The Townsend Tern adroitly answers the question of whether good-looking small boats permit anything but cavelike accommodations. In the Tern, the paradox is literally one you can live with. Her attractive hull, accentuated by the lines of her plywood-lapstrake planking, still has a welcoming interior.

Kees Prins, a Port Townsend, Washington, builder and designer, designed the boat for Chelcie and Kathy Liu, small-boat enthusiasts who retired to the area. They knew what they wanted, and equally well they knew what they didn’t want. They were willing to put time into a lengthy—and therefore expensive—collaboration on design details. The boat was launched for the first time just a week before the 2010 Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival, and based on the pleased expressions of the couple, the result is on the mark.

Laingdon Schmitt

Laingdon SchmittFor a 23’6” boat, the Townsend Tern packs in plenty of the necessities of life for a cruising couple. She is designed to be simple to sail singlehanded, with unstayed carbon-fiber masts that are hinged at the tabernacles to make them easy to lower for trailering. Port Townsend, Washington, boatbuilder Kees Prins, at the helm, designed her in close consultation with the owners, Chelcie and Kathy Liu.

“Part of the reason or the impetus for this was a particularly grungy winter up here, when I thought, ‘Gee, wouldn’t it be nice to trailer a boat to a place that’s nice and warm, and sunny, and has longer days?’” Chelcie said. San Diego, maybe—but the freedom is there to venture farther afield.

They were specific with their other criteria, too. Both are, as they say, not getting any younger, so it was important that either of them, and most especially the slight-of-stature Kathy, could handle the boat alone if need be. Endurance cruising holds no appeal—“How long does it take to go from one B&B to another?” Kathy asked rhetorically—and they’re more likely to find a favorite restaurant than to cook aboard. But they wanted a workable galley. They definitely wanted a cabin heater for Northwest cruising, which can be clammy or outright sopping wet. They favored wooden construction, but wanted contemporary techniques so maintenance would be minimal. They insisted on electric auxiliary power—“that was non-negotiable,” they said, partly because they don’t care for pull-starting gasoline engines. But for safety, they didn’t want to have to lean out over the transom to deal with the motor in any way. They also wanted all sail controls led to the cockpit. One more thing: no through-hull fittings.

