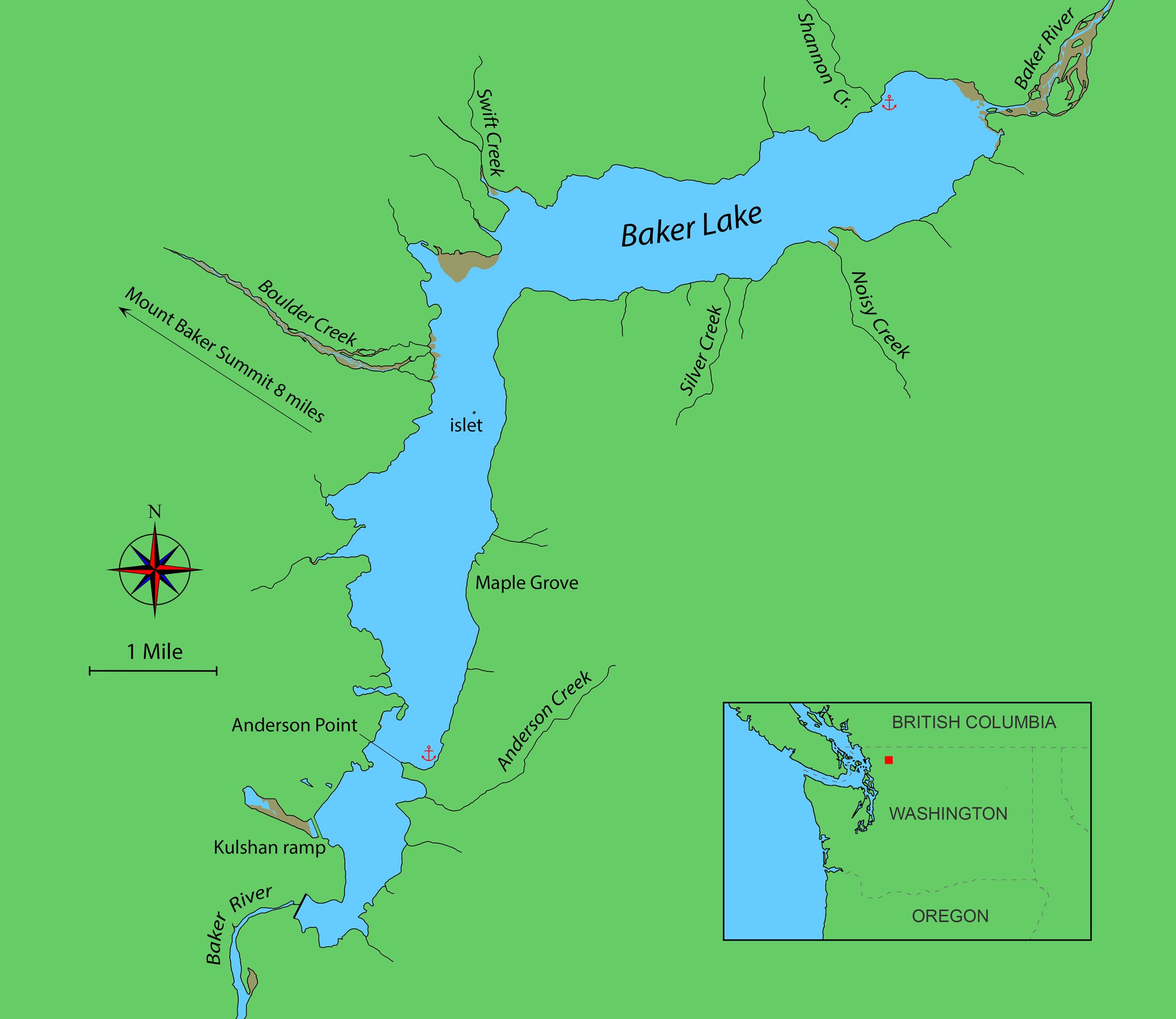

Mount Baker was all but invisible from the ramp at the south end of Baker Lake, just 10 miles from the summit, the third highest in Washington. A pale gray overcast had wrapped around the volcano’s 10,781′-high summit and the diffuse afternoon light had blended the snow fields and glaciers with the clouds. Only a few jagged obsidian-black lines—bare rock faces angled toward the peak—betrayed the presence of the mountain.

