In 2011, in anticipation of retiring after a career as a research engineer, I decided I’d build wooden rowing skiff. I wanted a boat with traditional lines—particularly one with a vertical stem and a wineglass transom—and an easily driven hull, so the waterline would have to be longer than 12′. The 17′ Whitehall I found in the catalog of designs from Glen-L was just what I wanted.

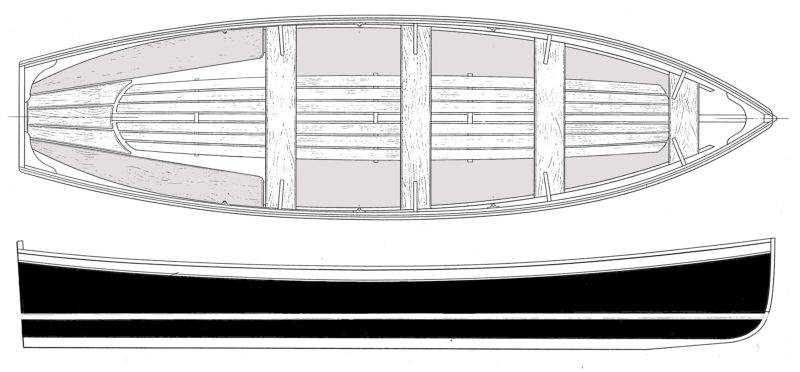

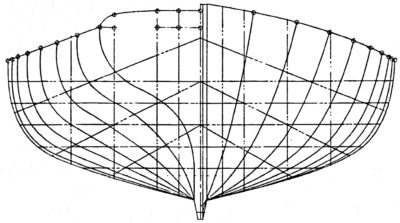

I ordered the plans, and the package I received included full-sized patterns for the molds, transom, stem, breasthook, and knees for the transom and thwarts. A table of offsets is provided, but the full-sized patterns make the offsets and lofting unnecessary. The 1/8-scale drawings show the plan and overall profile, keel profile, construction details, and lines.

For transferring the drawings to the wooden stock, I ordered carbon transfer paper from Glen L. I recommend asking Glen-L for rolled drawings, otherwise you’ll receive folded drawings. The creases in the patterns made it difficult for me to obtain precise sectional shapes. The carbon paper came with a good tip: Coat the inside of the station forms with white paint before transferring the section drawings. This way the builder always knows what controls the complex curves of the Whitehall design.

Joe Titlow

Joe TitlowGlen-L advises against lengthening the Whitehall from its designed 16′ 11″, but approves shortening it 10 percent to 15′ 3″ by reducing the mold spacing.

The Whitehall is composed of 120 planking strips bent cold over molds. The instructions suggest the hull can be stripped with hardwoods (Honduras or Philippine mahogany) or softwoods (western red cedar or Sitka spruce). The plans estimate a mahogany Whitehall will weigh about 350 lbs. My boat, STELLA, has a cedar hull with spruce trim and weighs slightly over 200 lbs. A light skiff has many advantages. It can accelerate more quickly, go faster, and be more responsive—all of that adds to the fun. At launch sites it is easy getting the Whitehall on and off the trailer, and two can easily carry it.

The instructions note that the builder can choose to use traditional glues, such as resorcinol or marine epoxy. This is just an indication of the bygone era when the instructions were written. Marine epoxies are today’s obvious choice.

I cut my planking stock from 24′-long 2×14 cedar boards. The strip construction for the Whitehall differs from the method widely used for canoes and kayaks. The strips are thicker and glued together with epoxy rather than carpenter’s glue, giving the hull greater strength, resistance to water, and durability. I put a resaw blade on my bandsaw and made 1/2″ x 3/4″ strips. The Glen-L instructions briefly discuss the option of milling bead-and-cove planking strips. Based on my experience, this is an essential step. Unlike flat-edged strips, the mated beads and coves almost snap into place, aligning themselves and closing the gaps. While you can buy bead-and-cove strips ready-made, the cost of the size of strips required for the Whitehall was prohibitive. I used a shaper to mill 5/16″-radius bead and cove profiles.

SBM

SBMThe Whitehall was designed for fixed-thwart rowing, but its long waterline and easily driven hull make a sliding seat a fitting addition.

