as the water rushed out again. Will went first with the VHF and cell phones in the dry bag (in case the dinghy were swept away while we were on the rock), and I followed behind slightly apprehensively.

Will Stirling

Will StirlingThe Trinity House logo, cast in bronze above the main entrance, includes its motto Trinitas in Unitate—Three in One.

It was certainly more tiring than it looked, and by the time I had flapped my legs and arms at full tilt to navigate from boat to rock (pulling a leg muscle in the process, as I discovered the next day), then scrambled up the rocks and climbed up the platform sides, I was puffed out. That only added to the sense of achievement, however, as we stood there and gazed over what was really a different world.

The base of the lighthouse forms what must be one of the strangest mooring docks ever built, with rings to attach lines to, steps at the northern end (away from the prevailing winds) and the remains of the crane used to hoist those keepers and parcels onto the rock. Everything is covered with an even layer of barnacles, like a giant’s sandpaper, a reminder that everything we were standing on is submerged for much of the time. To one side, built into the concrete dock, is the 1848 beacon, a specter from the past, squat and defiant, an embodiment of man’s struggle with nature.

Standing guard over all of this is an almost dainty lighthouse. You would hardly believe this lofty structure is made up of 3,300 tons of granite, tapering from 41′8″ at the base to 17′ at the top, and completely solid for the first 30’. Above that, the walls of the hollow section are tapered, starting 7′9″ thick and gradually thinning to 2′3″ at the top—every external stone dovetailed not only to the ones on either side to it but the ones above and below it. It’s poetry in granite, and a complete contrast to the stumpy, rubble-filled beacon built 20 years earlier, yet equally able to withstand the might of the Atlantic storms.

When Will climbed the bronze ladder rungs to reach the lower front door of the lighthouse, he found it too was made of solid bronze. Above the doorway, also cast in bronze, is a bas relief of four sailing ships on a shield and the words Trinitas in Unitate—Three in One. It was the coat of arms of Trinity House, a charity devoted to maritime safety, responsible for all lighthouses built in England and Wales since 1514. Its motto is a reference to its original purpose of running lighthouses, providing pilotage, and serving as a charity for distressed sailors. It’s as if the builders recognized that, even in this harsh environment, a decorative touch would help ease the burden of the unfortunate souls confined to this inhospitable place for months on end. Sadly, this grand entrance has been blocked on the inside since the construction of the helipad.

We clambered around the rocks and a herd of seals sunbathing on the south side of the rock squirmed back into the sea when they caught sight of us. I climbed down to where they had been and was surprised to see a rainbow on the side of the lighthouse: dark brown barnacles at the bottom merging with the bright green seaweed which became yellow where it was dry, followed by pinky brown granite which became black at the top. Even in this most austere of places, nature performs its magic.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonIt was while photographing GRACE from the water, to provide documentation that Will had actually sailed around the lighthouse, that I had my close encounter with an amorous seal.

The wind was easing, and we were all too aware that if it died altogether we would have to row the 9 miles back to Sennen. So, about 20 minutes after we landed, Will swam back to the boat, while I swam farther out to sea to take pictures of GRACE sailing past the lighthouse—proof that we had indeed sailed there and that he could tick it off his list. It was then that I encountered my overly friendly seal. And to those who might scoff at my trepidation, I say: you weren’t swimming out at sea with a large sea mammal making unwanted advances.

Nic Compton

Nic ComptonA stronger-than-expected west-going current swept us off course and pushed us onto the infamous Longships Rocks (visible behind Will). Some committed rowing was required to get us past the rocks and into a more favorable current.

Having been rescued by Will, and with both of us safely back aboard GRACE, we set course for Land’s End. As we feared, about halfway back the wind died and we were forced to bring out the oars, first Will rowing on his own with me at the helm, and then the two of us rowing side by side, each wielding an oar. It was at this point we realized we had misinterpreted the tidal charts and underestimated the strength of the west-going current, which had set us nearly half a mile west of our intended course. It doesn’t sound like much, but it meant we had to row straight into the current to stop ourselves being swept onto the Longships rocks, and added nearly an hour to our time. Once we were inshore of the Longships, however, we found a favorable tide which swept us back to Sennen.

The sun was setting as we pulled the boat out of the water and packed our gear. Our total journey time was 9 hours, quite a bit longer than the 6 hours Will had estimated in his passage plan, but then the wind was considerably less than forecast and we had had our mishap with the tidal charts.

Next on Will’s list is the Bishop’s Rock, 29 miles west of Wolf Rock, which guards the western edge of the Isles of Scilly. Would I be tempted to join Will again and become the only person to crew for him more than once on his madcap quest? Without a doubt.![]()

Nic Compton is a freelance writer and photographer who grew up sailing dinghies in Greece. He has written about boats and the sea for more than 20 years and has published 12 nautical books, including a biography of the designer Iain Oughtred, available at The WoodenBoat Store. He currently lives on the River Dart in Devon, U.K. He previously wrote about his adventures in his Western Skiff.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

As a dinghy sailor from yesteryear, I just love this story. Coincidentally I am just finishing Bella Bathurst’s book, The Lighthouse Stevensons. After a lengthy absence I have taken up sailing again, also being a crew member on a whaleboat and restored lifeboat here at Port Fairy Victoria Australia. Again I just love the story and the photos. Thank you very much

Hi Jan, Glad you liked the story. The Stevensons are certainly a fascinating clan who between them saved hundreds of lives. Where would we be without them! Happy sailing, Nic

What a great story! I know Will (I work at Sara’s yard,) and I have to say I’ve met very few determined people such as Will, and yes, I’ve heard a few tales from previous crew! Well done on not becoming “known” by the seal, excellent piece of writing and some great photos.

Well done guys! Nice story and Will, as always, is doing well! Greetings and appreciation!

Looks like fun. I’ve paddled to many of Maine’s island lights but circumnavigation hasn’t occurred to me. Maybe something to do with the new ride RAMONA, which is well tucked up for the winter. Haven’t run the 18 miles out to Matinicus for years, last time a night paddle. Thanks, Nic.

Hey Ben, you better make a list of lighthouses and start ticking them off!

The boy inside, in contrast to what appears to be a 60-year-old man looking back at me in the mirror, was hanging on every line of this adventure. My gears were turning as I read this well written and well illustrated story, and I look forward to small wooden boat adventures of my own. Excellent work Nic! I hope you grace these pages again.

Great story, Nic. Amazing photos and Will’s ambition, slightly mad-cap, is actually rather exciting. Good on you both. Thanks for an enjoyable article.

Could someone give me the dimensions of GRACE. I think I would like to build one like that.

We provided a link to our review of the boat in Nic’s story. Here it is again:

https://smallboatsmonthly.com/article/15-sailing-dinghy/

GRACE is 15’ long and has a beam of 5’ 2” and a sail area of 130 sq ft. She’s a Sailing Dinghy built by Will Stirling of Stirling and Sons in Devon,England.