It was midafternoon on a Wednesday in May, more than a week before the start of the summer camping and fishing season, and my 17′ garvey cruiser, HESPERIA, was the only boat at the ramp. The level of the lake, a reservoir created by a dam hidden around a forested point of land to the south, was down by at least 10′, and only the last 20′ of the dock was afloat. The rest of the molded plastic sections lay on the ramp like discarded mattresses.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe cove at Anderson Creek was one of the only places on the eastern shore that looked like a suitable anchorage.

I rowed out into the lake and headed for the east shore. It was the less-developed side of the lake where there were only walk-in campsites. Just 0.6 mile from the ramp I reached a slender point of land where a row of trees, evenly spaced and straight like the teeth of a comb, had been blackened by fire. The side of one tree, as thick as a telephone pole, had its bark turned to a 12′-high face of cracked and buckled charcoal.

Anderson Creek was picturesque but rather noisy.

I rowed into the bay nestled on the north side of the point and poled ashore at the mouth of Anderson Creek. A gravelly bar 30 yards long, tapered and hooked like a shark’s dorsal fin, guarded the mouth of the creek, which tumbled in a white froth over and around a streambed of speckled granite boulders. The little cove would have made a good anchorage, but while the sound of the waterfall was pleasant, I didn’t think I’d be able to fall asleep to it.

I rowed around Anderson Point and headed up the shore. There wasn’t another cove anywhere near and I turned back to the creek to settle in for the night. There were two snags sticking out above the water, one a boat-length from shore, the other about 100’ farther out. I decided to secure HESPERIA between the two. The weather report had been for very light winds, 4 mph or less, and I didn’t need the protection of a cove.

I tied one of my 75′ anchor rodes to the snag farthest from shore and paddled to the other as I paid out the black rode. When I came to its end, I tied in the white rode and made my way to the other snag. I pulled HESPERIA out to the middle of the lines and tied the painter in with a Prusik hitch.

For dinner, I set the grill on the cabin roof and toasted a boxed pizza while I watched the daylight slip from the lake. A beaver swimming out from shore showed only its snout and the curve of the back of its head, looking like a motorized model of a torpedo-stern runabout. It turned around and swam back to shore into the dark reflection of the trees, its wake a trail of silver slivers of reflected sky light.

The flanks of the mountain were growing dim but for one soft-edged patch glowing in a light reflected through a hole in the cloud layer blanketing the top of the mountain.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The evening had turned cool so I started a fire in the wood stove and soon a dusty, dry heat filled the cabin. When it was getting too warm, I pushed the cabin-roof hatch cover back and as the heat escaped I felt the cool air drawn in through the open ports in the cabin side. I set up the sleeping platform and cushions and spread one sleeping bag over them, laid down and pulled a second sleeping bag over me. The stove was down to embers and a tangerine glow from the mica window lit the cabin. In the stillness that surrounded HESPERIA, the faintest sounds in the cabin weren’t made inaudible by any other noises. The stove, cooling as the embers dimmed, creaked several times before falling silent. Bubbles in what was left of the can of seltzer I’d opened were snapping; I drank the last few sips to put an end to the racket. For a while I wondered if the sound of my breathing would keep me awake. The cabin cooled and I pulled the third sleeping bag over me and I was soon asleep.

When I woke in the middle of the night, the lake was illuminated by starlight and the only featureless black was the forest on the far side of the lake, ruler straight across the bottom, its top edge crumpled. Mount Baker’s snowfields were bright enough to bring the mountain out of its silhouette. The overcast had cleared and the mountain had shed its veil but for a wisp of a cloud trailing from its summit.

The summit of the mountain caught the first rays of the morning light.

At the first hint of the morning light the windows on the side of the cabin facing shore were dark, indistinguishable from the cabin wall, and those facing the open lake were four rectangles of iron gray. I checked the time on my phone, it was 4:48. Five minutes later, the soft quavering whistle of a songbird brought an end to the night’s silence. Soon, the summit of the mountain caught the first of the light spilling over a hidden horizon to the east and glowed a cotton-candy pink.

It took a dozen strokes to get HESPERIA and her load of cruising gear going. I rowed north making close to 3 knots and leaving a winding trail of bubbles. The water around the boat was flecked with cinnamon-colored pine needles and, just offshore, driftwood was scattered all across the lake as if a high tide had cleared the beaches of scraps of wood. I rowed past what must have been a stump floating upside down. Its silvery gray tangle of roots had long ago been stripped of bark and turned into a medusan mane of serpentine locks. All along the shore, in the band of gravelly earth uncovered by the low water, there stood more fluted stumps, upright. Some bore the axe-cut notches loggers made for their springboards to get high enough above the flared bases of the trunks to cut through the thinner waists. Above the band and just 10 yards from the water were alders and young red cedar, both with their branches bearded with pale green moss.