The instructions mention the option of covering the completed planked hull with fiberglass cloth; I found additional advice in The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction. I applied 4-oz cloth with five coats of epoxy inside and out, resulting in a composite structure with a bending strength that is many times that of the cedar alone and abrasion resistance for trailering and landing on gravel beaches. The Glen-L plans recommend painting the hull, and while marine enamels will do the job, the beauty of the wood is lost. I finished my Whitehall bright, protecting the epoxy with a high-grade marine varnish.

During construction I did some things differently than called for in the plans, but I do not see these changes as fixes for shortcomings in design. I believe the aim was to keep things simple to encourage amateur boatbuilders to take on the project. Here are the refinements I made, none of them essential, and all mean more work.

Joe Titlow

Joe TitlowEven when lightly loaded, the Whitehall gives up very little waterline length.

I chose to do the strip-planking according to what the Gougeon company calls the “Master Plank Method.” It starts with the first strip laid on the midpoint between the sheer and the centerline of most of the molds (running fair across those nearest the bow) and results in a hull with the run and grain of the planks emphasizing the sheerline, which is only important with a bright-finished hull. It looks great, particularly in the bow and stern areas.

The planking strips near the keel have to run straight, so I did a “Gougeon Double Run,” which meant switching to strips applied parallel to the keel and making the transition between the two areas along a fair curve. [Editor’s note: The strips closest to the keel take quite a twist from ’midships out to each end. While the author worked all of the strips cold, steaming the ends, or wrapping them with rags and pouring boiling water over them, would help the ends come home with less strain.]

Ray Putt

Ray PuttThe Whitehall’s long straight keel is about 3″ deep and assures straight tracking. At speed here, very little wake is showing at the bow, an indication of the boat’s fine entry.

The Glen-L design shows eight laminated thwart knees 3/4″ thick. I made several knees to this design and while they were strong enough, they looked undersized on a 17′ skiff. I ultimately made the thwart knees, transom knees, and breasthook all 1″ thick, a small refinement, perhaps, but one that looks right aboard the Whitehall.

The instructions mention foot stretchers; while they’re important to a powerful stroke, I had in mind from the beginning adding a sliding seat. To support the tracks, I installed two parallel beams, secured under the three rowing-station thwarts and notched to sit flush with their tops. The beams also support the tracks for the racing-shell stretchers. This enhancement with the foot stretchers is essential for getting the maximum performance with the sliding seat.

Ray Putt

Ray PuttAs with most rowing boats with wineglass transoms, the stern is depressed with a passenger in the stern sheets and the rower amidships and coming up to the catch. Even so, the bow remains low and the hull is not badly out of trim.

I launched STELLA in August 2015. Between receipt of the Glen-L plans and first launch, I spent 1,500 hours on the project, more than half of that fairing, ’glassing, sanding, and varnishing. I spent $10,448 on the materials to build the boat.

When I pulled on the oars the first time, I was amazed and delighted with the performance of the Glen-L design. The Whitehall is easily driven, runs straight, and is stable, although initially tender. A solo rower (or sculler, more properly) can easily sustain 4 knots. The Whitehall has a beam of 4′ 6″, appropriate for oars 8′ to 9′ long. Mine are 8′ 6″. For tandem fixed-thwart rowing the stretchers are removed and then two rowers can sit on the thwarts between the tracks. It’s lots of fun with two pulling, and there’s plenty of distance between the fore and aft rowing stations to avoid a clash of blades. I have seen pictures of other 17′ Whitehalls rowed with three at the oars, so it’s possible, though we haven’t tried it. It comes down to a question of elbows and knees.

Glen-L notes that the Whitehall can carry six; we’ve only had four adults aboard in reasonable comfort and safety, but there is room for two more.

Now that we have the Whitehall, members of my family would rather row than walk on the beach, a sure sign of a good design. The boat is not too big to use as a dinghy for a larger vessel, or too small to provide a workable platform for scuba diving and snorkeling.

The light weight of my Whitehall makes it easy to move off and on the trailer. The stock trailer I bought and modified for the boat weighs about 300 lbs, so the load is an easy tow with my Mini Cooper Sport. The month following the launch of the Whitehall, christened STELLA, my wife and I trailered the boat 1,300 miles from southern California to the Wooden Boat Festival in Port Townsend, Washington. We were delighted with the positive reception the boat received by attendees and by rowing aficionados in particular. We’ve made the trip three more times since then. The Glen-L Whitehall is a great boat and a real crowd pleaser.![]()

Joe Titlow is a retired research engineer, working primarily in the aerospace industry. Besides building small boats, he constructs small buildings and furniture for his wife, two daughters, and grandchildren. Joe has owned and raced a 27′ Soling sailboat for many years, and he has been a member of the San Francisco Yacht Club for 40 years. Throughout his career he has maintained a professional interest in the dynamics of sailing vessels.