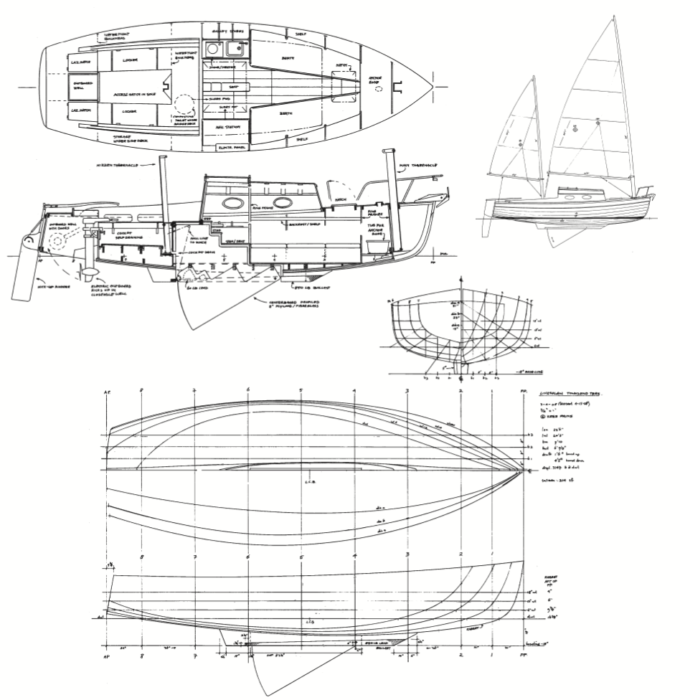

To simplify the sail plan, Prins incorporated a cat-ketch rig from a Bruce Kirby–designed Norwalk Islands Sharpie, which has free-standing carbon-fiber masts hinged in aluminum tabernacles for light weight, ease of setting up and folding down for trailering, and simplicity of rig. Its 214 sq ft of sail area also was the right size for their targeted hull length. Prins laid out a glued-lapstrake hull of 23′ 6″ LOA with a beam of 7′ 10″, comfortably within legal trailering limits. He specified using a laminated keel and 1⁄2″ okoume plywood for the bottom planking. To save weight, only the garboards are fiberglass-sheathed; the first two broadstrakes are coated with a mixture of epoxy and graphite, the rest are simply epoxy-coated, as is the interior. The bulkheads, which are set up for egg-crate-style structural support, are also made of 1⁄2″ okoume plywood, as is the deck. The well-rounded cabintop is made of two layers of 1⁄4″ plywood. No fastenings were used in the hull.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonSitting on the lowest of the centerboard steps, Chelcie Liu shows the convenience of the navigation station. The main saloon has ample sitting headroom throughout. The electronics are simple: The couple chose portable GPS and VHF units, thinking that they would be easiest to upgrade later. A house battery powers everything except the electric outboard.

In any centerboard boat, the placement and profile of the centerboard trunk has a controlling influence over the cabin layout. Prins made this centerboard’s top edge stepped in a zigzag pattern, allowing the centerboard trunk to cleverly double as companionway steps. The lowest of these is longer than the others and serves as a seat while working at the stove to port or the navigation table to starboard. The trunk also has a screw-in hatch cover mounted high on its port side, giving easy access to the lifting line and its fitting.

The plywood centerboard itself is 2″ thick to provide good strength and bearing surface in the area where it fits into the slot. When the board is fully lowered, the apex of each step corresponds to a floor timber, distributing heeling loads to the hull. The board’s below-the-keel profile, however, is sculpted to airfoil cross-sections that are parallel to the waterline when the board is fully lowered—something that Chelcie, a retired physics professor, appreciated.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonFour AGM (absorbed glass mat) batteries—two stored on each side under the settees—power the Torqueedo Cruise 2.0 electric outboard, which is housed in a well.

The space under the bridge deck to each side of the highest part of the centerboard trunk is used to good advantage. To starboard, a composting Airhead toilet—a logical choice given the Lius’ proscription on through-hulls—is mounted on cabin-sole sliders allowing it to be pulled out for use. To port, two battery chargers and the easily accessible house battery, which powers everything not related to the electric outboard, are tucked neatly out of the living space.

The cabin has excellent sitting headroom that is little impeded by the centerboard trunk. The after ends of the bunks provide comfortable vis-à-vis seating. When it’s time to hit the sack, the floorboards lift in sections that fit between the V of the berths to provide a large sleeping platform. The interior doesn’t feel cramped, has lots of stowage, and gets lots of light from six portlights and a polycarbonate foredeck hatch.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonTo port is a simple galley, with a stove that converts easily from a one-burner cookstove to a fan-powered cabin heater—a comfort on a rainy Pacific Northwest day. Visible under the bridge deck are battery chargers and the house battery; in a similar space on the starboard side of the centerboard trunk, a composting toilet is stored, ready to slide out on tracks built into the cabin sole when needed.

Some interior choices were easy to make. The galley stove is a Wallas, a dual-purpose Finnish unit that runs on kerosene and has a plastic fuel container that can easily be refilled off the boat. The stovetop has a hinged cover that swings up to expose a single burner suitable for one-pot cooking. When the top is closed, a fan kicks in to blow heat into the cabin. Electronic systems are minimal, and the GPS, VHS, and anemometer are all handheld, avoiding cabin and masthead wiring. Electronics have a habit of going obsolete rather quickly these days, and handhelds don’t pose the same problem of reinstallation posed by built-in devices. Cabin lights are battery-powered LEDs that can be placed anywhere, avoiding fixed wiring. The running lights, too, are Danish-made Lopolight LEDs, battery-powered to avoid wiring.

Other judgments, however, became a true collaboration between designer and client. For example, the Lius printed off ellipses they could tape to the cabin sides to help decide portlight sizes and shapes, ultimately choosing to diminish the forwardmost one on each side to accentuate the slope of the cabin sides. During a trunk cabin mockup, they agreed to reduce its height to better suit the hull without losing interior comfort.

To power the Torqueedo Cruise 2.0 electric outboard, four Lifeline GPL-6CT deep-cycle marine batteries in series are placed under the berths, two on each side, for a total weight of 280 lbs, rechargeable via shore-power connection. The 24-volt outboard’s thrust is equivalent to a 6-hp gasoline-powered outboard, with perhaps 30 miles of range running at slow speed. Prins feels that a gasoline-powered outboard would work as well in the boat and may provide greater thrust when needed.