I rowed toward a stretch of beach that appeared to be free of large rocks and stumps. I slipped the oar handles forward and coasted in. I had brought my bathyscope, thinking it would give me a clear view of whatever lurked underwater, but all I saw in its dark interior was a glowing rectangle of jade green. The shore was so steep that I could only see bottom when I was a boat length away from landing. I crawled on the foredeck, and when the bow was hanging over dry ground, I stepped ashore. The soil was loose and slumped into the water when I put my weight on it. I leaned out and tied the painter to the root of a stump just back from the water’s edge, then used the line to pull myself up to dry ground. There wasn’t much to explore. The steep, loose ground made for difficult walking and the brush at the edge of the woods was too thick to pry a way through.

I continued rowing north, still in the shadow of the steep ridge to starboard; the western shore of the lake was washed in light except for one dark arc cast by the highest peak on my side of the lake. Two geese swimming out from shore honked to one another. The echoes coming from the woods a half-second later were muffled and sounded like a pair of dogs barking a mimicked reply.

In the early morning, I rowed in the shadow of the ridge that towered over the east side of the lake. The edge of that shadow was cast on the shoreside woods across the lake just above HESPERIA.

I stopped at a low point where the shore was wider and not so steep. There was a broad stump at the water’s edge; most of its center was missing but I could pace off the width of the platform left by the loggers after they had felled the tree. It was 15’ across at its widest point and could have filled one of my bedrooms at home. I gathered some loose driftwood sticks from around the stump for firewood; some were too thick to break across my knee, so I cut them down to size by dropping a rock as big as a bowling-ball on them.

On Thursday morning, I rowed past the campground at Cedar Grove. There wasn’t wind enough to sail, and motoring seemed too disruptive to the quiet start of the day, so I rowed.

As I left, the two geese flew south, one trailing 3′ behind the other, and when I could no longer hear their honking, the only sound was the whisper of a creek hidden somewhere in the woods. The sun crested the ridge and the first rays of sunlight cast sharp-edged shadows across the cockpit. The trees covering the steep slope of the ridge were still in shadow and although the sky was clear, a soft blue haze was in the air and the trees appeared as if across a smoke-filled tavern. A breeze-borne gossamer thread gleamed white against the dark, distant slope.

I heard the rush of a power boat approaching from the south and could make out the swath of its wake spreading across the lake behind it. Even a mile away it sounded like a vacuum cleaner in the next room. As the boat raced along the far side of the lake, its wake cut a pale-blue scar across a mile of the foothills forest’s dark reflection. The boat, an aluminum outboard skiff with a pilot house, passed by me 1/4 mile off and by the time its corrugated wake hit HESPERIA—shaking the cabintop and rattling the mast and spars resting on the roof—it was almost out of sight to the north. A minute later I heard the muffled hiss of the wake hitting the eastern shore.

This mound of rocks in the middle of the lake is normally underwater when the reservoir is full. A few stumps indicate the islet was once a tree-covered hill rising more than 200′ above the Baker River valley floor.

With HESPERIA trailing only a wake of curdled water, I rowed to a rocky islet in the middle of the lake. It was only about 15 yards across and 8′ high. A sign on a post planted at the top read “Caution Shallow Shelf Area” in print too small to read at a safe distance. Aside from two age-blackened stumps the rock-strewn mound had the look of a landscape on a lifeless planet.

To feel a little less smug about my boat’s quiet passage, I climbed across the cabin roof and planted myself in the aft cockpit and fired up the outboard. There is not much space there, less than 24″ from the top of the transom to the back of the cabin. The outboard is set in a notch on the port side and I stand in the middle straddling the boat’s tiller, steering by turning my knees to the side.

To the west, Mount Baker loomed over the valley that cradles Boulder Creek, a stream that is fed by the water dripping from the ice and snow that cover the peak’s eastern slope. From the lake, Baker appears to have two summits. The southern peak is a symmetrical pyramid with one edge dotted with exposed rocks, the other a smooth slope of snow. The northern summit looks like a wheeling humpback whale—a long smooth arc with a short, blunt fin.