Whitehall Particulars

[table]

Length/16′ 11″

Beam/4′ 6″

Hull depth forward/2′ 6″

Hull depth amidships/1′ 10″

Hull depth aft/2′ 2″

Weight/ about 350 lbs

Displacement at 9″ waterline, four aboard with average weight of 150 lbs/945 lbs

Oars/8′ to 9′ long, 1 to 3 rowers

Passengers/2 to 6

[/table]

Plans and patterns for the Whitehall 17 are available from Glen-L.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

When I first saw this article my first reaction was “Wow, another trailer queen!” Don’t get me wrong, the builder did what looks to be a very nice job, but he ended up with a boat that is likely to be towed around to shows for a few years, where it will probably win some awards for beauty and construction. It will never win any races against anything other than equally inappropriate obsolete 19th century workboats. In time it will likely be retired to a garage for a number of years before it is offered for sale for far less than what it cost to build. Hopefully, some school or rowing club will take it off the owner’s hands for a fair price. The general shape of this boat is nice, but this boat is WAY too long, deep, beamy, and heavy to be rowed safely or efficiently by a single oarsman. Most of the time open-water rowboats have one to three people in them. Yet, this boat is almost too heavy to be carried any distance by even four people. Take my word for it, this boat probably turns like a battleship and will scare any rower smaller than Lou Ferrigno in his prime when rowed off a rough coast in high winds. That people get duped into taking on projects like this is the fault of marine publishers who haven’t offered anything new or updated on open water rowing in four or five decades. The only way to salvage this boat is to fit it with a small outboard motor. I apologize to the builder and owner of this craft for my sharp criticism. Eventually, he will come to know that every statement I’ve made is true.

“Eventually” is quite a long time, so you may “eventually” be proven right, but four years on and it hasn’t happened.

I agree, eventually is rather indeterminate. When it happens probably will have a lot to do with the builder’s professional, or lack of, professional status. If you are not forced to compete against other builders, I suppose it could be postponed indefinitely. There were so many things in this article that I found troubling that were not explained – not the least of which were the extravagant 1500 hours of labor and the stunning $10,000 in materials costs. For reasons explained elsewhere, I didn’t want to jump on an amateur builder. Fortunately, the author has responded to another’s question about the expenses and at least partially explained those astronomical numbers. Anyone who’s built a number of boats knows that it takes a while gain confidence and build speed. It also takes a while to build connections that lead to better deals on materials and milling services. I want to be clear on this, an experienced professional builder could have bought all the necessary tools, including a table saw, band saw, shaper, planer, sanders and all the materials for a boat this size for less than $10,000.00. As a designer I found it amusing that someone thought it OK that, with a sliding seat, a rower could only squeeze 4 knots out of a 17′ hull, which theoretically should be capable of better than five. Please understand this, this is not a terrible boat per se. It is a terrible boat for anyone who wants to enjoy it alone or with one other person. Again, I mainly fault the marine publishers for not updating their offerings. With access to better information, people will make better design choices.

The builder built what he wanted. He was not building to your expectations.

You are correct. That doesn’t change the facts. Presumably, some people subscribe to magazines like this to be informed. Anyone considering taking on a project like this would do well to compare this boat to all the other rowboats covered in past issues. Had this been a story about an amateur who spent a few hundred dollars and a few weekends building a clunky plywood dory I would have made no comment. This was far removed from that. Kudos to the staff at Small Boats Monthly for publishing the full range of honest and responsible comments from their readers.

Were the material costs really $10 K ?

Yes, the total cost for the boat (no oars, rowing gear, trailer, etc.) was over $10 K. The boat lumber (including delivery) was 50 percent of the cost. Varnish, epoxy, fillers, fasteners, sandpaper and all the other things that go with using epoxy came to 45% of the total. The remaining 5 percent went for plans, Meade Gougeon’s book, building and station forms, etc. Since I wanted to do a natural finished hull, I purchased top-quality western-red-cedar and Sitka-spruce boards. Included in the boat-lumber cost was a trial run at having a shop mill the bead-and-cove planking strips. That did not work out, which led me to buy my own shaper. Milling the planking strips took time, but I was very pleased with the results. The cost of the shaper (and all other tools) is not included in the $10 K.