The motor is placed in a conventional after out- board well. The well closes off in a manner anything but conventional, however, to reduce drag, the bane of outboard wells in sailing boats. The keyhole-shaped opening in the bottom planking, straight-sided forward for shaft clearance and rounded aft for propeller passage, can be closed off entirely. Two box-shaped plugs can be snapped into place in the shaft alley, and the oval propeller aperture is closed off by clamshell doors operated by lines from the cockpit. When everything’s closed up, the well isn’t waterproof (and doesn’t need to be), but the fair shape of the hull is restored to assure the best possible sailing performance.

The rig is simple to set up and use. Even reefing lines are led to locking cleats on the after edge of the cabintop. The mainsheet doesn’t have a traveler; instead it passes through a block and then through a hole in the mizzenmast tabernacle, then to a cam cleat. A winch mounted on the mizzenmast can be used for either the centerboard pennant or the mizzen halyard, which can be cleated off after being snubbed up. The boat has no standing rigging, and all of the running rigging is within easy reach of the helmsman when singlehanding.

Sailing couldn’t be easier. The mizzen halyard runs alongside the mast and cleats at the tabernacle. The main halyard is led to a locking cleat on the aft edge of the cabintop. When tacking, really nothing needs to be done except to haul or ease the sheets to trim the sails as needed for the new course. Jibing is equally simple, except of course that the sheets have to be hauled quickly and then eased steadily to bring the sails to the other side for the new tack—but because there’s no jib to haul around the mainmast, jibing couldn’t be easier. Visibility is excellent. The boat is well-balanced and responds quickly to the tiller. She tracks well, even in the swirling ebb current off Port Townsend.

In a light breeze off Port Townsend during the annual festival, the Tern stayed even with one racing Thunderbird sloop and bested another through a long tack to windward, which is no mean feat and bodes well for her performance. The boat isn’t meant to be a racer, but she won’t make you late for that restaurant dinner, either.

More than anything else, it’s easy to imagine set- ting out for a long cruise in interesting territory in the Townsend Tern. The ability to handle a simple rig and reduce sail jointly brings the promise of safety and security when, as is inevitable, the sailors are caught out in a blow. Fair weather or foul, approaching an anchorage with the prospect of a roomy cockpit, a commodious and warm cabin, a comfortable berth, a good book, and a hot meal—well, what else in the world does a person need?![]()

Comfortable accommodations, ample storage, a practical rig adapted wholesale from the Norwalk Islands Sharpie, and numerous clever solutions make the Townsend Tern an excellent cruising boat for a couple. The stepped centerboard allows the trunk to double as companionway steps, the lowest and longest of which allows the comfort of sitting to work in the galley or at the navigation station. The forward hatch admits light and also allows a crewman to handle most of the foredeck work, even setting and retreiving the anchor, from inside. The electric outboard motor kicks up in a well, which has doors that close to leave the hull fair for sailing. She also has a stowable composting toilet. Even with all this, the hull is well proportioned and attractive.

What an amazing collaboration and clever use of space and simplicity! I want one!! Hats off to Chelcie and Kathy. When you live long enough to know exactly what you want….!

What a throughly well thought out boat. Kees and the Lius have done a superb job of packing so much in and with real consideration to the owner’s needs in their later years.

This is perhaps nowhere better exemplified than the centerboard housing which doubles as a companionway ladder, indeed triples as a seating area for cooking etc. I love the jogged centerboard design, I don’t think I have seen its like before.

A lovely small ship.

What a lovely looking boat. If her rig had been a gaff sloop, she would look to be a twin from my more youthful years. Neighbors had a small boat of similar looks to this, unfortunately they lost interest and let it rot on the trailer. I have been looking for something similar ever since.

The Rose-coloured glass of youth strike once more!

The designer of the Norwalk Island Sharpies was Bruce Kirby (of Laser fame), not Bruce King.

Thanks for catching that, George.

The hull reminds me a lot of the Welsford Penguin I just. Bought. That rig would sure be easier to deal with trailering though.

Beautiful cruiser, but for the aft mast right in front of the companionway.