I had quickly covered about a mile from the islet and cut the motor so I could take some notes. As HESPERIA coasted to a stop, I felt a cool breeze on my back. I had missed it while I was underway. I started the outboard again and tuned back to take in the stretch of the east shore that I had let go by unnoticed. I went as far south as the beginning of the cat’s paws.

The breeze was light, but it was still well worth backtracking upwind under power to cover the same ground under sail.

I cut the motor, tilted it up out of the water, and HESPERIA drifted farther south into the flat calm. I climbed over the cabin, lifted the mast from the rooftop and stepped it through the partners on the foredeck. After I tied the square sail’s lower yard to the base of the mast, I unrolled the sail from the upper yard and let it drape itself over the foredeck in loose folds. When I raised the sail, there was just enough wind to belly it out from the mast and HESPERIA slipped forward. Water chuckled under the bow, and a piece of driftwood about the size of a hot-dog bun passed under the hull, tapping as it went; it sounded like the hesitant knocking of a stranger at someone’s front door.

The breeze was a mixed blessing. It gave me a chance to sail but erased the reflection of the mountain

The shore I was headed for lay east of Swift Creek and had a long stretch of low beach with a tilted head-high stump standing in the middle of it. About 50 yards out, I could see the bottom and the water was quickly getting shallower. I grabbed my long stand-up paddle, slipped between the foot of the sail and the lower yard and crawled over the foredeck. With the sail still gently pushing HESPERIA, I used the paddle to steer clear of the rocks scattered on the bottom. When there was only 1′ of water, I stopped HESPERIA with the paddle’s copper-guarded blade pressed into the bottom.

In the time I took for the break to walk the beach and have breakfast, the anchor, which I had set in dry ground a few feet beyond the water’s edge, was awash, not just with the lapping ripples but by a rise in the water level. I guessed that in sweeping across the lake, the southerly had shifted the water north.

With the sail and mast back on the cabin roof, I used my push-pole to navigate the shallows while I stood in the forward cockpit with a good view of the bottom. When the water was deep enough to reach the 6’ on the pole shaft, I moved to the aft cockpit to switch to outboard power.

I motored into the lee on the other side of the lake, just past the dogleg. I turned east and passed through what looked like a tide rip, littered with driftwood and forest debris. Straddling the tiller, I steered by shifting my knees from side to side like a slalom skier, and HESPERIA lumbered through turns around the larger logs. Where the debris was thickest, I took the moor out of gear and coasted through.

The upper half of the lake, angled to the east northeast, was calm. The forest pressed up against the shore in an unbroken palisade for the first 3/4 mile. I stopped the motor and let the boat drift around a blunt point where there was a stand of slender trees their tops bereft of foliage. Pairs of their uppermost branches, set directly opposite each other had grown at right angles to the center trunk before making tight turns to point straight up, tapering to fine points and looking like Salvador Dali’s waxed mustache.

I came ashore at the first beach I found. It was littered with driftwood, so I took my hatchet with me to gather firewood for the stove. I hoped I might find some old-growth, tight-grained Alaskan yellow cedar. Like western red cedar, yellow cedar driftwood is distinctive for its silvery color and smooth surface. I tested several pieces with the hatchet, chipping away a bit of the surface, and most were red cedar with fine grain, about 30 rings per inch, and a rich, mellow fragrance that distinguishes it from the more piquant scent of newer growth. One piece of driftwood, a lozenge-shaped piece with fuzzy blunted ends, was bright yellow and looked a little like yellow cedar, but I could rule that out with a quick sniff. The fragrance was unfamiliar, but I decided it was Douglas fir, well aged. I’m not much of a drinker, but while I was sampling the logs on the beach I felt as it I were at a wine tasting.

It was hot walking the shore under a bright sun, so when I got back aboard I set up the canopy over the cockpit before I started rowing again. In the shade, I continued along the shore, and the still air lying over the water cooled me as I rowed through it.

With the canopy keeping the heat of the sun off me, I could feel the layer of cool, still air lying on the water.

As I rowed, sunlight reflected by the water on the starboard side painted dancing patterns on the underside of the canopy. The light concentrated by the convex curl of the wake created flowing bands of light that changed shape and position in time with every stroke of the oars.