A fine looking craft for a messabout, she looks right.

Nice work!

Kent

Looks like a stretched version of the Cosine Wherry. The lines suggest that your boat should slide quite easily through the water.

Very nice looking boat, to say the least .Well done.

As for “equally inappropriate obsolete 19th century workboats,” seems to me to come from someone who is very firm in his views of “he knows what he knows”…but does not own your boat, your experience, or your satisfaction.

From what you have written, you are happy with it in your environment and usage and I’m glad that your inputs have been rewarded by your experience.

Enjoy it!

I hope no one took my earlier comments as an attack on Mr. Titlow as either a craftsman or as a human being. My praise of his efforts was genuine. Like most of my colleagues in the professional boat design and building community I tend to give amateurs, and especially first-time boatbuilders plenty of slack and encouragement. We all remember that our first attempts were not as nice as our tenth, or one hundredth. I am, however, firm in my criticism of coastal workboat replicas and their purported suitability for recreational rowing (not sailing) and the marine publishing houses for their reluctance to print books that reflect what we’ve learned about open water rowing in the last three decades. During the 1990s on several occasions I participated in the Oarmaster Trials* an annual attempt to determine scientifically which rowboat designs are best suited for use in the coastal marine environment. During the run of the experiment (1990-1998) dozens of designs were tested. Often as many as 15 or 20 designs would show up at an event to be tested off the beaches of Cape Cod. No boats that weighed over 150 lbs. ever did well, and all those over 200 lbs. always did very poorly. The lightest boat to ever win weighed about 70 pounds. Much to the surprise of many, none of the coastal workboat replicas did well after the sub-100 lbs. boats started to appear. Perhaps an even bigger surprise is that four of the seven boats that ever won were designed by persons who are still alive! No matter what their weight or when they were designed, the most difficult boats to handle (read dangerous) in high winds were the long (15’+), high-sided ones. The notion that coastal workboat replicas are well suited to rowing for fun seems to be a mid-20th century fabrication and, indeed, is almost never backed up in the historical record. It was mostly the poor who rowed whatever boats they could get their hands on. I’m not the first to say these things. In The Common Sense of Yacht Design, L. Francis Herreshoff stated plainly that in the Golden Age of Rowing (the Victorian Era) the well-heeled regularly rowed long, narrow, low-sided, lightweight boats. The idea that most recreational rowers need boats capable of carrying a half ton of passengers and cargo is belied by the fact that couples regularly take canoe trips of two weeks or longer with no more than 80-100 lbs of gear and food. Certainly having a craft that the two of them can easily carry over a portage is a plus. That said, properly reinforced (with more than 4-oz fiberglass cloth) the Glen-L Whitehall 17 would make a fine craft for a group of energetic scouts out for a day of adventure.

* I had nothing to do with organizing, planning, selecting the sites for, or running the Oarmaster Trials events.

Would like to see author’s comments re oar selection. Really enjoyed the article!

I purchased two sets of oars from Shaw & Tenney. They are called wide blade spoon oars, 8′ 6″ in length, and made from spruce. I think S & T calls it New England Spruce, and it is about the same density as Sitka Spruce, so the oars are very light for their size. I had S & T do the sewn oar leathers and add the cherry-inlaid spoon tips. The oars are perfect for STELLA. They are long enough so that I can easily row at 4 knots, but they are also short enough that my wife and daughters can handle them. They have held up very well with almost five years of use. I treat the leathers with Oarsman Marine Tallow every few months. S & T’s varnish has held up very well, but one day they will need to be re-varnished. We visited S & T two summers ago in Orono, Maine. Well worth the trip to see oars and paddles being made.

In full disclosure, Andre seems to be selling a competing ~$6000 custom fiberglass boat of a similar design out of his company, Middle Path Boats. In fairness to Mr. Titlow and those reading this article, he should have made this commercial affiliation clear in his first reply so that all readers could take his multiple lengthy negative workboat comments in context and perhaps with a grain of salt. After careful review of both Andre’s website and this article, Mr. Titlow clearly built the right boat for himself and his family. Well done, sir.