A corn-meal-yellow butterfly, about the size of a one-dollar coin, caught up with and passed HESPERIA to port. It bettered my 3 knots in spite of all its darting and dipping. At times it dropped so close to the water that it almost fell into its reflection, but it stayed aloft for as long as I could see it. It angled away to the north shore and had a good mile to go before landing there to take a rest unless it found a log along the way.

I could hear voices carrying across the water from the opposite side of the lake. I saw no camps or boats in the direction of the sound, even with binoculars. I couldn’t make out a word being spoken; only the vowels reached me and the consonants, without breath behind them, dissipated in the air somewhere over the lake.

On the near shore, I heard the rush of Silver Creek long before I reached its mouth, which was flanked by two finger-like bars of lead-gray rock and gravel. At the root of the bar on my side was a 10′-wide path that had been cleared of large rocks, a landing made by boaters in the past. Standing on the foredeck, I paddled toward it, sat down, and stepped off before the bow struck bottom. I tied the painter around a football-sized rock and walked to the undercut bank of the woods where stump, 12′ tall, leaned out over the bar. Its exposed roots were worn smooth, having been used for steps and handholds to climb the bank. At the top, some camper had lashed together a driftwood ladder with black plastic twine and left it on high ground for safe keeping.

On the high ground there was a campsite with a fire ring, a bench made of split logs, and a square, level, tent platform of compacted sand. A few yards deeper in the woods I found the trail that parallels the east side of the lake and walked east, hoping to find some nettles to cook for dinner. The narrow path was flanked by thick brush, but there were no nettles, just patches of fiddlehead ferns with their curled tips looking like green caterpillars with bronze-colored fuzz. I hadn’t ever harvested ferns before and couldn’t be certain they were the right kind or at the right stage to eat, so I let them be.

I slipped HESPERIA’s painter from the rock, shoved off, and hopped on the foredeck. HESPERIA moved a few feet out from shore and then pivoted around in her own length. Still on all fours on the deck, I noticed that the boat was heeling to port, hung up on something under the starboard side. I dropped into the cockpit and put my weight on the port rail, but when I paddled, the boat only spun around.

Leaving Silver Creek, I took a break from rowing and operated the outboard from inside the cabin. A loop of line around the perimeter of the cabin and the cockpit allows me to steer from anywhere in the boat. The woodstove is at the left, with a metal screen protecting the plexiglass windows from the heat radiated by the stovepipe.

I stepped into the water, waded to the starboard side, pulled the gunwale up, and pushed. HESPERIA slipped sideways and settled back on an even keel. A few feet away from me there was a small stump lying on its side underwater. One of its roots was sticking straight up and, on its tip, under 3″ of water, was a thumbprint-sized patch of white paint. I took a break from rowing and retreated to the comfort of the cabin for a bit of motoring.

Noisy Creek tumbled into an inlet that had been turned into a broad, sandy plain by low water in the reservoir. HESPERIA rests at the water’s edge, left of center.

Noisy Creek was only 3/4 mile farther along the shore. The cove that the creek flows into has a mouth 200 yards wide. With the reservoir running low, most of the cove was occupied by a bar of sand and gravel, which pushed the creak to a 20′-wide channel on the north side. On the east side there is a shallow dead-end channel that had once been gouged out by the creek. I set HESPERIA’s bow on the sand and walked along the creek, which flowed lazily in an emerald-green stream near the lake; higher up, it tumbled in a froth through a maze of chest-high boulders.

An obliging breeze nudged HESPERIA to the top end of the lake, where the Baker River winds through a valley in the middle of the North Cascade Mountains

Leaving Noisy Creek, I motored around its eastern headland into a breeze that was herding glassy ripples toward the end of the lake. Although there were only 1-1/3 miles left to go to the mouth of the Baker River, I took the canopy down and set the square-sail.

As I came closer to the end of the lake, I saw no sign of the river, only a 1/2-mile-wide barrier of tangled pewter-gray driftwood backed by a thicket of fluttering alder trees all of the same height as if it were cropped like a hedge. A few hundred yards from shore I dropped the sail and mast and switched to the motor. I piloted HESPERIA from the forward cockpit, standing up to scout the water ahead, holding the cord connected to the outboard’s kill switch. The water turned from lapis blue to chalkboard green—the lake-end shoals extended much farther from shore than I had expected. I steered hard to port and aimed HESPERIA back to deep water. At the north corner of the lake, where the line of alders butted up against the base of the ridge that bordered the river, I turned west, uplake.

East of the cove where I came ashore for the evening, Mount Blum, to the left in the shadow of a cloud, looms over the plain of alder trees at the mouth of the Baker River.

The late-afternoon wind had strengthened and I needed a protected cover for the night. Just 1/2 mile from the lake’s end along the north shore was a semicircular cove 50 yards wide and half as deep, backed by a copse of alders leaning at odd angles to each other. I pulled the bow up on the sand bank of the bar on the south side of the cove and tied the painter to a driftwood log.

It was an early end to the day, so I had time to relax. I took a dip in the cove, scattering dozens of inch-long salmon fry ahead of my feet as I gingerly shuffled into the cold water. I warmed up with a nap in the cabin.

I set HESPERIA up for the night with two anchor rodes—the black one tied to a root in the foreground, and a white one to a log on the far shore—and then secured the boat in the middle.

When it was time to get situated for the night, I set up the same arrangement and spanned the cove with my two rodes, with one end wrapped around a log on the beach to the south and the other tied to a thick root exposed above the bank to the north. With HESPERIA tied in at the middle of the cove, I set up the butane stove in the cockpit and heated up a dish of chicken Parmesan with pesto tortellini and watched the stream of driftwood moving along the shore.

The afternoon breeze had drawn everything that floats to the end of the lake where, hitting the dead end, the driftwood circled to the north along the 1/2-mile course I’d taken. As the eddy flowed past the mouth of the cove, some of the driftwood, large pieces and small, veered around HESPERIA, got caught on the rode, and piled up. With a short length of line, I took out the slack in the rodes and got them to span the cove above water level. I also secured HESPERIA to the line to set the boat perpendicular to the rodes. The water inside the cove was also swirling, a back eddy to the eddy, and a 10′-long split of a log and a 12′-long trunk with a root fan had set themselves against HESPERIA’s stern. Standing in the cabin hatch I used my push-pole to aim them, one at a time, at the shore and gave each a hard shove.

Still hungry, I heated up a pan of pad thai and watched the ongoing parade of driftwood inch by. With the bow facing out of the cove, I had a view across the valley of the Baker River to the 7,685′ summit of Mount Blum. A 16’ log trunk with a trumpet-bell flare of root crooks crossed within a few feet of the bow. I gave it a shove with the push pole but it didn’t go far before it veered into the gravel bar. At dusk, the breeze ceased and the gyre came to a stop. I turned in, knowing I could sleep well.

I woke in the middle of the night for a bathroom break and stepped out of the cabin to use the porta-potti in the cockpit. I stayed for a while looking up at the sky and picked out Ursa Major and Ursa Minor from the vast sprinkling of stars that I never see from my home in an urban sky. A shooting star drew its sudden slash of white light across the western sky and disappeared behind Mount Blum’s north shoulder.

At 7:02 a.m., the sun rose over that same summit and daylight angled through the windows into the cabin. I dressed and stepped out to the cockpit. The varnished foredeck was beaded with dew, all except for the curve of a finger-wide band on the sun-facing side of a loose length of white anchor rode. The light reflected from the 1/2″ line was enough to evaporate that small area of dew. The cabin roof was the opposite—its only dew was on the perimeter of the eaves and the grid of the roof’s arched beams and carlins. They had held back the warmth of the morning’s fire in the woodstove.

The water in the cove was still and a pellucid green, with the same color and eerie depth seen in the edge of a thick plate-glass door. The cobble-strewn bottom, where it was visible, had no color of its own, only subtle tints and shades of the green. Where the trees at the edge of the cove cast their shadows, the bottom was black as if deep beyond measure.

With the warmth of the morning came a slight breeze that set the driftwood in motion once again. The wind was not from the river valley at its head, and it pushed all of the drift back to where it had come from; a thick mat of it was coming for the cove.

Baker Lake is a reservoir created in 1959 when the Upper Baker Dam was finished. Before the river valley was inundated by the 312′-tall dam, the forest was logged up to the surveyed waterline, leaving countless stumps underwater.

I left the cove and rowed along the shore and across the mouth of Shannon Creek. Its alluvium spread a few dozen yards from shore, making the water there shallow, in some places barely deep enough for HESPERIA’s 8″ draft. The shallowest area I drifted over was marked by gouges left by driftwood that the wind had pushed across. One sinuous trace was as wide as the trough of a gutter; another small enough to have been made by reaching over the side and dragging a thumb across the bottom. I paddled out to deeper water where the stumps loomed like apparitions risen from the silt.