Andre: Respectfully, you are clearly passionate about your design skills and your rowing boat. Perhaps it would be better to submit a descriptive article about it for all readers to see and let it stand on its own merits, rather than bury your personal design positions in these replies? I suspect many potential owners of future rowing craft would be interested in reading it. And it may generate the public interest you seek here for your designs.

I read all of this with some amusement as I’ve been involved in these things more than a little over the years. Andre is certainly positive and correct about his thoughts about single-seat weight, length, and rowing speed, and indeed nothing has beaten traditional Adirondack Guideboats in the Blackburn. But Andre could make his case without dissing other designs. Negative advertising seems to have become the norm in politics but isn’t really appropriate here.

Models like the Whitehall were never intended, except casually, to be rowed solo, something that you can see when you look at the rowing positions. Traditionally these boats carried passengers and were rowed by a pair. Adding a slide helps a solo rower in boat optimized for a pair. At Mystic there is the epitome of the recreational Whitehall; it has a slide, has a daggerboard, more sophisticated oar locks than anything on today’s market, etc. Under 4′ beam, over a couple of hundred pounds. She’s not intended to win races, but to take a boating party out for a fine day. Since Andre did his Skua, there are numbers of sub-100 lb. solo rowing boats out there, lots of choices, if that is what the builder wants. Main reason to go light, IMHO, is to be able to roof-rack them. And we should run an Oarmaster again, certainly doing one with pair boats. When I was doing this we found that two of us could take and hold a 17-footer easily at hull speed and we figured we could have another foot or two. My guess is something like a Thames-skiff-based design would be pretty good.

This is kind of a response to both Misters Barrett and Fuller. I do no advertising in this magazine, and hardly any anywhere else. I consider myself to be semi-retired. If someone wants one of my boats I will build them one, otherwise I’ll be happy to catch up on all the fishing I’ve missed over the years while I was in the shop. Having designed dozens of boats and built hundreds (not to mention winning a ton of races), hardly disqualifies me from offering advice. I never mentioned my company, or any success that I might have had because I just wanted to freely dispense helpful advice to amateurs the way I always have, not from on high. Now that everyone knows who I am, they are free to take my statements for what they feel they are worth. I made my professional status plain in my comments. Anybody could have Googled me! Please know that it has always been true that any potential boat builder could call my shop and ask for help whether they were a candidate to buy a boat or not. I have submitted many articles and letters to many boating magazines over the last three decades that have been printed. I challenge anyone to find one in which I’ve been seriously critical of any specific design. It has always been my policy to never publicly criticize any design or boat unless I believe that design poses a danger to the user. Reread my comments and determine for yourselves if that might have been the case here. I have also been accused of a blanket badmouthing of this design when what I said is that it has a nice shape, and that it would be nice for a club or school, but is a poor choice for the way most rowboats are used. The most consistent target of my criticism has not been either the builder or the designer, but rather the marine publishers who refuse to update their offerings on this subject. I feel I need to correct a few mistakes made by one of my critics. Adirondack Guideboats have been beaten in the Blackburn Challenge. In 1998 they were beaten by a St. Lawrence Skiff variant, and in 2014 they were beaten by a new design from the board of Ben Booth. I should also mention that at least one Adk. Gboat was brought to the Oarmaster Trials where it was competitive, but did not come close to winning. Any good lightweight, round-bottomed boat of similar size can challenge them. Since you mentioned the Skua, I’ll say that she dramatically set a new BC course record in 1995, the same year she was withdrawn from serious competition (see my company site if you want to learn why). Though she never defended her record she held onto it for several years. To that person who suggested that I write an article on Skua’s contribution to recent open water rowing history, I’ll say that I have tried to do that several times, only to be refused because I’m in the business. Now that I’m withdrawing from it, maybe some publication will be interested?

Hi Joseph Titlow,

I just happened to stumble across this review. My fiancée and I met you at Port Townsend. You gave us a little piece of wood that you milled and we took a picture with STELLA. I wanted a water-taxi like boat that can take passengers and and run with two rowers I now have a Glen-L Whitehall 17 as well! Glad to have met you and peeked at your beautiful boat at PT!

Rohit

I enjoyed reading about the Whitehall and the builders’ thoughts and processes. I also enjoyed reading all the comments and my sense is that everyone would like builders to have a boat they can enjoy. Articles like this help inform us to that end.