As I rowed beyond Shannon Creek, I adjusted my distance from shore according to the slope of the bare ground at the perimeter of the lake. I rowed close only where the land backing the shore was steep and the tips of the trees were arrayed in tiers at least as steep as the seats in an IMAX theater. Alders occupied the front rows just above the water; their trunks were ash gray and scarcely concealed by the airy distribution of their branches. Many of the older trees had trunks about 1′ thick that leaned out over the shore and some had manes of moss draped along their backs. Mount Baker was hidden from view, but the valley of Noisy Creek provided a glimpse of Bacon Peak’s serrated granite flank and sharp 7,070′ summit.

As I watched the mountain emerge from this point of land, I paddled past a rock outcropping that trees had wrapped their roots around.

As I approached the lake’s dogleg, I didn’t want to miss the first glimpse of Baker. It didn’t seem right to be rowing with my back to the mountain and seeing it only after it had made its entrance from behind the curtain of the lake’s steep north shore. I stowed the oars, got my short paddle, and sat on the foredeck with my heels touching the water. It took about a dozen strokes to get HESPERIA moving again and then her weight helped carry her forward. The bow transom blocks a full canoe stroke so I paddled as I do a coracle, pulling the blade straight back and then slashing it out to the side before it hits the bow. Done smartly, each stroke’s swirling puddle slaps the hull, clapping out the offbeats of the cadence.

The first glimpses of Mount Baker were specks of white that slipped through the scrim of cedar, spruce, and fir branches. Then a wedge of white emerged from the shingled leaves of a maple. I was soon afloat with the reflection of the mountain almost touching HESPERIA’s bow. I sat motionless to keep HESPERIA from disturbing the mountain’s twin.

This was how I wanted to remember Mount Baker and Baker Lake—an image made possible by being aboard the only boat on the lake.

By now, it was late morning, and I feared fishermen getting an early start on the weekend would soon be tearing across the lake. I didn’t want to see Mount Baker’s reflection splintered by their wakes, so I tidied up the cockpit and headed home.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

You need to sell the plans for that boat. I’ve said that before, and Im saying it again. Also, you’ve added many improvements since the last time you showed it here

Do you have more pictures of the boat? She looked perfect for what you were doing.

You’ll find more photos of HESPERIA in the other articles in Small Boats Magazine that feature her. At the end of the first article in the list below, there are some notes about the boat added to the end.

A San Juan Island Solo

Dammed

Getting out of Line

Dude, I like reading your words all the time, but this?

This was Really well written.

The lower peak to the left of the main one forms part of the rim of Sherman Crater, which still vents gases through several fumaroles. In 1975, there was an increase in venting that alarmed the authorities, who shut down campsites and trails on Baker Lake, and urged evacuation of residents downstream. They also lowered the lake level to mitigate any tsunami that might form from a sudden pyroclastic flow or a big lahar.

Over the years I have on several occasions seen a steam plume from west of Bellingham.

The excitement around the volcano extended also to communities on the other side of the mountain. A reporter from the Bellingham Herald interviewed a 19-year-old girl in the little town of Glacier, asking her if she feared the mountain might erupt.

She said that she had lived there her whole life, and it had never erupted, so she didn’t think it would now.

So much for taking the long view.

David,

I have heard that depending on which side of the mountain were to blow out, it will either come down the Skagit and end up in Mt. Vernon, or, plan B, come down the Nooksack and end up in Bellingham. Hoping it just stays put.

I was fishing in Shannon Lake, just below Baker Lake when Mt. Saint Helens blew, and we heard the explosion. Powerful stuff!

[Shannon Lake is 165 miles from Mt. Saint Helens. Ed.]

My ex and I were still in bed that May morning, and were surprised to hear blasting seeming to come from the Chuckanut mountains. Only later did we learn that we had heard St. Helens go boom.

My brother lives in Mukelteo (my Spelling) and my Dad went out from the East Coast to stay with him for a summer. He would take the ferry over to Whidbey Island and ride the bus around. When he came back east he would tell his son, The Admiral of the North Chesapeake, how great it was, and we planed to rent a Nordic Tug the next year. Unfortunately, the wheels came off his wagon and he ended up in a nursing home and we never got to make the trip. Thank you for bringing up some fond memories so near to this Father’s Day. As Robert Service said While the Bannock Bakes!

Why has there never been a full review of the HESPERIA? This ugly duckling certainly serves many purposes. And secondly, if she were to be destroyed, would you rebuild and, if so, what changes would you make?

Anyway, great articles and keep them coming. Always the best part of the issue.

John Labrum

Lynden, WA

HESPERIA hasn’t been reviewed because it’s one of a kind and the design is not available as finished boats, kits, or plans. The most complete description of it is in my article “A San Juan Island Solo.”

The only thing that comes to mind for a a change or an improvement, it would be creating a mechanism for raising and lowering the cabin top. I had given it some thought when I was building the boat, and came up with a system, but when I found I could move the top with my feet, I decided that was good enough. The top can get crooked and hung up, especially coming down, and the system I came up with would keep the top level while moving up and down.

The cabin roof is the same as on the old Alaskan Camper. There was a hydraulic pump inside the door, manual or electric, with four lines going out to each corner to a piston. As the weight was equal at each corner, the roof raised evenly. Spars and masts would complicate things. But the Camper was an easy up and down even for this old man (now 89!).

Alternatives would be to reuse the raising scissor jack mechanism from a hard top tent trailer.

John Labrum

Hey, an idea for an article. Instead of a travelog, give us a detailed 24-hour account of a life aboard a small cruiser. Give us the facts, good and bad, about your feelings. This, or maybe two experiences, one in beautiful conditions and one in horrible ones.

Thanks for what you do.

John Labrum

Very nice! And I too would like plans or at least measured drawings. You know, in your spare time. 🙂

This demonstrates once again that we needn’t seek out far-flung locales to find great cruising. There is something especially magical about seeing the early morning or late evening sun on steep mountain peaks. To be able to experience it from your boat is wonderful.

I enjoyed the account of your Baker Lake adventure. It was waiting in my inbox when my wife and I returned from a day of hiking at the very same place. We were surprised to find that the trail and camps on the east shore were closed because of recent cougar activity. So we hiked up the Sulphide Creek trail instead, eating our lunch on the suspension bridge over the Baker River. That east side hike is about 14 miles long with many bridge crossings over the steams that at times rage down into the lake. It is one of our favorite mushroom trips and only rarely do we have to share the trail. But, we tend to avoid the more crowded times. Some years ago we were camped at Anderson Creek when we heard a scream from what we believe to be a cat. We did not make a midnight bathroom run that night. That was in early October and might have been as nice a piece of weather in my memory. We paddled our kayaks over to Anderson and let the next day’s wind push us up to Noisy Creek. We crossed to Shannon Creek the next morning and hitched a ride back to pick up our rig at Kulshan. A nice memory.

Your timing in May was a good plan. When we were there on Tuesday, there were a few stragglers from the long weekend but quite a few jet skis. Not a sight we remember from previous years.

I don’t think you generate more comments about what you choose to write about than when you push your shanty boat off the trailer for another adventure. Another one well done.

Dallen

Thanks for the well-written story that brings you right into the moment and makes you feel like you are there, enjoying the beautiful and changing scenic vistas as the HESPERIA glides across the tranquil waters of Baker Lake. The photos of the reflection of Mt. Baker in Baker Lake are striking and wonderfully framed. Keep up the great exploratory cruising.

Every word, sir, an unmitigated joy. Thank you

A nicely done story of a likely well-deserved idyll in paradise away from the office.

As for running aground on a stump, I had a similar story while rowing a small skiff on Buttle Lake, Vancouver Island. It is also a reservoir and carpeted in remnants of large old trees. I was gliding between rowing strokes when I felt the boat glide up on something. Looking over the side I could only see 3-4′ deep water all around. It became apparent that I was stopped on top of a large flat stump. Getting off again was not easy if I wanted to stay dry (it was also early spring). I finally realized that if I crawled up into the bow, it would sink a bit deeper at that end and float the boat off. A minute or two later I was again on my way.

BTW: If you run out of lakes in Washington, there are a few large ones on Vancouver Island (post-travel restrictions) like Buttle, Great Central, Kennedy, and Nimpkish and sheltered waters in Barkley Sound (Port Alberni, BC) and Clayouquot Sound (Tofino, BC).

Christopher,

I was staying at Cedar Grove Campground. I took amazing photos and this video of your boat with Baker behind you. I even have the two geese you mentioned flying from your boat and land in front of Baker.